Impedance bridging

In electronics, especially audio and sound recording, a high impedance bridging, voltage bridging, or simply bridging connection is one in which the load impedance is much larger than the source impedance.[1][2][3] In cases where only the load impedance can be varied, maximizing the load impedance serves to both minimize the current drawn by the load and maximize the voltage signal across load. Essentially, the load is measuring the source's voltage without affecting it. In cases where only the source impedance can be varied, minimizing the source impedance serves to maximize the power delivered to the load. A different configuration is an impedance matching connection in which the source and load impedances are either equal or complex conjugates. Such a configuration serves to either prevent reflections when transmission lines are involved, or to maximize power delivered to the load given an unchangeable source impedance.

Explanation

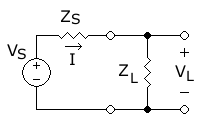

When the output of a device (consisting of the voltage source VS and output impedance ZS in illustration) is connected to the input of another device (the load impedance ZL in the illustration), it is a bridging connection if the input impedance of the load device is much greater than (typically at least ten times) the output impedance of the source device.

Given an unchangeable ZS, one can maximize the voltage across ZL by making ZL as large as possible. This also correspondingly minimizes the current drawn from the source device. This has a number of effects including:

- Increased signal level (when the signal in question is completely described by the voltage, as often is the case with audio)

- Reduced distortion due to the source having to output less current

- Possibly increased environmental noise pickup (since the combined parallel impedance of ZS and ZL increases slightly and makes it easier for stray noise to drive the signal node). (The impedance will be dominated by the source, though, which is still small in a bridging connection.)

This situation is typically encountered in line or mic level connections where the source device (such as the line-out of an audio player or the output of a microphone) has a fixed output impedance which cannot be changed. In such cases, maximum signal level with minimum distortion is obtained with a receiving device that has as high an input impedance as possible (not considering noise).

In the cases of devices with very high output impedances, such as with a guitar or a high-Z mic, a DI box can be used to convert the high output impedances to a lower impedance so as to not require the receiving device to have outrageously high input impedance and thus suffer drawbacks such as increased noise pickup with long cable runs. In such cases, the DI box is placed close to the source device (such as the guitar and mic), and any long cables are attached to the output of the DI box (which usually also converts unbalanced signals to balanced signals to further increase noise immunity).

Given an unchangeable ZL, one can maximize both the voltage and current (and therefore, the power) at the load by minimizing ZS. This is because the power delivered to the load in the above circuit (assuming all impedances are purely real) is:

As can be seen, to maximize PL, one needs to minimize RS.

This situation is mostly encountered in the interface between an audio amplifier and a loudspeaker. In such cases, the impedance of the loudspeaker is fixed (a typical value being 8Ω), so to deliver the maximum power to the speaker, the output impedance of the amplifier should be as small as possible (ideally zero). Again, this is for a case where ZL cannot be changed while ZS can be freely changed. In tube amplifiers where ZS is high by nature, maximum power delivery to the speaker (a much lower impedance) is achieved through a transformer that matches the high output impedance of the tube amp to the lower impedance of the speaker.

Maximizing power transfer given a fixed source impedance

A related case, but one which does not occur often in audio, is to optimize the power delivered to the load when the source impedance is unchangeable. In such cases, power delivery is maximized when the load impedance is matched to the source. (See Maximum power transfer theorem.) The only typical audio application where power delivery (as opposed to voltage delivery) is important is the situation mentioned above of an amplifier driving a loudspeaker. A loudspeaker's impedance is a function of its various electrical and mechanical characteristics, and this impedance typically takes on a value between 2 and 16 ohms without much room for variation. It is however, relatively easy these days to design an audio amplifier with any of a range of output impedances, even down to nearly zero. In a hypothetical situation with an amplifier having an output impedance much higher than zero, say 8Ω, then it is true that maximum power will be delivered if the loudspeaker also has an 8Ω impedance. .This is assuming that the amplifier is modeled by VS and ZS as shown above, and that the VS between the two example amplifiers have the same value.

The matched impedance situation is encountered much more in non-audio-related situations, for example in antenna design where the impedance at the antenna terminals takes on a set value due to requirements in its geometry. In such cases, the impedance of the circuit stage connected to the antenna should be matched to the antenna terminal impedance in order to maximize power transfer. Such cases frequently arise in RF circuits, where transmission line effects also dictate impedance matching.

Audio amplifiers

In audio amplifier specifications, the input impedance of modern op-amp circuits (and many old vacuum tube circuits) is often naturally much higher than the signal source. The value of the output impedance is also usually desired to be significantly lower than the load impedance. When driving transducers (especially loudspeakers) the output impedance is often described by a ratio, the damping factor, DF, which is:

Here, Zsource is the output impedance of the amplifier. Knowing the DF, one can easily calculate Zsource:

Zload is the impedance of a loudspeaker, usually around 8Ω nominally. The output impedance of the amplifier is typically in the same order of magnitude as the impedance of the cables connecting it to the speaker (<0.1Ω), so DF can be rather high, ranging into the hundreds. While voltage-drives to speakers (reducing back-EMF from the speaker), i.e. high damping factors, are generally taken as a good design goal, there are some engineers who advocate low-nfb power amplifiers with damping factors closer to unity[4] or find high Damping Factors have little effect,[5] such as a mere 0.35 dB difference in real-life results between a high (100) and medium (20) Damping Factor.[6]

External links

- Impedance Matching – explains that impedance matching of the amplifier to the loudspeaker is no longer considered best practice, because modern amplifiers are "active control devices"

- 8 Ohm Output and 150 Ohm Input - What is that?

- Bruce Bartlett, IMPEDANCE FAQ

References

- ↑ Eargle, John; Foreman, Chris (2002-01-01). Audio Engineering for Sound Reinforcement. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 9780634043550.

In all modern usage the microphone looks into an impedance in the 2000 ohm range or higher, and this represents what is called a bridging load, one which is effectively an open circuit load for the microphone.

- ↑ Davis, Gary D.; Jones, Ralph (1989-01-01). The Sound Reinforcement Handbook. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 9780881889000.

A circuit where the input termination impedance is a minimum of some 10 times the source impedance of the output driving that input is said to be a bridging input

- ↑ Holman, Tomlinson (2012-11-12). Sound for Film and Television. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781136046094.

In the case of bridging systems, we say the source impedance is low and the load impedances are high

- ↑ Pass, Nelson. "1 Current Source Amplifiers and Sensitive / Full-Range Drivers" (PDF). Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ↑ Elliott, Rod (20 January 2010). "Impedance, and how it affects audio equipment". ESP. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ↑ "Damping factor". Retrieved 15 February 2016.