Imprimatur

An imprimatur (from Latin, "let it be printed") is, in the proper sense, a declaration authorizing publication of a book. The term is also applied loosely to any mark of approval or endorsement.

Catholic Church

In the Catholic Church an imprimatur is an official declaration by a Church authority that a book or other printed work may be published;[1][2] it is usually only applied for and granted to books on religious topics from a Catholic perspective.

The grant of imprimatur is normally preceded by a favourable declaration (known as a nihil obstat)[3] by a person who has the knowledge, orthodoxy and prudence necessary for passing a judgement about the absence from the publication of anything that would "harm correct faith or good morals"[4] In canon law such a person is known as a censor[4] or sometimes as a censor librorum (Latin for "censor of books"). In this context, the word "censor" does not have the negative sense of prohibiting, but instead refers to the person's function of evaluating—whether positively or negatively—the doctrinal content of the publication.[5] The episcopal conference may draw up a list of persons who can suitably act as censors or can set up a commission that can be consulted, but each ordinary may make his own choice of person to act as censor.[4]

An imprimatur is not an endorsement by the bishop of the contents of a book, not even of the religious opinions expressed in it, being merely a declaration about what is not in the book.[6] In the published work, the imprimatur is sometimes accompanied by a declaration of the following tenor:

The nihil obstat and imprimatur are declarations that a book or pamphlet is free of doctrinal or moral error. No implication is contained therein that those who have granted the nihil obstat or imprimatur agree with the contents, opinions or statements expressed.[7]

The person empowered to issue the imprimatur is the local ordinary of the author or of the place of publication.[8] If he refuses to grant an imprimatur for a work that has received a favourable nihil obstat from the censor, he must inform the author of his reasons for doing so.[2] This enables the author, if he wishes, to make changes so as to overcome the ordinary's difficulty in granting approval.[9]

If further examination shows that a work is not free of doctrinal or moral error, the imprimatur granted for its publication can be withdrawn. This happened three times in the 1980s, when the Holy See judged that complaints made to it about religion textbooks for schools were well founded and ordered the bishop to revoke his approval.[10]

The imprimatur granted for a publication is not valid for later editions of the same work or for translations into another language. For these, new imprimaturs are required.[8]

The permission of the local ordinary is required for the publication of prayer books,[11] catechisms and other catechetical texts,[12] and school textbooks on Scripture, theology, canon law, church history, or religious or moral subjects.[13] It is recommended, but without obligation, that books on the last-mentioned subjects not intended to be used as school textbooks and all books dealing especially with religious or moral subjects be submitted to the local ordinary for judgement.[14]

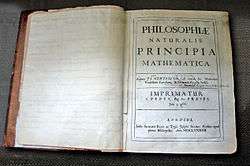

The imprimatur effectively dates from the dawn of printing, and is first seen in the printing and publishing centres of Germany and Venice;[9] many secular states or cities began to require registration or approval of published works around the same time, and in some countries such restrictions still continue, though the collapse of the Soviet bloc has reduced their number. In 2011, Bishop Kevin C. Rhoades was the first bishop to grant an imprimatur to an iPhone application.[15]

English law

English laws of 1586, 1637 and 1662 required an official licence for printing books. The 1662 act, though, required books, according to their subject, to receive the authorization, known as the imprimatur, of the Lord Chancellor, the Earl Marshall, a principal Secretary of State, the Archbishop of Canterbury or the Bishop of London. This law finally expired in 1695.[16]

Other senses

In commercial printing, the term is used, in line with the meaning of the Latin word, of final approval by a customer or his agent, perhaps after review of a test printing, for carrying out the printing job.

As a metaphor, the word "imprimatur" is used loosely of any form of approval or endorsement, especially by an official body or a person of importance,[1] as in the newspaper headline, "Protection of sources now has courts' imprimatur",[17] but also much more vaguely, and probably incorrectly, as in "Children, the final imprimatur to family life, are being borrowed, adopted, created by artificial insemination."[18]

Judaism

Haskama, approval, הַסְכָּמָה is a rabbinic approval of a religious book concerning Judaism. It is written by a prominent rabbi in his own name, not in the name of a religious organization or hierarchy.

Similar terms

- Digital imprimatur is a hypothetical system of internet censorship.

- Imprimatur is also the name of a 2002 thriller novel by Rita Monaldi and Francesco Sorti, with the castrato singer Atto Melani as a central character.

- In painting, the distinct term "imprimatura" is used of an underlying coat of paint.

- In the Doctor Who Doctor Who Virgin New Adventures book series, the Rassilonian Imprimatur is the equivalent of a university degree, given to Time Lords upon the conclusion of their education.

References

- 1 2 "Word of the Day: imprimatur". Dictionary.reference.com. 2004-08-19. Retrieved 2013-01-22.

- 1 2 "Code of Canon Law, canon 830 §3". Intratext.com. 2007-05-04. Retrieved 2013-01-22.

- ↑ The America Heritage Dictionary, retrieved 2009-07-30

- 1 2 3 "Code of Canon Law - IntraText". vatican.va.

- ↑ "Office of the Bishop (Diocese of St. Petersburg) at 6363 9th Avenue North, Saint Petersburg, FL 33710 US - Office of Censor Librorum". catholicweb.com.

- ↑ "Encyclopaedia Britannica: ''imprimatur''". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2013-01-22.

- ↑ An example of such a declaration. Books.google.ie. Retrieved 2013-01-22.

- 1 2 "Code of Canon Law, canon 824". Intratext.com. 2007-05-04. Retrieved 2013-01-22.

- 1 2 "Catholic Encyclopedia: ''Censorship of Books". Newadvent.org. Retrieved 2013-01-22.

- ↑ National Catholic Reporter, 27 February 1998: Vatican orders bishop to remove imprimatur,

- ↑ "Code of Canon Law, canon 826 §3". Intratext.com. 2007-05-04. Retrieved 2013-01-22.

- ↑ "Code of Canon Law, canon 827 §1". Intratext.com. 2007-05-04. Retrieved 2013-01-22.

- ↑ "Code of Canon Law, canon 827 §2". Intratext.com. 2007-05-04. Retrieved 2013-01-22.

- ↑ "Code of Canon Law, canon 827 §3". Intratext.com. 2007-05-04. Retrieved 2013-01-22.

- ↑ "iPhone Confession App Receives Imprimatur". Zenit. 2011-02-02. Retrieved 2013-01-22.

- ↑ The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford University Press 2005 ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3), article imprimatur

- ↑ "Irish Times, 15 February 2010, retrieved 27 February 2010". Irishtimes.com. 2010-02-02. Retrieved 2013-01-22.

- ↑ Hall, Richard (1988-06-19). "New York Times, 19 June 1988, retrieved 27 February 2010". New York Times. Retrieved 2013-01-22.