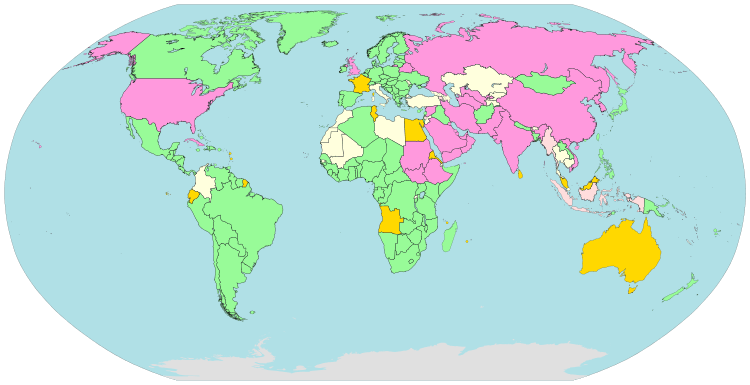

Internet censorship and surveillance by country

This list of Internet censorship and surveillance by country provides information on the types and levels of Internet censorship and surveillance that is occurring in countries around the world.

Classifications

Detailed country by country information on Internet censorship and surveillance is provided in the Freedom on the Net reports from Freedom House, by the OpenNet Initiative, by Reporters Without Borders, and in the Country Reports on Human Rights Practices from the U.S. State Department Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. The ratings produced by several of these organizations are summarized below as well as in the Censorship by country article.

Freedom on the Net reports

Freedom House has produced five editions of its report Freedom on the Net. The first in 2009 surveyed 15 countries,[5] the second in 2011 surveyed 37 countries,[6] the third in 2012 surveyed 47 countries,[7] the fourth in 2013 surveyed 60 countries,[8] and the fifth in 2014 and sixth in 2015 each surveyed 65 countries.[9][10]

Freedom on the Net provides analytical reports and numerical ratings regarding the state of Internet freedom for countries worldwide.[9] The reports are based on surveys that ask a set of questions designed to measure each country’s level of Internet and digital media freedom, as well as the access and openness of other digital means of transmitting information, particularly mobile phones and text messaging services. Results are presented for three areas:

- Obstacles to Access: infrastructural and economic barriers to access; governmental efforts to block specific applications or technologies; legal and ownership control over internet and mobile phone access providers.

- Limits on Content: filtering and blocking of websites; other forms of censorship and self-censorship; manipulation of content; the diversity of online news media; and usage of digital media for social and political activism.

- Violations of User Rights: legal protections and restrictions on online activity; surveillance and limits on privacy; and repercussions for online activity, such as legal prosecution, imprisonment, physical attacks, or other forms of harassment.

The results from the three areas are combined into a total score for a country (from 0 for best to 100 for worst) and countries are rated as "free" (0 to 30), "partly free" (31 to 60), or "not free" (61 to 100) based on the totals.

Freedom on the Net Survey Results 2009[5] 2011[6] 2012[7] 2013[8] 2014[9] 2015[10] Countries 15 37 47 60 65 65 Free 4 (27%) 8 (22%) 14 (30%) 17 (29%) 19 (29%) 18 (28%) Partly free 7 (47%) 18 (49%) 20 (43%) 29 (48%) 31 (48%) 28 (43%) Not free 4 (27%) 11 (30%) 13 (28%) 14 (23%) 15 (23%) 19 (29%) Improved n/a 5 (33%) 11 (31%) 12 (26%) 12 (18%) 15 (23%) Declined n/a 9 (60%) 17 (47%) 28 (60%) 36 (55%) 32 (49%) No change n/a 1 (7%) 8 (22%) 7 (15%) 17 (26%) 18 (28%)

In addition the 2012 report identified seven countries that were at particular risk of suffering setbacks related to Internet freedom in late 2012 and in 2013: Azerbaijan, Libya, Malaysia, Pakistan, Rwanda, Russia, and Sri Lanka. At the time the Internet in most of these countries was a relatively open and unconstrained space for free expression, but the countries also typically featured a repressive environment for traditional media and had recently considered or introduced legislation that would negatively affect Internet freedom.[7]

OpenNet Initiative

In a series of reports issued between 2007 and 2013 the OpenNet Initiative (ONI) classified the magnitude of censorship or filtering occurring in a country in four areas of activity.[11]

The magnitude or level of censorship was classified as follows:

- Pervasive: A large portion of content in several categories is blocked.

- Substantial: A number of categories are subject to a medium level of filtering or many categories are subject to a low level of filtering.

- Selective: A small number of specific sites are blocked or filtering targets a small number of categories or issues.

- Suspected: It is suspected, but not confirmed, that Web sites are being blocked.

- No evidence: No evidence of blocked Web sites, although other forms of controls may exist.

The classifications were done for the following areas of activity:

- Political: Views and information in opposition to those of the current government or related to human rights, freedom of expression, minority rights, and religious movements.

- Social: Views and information perceived as offensive or as socially sensitive, often related to sexuality, gambling, or illegal drugs and alcohol.

- Conflict/security: Views and information related to armed conflicts, border disputes, separatist movements, and militant groups.

- Internet tools: e-mail, Internet hosting, search, translation, and Voice-over Internet Protocol (VoIP) services, and censorship or filtering circumvention methods.

Due to legal concerns the OpenNet Initiative does not check for filtering of child pornography and because their classifications focus on technical filtering, they do not include other types of censorship.

Through 2010 the OpenNet Initiative had documented Internet filtering by governments in over forty countries worldwide.[12] The level of filtering was classified in 26 countries in 2007 and in 25 countries in 2009. Of the 41 separate countries classified in these two years, seven were found to show no evidence of filtering (Egypt, France, Germany, India, Ukraine, the United Kingdom, and the United States), while one was found to engage in pervasive filtering in all areas (China), 13 were found to engage in pervasive filtering in one or more areas, and 34 were found to engage in some level of filtering in one or more areas. Of the 10 countries classified in both 2007 and 2009, one reduced its level of filtering (Pakistan), five increased their level of filtering (Azerbaijan, Belarus, Kazakhstan, South Korea, and Uzbekistan), and four maintained the same level of filtering (China, Iran, Myanmar, and Tajikistan).[13]

In December 2014 ONI announced that:[14]

- After a decade of collaboration in the study and documentation of Internet filtering and control mechanisms around the world, the OpenNet Initiative partners will no longer carry out research under the ONI banner. The ONI website, including all reports and data, will be maintained indefinitely to allow continued public access to their entire archive of published work and data.

ONI's summarized global Internet filtering data was last updated on 20 September 2013.

Reporters Without Borders

RWB Enemies of the Internet and Countries under Surveillance lists

In 2006, Reporters without Borders (Reporters sans frontières, RSF), a Paris-based international non-governmental organization that advocates freedom of the press, started publishing a list of "Enemies of the Internet".[15] The organization classifies a country as an enemy of the internet because "all of these countries mark themselves out not just for their capacity to censor news and information online but also for their almost systematic repression of Internet users."[16] In 2007 a second list of countries "Under Surveillance" (originally "Under Watch") was added.[17]

|

Current Enemies of the Internet:[3][2]

Past Enemies of the Internet: |

Current Countries Under Surveillance:[3]

Past Countries Under Surveillance:

|

When the "Enemies of the Internet" list was introduced in 2006, it listed 13 countries. From 2006 to 2012 the number of countries listed fell to 10 and then rose to 12. The list was not updated in 2013. In 2014 the list grew to 19 with an increased emphasis on surveillance in addition to censorship. The list was not updated in 2015.

When the "Countries under surveillance" list was introduced in 2008, it listed 10 countries. Between 2008 and 2012 the number of countries listed grew to 16 and then fell to 11. The list was not updated in 2013, 2014, or 2015.

RWB Special report on Internet Surveillance

On 12 March 2013 Reporters Without Borders published a Special report on Internet Surveillance.[18] The report includes two new lists:

- a list of "State Enemies of the Internet", countries whose governments are involved in active, intrusive surveillance of news providers, resulting in grave violations of freedom of information and human rights; and

- a list of "Corporate Enemies of the Internet", companies that sell products that are liable to be used by governments to violate human rights and freedom of information.

The five "State Enemies of the Internet" named in March 2013 are: Bahrain, China, Iran, Syria, and Vietnam.[18]

The five "Corporate Enemies of the Internet" named in March 2013 are: Amesys (France), Blue Coat Systems (U.S.), Gamma (UK and Germany), Hacking Team (Italy), and Trovicor (Germany).[18]

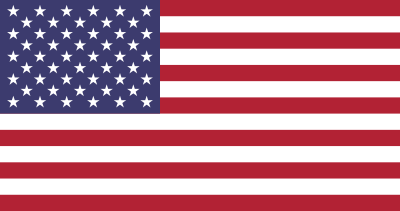

Country Reports on Human Rights Practices

Country Reports on Human Rights Practices is an annual series of reports on human rights conditions in countries throughout the world. Among other topics the reports include information on freedom of speech and the press including Internet freedom; freedom of assembly and association; and arbitrary interference with privacy, family, home, or correspondence.[19]

The reports are prepared by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor within the United States Department of State. The reports cover internationally recognized individual, civil, political, and worker rights, as set forth in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The first report was issued in 1977 covering the year 1976.[20]

Alphabetical index to classifications

Country classifications

| Part of a series on |

| Mass surveillance |

|---|

| By location |

The level of Internet censorship and surveillance in a country is classified in one of the four categories: pervasive, substantial, selective, and little or no censorship or surveillance. The classifications are based on the classifications and ratings from the Freedom on the Net reports by Freedom House supplemented with information from the OpenNet Initiative (ONI), Reporters Without Borders (RWB), and the Country Reports on Human Rights Practices by the U.S. State Department Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor.

Pervasive censorship or surveillance

A country is classified as engaged in pervasive censorship or surveillance when it often censors political, social, and other content, is engaged in mass surveillance of the Internet, and retaliates against citizens who circumvent censorship or surveillance with imprisonment or other sanctions. A country is included in the "pervasive" category when it:

- is rated as "not free" with a total score of 71 to 100 in the Freedom on the Net (FOTN) report from Freedom House,

- is rated "not free" in FOTN or is not rated in FOTN and

- is included on the "Internet enemies" list from Reporters Without Borders,[15] or

- when the OpenNet Initiative categorizes the level of Internet filtering as pervasive in any of the four areas (political, social, conflict/security, and Internet tools) for which they test.

Bahrain

Bahrain

- Rated "not free" by Freedom House in Freedom on the Net in 2011 (score 62), 2012 (score 71), 2013 (score 72), 2014 (score 74), and 2015 (score 72).[21][22][23][24][25]

- Listed as pervasive in the political and social areas, as substantial in Internet tools, and as selective in conflict/security by ONI in August 2009.[11]

- Listed as an Enemy of the Internet by RWB in 2012.[3]

- Listed as a State Enemy of the Internet by RWB in 2013 for involvement in active, intrusive surveillance of news providers, resulting in grave violations of freedom of information and human rights.[18]

Bahrain enforces an effective news blackout using an array of repressive measures, including keeping the international media away, harassing human rights activists, arresting bloggers and other online activists (one of whom died in detention), prosecuting free speech activists, and disrupting communications, especially during major demonstrations.[3]

On 5 January 2009 the Ministry of Culture and Information issued an order (Resolution No 1 of 2009)[26] pursuant to the Telecommunications Law and Press and Publications Law of Bahrain that regulates the blocking and unblocking of websites. This resolution requires all ISPs – among other things – to procure and install a website blocking software solution chosen by the Ministry. The Telecommunications Regulatory Authority ("TRA") assisted the Ministry of Culture and Information in the execution of the said Resolution by coordinating the procurement of the unified website blocking software solution. This software solution is operated solely by the Ministry of Information and Culture and neither the TRA nor ISPs have any control over sites that are blocked or unblocked.

Belarus

Belarus

- Rated "not free" by Freedom House in Freedom on the Net in 2011 (score 69), 2012 (score 69), 2013 (score 67), 2014 (score 62), and 2015 (score 64).[27][28][29][30][31]

- Listed as selective in the political, social, conflict/security and Internet tools areas by ONI in November 2010.[11]

- Listed as an Internet enemy by RWB in 2012.[3]

The Internet in Belarus, as a space used for circulating information and mobilizing protests, has been hard hit as the authorities increased the list of blocked websites and partially blocked the Internet during protests. As a way to limit coverage of demonstrations some Internet users and bloggers have been arrested and others have been invited to “preventive conversations” with the police. Law No. 317-3, which took effect on 6 January 2012, reinforced Internet surveillance and control measures.[3]

The Belarus government has moved to second- and third-generation controls to manage its national information space. Control over the Internet is centralized with the government-owned Beltelecom managing the country’s Internet gateway. Regulation is heavy with strong state involvement in the telecommunications and media market. Most users who post online media practice a degree of self-censorship prompted by fears of regulatory prosecution. The president has established a strong and elaborate information security policy and has declared his intention to exercise strict control over the Internet under the pretext of national security. The political climate is repressive and opposition leaders and independent journalists are frequently detained and prosecuted.[32]

China

China

- Rated "not free" in Freedom on the Net by Freedom House in 2009 (score 79), 2011 (score 83), 2012 (score 85), 2013 (score 86), 2014 (score 87), and 2015 (score 88).[33][34][35][36][37][38]

- Listed as pervasive in the political and conflict/security areas and as substantial in social and Internet tools by ONI in June 2009 and August 2012.[11]

- Listed as an Enemy of the Internet by RWB since 2008.[3]

- Listed as a State Enemy of the Internet by RWB in 2013 for involvement in active, intrusive surveillance of news providers, resulting in grave violations of freedom of information and human rights.[18]

Internet censorship in China is among the most stringent in the world. The government blocks Web sites that discuss Tibetan independence and the Dalai Lama, Taiwan independence, police brutality, the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989, freedom of speech, pornography, some international news sources and propaganda outlets (such as the VOA), certain religious movements (such as Falun Gong), and many blogging websites.[39] At the end of 2007 51 cyber dissidents were reportedly imprisoned in China for their online postings.[40] According to Human Rights Watch, in China the government also continues to violate domestic and international legal guarantees of freedom of press and expression by restricting bloggers, journalists, and an estimated more than 500 million Internet users. The government requires Internet search firms and state media to censor issues deemed officially “sensitive", and blocks access to foreign websites including Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube. However, the rise of Chinese online social networks—in particularly Sina’s Weibo, which has 200 million users—has created a new platform for citizens to express opinions and to challenge official limitations on freedom of speech despite intense scrutiny by China’s censors.[41]

Cuba

Cuba

- Rated "not free" in Freedom on the Net by Freedom House in 2009 (score 88), 2011 (score 87), 2012 (score 86), 2013 (score 86), 2014 (score 84), and 2015 (score 81).[42][43][44][45][46][47]

- Listed as an Internet enemy by RWB in 2011.[3]

- Not categorized by ONI due to lack of data.

Cuba has the lowest ratio of computers per inhabitant in Latin America, and the lowest internet access ratio of all the Western hemisphere.[48] Citizens have to use government controlled "access points", where their activity is monitored through IP blocking, keyword filtering and browsing history checking. The government cites its citizens' access to internet services are limited due to high costs and the American embargo, but there are reports concerning the will of the government to control access to uncensored information both from and to the outer world.[49] The Cuban government continues to imprison independent journalists for contributing reports through the Internet to web sites outside of Cuba.[50]

Even with the lack of precise figures due to the secretive nature of the regime, testimonials from independent bloggers, activists, and international watchers support the view that it is difficult for most people to access the web and that harsh punishments for individuals that do not follow government policies are the norm.[51][52] The Committee to Protect Journalists has pointed to Cuba as one of the ten most censored countries around the world.[53]

Ethiopia

Ethiopia

- Rated "not free" in Freedom on the Net by Freedom House in 2011 (score 69), 2012 (score 75), 2013 (score 79), 2014 (score 80), and 2015 (score 82).[54][55][56][57][58]

- Listed as pervasive in the political, as no evidence in social, and selective in the conflict/security and Internet tools areas by ONI in October 2012.[1]

Ethiopia remains a highly restrictive environment in which to express political dissent online. The government of Ethiopia has long filtered critical and oppositional political content. Anti-terrorism legislation is frequently used to target online speech, including in the recent conviction of a dozen individuals, many of whom were tried based on their online writings. OpenNet Initiative (ONI) testing conducted in Ethiopia in September 2012 found that online political and news content continues to be blocked, including the blogs and websites of a number of recently convicted individuals.[59]

Ethiopia has implemented a largely political filtering regime that blocks access to popular blogs and the Web sites of many news organizations, dissident political parties, and human rights groups. However, much of the media content that the government is attempting to censor can be found on sites that are not banned. The authors of the blocked blogs have in many cases continued to write for an international audience, apparently without sanction. However, Ethiopia is increasingly jailing journalists, and the government has shown a growing propensity toward repressive behavior both off- and online. Censorship is likely to become more extensive as Internet access expands across the country.[60]

Iran

Iran

- Rated "not free" in the Freedom on the Net report from Freedom House in 2009 (76 score), 2011 (89 score), 2012 (90 score), 2013 (91 score), 2014 (89 score), and 2015 (87 score).[61][62][63][64][65][66]

- Listed as pervasive in the political, social, and Internet tools areas and as substantial in conflict/security by ONI in June 2009.[11]

- Listed as an Enemy of the Internet by RWB in 2011.[3]

- Listed as a State Enemy of the Internet by RWB in 2013 for involvement in active, intrusive surveillance of news providers, resulting in grave violations of freedom of information and human rights.[18]

The Islamic Republic of Iran continues to expand and consolidate its technical filtering system, which is among the most extensive in the world. A centralized system for Internet filtering has been implemented that augments the filtering conducted at the Internet service provider (ISP) level.[67] Filtering targets content critical of the government, religion, pornographic websites, political blogs, and women's rights websites, weblogs, and online magazines.[68][69] Bloggers in Iran have been imprisoned for their Internet activities.[70] The Iranian government temporarily blocked access, between 12 May 2006 and January 2009, to video-upload sites such as YouTube.com.[71] Flickr, which was blocked for almost the same amount of time was opened in February 2009. But after 2009 election protests YouTube, Flickr, Twitter, Facebook and many more websites were blocked indefinitely.[72]

Kuwait

Kuwait

- Listed as pervasive in the social and Internet tools areas and as selective in political and conflict/security by ONI in June 2009.[11]

The primary target of Internet filtering is pornography and, to a lesser extent, gay and lesbian content.[73] The Kuwait Ministry of Communication regulates ISPs, making them block pornographic, anti-religion, anti-tradition, and anti-security websites.[74] Both private ISPs and the government take actions to filter the Internet.[75][76]

The Kuwait Institute for Scientific Research (KISR) operates the Domain Name System in Kuwait and does not register domain names which are "injurious to public order or to public sensibilities or otherwise do not comply with the laws of Kuwait".[77] VoIP is legal in Kuwait, and Zain, one of the mobile operators, started testing VoLTE in Kuwait.[78]

North Korea

North Korea

North Korea is cut off from the Internet, much as it is from other areas with respect to the world. Only a few hundred thousand citizens in North Korea, representing about 4% of the total population, have access to the Internet, which is heavily censored by the national government.[80] According to the RWB, North Korea is a prime example where all mediums of communication are controlled by the government. According to the RWB, the Internet is used by the North Korean government primarily to spread propaganda. The North Korean network is monitored heavily. All websites are under government control, as is all other media in North Korea.[81]

Oman

Oman

- Listed as pervasive in the social area, as substantial in Internet tools, selective in political, and as no evidence in conflict/security by ONI in August 2009.[11]

Oman engages in extensive filtering of pornographic Web sites, gay and lesbian content, content that is critical of Islam, content about illegal drugs, and anonymizer sites used to circumvent blocking. There is no evidence of technical filtering of political content, but laws and regulations restrict free expression online and encourage self-censorship.[82]

Qatar

Qatar

- Listed as pervasive in the social and Internet tools areas and selective in political and conflict/security by ONI in August 2009.[11]

Qatar is the second most connected country in the Arab region, but Internet users have heavily censored access to the Internet. Qatar filters pornography, political criticism of Gulf countries, gay and lesbian content, sexual health resources, dating and escort services, and privacy and circumvention tools. Political filtering is highly selective, but journalists self-censor on sensitive issues such as government policies, Islam, and the ruling family.[83]

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia

- Rated "not free" by Freedom House in Freedom on the Net in 2011 (score 70), 2012 (score 71), 2013 (score 70), 2014 (score 72), and 2015 (score 73).[84][85][86][87][88]

- Listed as pervasive in the social and Internet tools areas, as substantial in political, and as selective in conflict/security by ONI in August 2009.[11]

- Listed as an Internet enemy by RWB in 2011.[3]

Saudi Arabia directs all international Internet traffic through a proxy run by the CITC. Content filtering is implemented there using software by Secure Computing.[89] Additionally, a number of sites are blocked according to two lists maintained by the Internet Services Unit (ISU):[90] one containing "immoral" (mostly pornographic) sites, the other based on directions from a security committee run by the Ministry of Interior (including sites critical of the Saudi government). Citizens are encouraged to actively report "immoral" sites for blocking, using a provided Web form. Many Wikipedia articles in different languages have been included in the censorship of "immoral" content in Saudi Arabia. The legal basis for content-filtering is the resolution by Council of Ministers dated 12 February 2001.[91] According to a study carried out in 2004 by the OpenNet Initiative: "The most aggressive censorship focused on pornography, drug use, gambling, religious conversion of Muslims, and filtering circumvention tools."[89]

Syria

Syria

- Rated "not free" in Freedom on the Net by Freedom House in 2012 (score 83), 2013 (score 85), 2014 (score 88), and 2015 (score 87).[92][93][94][95]

- Listed as pervasive in the political and Internet tools areas, and as selective in social and conflict/security by ONI in August 2009.[11]

- Listed as an Enemy of the Internet by RWB in 2011.[3]

- Listed as a State Enemy of the Internet by RWB in 2013 for involvement in active, intrusive surveillance of news providers, resulting in grave violations of freedom of information and human rights.[18]

Syria has banned websites for political reasons and arrested people accessing them. In addition to filtering a wide range of Web content, the Syrian government monitors Internet use very closely and has detained citizens "for expressing their opinions or reporting information online." Vague and broadly worded laws invite government abuse and have prompted Internet users to engage in self-censoring and self-monitoring to avoid the state's ambiguous grounds for arrest.[68][96]

During the Syrian civil war Internet connectivity between Syria and the outside world shut down in late November 2011[97] and again in early May 2013.[98]

Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan

- Listed as pervasive in the political area and as selective in social, conflict/security, and Internet tools by ONI in December 2010.[11]

- Listed as an Internet enemy by RWB in 2011.[3]

Internet usage in Turkmenistan is under tight control of the government. Turkmen got their news through satellite television until 2008 when the government decided to get rid of satellites, leaving Internet as the only medium where information could be gathered. The Internet is monitored thoroughly by the government and websites run by human rights organizations and news agencies are blocked. Attempts to get around this censorship can lead to grave consequences.[99]

United Arab Emirates

United Arab Emirates

- Rated "not free" by Freedom House in Freedom on the Net in 2013 (score 66), 2014 (score 67), and 2015 (score 68).[100][101][102]

- Listed as pervasive in the social and Internet tools areas, as substantial in political, and as selective in conflict/security by ONI in August 2009.[11]

- Listed as Under Surveillance by RWB in 2011.[3]

The United Arab Emirates forcibly censors the Internet using Secure Computing's solution. The nation's ISPs Etisalat and du (telco) ban pornography, politically sensitive material, all Israeli domains,[103] and anything against the perceived moral values of the UAE. All or most VoIP services are blocked. The Emirates Discussion Forum (Arabic: منتدى الحوار الإماراتي), or simply uaehewar.net, has been subjected to multiple censorship actions by UAE authorities.[104]

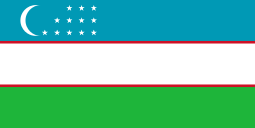

Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan

- Rated "not free" in Freedom on the Net from Freedom House in 2012 (score 77), 2013 (score 78), 2014 (score 79), and 2015 (score 78).[105][106][107][108]

- Uzbekistan has been listed as an Internet enemy by Reporters Without Borders since the list was created in 2006.[3]

- The OpenNet Initiative found evidence that Internet filtering was pervasive in the political area and selective in the social, conflict/security, and Internet tools areas during testing that was reported in 2008 and 2010.[1][11]

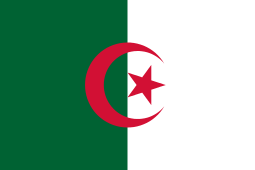

Uzbekistan maintains the most extensive and pervasive filtering system among the CIS countries. It prevents access to websites regarding banned Islamic movements, independent media, NGOs, material critical of the government's human rights violations, discussion of the events in Egypt, Tunisia, and Bahrain, and news about demonstrations and protest movements.[68] Contributors to online discussion of the events in Egypt, Tunisia, and Bahrain have been arrested.[109] Some Internet cafes in the capital have posted warnings that users will be fined for viewing pornographic websites or website containing banned political material.[110] The main VoIP protocols SIP and IAX used to be blocked for individual users; however, as of July 2010, blocks were no longer in place. Facebook was blocked for few days in 2010.[111]

Vietnam

Vietnam

- Rated "not free" by Freedom House in Freedom on the Net in 2011 (score 73), 2012 (score 73), 2013 (score 75), 2014 (score 76), and 2015 (score 76).[112][113][114][115][116]

- Classified by ONI as pervasive in the political, as substantial in the Internet tools, and as selective in the social and conflict/security areas in 2011.[1][11]

- Listed as an Enemy of the Internet by RWB in 2011.[3]

- Listed as a State Enemy of the Internet by RWB in 2013 for involvement in active, intrusive surveillance of news providers, resulting in grave violations of freedom of information and human rights.[18]

The main networks in Vietnam prevent access to websites critical of the Vietnamese government, expatriate political parties, and international human rights organizations, among others.[68] Online police reportedly monitor Internet cafes and cyber dissidents have been imprisoned for advocating democracy.[117]

Yemen

Yemen

- Listed as pervasive in the social area, as substantial in political and Internet tools, and as selective in the conflict/security area by ONI in October 2012.[1]

- Listed as Under Surveillance by RWB in 2008 and 2009, but not in 2010 or 2011.[3]

Yemen censors pornography, nudity, gay and lesbian content, escort and dating services, sites displaying provocative attire, Web sites which present critical reviews of Islam and/or attempt to convert Muslims to other religions, or content related to alcohol, gambling, and drugs.[118]

Yemen’s Ministry of Information declared in April 2008 that the penal code will be used to prosecute writers who publish Internet content that "incites hatred" or "harms national interests".[119] Yemen's two ISPs, YemenNet and TeleYemen, block access to gambling, adult, sex education, and some religious content.[68] The ISP TeleYemen (aka Y.Net) prohibits "sending any message which is offensive on moral, religious, communal, or political grounds" and will report "any use or attempted use of the Y.Net service which contravenes any applicable Law of the Republic of Yemen". TeleYemen reserves the right to control access to data stored in its system “in any manner deemed appropriate by TeleYemen.”[120]

In Yemen closed rooms or curtains that might obstruct views of the monitors are not allowed in Internet cafés, computer screens in Internet cafés must be visible to the floor supervisor, police have ordered some Internet cafés to close at midnight, and demanded that users show their identification cards to the café operator.[121]

Substantial censorship or surveillance

Countries included in this classification are engaged in substantial Internet censorship and surveillance. This includes countries where a number of categories are subject to a medium level of filtering or many categories are subject to a low level of filtering. A country is included in the "substantial" category when it:

- is not included in the "pervasive" category, and

- is rated as "not free" in the Freedom on the Net (FOTN) report from Freedom House, or

- is rated "partly free" or is not rated in FOTN, and

- is included on the "Internet enemies" list from Reporters Without Borders,[15] or

- when the OpenNet Initiative categorizes the level of Internet filtering as pervasive or substantial in any of the four areas (political, social, conflict/security, and Internet tools) for which they test.

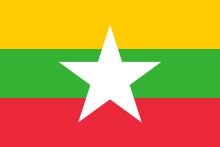

Burma

Burma

- Rated "not free" by Freedom House in Freedom on the Net in 2011 (score 88), 2012 (score 75), and 2013 (score 62), as "partly free" in 2014 (score 60), and "not free" in 2015 (score 63).[122][123][124][125][126]

- Listed as selective in the political and Internet tools areas, as substantial in social, and as no evidence of filtering in conflict/security by ONI in August 2012.[1][127]

- Listed as an Internet enemy by RWB from 2006 to 2013.[3]

Beginning in September 2012, after years spent as one of the world’s most strictly controlled information environments, the government of Burma (Myanmar) began to open up access to previously censored online content. Independent and foreign news sites, oppositional political content, and sites with content relating to human rights and political reform—all previously blocked—became accessible. In August 2012, the Burmese Press Scrutiny and Registration Department announced that all pre-publication censorship of the press was to be discontinued, such that articles dealing with religion and politics would no longer require review by the government before publication.[128]

Restrictions on content deemed harmful to state security remain in place. Pornography is still widely blocked, as is content relating to alcohol and drugs, gambling websites, online dating sites, sex education, gay and lesbian content, and web censorship circumvention tools. In 2012 almost all of the previously blocked websites of opposition political parties, critical political content, and independent news sites were accessible, with only 5 of 541 tested URLs categorized as political content blocked.[128]

Gambia

Gambia

- Rated "not free" by Freedom House in Freedom on the Net in 2014 (score 65) and 2015 (score 65).[129][130]

- Not individually classified by ONI,[11] but classified as selective based on the limited descriptions in the ONI profile for the sub-Saharan Africa region.[131]

There are no government restrictions on access to the Internet or reports that the government monitors e-mail or Internet chat rooms without appropriate legal authority. Individuals and groups can generally engage in the peaceful expression of views via the Internet, including by e-mail. However, Internet users reported they could not access the Web sites of foreign online newspapers Freedom, The Gambia Echo, Hellogambia, and Jollofnews, which criticized the government.[132]

The constitution and law provide for freedom of speech and press; however, the government restricted these rights. According to the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders, "the environment for independent and opposition media remained hostile, with numerous obstacles to freedom of expression, including administrative hurdles, arbitrary arrest and detention, intimidation and judicial harassment against journalists, and the closure of media outlets, leading to self-censorship." Individuals who publicly or privately criticized the government or the president risked government reprisal. In March 2011 President Jammeh warned independent journalists that he would “not compromise or sacrifice the peace, security, stability, dignity, and the well-being of Gambians for the sake of freedom of expression.” Accusing some journalists of being the “mouthpiece of opposition parties", he vowed to prosecute any journalist who offended him. The National Intelligence Agency (NIA) was involved in arbitrary closure of media outlets and the extrajudicial detention of journalists.[132]

In 2007 a Gambian journalist living in the US was convicted of sedition for an article published online; she was fined USD12,000;[133] in 2006 the Gambian police ordered all subscribers to an online independent newspaper to report to the police or face arrest.[134]

The constitution and law prohibit arbitrary interference with privacy, family, home, or correspondence, but the government does not respect these prohibitions. Observers believe the government monitors citizens engaged in activities that it deems objectionable.[132]

Indonesia

Indonesia

- Indonesia was rated "partly free" in Freedom on the Net in 2011 (score 46), 2012 (score 42), 2013 (score 41), 2014 (score 42), and 2015 (score 42).[135][136][137][138][139]

- Listed as substantial in the social area, as selective in the political and Internet tools areas, and as no evidence of filtering in the conflict/security area by ONI in 2011 based on testing done during 2009 and 2010. Testing also showed that Internet filtering in Indonesia is unsystematic and inconsistent, illustrated by the differences found in the level of filtering between ISPs.[140]

Although the government of Indonesia holds a positive view about the Internet as a means for economic development, it has become increasingly concerned over the effect of access to information and has demonstrated an interest in increasing its control over offensive online content, particularly pornographic and anti-Islamic online content. The government regulates such content through legal and regulatory frameworks and through partnerships with ISPs and Internet cafés.[140]

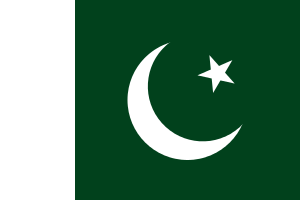

Pakistan

Pakistan

- Rated "partly free" by Freedom House in Freedom on the Net in 2011 (score 55) and as "not free" in 2012 (score 63), 2013 (score 67), 2014 (score 69), and 2015 (score 69).[141][142][143][144][145]

- Listed as substantial in the conflict/security and as selective in the political, social, and Internet tools areas by ONI in 2011.[1][11]

- Listed as an Internet Enemy by RWB in 2014.[2]

Pakistanis currently have free access to a wide range of Internet content, including most sexual, political, social, and religious sites on the Internet. Internet filtering remains both inconsistent and intermittent. Although the majority of filtering in Pakistan is intermittent—such as the occasional block on a major Web site like Blogspot or YouTube—the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) continues to block sites containing content it considers to be blasphemous, anti-Islamic, or threatening to internal security. Pakistan has blocked access to websites critical of the government.[146]

Palestinian territories

Palestinian territories

- Listed as substantial in the social area and as no evidence in political, conflict/security, and Internet tools by ONI in August 2009.[11]

Access to Internet in the Palestinian territories remains relatively open, although social filtering of sexually explicit content has been implemented in Palestine. Internet in the West Bank remains almost entirely unfiltered, save for a single news Web site that was banned for roughly six months starting in late 2008. Media freedom is constrained in Palestine and the West Bank by the political upheaval and internal conflict as well as by the Israeli forces.[147]

Russia

Russia

- Rated "partly free" by Freedom House in Freedom on the Net in 2009 (score 49), 2011 (score 52), 2012 (score 52), 2013 (score 54), and 2014 (score 60) and as "not free" in 2015 (score 62).[148][149][150][151][152][153]

- Listed as selective in the political and social areas and as no evidence in conflict/security and Internet tools by ONI in December 2010.[11]

- Listed as under surveillance by RWB from 2010 to 2013.[3]

- Listed as an Internet Enemy by RWB in 2014.[2]

- The absence of overt state-mandated Internet filtering in Russia before 2012 had led some observers to conclude that the Russian Internet represents an open and uncontested space. In fact, the Russian government actively competes in Russian cyberspace employing second- and third-generation strategies as a means to shape the national information space and promote pro-government political messages and strategies. This approach is consistent with the government’s strategic view of cyberspace that is articulated in strategies such as the doctrine of information security. The DoS attacks against Estonia (May 2007) and Georgia (August 2008) may be an indication of the government’s active interest in mobilizing and shaping activities in Russian cyberspace.[154]

In July 2012, the Russian State Duma passed the Bill 89417-6 which created a blacklist of Internet sites containing alleged child pornography, drug-related material, extremist material, and other content illegal in Russia.[155][156] The Russian Internet blacklist was officially launched in November 2012, despite criticism by major websites and NGOs.[157]

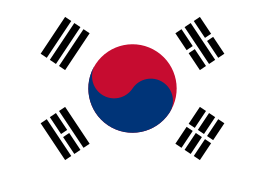

South Korea

South Korea

- Rated "partly free" in Freedom on the Net by Freedom House in 2011 (score 32), 2012 (score 34), 2013 (score 32), 2014 (score 33), and 2015 (score 34).[158][159][160][161][162]

- Listed as pervasive in the conflict/security area, as selective in social, and as no evidence in political and Internet tools by ONI in 2011.[1][11]

- Listed as Under Surveillance by RWB in 2011.[3]

South Korea is a world leader in Internet and broadband penetration, but its citizens do not have access to a free and unfiltered Internet. South Korea’s government maintains a wide-ranging approach toward the regulation of specific online content and imposes a substantial level of censorship on elections-related discourse and on a large number of Web sites that the government deems subversive or socially harmful.[163] The policies are particularly strong toward suppressing anonymity in the Korean internet.

In 2007, numerous bloggers were censored and their posts deleted by police for expressing criticism of, or even support for, presidential candidates. This even led to some bloggers being arrested by the police.[164]

South Korea uses IP address blocking to ban web sites considered sympathetic to North Korea.[68][165] Illegal websites, such as those offering unrated games, file sharing, pornography, and gambling, are also blocked. Any attempts to bypass this is enforced with the "three-strikes" program.

Sudan

Sudan

- Rated "not free" by Freedom House in Freedom on the Net in 2013 (score 63), 2014 (score 65), and 2015 (score 65).[166][167][168]

- Listed as substantial in the social and Internet tools areas and as selective in political, and as no evidence in conflict/security by ONI in August 2009.[11]

- Listed as an Internet Enemy by RWB in 2014.[2]

Sudan openly acknowledges filtering content that transgresses public morality and ethics or threatens order. The state's regulatory authority has established a special unit to monitor and implement filtration; this primarily targets pornography and, to a lesser extent, gay and lesbian content, dating sites, provocative attire, and many anonymizer and proxy Web sites.[169]

Thailand

Thailand

- Rated "not free" in Freedom on the Net by Freedom House in 2011-2012 (scores 61 and 61) and 2014-2015 (scores 62 and 63).[170][171][172][173] Freedom House listed Thailand as "partly free" in 2013 (score 60), due partially to improvements in access to the Internet.[174]

- Listed as selective in political, social, and Internet tools and as no evidence in conflict/security by ONI in 2011.[1][11]

- Listed as Under Surveillance by RWB in 2011.[3]

Prior to the September 2006 military coup d'état most Internet censorship in Thailand was focused on blocking pornographic websites. The following years have seen a constant stream of sometimes violent protests, regional unrest,[175] emergency decrees,[176] a new cybercrimes law,[177] and an updated Internal Security Act.[178] And year by year Internet censorship has grown, with its focus shifting to lèse majesté, national security, and political issues. Estimates put the number of websites blocked at over 110,000 and growing in 2010.[179]

Reasons for blocking:

Prior to

2006[180]

2010[181]

Reason11% 77% lèse majesté content (content that defames, insults, threatens, or is unflattering to the King, includes national security and some political issues) 60% 22% pornographic content 2% <1% content related to gambling 27% <1% copyright infringement, illegal products and services, illegal drugs, sales of sex equipment, prostitution, …

According to the Associated Press, the Computer Crime Act has contributed to a sharp increase in the number of lèse majesté cases tried each year in Thailand.[182] While between 1990 and 2005, roughly five cases were tried in Thai courts each year, since that time about 400 cases have come to trial—a 1,500 percent increase.[182]

Selective censorship or surveillance

Countries included in this classification were found to practice selective Internet censorship and surveillance. This includes countries where a small number of specific sites are blocked or censorship targets a small number of categories or issues. A country is included in the "selective" category when it:

- is not included in the "pervasive" or "substantial" categories, and

- is rated as "partly free" in the Freedom on the Net (FOTN) report from Freedom House, or

- is included on the "Internet enemies" list from Reporters Without Borders,[15] or

- is not rated in FOTN and the OpenNet Initiative categorizes the level of Internet filtering as selective in any of the four areas (political, social, conflict/security, and Internet tools) for which they test.

Angola

Angola

- Rated "partly free" by Freedom House in Freedom on the Net in 2013 (score 34), 2014 (score 38), and 2015 (score 39).[183][184][185]

- Angola is not individually classified by ONI[1] and does not appear on the RWB lists.[3]

There are no government restrictions on access to the Internet or credible reports that the government monitors e-mail or chat rooms without judicial oversight.[186] And aside from child pornography and copyrighted material, the government does not block or filter Internet content and there are no restrictions on the type of information that can be exchanged. Social media and communications apps such as YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, and international blog-hosting services are all freely available.[183]

Censorship of traditional news and information sources is common, leading to worries that similar efforts to control online information will eventually emerge. Defamation, libel, and insulting the country or president in "public meetings or by disseminating words, images, writings, or sound" are crimes punishable by imprisonment. A proposed "Law to Combat Crime in the Area of Information Technologies and Communication" was introduced by the National Assembly in March 2011. Often referred to as the cybercrime bill, the law was ultimately withdrawn in May 2011 as a result of international pressure and vocal objections from civil society. However, the government publicly stated that similar clauses regarding cybercrimes will be incorporated into an ongoing revision of the penal code, leaving open the possibility of Internet-specific restrictions becoming law in the future.[183]

An April 2013 news report claimed that state security services were planning to implement electronic monitoring that could track email and other digital communications.[187] In March 2014, corroborating information from military sources was found, affirming that a German company had assisted the Angolan military intelligence in installing a monitoring system at the BATOPE base around September 2013. There was also evidence of a major ISP hosting a spyware system.[184]

Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan

- Rated "partly free" by Freedom House in Freedom on the Net in 2011 (score 48), 2012 (score 50), 2013 (score 52), 2014 (score 55), and 2015 (score 56).[188][189][190][191][192]

- Listed as selective in the political and social areas and as no evidence in conflict/security and Internet tools by ONI in November 2009.[11]

The Internet in Azerbaijan remains largely free from direct censorship, although there is evidence of second- and third-generation controls.[193]

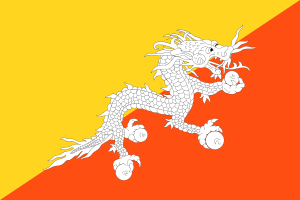

Bhutan

Bhutan

Individuals and groups are generally permitted to engage in peaceful expression of views via the Internet. Government officials state that the government does not block access, restrict content, or censor Web sites. However, Freedom House reports the government occasionally blocks access to Web sites containing pornography or information deemed offensive to the state; but that such blocked information typically does not extend to political content. In its Freedom of the Press 2012 report, Freedom House described high levels of self-censorship among media practitioners, despite few reports of official intimidation or threats.[194]

The constitution provides for freedom of speech including for members of the press, and the government generally respects these rights in practice. Citizens can publicly and privately criticize the government without reprisal. The constitution states that persons "shall not be subjected to arbitrary or unlawful interference with his or her privacy, family, home, or correspondence, nor to unlawful attacks on the person’s honor and reputation", and the government generally respects these prohibitions.[194]

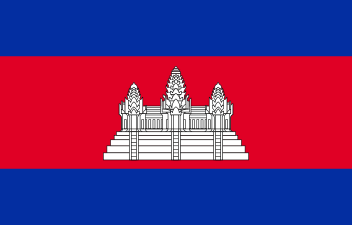

Cambodia

Cambodia

- Rated "partly free" in Freedom on the Net by Freedom House in 2013 (score 47), 2014 (score 47), and 2015 (score 48).[195][196][197]

Compared to traditional media in Cambodia, new media, including online news, social networks and personal blogs, enjoy more freedom and independence from government censorship and restrictions. However, the government does proactively block blogs and websites, either on moral grounds, or for hosting content deemed critical of the government. The government restricts access to sexually explicit content, but does not systematically censor online political discourse. Since 2011 three blogs hosted overseas have been blocked for perceived antigovernment content. In 2012, government ministries threatened to shutter internet cafes too near schools—citing moral concerns—and instituted surveillance of cafe premises and cell phone subscribers as a security measure.[198]

There are no government restrictions on access to the Internet or credible reports that the government monitors e-mail or Internet chat rooms without appropriate legal authority. During 2012 NGOs expressed concern about potential online restrictions. In February and November, the government published two circulars, which, if implemented fully, would require Internet cafes to install surveillance cameras and restrict operations within major urban centers. Activists also reported concern about a draft “cybercrimes” law, noting that it could be used to restrict online freedoms. The government maintained it would only regulate criminal activity.[199]

Ecuador

Ecuador

- Rated "partly free" in Freedom on the Net by Freedom House in 2013 (score 37), 2014 (score 37), and 2015 (score 37).[200][201][202]

- Ecuador is not individually classified by ONI[1] and does not appear on the RWB lists.[3]

There is no widespread blocking or filtering of websites in Ecuador and access to blogs and social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube is generally free and open.[203] There were no government restrictions on access to the Internet or credible reports that the government monitored e-mail or Internet chat rooms. However, on 11 July 2012 the government passed a new telecommunications regulation, requiring that Internet service providers fulfill all information requests from the superintendent of telecommunications, allowing access to client addresses and information without a judicial order.[204]

Standard defamation laws apply to content posted online. Attempts to censor statements made in times of heightened political sensitivity have been reported, as have alleged instances of censorship via the overly broad application of copyright to content critical of the government.[203]

Self-censorship of comments critical of the government is encouraged. In January 2013, for example, President Correa called for the National Secretary of Intelligence (SENAIN) to investigate two Twitter users who had published disparaging comments about him, an announcement which sent a warning to others not to post comments critical of the president. At the president’s request, two news sites La Hora and El Comercio suspended the reader comments sections of their websites. While there are no official constraints on organizing protests over the Internet, warnings from the president stating that the act of protesting will be interpreted as "an attempt to destabilize the government" have undoubtedly discouraged some from organizing and participating in protests.[203]

Ecuador’s new "Organic Law on Communications" was passed in June 2013. The law recognizes a right to communication. Media companies are required to collect and store user information. “Media lynching”, which appears to extend to any accusation of corruption or investigation of a public official—even those that are supported with evidence, is prohibited. Websites bear “ultimate responsibility” for all content they host, including content authored by third parties. The law creates a new media regulator to prohibit the dissemination of “unbalanced” information and bans non-degreed journalists from publishing, effectively outlawing much investigative reporting and citizen journalism.[203]

Egypt

Egypt

- Rated "partly free" in Freedom on the Net by Freedom House in 2009 (score 51), 2011 (score 54), 2012 (score 59), 2013 (score 60), and 2014 (score 60); and "not free" in 2015 (score 61).[205][206][207][208][209][210]

- In August 2009 ONI found no evidence of Internet filtering in any of the four areas (political, social, conflict/security, and Internet tools).[11]

- Listed as an Internet Enemy by RWB from 2006 to 2010.

- Listed as Under Surveillance by RWB from 2011 to the present.[3]

The Internet in Egypt was not directly censored under President Hosni Mubarak, but his regime kept watch on the most critical bloggers and regularly arrested them. At the height of the uprising against the dictatorship, in late January 2011, the authorities first filtered pictures of the repression and then cut off Internet access entirely in a bid to stop the revolt spreading. The success of the 2011 Egyptian revolution offers a chance to establish greater freedom of expression in Egypt, especially online. In response to these dramatic events and opportunities, in March 2011, Reporters Without Borders moved Egypt from its "Internet enemies" list to its list of countries "under surveillance".[211]

In March 2012 Reporters Without Borders reported:[212]

The first anniversary of Egypt’s revolution was celebrated in a climate of uncertainty and tension between a contested military power, a protest movement attempting to get its second wind, and triumphant Islamists. Bloggers and netizens critical of the army have been harassed, threatened, and sometimes arrested.

The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF), which has been leading the country since February 2011, has not only perpetuated Hosni Mubarak’s ways of controlling information, but has strengthened them.

Eritrea

Eritrea

- Listed as Under Surveillance by RWB in 2008, 2009, and again from 2011 to the present.[3]

Eritrea has not set up a widespread automatic Internet filtering system, but it does not hesitate to order blocking of several diaspora websites critical of the regime. Access to these sites is blocked by two of the Internet service providers, Erson and Ewan, as are pornographic websites and YouTube. Self-censorship is said to be widespread.[213]

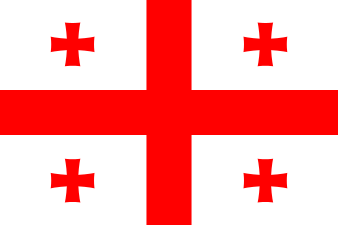

Georgia

Georgia

- Rated "partly free" by Freedom House in Freedom on the Net in 2009 (score 43) and 2011 (score 35) and "free" in 2012 (score 30), 2013 (score 26), 2014 (score 26), and 2015 (score 24).[214][215][216][217][218][219]

- Listed as selective in the political and conflict/security areas and as no evidence in social and Internet tools by ONI in November 2010.[11]

Access to Internet content in Georgia is largely unrestricted as the legal constitutional framework, developed after the 2003 Rose Revolution, established a series of provisions that should, in theory, curtail any attempts by the state to censor the Internet. At the same time, these legal instruments have not been sufficient to prevent limited filtering on corporate and educational networks. Georgia’s dependence on international connectivity makes it vulnerable to upstream filtering, evident in the March 2008 blocking of YouTube by Turk Telecom.[220]

Georgia blocked all websites with addresses ending in .ru (top-level domain for Russian Federation) during the Russo-Georgian War in 2008.[221]

India

India

- Rated "partly free" in Freedom on the Net by Freedom House in 2009 (score 34), 2011 (score 36), 2012 (score 39), 2013 (score 47), 2014 (score 42), and 2015 (score 40).[222][223][224][225][226][227]

- Listed as selective in all areas by ONI in 2011.[4][228]

- Listed as Under Surveillance by RWB in 2012 and 2013 and as an Internet Enemy in 2014.[2][3]

Since the Mumbai bombings of 2008, the Indian authorities have stepped up Internet surveillance and pressure on technical service providers, while publicly rejecting accusations of censorship.[3]

ONI describes India as:[228]

- A stable democracy with a strong tradition of press freedom, [that] nevertheless continues its regime of Internet filtering. However, India’s selective censorship of blogs and other content, often under the guise of security, has also been met with significant opposition.

- Indian ISPs continue to selectively filter Web sites identified by authorities. However, government attempts at filtering have not been entirely effective because blocked content has quickly migrated to other Web sites and users have found ways to circumvent filtering. The government has also been criticized for a poor understanding of the technical feasibility of censorship and for haphazardly choosing which Web sites to block.

Jordan

Jordan

- Rated "partly free" by Freedom House in Freedom on the Net in 2011 (score 42), 2012 (score 45), 2013 (score 46), 2014 (score 48), and 2015 (score 50).[229][230][231][232][233]

- Listed as selective in the political area and as no evidence in social, conflict/security, and Internet tools by ONI in August 2009.[11]

Censorship in Jordan is relatively light, with filtering selectively applied to only a small number of sites. However, media laws and regulations encourage some measure of self-censorship in cyberspace, and citizens have reportedly been questioned and arrested for Web content they have authored. Censorship in Jordan is mainly focused on political issues that might be seen as a threat to national security due to the nation's close proximity to regional hotspots like Israel, Iraq, Lebanon, and the Palestinian territories.[234]

In 2013 the Press and Publications Department initiated a ban on Jordanian news websites which had not registered and been licensed by government agency. The order issued to Telecommunication Regulatory Commission contained a list of over 300 websites to be blocked. The new law, which enforced registration of websites, would also hold online news sites accountable for the comments left by their readers. They would also be required to archive all comments for at least six months.[235]

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan

- Rated "partly free" by Freedom House in Freedom on the Net in 2011 (score 55), 2012 (score 58), 2013 (score 59), 2014 (score 48), and 2015 (score 61).[236][237][238][239][240]

- Listed as selective in the political and social areas and as no evidence in conflict/security and Internet tools by ONI in December 2010.[11]

- Listed as Under Surveillance by RWB in 2012.[3]

In 2011 the government responded to an oil worker's strike, a major riot, a wave of bombings, and the president’s ailing health by imposing new, repressive Internet regulations, greater control of information, especially online information, blocking of news websites, and cutting communications with the city of Zhanaozen during the riot.[3]

Kazakhstan uses its significant regulatory authority to ensure that all Internet traffic passes through infrastructure controlled by the dominant telecommunications provider KazakhTelecom. Selective content filtering is widely used, and second- and third-generation control strategies are evident. Independent media and bloggers reportedly practice self-censorship for fear of government reprisal. The technical sophistication of the Kazakhstan Internet environment is evolving and the government’s tendency toward stricter online controls warrant closer examination and monitoring.[241]

Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan

- Rated "partly free" by Freedom House in Freedom on the Net 2012 (score 35), 2013 (score 35), 2014 (score 34), and 2015 (score 35).[242][243][244][245]

- Listed as selective in the political and social areas and as no evidence in conflict/security and Internet tools by ONI in December 2010.[11]

Access to the Internet in Kyrgyzstan has deteriorated as heightened political tensions have led to more frequent instances of second- and third-generation controls. The government has become more sensitive to the Internet’s influence on domestic politics and enacted laws that increase its authority to regulate the sector.[246]

Liberalization of the telecommunications market in Kyrgyzstan has made the Internet affordable for the majority of the population. However, Kyrgyzstan is an effectively cyberlocked country dependent on purchasing bandwidth from Kazakhstan and Russia. The increasingly authoritarian regime in Kazakhstan is shifting toward more restrictive Internet controls, which is leading to instances of ‘‘upstream filtering’’ affecting ISPs in Kyrgyzstan.[246]

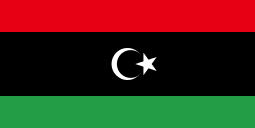

Libya

Libya

- Rated "partly free" in Freedom on the Net by Freedom House in 2012 (score 43), 2013 (score 45), 2014 (score 48), and 2015 (score 54).[247][248][249][250]

- Listed as selective in the political area and as no evidence in social, conflict/security, and Internet tools by ONI in August 2009.[11]

- Identified by Freedom House as one of seven countries seen as particularly vulnerable to deterioration in their online freedoms during 2012 and 2013.[251]

The overthrow of the Gaddafi regime in August 2011 ended an era of censorship. The Constitutional Declaration under the interim governments provides for freedom of opinion, expression, and the press. There are no government restrictions on access to the Internet, but there are credible reports that the government monitors e-mail or Internet communication. Social media applications, such as YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter, were freely accessible. Internet content is not filtered, but service is often unreliable or nonexistent outside major cities.[252]

Before his removal and death, Col. Gaddafi had tried to impose a news blackout by cutting access to the Internet.[3] Prior to this, Internet filtering under the Gaddafi regime had become more selective, focusing on a few political opposition Web sites. This relatively lenient filtering policy coincided with what was arguably a trend toward greater openness and increasing freedom of the press. However, the legal and political climate continued to encourage self-censorship in online media.[253]

In 2006 Reporters Without Borders removed Libya from their list of Internet enemies after a fact-finding visit found no evidence of Internet censorship.[15] ONI’s 2007–2008 technical test results contradicted that conclusion, however.[253] And in 2012 RWB removed Libya from its list of countries under surveillance.[3]

Mali

Mali

There are no government restrictions on access to the Internet except for pornography or material deemed objectionable to Islamic values. There were no credible reports that the government monitored e-mail or Internet chat rooms without judicial oversight. Individuals and groups engage in the expression of views via the Internet, including by e‑mail.[254]

The Ministry of Islamic Affairs continues to block Web sites considered anti-Islamic or pornographic. In November 2011 the Telecommunications Authority blocked and banned a local blog, Hilath.com, at the request of the Islamic Ministry because of its anti-Islamic content. The blog was known for promoting religious tolerance, as well as for discussing the blogger’s homosexuality. NGO sources stated that in general the media practiced self-censorship on issues related to Islam due to fears of being labeled "anti-Islamic" and subsequently harassed. This self-censorship also applied to reporting on problems in and criticisms of the judiciary.[254]

Mauritania

Mauritania

- Classified by ONI as selective in the political and as no evidence in the social, security/conflict, and Internet tools areas in 2009.[1] There is no individual ONI country profile for Mauritania, but it is included in the ONI regional overview for the Middle East and North Africa.[255]

There were no government restrictions on access to the Internet or reports that the government monitored email or Internet chat rooms in 2010. Individuals and groups could engage in the peaceful expression of views via the Internet, including by e-mail. There is a law prohibiting child pornography with penalties of two months to one year imprisonment and a 160,000 to 300,000 ouguiya ($550 to $1,034) fine.[256]

Between 16 March and 19 March 2009 and again on 25 June 2009 the news Web site Taqadoumy was blocked.[255][257] On 26 February 2010, Hanevy Ould Dehah, director of Taqadoumy, received a presidential pardon after being detained since December 2009 despite having served his sentence for crimes against Islam and paying all imposed fines and legal fees. Dehah, who was originally arrested in June 2009 on charges of defamation of presidential candidate Ibrahima Sarr for publishing an article stating that Sarr bought a house with campaign money from General Aziz. Dehah, was sentenced in August 2009 to six months in prison and fined 30,000 ouguiya ($111) for committing acts contrary to Islam and decency. The sentencing judge accused Dehah of creating a space allowing individuals to express anti-Islamic and indecent views, based on a female reader's comments made on the Taqadoumy site calling for increased sexual freedom.[256]

Malaysia

Malaysia

- Rated "partly free" by Freedom House in Freedom on the Net in 2009 (score 41), 2011 (score 41), 2012 (score 43), 2013 (score 44), 2014 (score 42), and 2015 (score 43).[258][259][260][261][262][263]

- Listed as no evidence in the political, social, conflict/security, and Internet tools areas by ONI in May 2007.[11]

- Listed as under surveillance by RWB in 2008, 2009, and from 2011 to the present.[3]

There have been mixed messages and confusion regarding Internet censorship in Malaysia. Internet content is officially uncensored, and civil liberties assured, though on numerous occasions the government has been accused of filtering politically sensitive sites. Any act that curbs internet freedom is theoretically contrary to the Multimedia Act signed by the government of Malaysia in the 1990s. However, pervasive state controls on traditional media spill over to the Internet at times, leading to self-censorship and reports that the state investigates and harasses bloggers and cyber-dissidents.[264]

In April 2011, prime minister Najib Razak repeated promises that Malaysia will never censor the Internet.[265]

On June 11, however, the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC) ordered ISPs to block 10 websites for violating the Copyright Act.[266] This led to the creation of a new Facebook page, "1M Malaysians Don't Want SKMM Block File Sharing Website".[267]

In May 2013, leading up to the 13th Malaysian General Election, there were reports of access to YouTube videos critical of the Barisan National Government and to pages of Pakatan Rakyat political leaders in Facebook being blocked. Analysis of the network traffic showed that ISPs were scanning the headers and actively blocking requests for the videos and Facebook pages.[268] [269]

Moldova

Moldova

- Listed as selective in the political area and as no evidence in social, conflict/security, and Internet tools by ONI in December 2010.[11]

While State authorities have interfered with mobile and Internet connections in an attempt to silence protestors and influence the results of elections, Internet users in Moldova enjoy largely unfettered access despite the government’s restrictive and increasingly authoritarian tendencies. Evidence of second- and third-generation controls is mounting. Although filtering does not occur at the backbone level, the majority of filtering and surveillance takes place at the sites where most Moldovans access the Internet: Internet cafés and workplaces. Moldovan security forces have developed the capacity to monitor the Internet, and national legislation concerning ‘‘illegal activities’’ is strict.[270]

Morocco

Morocco

- Rated "partly free" by Freedom House in Freedom on the Net in 2013 (score 42), 2014 (score 44), and 2015 (score 43).[271][272][273]

- Listed as selective in the social, conflict/security, and Internet tools areas and as no evidence in political by ONI in August 2009.[11]

Internet access in Morocco is, for the most part, open and unrestricted. Morocco’s Internet filtration regime is relatively light and focuses on a few blog sites, a few highly visible anonymizers, and for a brief period in May 2007, the video sharing Web site YouTube.[274] ONI testing revealed that Morocco no longer filters a majority of sites in favor of independence of the Western Sahara, which were previously blocked. The filtration regime is not comprehensive, that is to say, similar content can be found on other Web sites that are not blocked. On the other hand, Morocco has started to prosecute Internet users and bloggers for their online activities and writings.[275]

Northern Cyprus

Northern Cyprus

Rwanda

Rwanda

- Rated "partly free" by Freedom House in Freedom on the Net in 2011 (score 50), 2012 (score 51), 2013 (score 48), 2014 (score 50), and 2015 (score 50).[276][277][278][279][280]

- Not individually classified by ONI.

- Identified in Freedom on the Net 2012 as one of seven countries that were at particular risk of suffering setbacks related to Internet freedom in late 2012 and in 2013. The Internet in these countries was described at the time as being a relatively open and unconstrained space for free expression, but the countries also typically featured a repressive environment for traditional media and had recently considered or introduced legislation that would negatively affect Internet freedom.[7]

The law does not provide for government restrictions on access to the Internet, but there are reports that the government blocks access to Web sites within the country that are critical of the government. In 2012 and 2013, some independent online news outlets and opposition blogs were intermittently inaccessible. Some opposition sites continue to be blocked on some ISPs in early 2013, including Umusingi and Inyenyeri News, which were first blocked in 2011.[281]

The constitution provides for freedom of speech and press "in conditions prescribed by the law." The government at times restricts these rights. Laws prohibit promoting divisionism, genocide ideology, and genocide denial, "spreading rumors aimed at inciting the population to rise against the regime", expressing contempt for the Head of State, other high-level public officials, administrative authorities or other public servants, and slander of foreign and international officials and dignitaries. These acts or expression of these viewpoints sometimes results in arrest, harassment, or intimidation. Numerous journalists practice self-censorship.[281]

The constitution and law prohibit arbitrary interference with privacy, family, home, or correspondence; however, there are numerous reports the government monitors homes, telephone calls, e-mail, Internet chat rooms, other private communications, movements, and personal and institutional data. In some cases monitoring has led to detention and interrogation by State security forces (SSF).[281]

Singapore

Singapore

- Rated "partly free" by Freedom House in Freedom on the Net in 2014 (score 40) and 2015 (score 41).[282][283]

- Listed as selective in the social area and as no evidence in political, conflict/security, and Internet tools by ONI in May 2007.[11]

The Republic of Singapore engages in the Internet filtering, blocking only the original set of 100 mass-impactable websites. However, the state employs a combination of licensing controls and legal pressures to regulate Internet access and to limit the presence of objectionable content and conduct online.[284]

In 2005 and 2006 three people were arrested and charged with sedition for posting racist comments on the Internet, of which two have been sentenced to imprisonment.[285]

The Media Development Authority maintains a confidential list of blocked websites that are inaccessible within the country.[286] The Media Development Authority exerts control over all the ISPs to ensure it is not accessible unless there is an extension called "Go Away MDA".[287]

On 8 October 2012, the NTUC executive director, Amy Cheong was fired after posting racist comments on the Internet.[288]

In July 2014, the government made plans to block The Pirate Bay and 45 file sharing websites, after the Copyright Act 2014 was amended.[289]

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka

- Rated "partly free" by Freedom House in Freedom on the Net in 2012 (score 55), 2013 (score 58), 2014 (score 58), and 2015 (score 47).[290][291][292][293]

- Classified by ONI as no evidence of filtering in 2009.[1] There is no individual ONI country profile for Sri Lanka, but it is included in the regional overview for Asia.[294]

- Listed as Under Surveillance by RWB in 2008, 2009, and from 2011 to the present.[3]

Several political and news websites, including tamilnet.com and lankanewsweb.com have been blocked within the country.[295] The Sri Lanka courts have ordered hundreds of adult sites blocked to "protect women and children".[296][297]

In October and November 2011 the Sri Lankan Telecommunication Regulatory Commission blocked the five websites, www.lankaenews.com, srilankamirror.com, srilankaguardian.com, paparacigossip9.com, and www.lankawaynews.com, for what the government alleges as publishing reports that amount to "character assassination and violating individual privacy" and damaging the character of President Mahinda Rajapaksa, ministers and senior government officials. The five sites have published material critical of the government and alleged corruption and malfeasance by politicians.[298]

Tajikistan

Tajikistan

- Listed as selective in the political area and as no evidence as in social, conflict/security, and Internet tools by ONI in December 2010.[11]

Internet penetration remains low in Tajikistan because of widespread poverty and the relatively high cost of Internet access. Internet access remains largely unrestricted, but emerging second-generation controls have threatened to erode these freedoms just as Internet penetration is starting to affect political life in the country. In the run-up to the 2006 presidential elections, ISPs were asked to voluntarily censor access to an opposition Web site, and other second-generation controls have begun to emerge.[299]

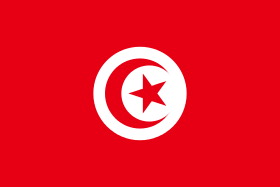

Tunisia

Tunisia

- Rated "not free" by Freedom House in Freedom on the Net in 2009 (score 76) and 2011 (score 81) and as "partly free" in 2012 (score 46), 2013 (score 41), 2014 (score 39), and 2015 (score 38).[300][301][302][303][304][305]

- Listed as no evidence in the political, social, conflict/security, and Internet tools areas by ONI in 2012.[1]

- Listed as Under Surveillance by RWB from 2011 to the present.[3]

Internet censorship in Tunisia significantly decreased in January 2011, following the ouster of President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, as the new acting government:[306][307]

- proclaimed complete freedom of information and expression as a fundamental principle,

- abolished the information ministry, and

- removed filters on social networking sites such as Facebook and YouTube.

Some Internet censorship reemerged when in May 2011:

- the Permanent Military Tribunal of Tunis ordered four Facebook pages blocked for attempting "to damage the reputation of the military institution and, its leaders, by the publishing of video clips and, the circulation of comments and, articles that aim to destabilize the trust of citizens in the national army, and spread disorder and chaos in the country",[308][309] and

- a court ordered the Tunisian Internet Agency (ATI) to block porn sites on the grounds that they posed a threat to minors and Muslim values.[310]

Prior to January 2011 the Ben Ali regime had blocked thousands of websites (such as pornography, mail, search engine cached pages, online documents conversion and translation services) and peer-to-peer and FTP transfer using a transparent proxy and port blocking. Cyber dissidents including pro-democracy lawyer Mohammed Abbou were jailed by the Tunisian government for their online activities.[311]

Turkey

Turkey

- Rated "partly free" in Freedom on the Net by Freedom House in 2009 and 2011-2015 (scores 42, 45, 46, 49, 55, and 58).[312][313][314][315][316][317]

- Listed as selective in the political, social, and Internet tools areas and as no evidence of filtering in the conflict/security area by ONI in December 2010.[11]

- Listed as under surveillance by RWB since 2010.[3]