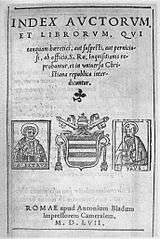

Index Librorum Prohibitorum

The Index Librorum Prohibitorum (English: List of Prohibited Books) was a list of publications deemed heretical, anti-clerical or lascivious, and therefore banned by the Catholic Church.[1]

The 9th century witnessed the creation of what is considered to be the first index, called the Decretem Glasianum, but it was never officially authorized.[2] Much later, a first version (the Pauline Index) was promulgated by Pope Paul IV in 1559, which Paul F. Grendler believed marked "the turning-point for the freedom of enquiry in the Catholic world", and which lasted less than a year, being then replaced by what was called the Tridentine Index (because it was authorized at the Council of Trent), which relaxed aspects of the Pauline Index that had been criticized and had prevented its acceptance.[1]

The 20th and final edition appeared in 1948, and the Index was formally abolished on 14 June 1966 by Pope Paul VI.[3][4][5]

The aim of the list was to protect the faith and morals of the faithful by preventing the reading of heretical and immoral books. Books thought to contain such errors included works by astronomers such as Johannes Kepler's Epitome astronomiae Copernicanae, which was on the Index from 1621 to 1835, and by philosophers, like Immanuel Kant's Critique of Pure Reason. The various editions of the Index also contained the rules of the Church relating to the reading, selling and pre-emptive censorship of books—editions and translations of the Bible that had not been approved by the Church could be banned.[6]

Catholic canon law still recommends that works concerning sacred Scripture, theology, canon law, church history, and any writings which specially concern religion or morals, be submitted to the judgment of the local ordinary.[7] The local ordinary consults someone whom he considers competent to give a judgment and, if that person gives the nihil obstat ("nothing forbids") the local ordinary grants the imprimatur ("let it be printed").[8] Members of religious institutes require the imprimi potest (it can be printed) of their major superior to publish books on matters of religion or morals.[9]

Some of the scientific theories in works that were on early editions of the Index have long been routinely taught at Catholic universities worldwide; for example the general prohibition of books advocating heliocentrism was only removed from the Index in 1758, but already in 1742 two Minims mathematicians had published an edition of Isaac Newton's Principia Mathematica (1687) with commentaries and a preface stating that the work assumed heliocentrism and could not be explained without it.[10] The burning at the stake of Giordano Bruno,[11] whose entire works were placed on the Index in 1603,[12] was because of teaching the heresy of pantheism, not for heliocentrism or other scientific views.[13][14][15] Antonio Rosmini-Serbati, one of whose works was on the Index, was beatified in 2007.[16] The developments since the abolition of the Index signify "the loss of relevance of the Index in the 21st century."[17]

A complete list of the authors and writings present in the successive editions of the Index is given in J. Martínez de Bujanda, Index Librorum Prohibitorum, 1600–1966.[18] A list of the books that were on the Index can be found on the World Wide Web.[19]

Background and history

European restrictions on the right to print

The historical context in which the Index appeared involved the early restrictions on printing in Europe. The refinement of moveable type and the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg around 1440 changed the nature of book publishing, and the mechanism by which information could be disseminated to the public.[20] Books, once rare and kept carefully in a small number of libraries, could be mass-produced and widely disseminated.

In the 16th century, both the churches and governments in most European countries attempted to regulate and control printing because it allowed for rapid and widespread circulation of ideas and information. The Protestant Reformation generated large quantities of polemical new writing by and within both the Catholic and Protestant camps, and religious subject-matter was typically the area most subject to control. While governments and church encouraged printing in many ways, which allowed the dissemination of Bibles and government information, works of dissent and criticism could also circulate rapidly. As a consequence, governments established controls over printers across Europe, requiring them to have official licenses to trade and produce books.[21][22]

The early versions of the Index began to appear from 1529 to 1571. In the same time frame, in 1557 the English Crown aimed to stem the flow of dissent by chartering the Stationers' Company. The right to print was restricted to two universities and to the 21 existing printers in the city of London, which had between them 53 printing presses.

The French crown also tightly controlled printing, and the printer and writer Etienne Dolet was burned at the stake for atheism in 1546. The 1551 Edict of Châteaubriant comprehensively summarized censorship positions to date, and included provisions for unpacking and inspecting all books brought into France.[23][24] The 1557 Edict of Compiègne applied the death penalty to heretics and resulted in the burning of a noblewoman at the stake.[25] Printers were viewed as radical and rebellious, with 800 authors, printers and book dealers being incarcerated in the Bastille before it was stormed in 1789.[26] At times, the prohibitions of church and state followed each other, e.g. René Descartes was placed on the Index in the 1660s and the French government prohibited the teaching of Cartesianism in schools in the 1670s.[27]

The 1710 introduction of Statute of Anne in England (and later copyright laws in France) eased this situation. However, historian Eckhard Höffner claims that copyright laws and their restrictions acted as a barrier to progress in those countries for over a century, since British publishers could print valuable knowledge in limited quantities for the sake of profit; while the German economy prospered in the same time frame since there were no restrictions.[28][29]

Early indices (1529–1571)

The first list of the kind was not published in Rome, but in Catholic Netherlands (1529); Venice (1543) and Paris (1551) under the terms of the Edict of Châteaubriant followed this example. By mid-century, in the tense atmosphere of wars of religion in Germany and France, both Protestant and Catholic authorities reasoned that only control of the press, including a catalog of prohibited works, coordinated by ecclesiastic and governmental authorities could prevent the spread of heresy.[30]

The first Roman Index was printed in 1557 under the direction of Pope Paul IV (1555–1559), but then withdrawn for unclear reasons.[31] In 1559, a new index was finally published, banning the entire works of some 550 authors in addition to the individual proscribed titles:[31][32] "The Pauline Index felt that the religious convictions of an author contaminated all his writing."[30] The work of the censors was considered too severe and met with much opposition even in Catholic intellectual circles; after the Council of Trent had authorised a revised list prepared under Pope Pius IV, the so-called Tridentine Index was promulgated in 1564; it remained the basis of all later lists until Pope Leo XIII, in 1897, published his Index Leonianus.

The blacklisting of some Protestant scholars even when writing on subjects a modern reader would consider outside the realm of dogma meant that, unless they obtained a dispensation, obedient Catholic thinkers were denied access to works including: botanist Conrad Gesner's Historiae animalium; the botanical works of Otto Brunfels; those of the medical scholar Janus Cornarius; to Christoph Hegendorff or Johann Oldendorp on the theory of law; Protestant geographers and cosmographers like Jacob Ziegler or Sebastian Münster; as well as anything by Protestant theologians like Martin Luther, John Calvin or Philipp Melancthon.[33] Among the inclusions was the Libri Carolini, a theological work from the 9th century court of Charlemagne, which was published in 1549 by Bishop Jean du Tillet and which had already been on two other lists of prohibited books before being inserted into the Tridentine Index.[34]

Sacred Congregation of the Index (1571–1917)

In 1571 a special congregation was created, the Sacred Congregation of the Index, which had the specific task to investigate those writings that were denounced in Rome as being not exempt of errors, to update the list of Pope Pius IV regularly and also to make lists of required corrections in case a writing was not to be condemned absolutely but only in need of correction; it was then listed with a mitigating clause (e.g., donec corrigatur (forbidden until corrected) or donec expurgetur (forbidden until purged)).

Several times a year, the congregation held meetings. During the meetings, they reviewed various works and documented those discussions. In between the meetings was when the works to be discussed were thoroughly examined, and each work was scrutinized by two people. At the meetings, they collectively decided whether or not the works should be included in the Index. Ultimately, the pope was the one who had to approve of works being added or removed from the Index. It was the documentation from the meetings of the congregation that aided the pope in making his decision.[35]

This sometimes resulted in very long lists of corrections, published in the Index Expurgatorius, which was cited by Thomas James in 1627 as "an invaluable reference work to be used by the curators of the Bodleian library when listing those works particularly worthy of collecting".[36] Prohibitions made by other congregations (mostly the Holy Office) were simply passed on to the Congregation of the Index, where the final decrees were drafted and made public, after approval of the Pope (who always had the possibility to condemn an author personally—there are only a few examples of such condemnation, including those of Lamennais and Hermes).

An update to the Index was made by Pope Leo XIII, in the 1897 apostolic constitution Officiorum ac Munerum, known as the "Index Leonianus".[37] Subsequent editions of the Index were more sophisticated; they graded authors according to their supposed degree of toxicity, and they marked specific passages for expurgation rather than condemning entire books.[38]

The Sacred Congregation of the Inquisition of the Roman Catholic Church later became the Holy Office, and since 1965 has been called the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. The Congregation of the Index was merged with the Holy Office in 1917, by the Motu Proprio "Alloquentes Proxime" of Pope Benedict XV; the rules on the reading of books were again reelaborated in the new Codex Iuris Canonici. From 1917 on, the Holy Office (again) took care of the Index.

Holy Office (1917–1966)

While individual books continued to be forbidden, the last edition of the Index to be published appeared in 1948. This 20th[5] edition contained 4,000 titles censored for various reasons: heresy, moral deficiency, sexual explicitness, and so on. That some atheists, such as Schopenhauer and Nietzsche, were not included was due to the general (Tridentine) rule that heretical works (i.e., works that contradict Catholic dogma) are ipso facto forbidden. Some important works are absent simply because nobody bothered to denounce them.[40] Many actions of the congregations were of a definite political content.[41] Among the significant listed works of the period was the Nazi philosopher Alfred Rosenberg's Myth of the Twentieth Century for scorning and rejecting "all dogmas of the Catholic Church, indeed the very fundamentals of the Christian religion".[39]

Abolition (1966)

On 7 December 1965, Pope Paul VI issued the Motu Proprio Integrae servandae that reorganized the Holy Office as the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.[42] The Index was not listed as being a part of the newly constituted congregation's competence, leading to questioning whether it still was. This question was put to Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani, pro-prefect of the congregation, who responded in the negative.[43] The Cardinal also indicated in his response that there was going to be a change in the Index soon.

A June 1966 CDF notification announced that, while the Index maintained its moral force, in that it taught Christians to beware, as required by the natural law itself, of those writings that could endanger faith and morality, it no longer had the force of ecclesiastical positive law with the associated penalties.[44]

Scope and impact

Censorship and enforcement

The Index was not simply a reactive work. Roman Catholic authors had the opportunity to defend their writings and could prepare a new edition with necessary corrections or deletions, either to avoid or to limit a ban. Pre-publication censorship was encouraged.

The Index was enforceable within the Papal States, but elsewhere only if adopted by the civil powers, as happened in several Italian states.[45] Other areas adopted their own lists of forbidden books. In the Holy Roman Empire book censorship, which preceded publication of the Index, came under control of the Jesuits at the end of the 16th century, but had little effect, since the German princes within the empire set up their own systems.[46] In France it was French officials who decided what books were banned[46] and the Church's Index was not recognized.[47] Spain had its own Index Librorum Prohibitorum, which corresponded largely to the Church's,[48] but also included a list of books that were allowed once the forbidden part (sometimes a single sentence) was removed or "expurgated".[49]

Continued moral obligation

On 14 June 1966, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith responded to inquiries it had received regarding the continued moral obligation concerning books that had been listed in the Index. The response spoke of the books as examples of books dangerous to faith and morals, all of which, not just those once included in the Index, should be avoided regardless of the absence of any written law against them. The Index, it said, retains its moral force "inasmuch as" (quatenus) it teaches the conscience of Christians to beware, as required by the natural law itself, of writings that can endanger faith and morals, but it (the Index of Forbidden Books) no longer has the force of ecclesiastical law with the associated censures.[50]

The congregation thus placed on the conscience of the individual Christian the responsibility to avoid all writings dangerous to faith and morals, while at the same time abolishing the previously existing ecclesiastical law and the relative censures,[51] without thereby declaring that the books that had once been listed in the various editions of the Index of Prohibited Books had become free of error and danger.

In a letter of 31 January 1985 to Cardinal Giuseppe Siri, regarding the book Poem of the Man God, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (then Prefect of the Congregation, who later became Pope Benedict XVI), referred to the 1966 notification of the Congregation as follows: "After the dissolution of the Index, when some people thought the printing and distribution of the work was permitted, people were reminded again in L'Osservatore Romano (15 June 1966) that, as was published in the Acta Apostolicae Sedis (1966), the Index retains its moral force despite its dissolution. A decision against distributing and recommending a work, which has not been condemned lightly, may be reversed, but only after profound changes that neutralize the harm which such a publication could bring forth among the ordinary faithful."[52]

Changing judgments

In the course of centuries, editions of the Index Librorum Prohibitorum saw deletions as well as additions of content. Thus writings by Antonio Rosmini-Serbati were placed on the Index in 1849 but were removed by 1855, and Pope John Paul II mentioned Rosmini's work as a significant example of "a process of philosophical enquiry which was enriched by engaging the data of faith".[53] The 1758 edition of the Index removed the general prohibition of works advocating heliocentrism as a fact rather than a hypothesis.[54]

Some of the ideas that were part of the charges of heresy (along with many other purely religious ones) against Giordano Bruno, who in 1600 was burned alive at the stake in Campo de' Fiori in Rome, now form some of the foundations of modern cosmology.[55]

With the changing standards by which items are judged as immoral and with books being produced in some countries at a rate of one every few minutes, the maintenance of any kind of Index would have proven almost impossible, in any case.[56][57][58]

Listed works and authors

The Index included a number of authors and intellectuals whose works are widely read today in most leading universities and are now considered as the foundations of science, e.g. Kepler's New Astronomy, his Epitome of Copernican Astronomy, and his World Harmony were quickly placed on the Index after their publication.[59] Other noteworthy intellectual figures on the Index include Jean-Paul Sartre, Montaigne, Voltaire, Denis Diderot, Victor Hugo, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, André Gide, Emanuel Swedenborg, Baruch Spinoza, Immanuel Kant, David Hume, René Descartes, Francis Bacon, Thomas Browne, John Milton, John Locke, Nicolaus Copernicus, Galileo Galilei, Blaise Pascal, and Hugo Grotius. Charles Darwin's works were never included.[60]

In many cases, an author's opera omnia (his complete works) were forbidden. Most of these were inserted in the Index at a time when the Index itself stated that the prohibition of someone's opera omnia did not cover works whose contents did not concern religion and were not forbidden by the general rules of the Index, but this explanation was omitted in the 1929 edition, an omission that was officially interpreted in 1940 as meaning that thenceforth "opera omnia" covered all the author's works without exception.[61]

Cardinal Ottaviani stated in April 1966 there was too much contemporary literature and the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith could not keep up with it.[62]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Grendler, Paul F. "Printing and censorship" in The Cambridge History of Renaissance Philosophy, Charles B. Schmitt, ed. (Cambridge University Press, 1988, ISBN 978-0-52139748-3) pp. 45–46

- ↑ Lenard, M (2007). "On the Origin, Development and Demise of the Index Librorum Prohibitorum". Journal of Access Services. 3 (4).

- ↑ The Church in the Modern Age, (Volume 10) by Hubert Jedin, John Dolan, Gabriel Adriányi 1981 ISBN 082450013X, page 168

- ↑ Cambridge University on Index.

- 1 2 Encyclopaedia Britannica: Index Librorum Prohibitorum

- ↑ Index Librorum Prohibitorum, 1559, Regula Quarta ("Rule 4")

- ↑ Code of Canon Law, canon 827 §3

- ↑ Code of Canon Law, canon 830

- ↑ Code of Canon Law, canon 832

- ↑ John L.Heilbron, Censorship of Astronomy in Italy after Galileo (in McMullin, Ernan ed., The Church and Galileo, University of Notre Dame Press, Notre Dame, 2005, p. 307, IN. ISBN 0-268-03483-4)

- ↑ Paula Findlen, "A Hungry Mind: Giordano Bruno, Philosopher and Heretic", The Nation, September 10, 2008. "Campo de' Fiori was festooned with flags bearing Masonic symbols. Fiery speeches were made by politicians, scholars and atheists about the importance of commemorating Bruno as one of the most original and oppressed freethinkers of his age." Accessed on 19 September 2008

- ↑ Index of Prohibited Books, Revised, Vatican Polyglot Press, 1930

- ↑ Paul Henry Michel. The Cosmology of Giordano Bruno. R.E.W. Maddison, translator. Cornell University Press 1962

- ↑ The [Old] Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 3.: 1908.

- ↑ Angelo, Joseph A. Life in the Universe. p. 7.

- ↑ Cardinal Saraiva calls new blessed Antonio Rosmini “giant of the culture”

- ↑ Robert Wilson, 1997 Astronomy Through the Ages ISBN 0-7484-0748-0

- ↑ Jesús Martínez de Bujanda, Index Librorum Prohibitorum, 1600–1966 (v. 11 in series Index des livres interdits) (Droz, Geneva, 2002 ISBN 978-2-60000818-1)

- ↑ Searchable database of Index Librorum Prohibitorum at Beacon for Freedom of Expression

- ↑ McLuhan, Marshall (1962), The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man (1st ed.), University of Toronto Press, ISBN 978-0-8020-6041-9 page 124

- ↑ MacQueen, Hector L.; Waelde, Charlotte; Laurie, Graeme T. (2007). Contemporary Intellectual Property: Law and Policy. Oxford University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-19-926339-4.

- ↑ de Sola Pool, Ithiel (1983). Technologies of freedom. Harvard University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-674-87233-2.

- ↑ The Rabelais encyclopedia by Elizabeth A. Chesney 2004 ISBN 0-313-31034-3 pages 31–32

- ↑ The printing press as an agent of change by Elizabeth L. Eisenstein 1980 ISBN 0-521-29955-1 page 328

- ↑ Robert Jean Knecht, The Rise and Fall of Renaissance France: 1483–1610 2001, ISBN 0-631-22729-6 page 241

- ↑ de Sola Pool, Ithiel (1983). Technologies of freedom. Harvard University Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-674-87233-2.

- ↑ A companion to Descartes by Janet Broughton, John Peter Carriero 2007 ISBN 1-4051-2154-8 page

- ↑ Der Spiegel August 18 2010 article: No Copyright Law

- ↑ Geschichte und Wesen des Urheberrechts (History and nature of copyright) by Eckhard Höffner, July 2010 (in German) ISBN 3-930893-16-9

- 1 2 Schmitt 1991:45.

- 1 2 Studies in the History of Venice by Brown Horatio Robert Forbes p.70

- ↑ They included everything by Pietro Aretino, Machiavelli, Erasmus and Rabelais (Schmitt 1991:45).

- ↑ These authors are instanced by Schmitt 1991.

- ↑ Paul Oskar Kristeller (editor), Itinerarium Italicum (Brill 1975 ISBN 978-90-0404259-9), p. 90

- ↑ Heneghan, Thomas (2005). "Secrets Behind The Forbidden Books". America. 192 (4). Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ↑ Green, Jonathan; Karolides, Nicholas J. (2005), Encyclopedia on Censorship, Facts on File, Inc, p. 257

- ↑ Catholic encyclopedia

- ↑ Lyons, Martyn. (2011). Books: A Living History. Los Angeles, CA: Getty Publications. ISBN 978-1-60606-083-4, p. 83

- 1 2 Richard Bonney; Confronting the Nazi War on Christianity: the Kulturkampf Newsletters, 1936–1939; International Academic Publishers; Bern; 2009 ISBN 978-3-03911-904-2; p. 122

- ↑ "The works appearing on the Index are only those that ecclesiastical authority was asked to act upon" (Encyclopaedia Britannica: Index Librorum Prohibitorum).

- ↑ "The entanglement of Church and state power in many cases led to overtly political titles being placed on the Index, titles which had little to do with immorality or attacks on the Catholic faith. For example, a history of Bohemia, the Rervm Bohemica Antiqvi Scriptores Aliqvot ... by Marqvardi Freheri (published in 1602), was placed on the Index not for attacking the Church, but rather because it advocated the independence of Bohemia from the (Catholic) Austro-Hungarian Empire. Likewise, The Prince by Machiavelli was placed in the Index in 1559 after it was blamed for widespread political corruption in France (Curry, 1999, p.5)" (David Dusto, Index Librorum Prohibitorum: The History, Philosophy, and Impact of the Index of Prohibited Books).

- ↑ Paul VI, Pope (1965-12-07). "Integrae servandae". vatican.va. Retrieved 2016-07-10.

- ↑ L'Osservatore della Domenica, 24 April 1966, pg. 10.

- ↑ Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (1966-06-14). "Notification regarding the abolition of the Index of books". vatican.va. Archived from the original on 2014-03-07. Retrieved 2016-07-10.

- ↑ Stephen G. Burnett, Christian Hebraism in the Reformation Era (Brill 2012 ISBN 978-9-00422248-9), p. 236

- 1 2 Lucien Febvre, Henri Jean Martin, The Coming of the Book: The Impact of Printing 1450–1800 (Verso 1976 ISBN 978-1-85984108-2), pp. 245–246

- ↑ John Michael Lewis, Galileo in France (Peter Lang 2006 ISBN 978-0-82045768-0), p. 11

- ↑ C. B. Schmitt, Quentin Skinner, Eckhard Kessler, Renaissance Philosophy (Cambridge University Press 1988 ISBN 978-0-52139748-3), p. 48

- ↑ Bernardo de Sandoval, Archbishop of Toledo Index Librorum et Expurgatorium (Louis Sanchez Typography, Madrid 1612) Regla XII

- ↑ "Haec S. Congregatio pro Doctrina Fidei, facto verbo cum Beatissimo Patre, nuntiat Indicem suum vigorem moralem servare, quatenus Christifidelium conscientiam docet, ut ab illis scriptis, ipso iure naturali exigente, caveant, quae fidem ac bonos mores in discrimen adducere possint; eundem tamen non amplius vim legis ecclesiasticae habere cum adiectis censuris" (Acta Apostolicae Sedis 58 (1966), p. 445). Cf. Italian text published, together with the Latin, on L'Osservatore Romano of 15 June 1966)

- ↑ Post litteras apostolicas

- ↑ Poem of the Man-God

- ↑ Encyclical Fides et ratio, 74

- ↑ McMullin, Ernan, ed. The Church and Galileo. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press. 2005. ISBN 0-268-03483-4. pp. 307, 347

- ↑ New Yorker Magazine, August 25, 2008: The Forbidden World

- ↑ Roger Shattuck 1997 Forbidden Knowledge: From Prometheus to Pornography ISBN 0-15-600551-4

- ↑ New York Times: How Many Books are Too Many? July 18, 2004

- ↑ Our changing morality: a symposium by Freda Kirchwey 1972 ISBN 0-405-03866-6 page 236

- ↑ Project Galileo

- ↑ Rafael Martinez, professor of the philosophy of science at the Santa Croce Pontifical University in Rome, in speech reported on Catholic Ireland net Accessed 26 May 2009

- ↑ Jesús Martínez de Bujanda, Index librorum prohibitorum: 1600–1966 (Droz 2002 ISBN 2-600-00818-7), p. 36

- ↑ L'Osservatore della Domenica, 24 April 1966, pg. 10.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Index Librorum Prohibitorum. |

"Index Librorum Prohibitorum". Encyclopædia Britannica. 14 (11th ed.). 1911.

"Index Librorum Prohibitorum". Encyclopædia Britannica. 14 (11th ed.). 1911.- Facsimile of the 1559 index

- The complete list of banned books in 1948

- List of famous authors in the index

- "Index of Prohibited Books", The Catholic Encyclopedia (Volume VII, 1910): "The first Roman Index of Prohibited Books (Index librorum prohibitorum), published in 1559 under Paul IV, was very severe, and was therefore mitigated under that pontiff by decree of the Holy Office of 14 June of the same year. It was only in 1909 that this Moderatio Indicis librorum prohibitorum (Mitigation of the Index of Prohibited Books) was rediscovered in Codex Vaticanus lat. 3958, fol. 74, and was published for the first time."

- The ten "tridentine" rules on the censorship of books (English)

- The papal constitution Sollicita ac provida regulating the work of the Congregations of the Holy Office and of the Index (Latin)

- Vatican opens up secrets of Index of Forbidden Books, Dec 22, 2005

- Secrets Behind The Forbidden Books – America, February 7, 2005

- El Index de la Iglesia – The Roman Church Index: México, 1948.

- An index of prohibited books, by command of the present pope, Gregory XVI in 1835; being the latest specimen of the literary policy of the Church of Rome, Joseph Mendham, London: Duncan and Malcolm, 1840. Also at the archive.org.