Intercultural communication

Intercultural communication is a form of communication that aims to share information across different cultures and social groups. It is used to describe the wide range of communication processes and problems that naturally appear within an organization or social context made up of individuals from different religious, social, ethnic, and educational backgrounds. Intercultural communication is sometimes used synonymously with cross-cultural communication. In this sense it seeks to understand how people from different countries and cultures act, communicate and perceive the world around them. Many people in intercultural business communication argue that culture determines how individuals encode messages, what medium they choose for transmitting them, and the way messages are interpreted.[1]

With regard to intercultural communication proper, it studies situations where people from different cultural backgrounds interact. Aside from language, intercultural communication focuses on social attributes, thought patterns, and the cultures of different groups of people. It also involves understanding the different cultures, languages and customs of people from other countries. Intercultural communication plays a role in social sciences such as anthropology, cultural studies, linguistics, psychology and communication studies. Intercultural communication is also referred to as the base for international businesses. There are several cross-cultural service providers around who can assist with the development of intercultural communication skills. Research is a major part of the development of intercultural communication skills.[2][3]

Cross-cultural business communication

Cross-cultural business communication is very helpful in building cultural intelligence through coaching and training in cross-cultural communication, cross-cultural negotiation, multicultural conflict resolution, customer service, business and organizational communication. Cross-cultural understanding is not just for incoming expats. Cross-cultural understanding begins with those responsible for the project and reaches those delivering the service or content. The ability to communicate, negotiate and effectively work with people from other cultures is vital to international business.

Problems

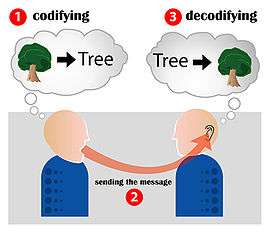

The problems in intercultural communication usually come from problems in message transmission. In communication between people of the same culture, the person who receives the message interprets it based on values, beliefs, and expectations for behavior similar to those of the person who sent the message. When this happens, the way the message is interpreted by the receiver is likely to be fairly similar to what the speaker intended. However, when the receiver of the message is a person from a different culture, the receiver uses information from his or her culture to interpret the message. The message that the receiver interprets may be very different from what the speaker intended.

Attribution is the process in which people look for an explanation of another person's behavior. When someone does not understand another, he/she usually blames the confusion on the other's "stupidity, deceit, or craziness".

Effective communication depends on the informal understandings among the parties involved that are based on the trust developed between them. When trust exists, there is implicit understanding within communication, cultural differences may be overlooked, and problems can be dealt with more easily. The meaning of trust and how it is developed and communicated vary across societies. Similarly, some cultures have a greater propensity to be trusting than others.

Nonverbal communication is behavior that communicates without words—though it often may be accompanied by words. Minor variations in body language, speech rhythms, and punctuality often cause mistrust and misperception of the situation among cross-cultural parties.

Kinesic behavior is communication through body movement—e.g., posture, gestures, facial expressions and eye contact. The meaning of such behavior varies across countries.

Occulesics are a form of kinesics that includes eye contact and the use of the eyes to convey messages.

Proxemics concern the influence of proximity and space on communication (e.g., in terms of personal space and in terms of office layout). For example, space communicates power in the US and Germany.

Paralanguage refers to how something is said, rather than the content of what is said—e.g., rate of speech, tone and inflection of voice, other noises, laughing, yawning, and silence.

Object language or material culture refers to how we communicate through material artifacts—e.g., architecture, office design and furniture, clothing, cars, cosmetics, and time. In monochronic cultures, time is experienced linearly and as something to be spent, saved, made up, or wasted. Time orders life, and people tend to concentrate on one thing at a time. In polychronic cultures, people tolerate many things happening simultaneously and emphasize involvement with people. In these cultures, people may be highly distractible, focus on several things at once, and change plans often.

Management

Important points to consider:

- Develop cultural sensitivity

- Anticipate the meaning the receiver will get.

- Careful encoding

- Use words, pictures, and gestures.

- Avoid slang, idioms, regional sayings.

- Selective transmission

- Build relationships, face-to-face if possible.

- Careful decoding of feedback

- Get feedback from multiple parties.

- Improve listening and observation skills.

- Follow-up actions

Facilitation

There is a connection between a person's personality traits and the ability to adapt to the host-country's environment—including the ability to communicate within that environment.

Two key personality traits are openness and resilience. Openness includes traits such as tolerance for ambiguity, extrovertedness, and open-mindedness. Resilience includes having an internal locus of control, persistence, tolerance for ambiguity, and resourcefulness.

These factors, combined with the person's cultural and racial identity and level of preparedness for change, comprise that person's potential for adaptation.

Theories

The following types of theories can be distinguished in different strands: focus on effective outcomes, on accommodation or adaption, on identity negotiation and management, on communication networks, on acculturation and adjustment.[4]

Social engineering effective outcomes

- Cultural convergence

- In a relatively closed social system in which communication among members is unrestricted, the system as a whole will tend to converge over time toward a state of greater cultural uniformity. The system will tend to diverge toward diversity when communication is restricted.[5]

- Communication accommodation theory

- This theory focuses on linguistic strategies to decrease or increase communicative distances.

- Intercultural adaption

- This theory is designed to explain how communicators adapt to each other in "purpose-related encounters", at which cultural factors need to be incorporated.[6] According to intercultural adaptation theory communicative competence is a measure of adaptation which is equated with assimilation. As Gudykunst and Kim (2003) put it, "cross-cultural adaptation process involves a continuous interplay of decultruation and acculturation that brings about change in strangers [immigrant] in the direction of assimilation, the highest degree of adaptation theoretically conceivable" (p. 360). This approach was first theorized at the height of colonialism in Victorian England by Herbert Spencer who applied a notion of adaptation he borrowed from Francis Galton to social adjustment and efficient outcomes in wealth production. Communicative competence is defined as thinking, feeling, and pragmatically behaving in ways defined as appropriate by the dominant mainstream culture. Communication competence is an outcomes based measure conceptualized as functional/operational conformity to environmental criteria such as working conditions. Beyond this, adaptation means "the need to conform" (p. 373) to mainstream "objective reality" and "accepted modes of experience" (Gudykunst and Kim, 2003, p. 378).[7] Adaptation theory advocates that immigrants and migrants "deculturize" and "unlearn" themselves and assimilate mainstream host cultural values, beliefs, goals, and modes of behavior so that they may become "fit to live with" (Gudykunst and Kim, 2003, p. 358). Adaptation is thus postulated as a zero-sum process where the minority person is conceptualized as something like a full finite container so that as some new goal or belief is added or learned something old must be "unlearned". Prominent current promoters of assimilation repeat Spencer's arguments stating that for the sake of the success of the mainstream culture ("effective progress") adaptation/assimilation must be in the direction of the dominant mainstream culture. While Spencer postulated mainstream culture as the dominant ways of thinking, feeling, and behaving, Gudykunst and Kim (2003) define the dominant group as a simple numerical majority ("differential size of the population" Gudykunst and Kim, 2003, p. 360).[7] Any tendency by the newcomer to retain their original identity (language, religious faiths, ethnic associations including attention to "ethnic media", beliefs, ways of thinking, et cetera) is defined by Gudykunst and Kim (2003) as operational/functional unfitness (p. 376), mental illness (pp. 372–373, 376), and communication incompetence, dispositions linked by Spencer and Galton and later Gudykunst and Kim (2003), to inherent personality predispositions and traits such as being close-minded (p. 369), emotionally immature (p. 381), ethnocentric (p. 376), and lacking cognitive complexity (pp. 382, 383). Conformity pressure has been defined since W. E B. Dubois in 1902 as symbolic violence especially when a minority cannot conform even if they wish to due to inherent properties such as disabilities, race, gender, ethnicity, and so forth. Forced compliance/assimilation based on majority group coercion constitutes what Pierre Bourdieu writing in the 1960s and dealing with issues of intercultural communication and conflict called symbolic violence (in English, Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge Univ Press). As Bourdieu (1977) maintains, the effect of symbolic violence such as host cultural coercion, the catalyst for "positive" cross-cultural adaptation according to Gudykunst and Kim (2003), results in the personal disintegration of the minority person's psyche. If the coercive power is great enough and the self-efficacy and self-esteem of the minority immigrant is destroyed, the effect leads to a mis-recognition of power relations situated in the social matrix of a given field. For example, in the process of reciprocal gift exchange in the Kabyle society of Algeria, where there is asymmetry in wealth between the two parties the better endowed giver "can impose a strict relation of hierarchy and debt upon the receiver."[8]

- Co-cultural theory

- In its most general form, co-cultural communication refers to interactions among underrepresented and dominant group members.[9] Co-cultures include but are not limited to people of color, women, people with disabilities, gay men and lesbians, and those in the lower social classes. Co-cultural theory, as developed by Mark P. Orbe, looks at the strategic ways in which co-cultural group members communicate with others. In addition, a co-cultural framework provides an explanation for how different persons communicate based on six factors.

The Four Distances Model (4DM)

The theory, rooted in semiotics, studies how relational distance can have an impact on intercultural communication: incommunicability and misunderstandings are strictly dependent from the feeling of "closeness" or "distance" that emerges in the interaction patterns between intercultural communicators. The 4 Distances Model defines the four main variables that can determine relational distance. Each variable has a subset of more specific hard-type (more tangible) and soft-type (mainly intangible) sub-variables:[10]

- D1 – Distance of the Self. D1A: biological differences, chronemics-timing differences between communicators emissions/decodings/feedbacks; D1B: Intangible Distances, identity/role/archetype/personality differences;

- D2 – Communication Codes Distances (Semiolinguistic Distance). Defined by D2A: communication content; – D2B: codes, subcodes, signs, symbols, different languages, different communication styles;

- D3 – Ideological and value distance: differences in D3A: core values, core beliefs, ideologies, world-views; D3B: differences in peripheral attitudes and beliefs;

- D4 – Referential distance (personal history); D4A: different experiences with external world objects, physical experiences; D4B: internal sensations world, differences in emotional past and present.

The model enables the research and monitoring on how intercultural interactions shift in time from "distance" to "closeness", or vice versa, from empathy to conflict, and from entropy to clarity, on which specific variables, and with which effects, in order to prepare specific interventions that reduce unwanted distances, conflict and miscommunications. Identifying hidden perceptions, roles, codes and values is substantial to determine the effectiveness of intercultural negotiations,[11] and the outcome of intercultural key-leader engagement as in peacekeeping operations.[12] The model has been used to analyze critical incidents in communication in intercultural crews in the International Space Station,[13] and in the analysis of communication misunderstandings that generated deadly accidents, in the case of miscommunications in intercultural crews and communication deceptions of the Costa Concordia disaster.[14][15]

Identity negotiation or management

- Identity management theory

- Identity negotiation

- Cultural identity theory

- Double-swing model

Communication networks

- Networks and outgroup communication competence

- Intracultural versus intercultural networks

- Networks and acculturation

Acculturation and adjustment

- Communication acculturation

- This theory attempts to portray "cross-cultural adaptation as a collaborative effort in which a stranger and the receiving environment are engaged in a joint effort."[16]

- Anxiety/Uncertainty management

- When strangers communicate with hosts, they experience uncertainty and anxiety. Strangers need to manage their uncertainty as well as their anxiety in order to be able to communicate effectively with hosts and then to try to develop accurate predictions and explanations for hosts' behaviors.

- Assimilation, deviance, and alienation states

- Assimilation and adaption are not permanent outcomes of the adaption process; rather, they are temporary outcomes of the communication process between hosts and immigrants. "Alienation or assimilation, therefore, of a group or an individual, is an outcome of the relationship between deviant behavior and neglectful communication."[17]

Other theories

- Meaning of meanings theory – "A misunderstanding takes place when people assume a word has a direct connection with its referent. A common past reduces misunderstanding. Definition, metaphor, feedforward, and Basic English are partial linguistic remedies for a lack of shared experience."[18]

- Face negotiation theory – "Members of collectivistic, high-context cultures have concerns for mutual face and inclusion that lead them to manage conflict with another person by avoiding, obliging, or compromising. Because of concerns for self-face and autonomy, people from individualistic, low-context cultures manage conflict by dominating or through problem solving"[19]

- Standpoint theory – An individual's experiences, knowledge, and communication behaviors are shaped in large part by the social groups to which they belong. Individuals sometimes view things similarly, but other times have very different views in which they see the world. The ways in which they view the world are shaped by the experiences they have and through the social group they identify themselves to be a part of.[20][21] "Feminist standpoint theory claims that the social groups to which we belong shape what we know and how we communicate.[22] The theory is derived from the Marxist position that economically oppressed classes can access knowledge unavailable to the socially privileged and can generate distinctive accounts, particularly knowledge about social relations."[23]

- Stranger theory – At least one of the persons in an intercultural encounter is a stranger. Strangers are a 'hyperaware' of cultural differences and tend to overestimate the effect of cultural identity on the behavior of people in an alien society, while blurring individual distinctions.

- Feminist genre theory – Evaluates communication by identifying feminist speakers and reframing their speaking qualities as models for women's liberation.

- Genderlect theory – "Male-female conversation is cross-cultural communication. Masculine and feminine styles of discourse are best viewed as two distinct cultural dialects rather than as inferior or superior ways of speaking. Men's report talk focuses on status and independence. Women's support talk seeks human connection."[24]

- Cultural critical studies theory – The theory states that the mass media impose the dominant ideology on the rest of society, and the connotations of words and images are fragments of ideology that perform an unwitting service for the ruling elite.

- Marxism – aims to explain class struggle and the basis of social relations through economics.

Intercultural competence

Intercultural communication is competent when it accomplishes the objectives in a manner that is appropriate to the context and relationship. Intercultural communication thus needs to bridge the dichotomy between appropriateness and effectiveness:[25] Proper means of intercultural communication leads to a 15% decrease in miscommunication.[26]

- Appropriateness. Valued rules, norms, and expectations of the relationship are not violated significantly.

- Effectiveness. Valued goals or rewards (relative to costs and alternatives) are accomplished.

Competent communication is an interaction that is seen as effective in achieving certain rewarding objectives in a way that is also related to the context in which the situation occurs. In other words, it is a conversation with an achievable goal that is used at an appropriate time/location.[25]

Components

Intercultural communication can be linked with identity, which means the competent communicator is the person who can affirm others' avowed identities. As well as goal attainment is also a focus within intercultural competence and it involves the communicator to convey a sense of communication appropriateness and effectiveness in diverse cultural contexts.[25]

Ethnocentrism plays a role in intercultural communication. The capacity to avoid ethnocentrism is the foundation of intercultural communication competence. Ethnocentrism is the inclination to view one's own group as natural and correct, and all others as aberrant.

People must be aware that to engage and fix intercultural communication there is no easy solution and there is not only one way to do so. Listed below are some of the components of intercultural competence.[25]

- Context: A judgement that a person is competent is made in both a relational and situational context.This means that competence is not defined as a single attribute, meaning someone could be very strong in one section and only moderately good in another. Situationally speaking competence can be defined differently for different cultures. For example, eye contact shows competence in western cultures whereas, Asian cultures find too much eye contact disrespectful.

- Appropriateness: This means that your behaviours are acceptable and proper for the expectations of any given culture.

- Effectiveness: The behaviours that lead to the desired outcome being achieved.

- Knowledge: This has to do with the vast information you have to have on the person's culture that you are interacting with. This is important so you can interpret meanings and understand culture-general and culture-specific knowledge.

- Motivations:This has to do with emotional associations as they communicate interculturally. Feelings which are your reactions to thoughts and experiences have to do with motivation. Intentions are thoughts that guide your choices, it is a goal or plan that directs your behaviour. These two things play a part in motivation.[25]

Basic tools for improvement

The following are ways to improve communication competence:

- Display of interest: showing respect and positive regard for the other person.

- Orientation to knowledge: Terms people use to explain themselves and their perception of the world.

- Empathy: Behaving in ways that shows you understand the world as others do.

- interaction management: A skill in which you regulate conversations.

- Task role behaviour: initiate ideas that encourage problem solving activities.

- Relational role behaviour: interpersonal harmony and mediation.

- Tolerance for ambiguity: The ability to react to new situations with little discomfort.

- Interaction posture: Responding to others in descriptive, non-judgemental ways.[25]

Important factors

- Proficiency in the host culture language: understanding the grammar and vocabulary.

- Understanding language pragmatics: how to use politeness strategies in making requests and how to avoid giving out too much information.

- Being sensitive and aware to nonverbal communication patterns in other cultures.

- Being aware of gestures that may be offensive or mean something different in a host culture rather than your own home culture.

- Understanding a culture's proximity in physical space and paralinguistic sounds to convey their intended meaning.[27]

Traits

- Flexibility.

- Tolerating high levels of uncertainty.

- Reflectiveness.

- Open-mindedness.

- Sensitivity.

- Adaptability.

- Engaging in divergent and systems-level thinking.[27]

Verbal communication

Verbal communication consist of messages being sent and received continuously with the speaker and the listener, it is focused on the way messages are portrayed. Verbal communication is based on language and use of expression, the tone in which the sender of the message relays the communication can determine how the message is received and in what context.

Factors that affect verbal communication:

- Tone of voice

- Use of descriptive words

- Emphasis on certain phrases

- Volume of voice

The way a message is received is dependent on these factors as they give a greater interpretation for the receiver as to what is meant by the message. By emphasizing a certain phrase with the tone of voice, this indicates that it is important and should be focused more on.

Along with these attributes, verbal communication is also accompanied with non-verbal cues. These cues make the message clearer and give the listener an indication of what way the information should be received.[28]

Example of non-verbal cues

- Facial expressions

- Hand gestures

- Use of objects

- Body movement

In terms of intercultural communication there are language barriers which are effected by verbal forms of communication. In this instance there is opportunity for miscommunication between two or more parties.[29] Other barriers that contribute to miscommunication would be the type of words chosen in conversation. do to different cultures there are different meaning in vocabulary chosen, this allows for a message between the sender and receiver to be misconstrued.[30]

Nonverbal communication

Nonverbal communication is behaviour that communicates without words—though it may often be accompanied by words. Nonverbal behaviour can include things such as

- Facial expressions and gestures

- Clothing

- Movement

- Posture

- Eye contact[31]

When these actions are paired with verbal communication, a message is created and sent out. A form of nonverbal communication is kinesic behaviour. Kinesic behaviour is communication through body movement—e.g., posture, gestures, facial expressions and eye contact. The meaning of such behaviour varies across countries and affects intercultural communication. A form of kinesic nonverbal communication is eye contact and the use of the eyes to convey messages. Overall, nonverbal communication gives clues to what is being said verbally by physical portrayals.

Nonverbal communication and kinesic is not the only way to communicate without words. Proxemics, a form of nonverbal communication, deals with the influence of proximity and space on communication. Another form of nonverbal behaviour and communication dealing with intercultural communication is paralanguage. Paralanguage refers to how something is said, rather than the content of what is said—e.g., rate of speech, tone and inflection of voice, other noises, laughing, yawning, and silence. Paralanguage will be later touched on in the verbal section of intercultural communication.

Nonverbal communication has been shown to account for between 65% and 93% of interpreted communication.[32] Minor variations in body language, speech rhythms, and punctuality often cause mistrust and misperception of the situation among cross-cultural parties. This is where nonverbal communication can cause problems with intercultural communication. Misunderstandings with nonverbal communication can lead to miscommunication and insults with cultural differences. For example, a handshake in one culture may be recognized as appropriate, whereas another culture may recognize it as rude or inappropriate.[32]

Nonverbal communication can be used without the use of verbal communication. This can be used as a coding system for people who do not use verbal behaviour to communicate in different cultures, where speaking is not allowed.[33] An facial expression can give cues to another person and send a message, without using verbal communication.

Something that usually goes unnoticed in cultures and communication is that clothing and the way people dress is used as a form of nonverbal communication. What a person wears can tell a lot about them. For example, whether someone is poor or rich, young or old or if they have specific cultures and beliefs can all be said through clothing and style. This is a form of nonverbal communication.

Overall, nonverbal communication is a very important concept in intercultural communication.

See also

References

| Library resources about Intercultural communication |

Notes

- ↑ Lauring, Jakob (2011). "Intercultural Organizational Communication: The Social Organizing of Interaction in International Encounters". Journal of Business and Communication. 48.3: 231–55.

- ↑ http://communication-design.net/3-tips-for-effective-global-communication//

- ↑ "Intercultural Communication Law & Legal Definition". Definitions.uslegal.com. Retrieved 2016-05-19.

- ↑ Cf. Gudykunst 2003 for an overview.

- ↑ Kincaid, D. L. (1988). The convergence theory of intercultural communication. In Y. Y. Kim & W. B. Gudykunst (Eds.), Theories in intercultural communication (pp. 280–298). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. p.289

- ↑ Ellingsworth, 1983.

- 1 2 Gudykunst, W. & Kim, Y. Y. (2003). Communicating with strangers: An approach to intercultural communication, 4th ed. New York: McGraw Hill.

- ↑ Bohman, J. 1999. 'Practical Reason and Cultural Constraint' in R. Shusterman (Ed.) Bourdieu: A Critical Reader, Oxford: Blackwell.

- ↑ Orbe, 1998. p.3

- ↑ Daniele Trevisani (1992), “A Semiotic Models Approach to the Analysis of Internatio-nal/Intercultural Communication”, in Proceedings of the 9th International and Intercultural Communication Conference, University of Miami, 19–21 May

- ↑ Trevisani, Daniele (2005), "Negoziazione Interculturale: Comunicazione oltre le barriere culturali", Milano, Franco Angeli (Translated title: "Intercultural Negotiation: Communication Beyond Cultural Barriers".) ISBN 9788846466006

- ↑ Commander’s Handbook for Strategic Communication and Communication Strategy, US Joint Forces Command, 24 June 2010

- ↑ Stene, Trine Marie; Trevisani, Daniele; Danielsen, Brit-Eli (Dec 16, 2015). "Preparing for the unexpected.". European Space Agency (ESA) Moon 2020-2030 Conference Proceedings. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.4260.9529.

- ↑ "Harbour master's log reveals how tragedy unfolded". Irish Independent. 22 January 2012. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- ↑ Robert Marquand (18 January 2012). "Costa Concordia: Top 4 'deceptions' by ship's captain". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 19 January 2012.

- ↑ Kim Y.Y.(1995), p.192

- ↑ Mc Guire and McDermott, 1988, p. 103

- ↑ Griffin (2000), p. 492

- ↑ Griffin (2000), p. 496

- ↑ Social group

- ↑ Collins, P. H. (1990). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. Boston: Unwin Hyman.

- ↑ Wood, 2005

- ↑ https://read.amazon.com/?asin=B00DG8M7EU

- ↑ Griffin (2000), p. 497

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 (Lustig & Koester, 2010)

- ↑ "Facts and Figures". Cultural Candor Inc.

- 1 2 (Intercultural Communication)

- ↑ Hinde, R. A. (1972). Non-verbal communication; edited by R. A. Hinde. -. Cambridge [Eng.]: University Press, 1972.

- ↑ Esposito, A. (2007). Verbal and nonverbal communication behaviours [electronic resource] : COST Action 2102 International Workshop, Vietri sul Mare, Italy, March 29–31, 2007 : revised selected and invited papers / Anna Esposito ... [et al.] (eds.). Berlin ; New York : Springer, c2007.

- ↑ Scollon, R., & Scollon, S. K. (2001). Intercultural communication : a discourse approach / Ron Scollon and Suzanne Wong Scollon. Malden, MA : Blackwell Publishers, 2001

- ↑ Akmajian Adrian, Demers Richard, Farmer Ann, Harnish Robert. 2001. Linguistics An Introduction to Language and Communication. Communication and Cognitive Science. pp.355.

- 1 2 Samovar Larry, Porter Richard, McDaniel Edwin, Roy Carolyn. 2006. Intercultural Communication A Reader. Nonverbal Communication. pp13.

- ↑ Morgan Carol, Byram Michael. 1994. Teaching and Learning Language and Culture. Culture in Language Learning. pp.5.

Bibliography

- Bhawuk, D. P. & Brislin, R. (1992). "The Measurement of Intercultural Sensitivity Using the Concepts of Individualism and Collectivism", International Journal of Intercultural Relations(16), 413–36.

- Ellingsworth, H.W. (1983). "Adaptive intercultural communication", in: Gudykunst, William B (ed.), Intercultural communication theory, 195–204, Beverly Hills: Sage.

- Fleming, S. (2012). "Dance of Opinions: Mastering written and spoken communication for intercultural business using English as a second language" ISBN 9791091370004

- Graf, A. & Mertesacker, M. (2010). "Interkulturelle Kompetenz als globaler Erfolgsfaktor. Eine explorative und konfirmatorische Evaluation von fünf Fragebogeninstrumenten für die internationale Personalauswahl", Z Manag(5), 3–27.

- Griffin, E. (2000). A first look at communication theory (4th ed.). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill. n/a.

- Gudykunst, William B., & M.R. Hammer.(1988). "Strangers and hosts: An uncertainty reduction based theory of intercultural adaption" in: Kim, Y. & W.B. Gudykunst (eds.), Cross-cultural adaption, 106–139, Newbury Park: Sage.

- Gudykunst, William B. (2003), "Intercultural Communication Theories", in: Gudykunst, William B (ed.), Cross-Cultural and Intercultural Communication, 167–189, Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Hidasi, Judit (2005). Intercultural Communication: An outline, Sangensha, Tokyo.

- Hogan, Christine F. (2013), "Facilitating cultural transitions and change, a practical approach", Stillwater, USA: 4 Square Books. (Available from Amazon), ISBN 978-1-61766-235-5

- Hogan, Christine F. (2007), "Facilitating Multicultural Groups: A Practical Guide", London: Kogan Page, ISBN 0749444924

- Kelly, Michael., Elliott, Imelda & Fant, Lars. (eds.) (2001). Third Level Third Space – Intercultural Communication and Language in European Higher Education. Bern: Peter Lang.

- Kim Y.Y.(1995), "Cross-Cultural adaption: An integrative theory.", in: R.L. Wiseman (Ed.)Intercultural Communication Theory, 170 – 194, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Messner, W. & Schäfer, N. (2012), "The ICCA™ Facilitator's Manual. Intercultural Communication and Collaboration Appraisal", London: Createspace.

- Messner, W. & Schäfer, N. (2012), "Advancing Competencies for Intercultural Collaboration", in: U. Bäumer, P. Kreutter, W. Messner (Eds.) "Globalization of Professional Services", Heidelberg: Springer.

- McGuire, M. & McDermott, S. (1988), "Communication in assimilation, deviance, and alienation states", in: Y.Y. Kim & W.B. Gudykunst (Eds.), Cross-Cultural Adaption, 90 – 105, Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Oetzel, John G. (1995), "Intercultural small groups: An effective decision-making theory", in Wiseman, Richard L (ed.), Intercultural communication theory, 247–270, Thousands Oaks: Sage.

- Spitzberg, B. H. (2000). "A Model of Intercultural Communication Competence", in: L. A. Samovar & R. E. Porter (Ed.) "Intercultural Communication – A Reader", 375–387, Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing.

- Trevisani, Daniele (2005), "Negoziazione Interculturale: Comunicazione oltre le barriere culturali", Milano, Franco Angeli (Translated title: "Intercultural Negotiation: Communication Beyond Cultural Barriers".) ISBN 9788846466006

- Wiseman, Richard L. (2003), "Intercultural Communication Competence", in: Gudykunst, William B (ed.), Cross-Cultural and Intercultural Communication, 191–208, Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Lustig, M. W., & Koester, J. (2010). Intercultural competence : interpersonal communication across cultures / Myron W. Lustig, Jolene Koester. Boston : Pearson/Allyn & Bacon, c2010