Immigration

| Legal status of persons |

|---|

| Concepts |

| Designations |

| Social politics |

Immigration is the international movement of people into a destination country of which they are not natives or where they do not possess citizenship in order to settle or reside there, especially as permanent residents or naturalized citizens, or to take-up employment as a migrant worker or temporarily as a foreign worker.[1][2][3]

When people cross national borders during their migration, they are called migrants or immigrants (from Latin: migrare, wanderer) from the perspective of the country which they enter. From the perspective of the country which they leave, they are called emigrant or outmigrant.[4] Sociology designates immigration usually as migration (as well as emigration accordingly outward migration).

Immigrants are motivated to leave their former countries of citizenship, or habitual residence, for a variety of reasons, including a lack of local access to resources, a desire for economic prosperity, to find or engage in paid work, to better their standard of living, family reunification, retirement, climate or environmentally induced migration, exile, escape from prejudice, conflict or natural disaster, or simply the wish to change one's quality of life. Commuters, tourists and other short-term stays in a destination country do not fall under the definition of immigration or migration, seasonal labour immigration is sometimes included.

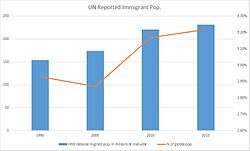

In 2013 the United Nations estimated that there were 231,522,215 immigrants in the world (apx. 3.25% of the global population).[5] The United Arab Emirates has the largest proportion of immigrants in the world, followed by Qatar.[6][7]

History

Many animals have migrated across evolutionary history (not including seasonal bird migration), including pre-humans. Human migration started with the migration out of Africa into the Middle East, and then to Asia, Australia, Europe, Russia, and the Americas. This is discussed in the article pre-modern human migration.

Recent history is discussed in the articles history of human migration and human migration.

Statistics

As of 2015, the number of international migrants has reached 244 million worldwide, which reflects a 41% increase since 2000. One third of the world's international migrants are living in just 20 countries. The largest number of international migrants live in the United States, with 19% of the world's total. Germany and Russia host 12 million migrants each, taking the second and third place in countries with the most migrants worldwide. Saudi Arabia hosts 10 million migrants, followed by the United Kingdom (9 million) and the United Arab Emirates (8 million).[8]

Between 2000 and 2015, Asia added more international migrants than any other major area in the world, gaining 26 million. Europe added the second largest with about 20 million. In most parts of the world, migration occurs between countries that are located within the same major area.[8]

In 2015, the number of international migrants below the age of 20 reached 37 million, while 177 million are between the ages of 20 and 64. International migrants living in Africa were the youngest, with a median age of 29, followed by Asia (35 years), and Latin America/Caribbean (36 years), while migrants were older in Northern America (42 years), Europe (43 years), and Oceania (44 years).[8]

Nearly half (43%) of all international migrants originate in Asia, and Europe was the birthplace of the second largest number of migrants (25%), followed by Latin America (15%). India has the largest diaspora in the world (16 million people), followed by Mexico (12 million) and Russia (11 million).[8]

2012 survey

A 2012 survey by Gallup found that given the opportunity, 640 million adults would migrate to another country, with 23% of these would-be immigrant choosing the United States as their desired future residence, while 7% of respondents, representing 45 million people, would choose the United Kingdom. The other top desired destination countries (those where an estimated 69 million or more adults would like to go) were Canada, France, Saudi Arabia, Australia, Germany and Spain.[9]

Understanding of immigration

One theory of immigration distinguishes between push and pull factors.[13]

Push factors refer primarily to the motive for immigration from the country of origin. In the case of economic migration (usually labor migration), differentials in wage rates are common. If the value of wages in the new country surpasses the value of wages in one's native country, he or she may choose to migrate, as long as the costs are not too high. Particularly in the 19th century, economic expansion of the US increased immigrant flow, and nearly 15% of the population was foreign born,[14] thus making up a significant amount of the labor force.

As transportation technology improved, travel time and costs decreased dramatically between the 18th and early 20th century. Travel across the Atlantic used to take up to 5 weeks in the 18th century, but around the time of the 20th century it took a mere 8 days.[15] When the opportunity cost is lower, the immigration rates tend to be higher.[15] Escape from poverty (personal or for relatives staying behind) is a traditional push factor, and the availability of jobs is the related pull factor. Natural disasters can amplify poverty-driven migration flows. Research shows that for middle-income countries, higher temperatures increase emigration rates to urban areas and to other countries. For low-income countries, higher temperatures reduce emigration.[16]

Emigration and immigration are sometimes mandatory in a contract of employment: religious missionaries and employees of transnational corporations, international non-governmental organizations, and the diplomatic service expect, by definition, to work "overseas". They are often referred to as "expatriates", and their conditions of employment are typically equal to or better than those applying in the host country (for similar work).[17]

For some migrants, education is the primary pull factor (although most international students are not classified as immigrants). Retirement migration from rich countries to lower-cost countries with better climate is a new type of international migration. Examples include immigration of retired British citizens to Spain or Italy and of retired Canadian citizens to the US (mainly to the US states of Florida and Texas).[17]

Non-economic push factors include persecution (religious and otherwise), frequent abuse, bullying, oppression, ethnic cleansing, genocide, risks to civilians during war, and social marginalization.[18][19] Political motives traditionally motivate refugee flows; for instance, people may emigrate in order to escape a dictatorship.[20]

Some migration is for personal reasons, based on a relationship (e.g. to be with family or a partner), such as in family reunification or transnational marriage (especially in the instance of a gender imbalance). Recent research has found gender, age, and cross-cultural differences in the ownership of the idea to immigrate.[21] In a few cases, an individual may wish to immigrate to a new country in a form of transferred patriotism. Evasion of criminal justice (e.g., avoiding arrest) is a personal motivation. This type of emigration and immigration is not normally legal, if a crime is internationally recognized, although criminals may disguise their identities or find other loopholes to evade detection. For example, there have been reports of war criminals disguising themselves as victims of war or conflict and then pursuing asylum in a different country.[22][23][24]

Barriers to immigration come not only in legal form or political form; natural and social barriers to immigration can also be very powerful. Immigrants when leaving their country also leave everything familiar: their family, friends, support network, and culture. They also need to liquidate their assets, and they incur the expense of moving. When they arrive in a new country, this is often with many uncertainties including finding work, where to live, new laws, new cultural norms, language or accent issues, possible racism, and other exclusionary behavior towards them and their family.[25][26]

The politics of immigration have become increasingly associated with other issues, such as national security and terrorism, especially in western Europe, with the presence of Islam as a new major religion. Those with security concerns cite the 2005 French riots and point to the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy as examples of the value conflicts arising from immigration of Muslims in Western Europe. Because of all these associations, immigration has become an emotional political issue in many European nations.[28][29]

Studies have suggested that some special interest groups lobby for less immigration for their own group and more immigration for other groups since they see effects of immigration, such as increased labor competition, as detrimental when affecting their own group but beneficial when impacting other groups. A 2010 European study suggested that "employers are more likely to be pro-immigration than employees, provided that immigrants are thought to compete with employees who are already in the country. Or else, when immigrants are thought to compete with employers rather than employees, employers are more likely to be anti-immigration than employees."[30] A 2011 study examining the voting of US representatives on migration policy suggests that "representatives from more skilled labor abundant districts are more likely to support an open immigration policy towards the unskilled, whereas the opposite is true for representatives from more unskilled labor abundant districts."[31]

Another contributing factor may be lobbying by earlier immigrants. The Chairman for the US Irish Lobby for Immigration Reform—which lobby for more permissive rules for immigrants, as well as special arrangements just for Irish people—has stated that "the Irish Lobby will push for any special arrangement it can get—'as will every other ethnic group in the country.'"[32][33]

Economic migrant

The term economic migrant refers to someone who has travelled from one region to another region for the purposes of seeking employment and an improvement in quality of life and access to resources. An economic migrant is distinct from someone who is a refugee fleeing persecution.

Many countries have immigration and visa restrictions that prohibit a person entering the country for the purposes of gaining work without a valid work visa. As a violation of a State's immigration laws a person who is declared to be an economic migrant can be refused entry into a country.

The process of allowing immigrants into a particular country is believed to have effects on wages and employment. In particular lower skilled workers are thought to be directly affected by economic migrants, but evidence suggests that this is due to adjustments within industries.[34]

The World Bank estimates that remittances totaled $420 billion in 2009, of which $317 billion went to developing countries.[35]

Laws and ethics

Treatment of migrants in host countries, both by governments, employers, and original population, is a topic of continual debate and criticism, and the violation of migrant human rights is an ongoing crisis.[36] The United Nations Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families, has been ratified by 48 states, most of which are heavy exporters of cheap labor. Major migrant-receiving countries and regions - including Western Europe, North America, Pacific Asia, Australia, and the Gulf States - have not ratified the Convention, even though they are host to the majority of international migrant workers.[37][38] Although freedom of movement is often recognized as a civil right in many documents such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966), the freedom only applies to movement within national borders and the ability to return to one's home state.[39][40]

Some proponents of immigration argue that the freedom of movement both within and between countries is a basic human right, and that the restrictive immigration policies, typical of nation-states, violate this human right of freedom of movement.[41] Such arguments are common among anti-state ideologies like anarchism and libertarianism.[42] As philosopher and Open borders activist Jacob Appel has written, "Treating human beings differently, simply because they were born on the opposite side of a national boundary, is hard to justify under any mainstream philosophical, religious or ethical theory."[43]

Where immigration is permitted, it is typically selective. As of 2003, family reunification accounted for approximately two-thirds of legal immigration to the US every year.[44] Ethnic selection, such as the White Australia policy, has generally disappeared, but priority is usually given to the educated, skilled, and wealthy. Less privileged individuals, including the mass of poor people in low-income countries, cannot avail themselves of the legal and protected immigration opportunities offered by wealthy states. This inequality has also been criticized as conflicting with the principle of equal opportunities. The fact that the door is closed for the unskilled, while at the same time many developed countries have a huge demand for unskilled labor, is a major factor in illegal immigration. The contradictory nature of this policy—which specifically disadvantages the unskilled immigrants while exploiting their labor—has also been criticized on ethical grounds.

Immigration policies which selectively grant freedom of movement to targeted individuals are intended to produce a net economic gain for the host country. They can also mean net loss for a poor donor country through the loss of the educated minority—a "brain drain". This can exacerbate the global inequality in standards of living that provided the motivation for the individual to migrate in the first place. One example of competition for skilled labour is active recruitment of health workers from developing countries by developed countries.[45][46] There may however also be a "brain gain" to emigration, as migration opportunities lead to greater investments in education in developing countries.[47][48][49][50] Overall, research suggests that migration is beneficial both to the receiving and sending countries.[51]

Economic effects

A survey of leading economists shows a consensus behind the view that high-skilled immigration makes the average American better off.[52] A survey of the same economists also shows strong support behind the notion that low-skilled immigration makes the average American better off.[53] According to David Card, Christian Dustmann, and Ian Preston, "most existing studies of the economic impacts of immigration suggest these impacts are small, and on average benefit the native population".[54] In a survey of the existing literature, Örn B Bodvarsson and Hendrik Van den Berg write, "a comparison of the evidence from all the studies... makes it clear that, with very few exceptions, there is no strong statistical support for the view held by many members of the public, namely that immigration has an adverse effect on native-born workers in the destination country."[55]

Whereas the impact on the average native tends to be small and positive, studies show more mixed results for low-skilled natives, but whether the effects are positive or negative, they tend to be small either way.[56][57][58][59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66][67][68] Overall immigration has not had much effect on native wage inequality[69][70] but low-skill immigration has been linked to greater income equality in the native population.[71] Research also suggests that diversity has a net positive effect on productivity[72][73] and economic prosperity.[74] A 2011 literature review of the economic impacts of immigration found that the net fiscal impact of migrants varies across studies but that the most credible analyses typically find small and positive fiscal effects on average.[60] According to the authors, "the net social impact of an immigrant over his or her lifetime depends substantially and in predictable ways on the immigrant's age at arrival, education, reason for migration, and similar".[60] According to a 2007 literature review by the Congressional Budget Office, "Over the past two decades, most efforts to estimate the fiscal impact of immigration in the United States have concluded that, in aggregate and over the long term, tax revenues of all types generated by immigrants—both legal and unauthorized—exceed the cost of the services they use."[75] A 2016 study found that "the diversity of immigrants relates positively to measures of economic prosperity."[76]

Studies of refugees' impact on native welfare are scant but the existing literature shows mixed results (negative, positive and no significant effects on native welfare).[57][77][78][79][80][81][82][83][84][85][86][87] According to labor economist Giovanni Peri, the existing literature suggests that there are no economic reasons why the American labor market could not easily absorb 100,000 Syrian refugees in a year.[88] Refugees integrate more slowly into host countries' labor markets than labor migrants, in part due to the loss and depreciation of human capital and credentials during the asylum procedure.[89] Refugees tend to do worse in economic terms than natives, even when they have the same skills and language proficiencies of natives. For instance, a 2013 study of Germans in West-Germany who had been displaced from Eastern Europe during and after World War II showed that the forced German migrants did far worse economically than their native West-German counterparts decades later.[90] Second-generation forced German migrants also did worse in economic terms than their native counterparts.[90]

Research on the economic effects of undocumented immigrants is even more scant but existing studies suggests that the effects are positive for the native population,[91][92] and public coffers.[75] A 2015 study shows that "increasing deportation rates and tightening border control weakens low-skilled labor markets, increasing unemployment of native low-skilled workers. Legalization, instead, decreases the unemployment rate of low-skilled natives and increases income per native."[59] Studies show that legalization of undocumented immigrants would boost the U.S. economy; a 2013 study found that granting legal status to undocumented immigrants would raise their incomes by a quarter (increasing U.S. GDP by approximately $1.4 trillion over a ten-year period),[93] and 2016 study found that "legalization would increase the economic contribution of the unauthorized population by about 20%, to 3.6% of private-sector GDP."[94]

Research suggests that migration is beneficial both to the receiving and sending countries.[51][95] According to one study, welfare increases in both types of countries: "welfare impact of observed levels of migration is substantial, at about 5% to 10% for the main receiving countries and about 10% in countries with large incoming remittances".[51] According to Branko Milanovic, country of residency is by far the most important determinant of global income inequality, which suggests that the reduction in labor barriers would significantly reduce global income inequality.[96][97] A study of equivalent workers in the United States and 42 developing countries found that "median wage gap for a male, unskilled (9 years of schooling), 35 year-old, urban formal sector worker born and educated in a developing country is P$15,400 per year at purchasing power parity".[98] A 2014 survey of the existing literature on emigration finds that a 10 percent emigrant supply shock would increase wages in the sending country by 2-5.5%.[99] According to economists Michael Clemens and Lant Pratchett, "permitting people to move from low-productivity places to high-productivity places appears to be by far the most efficient generalized policy tool, at the margin, for poverty reduction".[100] A successful two-year in situ anti-poverty program, for instance, helps poor people make in a year what is the equivalent of working one day in the developed world.[100] Research on a migration lottery that allowed that allowed Tongans to move to New Zealand found that the lottery winners saw a 263% increase in income from migrating (after only one year in New Zealand) relative to the unsuccessful lottery entrants.[101] A longer-term study on the Tongan lottery winners finds that they "continue to earn almost 300 percent more than non-migrants, have better mental health, live in households with more than 250 percent higher expenditure, own more vehicles, and have more durable assets".[102] A conservative estimate of their lifetime gain to migration is NZ$315,000 in net present value terms (approximately US$237,000).[102] A slight reduction in the barriers to labor mobility between the developing and developed world would do more to reduce poverty in the developing world than any remaining trade liberalization.[103]

Studies show that the elimination of barriers to migration would have profound effects on world GDP, with estimates of gains ranging between 67–147.3%.[104][105][106] Research also finds that migration leads to greater trade in goods and services.[107][108][109][110] Using 130 years of data on historical migrations to the United States, one study finds "that a doubling of the number of residents with ancestry from a given foreign country relative to the mean increases by 4.2 percentage points the probability that at least one local firm invests in that country, and increases by 31% the number of employees at domestic recipients of FDI from that country. The size of these effects increases with the ethnic diversity of the local population, the geographic distance to the origin country, and the ethno-linguistic fractionalization of the origin country."[111] Another study, looking at the period 1960-2013, finds that immigration and cultural diversity boost economic development.[112][113]

According to one survey of the existing economic literature, "much of the existing research points towards positive net contributions by immigrant entrepreneurs."[114] Immigrants to the United States create businesses at higher rates than natives.[115] Mass migration can also boost innovation and growth, as shown by the Huguenot Diaspora in Prussia,[116] German Jewish Émigrés in the US,[117] the Mariel boatlift[118] and west-east migration in the wake of German reunification.[119] Immigrants have been linked to greater invention and innovation in the US.[120] According to one report, "immigrants have started more than half (44 of 87) of America’s startup companies valued at $1 billion dollars or more and are key members of management or product development teams in over 70 percent (62 of 87) of these companies."[121] Research also shows that labor migration increases human capital.[122][123][124][125][126] Foreign doctoral students are a major source of innovation in the American economy.[127] In the United States, immigrant workers hold a disproportionate share of jobs in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM): "In 2013, foreign-born workers accounted for 19.2 percent of STEM workers with a bachelor's degree, 40.7 percent of those with a master's degree, and more than half—54.5 percent—of those with a Ph.D."[128]

A 2015 study finds "some evidence that larger immigrant population shares (or inflows) yield positive impacts on institutional quality. At a minimum, our results indicate that no negative impact on economic freedom is associated with more immigration."[129] Another study, looking at the increase in Israel's population in the 1990s due to the unrestricted immigration of Jews from the Soviet Union, finds that the mass immigration did not undermine political institutions, and substantially increased the quality of economic institutions.[130]

Research indicates that immigrants are more likely to work in risky jobs than U.S.-born workers, partly due to differences in average characteristics, such as immigrants' lower English language ability and educational attainment.[131] Further, some studies indicate that higher ethnic concentration in metropolitan areas is positively related to the probability of self-employment of immigrants.[132]

Welfare

Some research has found that as immigration and ethnic heterogeneity increase, government funding of welfare and public support for welfare decrease.[133][134] Ethnic nepotism may be an explanation for this phenomenon. Other possible explanations include theories regarding in-group and out-group effects and reciprocal altruism.[135]

Research however also challenges the notion that ethnic heterogeneity reduces public goods provision.[136][137] Studies that find a negative relationship between ethnic diversity and public goods provision often fail to take into account that strong states were better at assimilating minorities, thus decreasing diversity in the long run.[136] Ethnically diverse states today consequently tend to be weaker states.[136] Because most of the evidence on fractionalization comes from sub-Saharan Africa and the United States, the generalizability of the findings is questionable.[137]

Research finds that Americans' attitudes towards immigration influence their attitudes towards welfare spending.[138]

Education

One study finds that non-native speakers of English in the UK have no causal impact on the performance of other pupils.[139] The presence of immigrant children in classrooms has no significant impact on the test scores of Dutch children.[140] An Austrian study finds no effect on grade repetition among native students exposed to migrant students.[141] A North Carolina study found that the presence of Latin American children in schools had no significant negative effects on peers, but that students with limited English skills had slight negative effects on peers.[142]

Assimilation

A 2015 report by the National Institute of Demographic Studies finds that an overwhelming majority of second-generation immigrants of all origins in France feel French, despite the persistent discrimination in education, housing and employment that many of the minorities face.[143]

A 2016 paper challenges the view that cultural differences are necessarily an obstacle to long-run economic performance of migrants. It finds that "first generation migrants seem to be less likely to success the more culturally distant they are, but this effect vanishes as time spent in the USA increases."[144]

Research shows that country of origin matters for speed and depth of immigrant assimilation but that there is considerable assimilation overall.[145] Research finds that first generation immigrants from countries with less egalitarian gender cultures adopt gender values more similar to natives over time.[146][147] According to one study, "this acculturation process is almost completed within one generational succession: The gender attitudes of second generation immigrants are difficult to distinguish from the attitudes of members of mainstream society. This holds also for children born to immigrants from very gender traditional cultures and for children born to less well integrated immigrant families."[146] Similar results are found on a study of Turkish migrants to Western Europe.[147] The assimilation on gender attitudes has been observed in education, as one study finds "that the female advantage in education observed among the majority population is usually present among second-generation immigrants."[148]

First-generation immigrants tend to hold less accepting views of homosexual lifestyles but opposition weakens with longer stays.[149] Second-generation immigrants are overall more accepting of homosexual lifestyles, but the acculturation effect is weaker for Muslims and to some extent, Eastern Orthodox migrants.[149]

A study of Bangladeshi migrants in East London found they shifted towards the thinking styles of the wider non-migrant population in just a single generation.[150]

A study on Germany found that foreign-born parents are more likely to integrate if their children are entitled to German citizenship at birth.[151] Naturalization is associated with large and persistent wage gains for the naturalized citizens in most countries.[152]

Measuring assimilation can be difficult due to "ethnic attrition", which refers to when ancestors of migrants cease to self-identify with the nationality or ethnicity of their ancestors. This means that successful cases of assimilation will be underestimated. Research shows that ethnic attrition is sizable in Hispanic and Asian immigrant groups in the United States.[153][154] By taking account of ethnic attrition, the assimilation rate of Hispanics in the United States improves significantly.[153][155]

Studies on programs that randomly allocate refugee immigrants across municipalities find that the assignment of neighborhood impacts immigrant crime propensity, education and earnings.[156][157][158][159][160]

Research suggests that bilingual schooling reduces barriers between speakers from two different communities.[161]

Social capital

There is some research that suggests that immigration adversely affects social capital.[162] One study, for instance, found that "larger increases in US states' Mexican population shares correspond to larger decreases in social capital over the period" 1986-2004.[163]

Health

Research suggests that immigration has positive effects on native workers' health.[164] As immigration rises, native workers are pushed into less demanding jobs, which improves native workers' health outcomes.[164]

Crime

Much of the empirical research on the causal relationship between immigration and crime has been limited due to weak instruments for determining causality.[165] According to one economist writing in 2014, "while there have been many papers that document various correlations between immigrants and crime for a range of countries and time periods, most do not seriously address the issue of causality."[166] The problem with causality primarily revolves around the location of immigrants being endogenous, which means that immigrants tend to disproportionally locate in deprived areas where crime is higher (because they cannot afford to stay in more expensive areas) or because they tend to locate in areas where there is a large population of residents of the same ethnic background.[167] A burgeoning literature relying on strong instruments provides mixed findings.[167][168][169][170][171][172][173][174] As one economist describes the existing literature in 2014, "most research for the US indicates that if any, this association is negative... while the results for Europe are mixed for property crime but no association is found for violent crime".[167] Another economist writing in 2014, describes how "the evidence, based on empirical studies of many countries, indicates that there is no simple link between immigration and crime, but legalizing the status of immigrants has beneficial effects on crime rates."[166]

The relationship between crime and the legal status of immigrants remains understudied[175] but studies on amnesty programs in the United States and Italy suggest that legal status can largely explain the differences in crime between legal and illegal immigrants, most likely because legal status leads to greater job market opportunities for the immigrants.[166][176][177][178][179] However, one study finds that the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) of 1986 led to an increase in crime among previously undocumented immigrants.[180]

Discrimination

Europe

Research suggests that police practices, such as racial profiling, over-policing in areas populated by minorities and in-group bias may result in disproportionately high numbers of racial minorities among crime suspects in Sweden, Italy, and England and Wales.[181][182][183][184][185] Research also suggests that there may be possible discrimination by the judicial system, which contributes to a higher number of convictions for racial minorities in Sweden, the Netherlands, Italy, Germany, Denmark and France.[181][183][184][186][187][188][189]

Several meta-analyses find extensive evidence of ethnic and racial discrimination in hiring in the North-American and European labor markets.[190][191][192] A 2016 meta-analysis of 738 correspondence tests in 43 separate studies conducted in OECD countries between 1990 and 2015 finds that there is extensive racial discrimination in hiring decisions in Europe and North-America.[191] Equivalent minority candidates need to send around 50% more applications to be invited for an interview than majority candidates.[191]

A 2014 meta-analysis found extensive evidence of racial and ethnic discrimination in the housing market of several European countries.[190]

The United States

Business

A 2014 meta-analysis of racial discrimination in product markets found extensive evidence of minority applicants being quoted higher prices for products.[190] A 1995 study found that car dealers "quoted significantly lower prices to white males than to black or female test buyers using identical, scripted bargaining strategies."[193] A 2013 study found that eBay sellers of iPods received 21 percent more offers if a white hand held the iPod in the photo than a black hand.[194]

Criminal justice system

Research suggests that police practices, such as racial profiling, over-policing in areas populated by minorities and in-group bias may result in disproportionately high numbers of racial minorities among crime suspects.[195][196][197][198] Research also suggests that there may be possible discrimination by the judicial system, which contributes to a higher number of convictions for racial minorities.[199][200][201][202][203] A 2012 study found that "(i) juries formed from all-white jury pools convict black defendants significantly (16 percentage points) more often than white defendants, and (ii) this gap in conviction rates is entirely eliminated when the jury pool includes at least one black member."[201] Research has found evidence of in-group bias, where "black (white) juveniles who are randomly assigned to black (white) judges are more likely to get incarcerated (as opposed to being placed on probation), and they receive longer sentences."[203] In-group bias has also been observed when it comes to traffic citations, as black and white cops are more likely to cite out-groups.[197]

Education

A 2015 study using correspondence tests "found that when considering requests from prospective students seeking mentoring in the future, faculty were significantly more responsive to White males than to all other categories of students, collectively, particularly in higher-paying disciplines and private institutions."[204] Through affirmative action, there is reason to believe that elite colleges favor minority applicants.[205]

Housing

A 2014 meta-analysis found extensive evidence of racial discrimination in the American housing market.[190] Minority applicants for housing needed to make many more enquiries to view properties.[190] Geographical steering of African-Americans in US housing remained significant.[190] A 2003 study finds "evidence that agents interpret an initial housing request as an indication of a customer's preferences, but also are more likely to withhold a house from all customers when it is in an integrated suburban neighborhood (redlining). Moreover, agents' marketing efforts increase with asking price for white, but not for black, customers; blacks are more likely than whites to see houses in suburban, integrated areas (steering); and the houses agents show are more likely to deviate from the initial request when the customer is black than when the customer is white. These three findings are consistent with the possibility that agents act upon the belief that some types of transactions are relatively unlikely for black customers (statistical discrimination)."[206]

A report by the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development where the department sent African-Americans and whites to look at apartments found that African-Americans were shown fewer apartments to rent and houses for sale.[207]

Labor market

Several meta-analyses find extensive evidence of ethnic and racial discrimination in hiring in the American labor market.[190][192][208] A 2016 meta-analysis of 738 correspondence tests - tests where identical CVs for stereotypically black and white names were sent to employers - in 43 separate studies conducted in OECD countries between 1990 and 2015 finds that there is extensive racial discrimination in hiring decisions in Europe and North-America.[208] These correspondence tests showed that equivalent minority candidates need to send around 50% more applications to be invited for an interview than majority candidates.[208][209] A study that examine the job applications of actual people provided with identical résumés and similar interview training showed that African-American applicants with no criminal record were offered jobs at a rate as low as white applicants who had criminal records.[210]

Impact on the sending country

Remittances increase living standards in the country of origin. Remittances are a large share of the GDP of many developing countries.[211][211] A study on remittances to Mexico found that remittances lead to a substantial increase in the availability of public services in Mexico, surpassing government spending in some localities.[212]

Research finds that emigration and low migration barriers has net positive effects on human capital formation in the sending countries.[47][48][49][50] This means that there is a "brain gain" instead of a "brain drain" to emigration.

One study finds that sending countries benefit indirectly in the long-run on the emigration of skilled workers because those skilled workers are able to innovate more in developed countries, which the sending countries are able to benefit on as a positive externality. Greater emigration of skilled workers consequently leads to greater economic growth and welfare improvements in the long-run.[213] The negative effects of high-skill emigration remain largely unfounded. According to economist Michael Clemens, it has not been shown that restrictions on high-skill emigration reduce shortages in the countries of origin.[214]

Research also suggests that emigration, remittances and return migration can have a positive impact on political institutions and democratization in the country of origin.[215][216][217][218][219][220][221][222] Research also shows that remittances can lower the risk of civil war in the country of origin.[223] Return migration from countries with liberal gender norms has been associated with the transfer of liberal gender norms to the home country.[224]

Research suggests that emigration causes an increase in the wages of those who remain in the country of origin. A 2014 survey of the existing literature on emigration finds that a 10 percent emigrant supply shock would increase wages in the sending country by 2-5.5%.[225] A study of emigration from Poland shows that it led to a slight increase in wages for high- and medium-skilled workers for remaining Poles.[226] A 2013 study finds that emigration from Eastern Europe after the 2004 EU enlargement increased the wages of remaining young workers in the country of origin by 6%, while it had no effect on the wages of old workers.[227] The wages of Lithuanian men increased as a result of post-EU enlargement emigration.[228] Return migration is associated with greater household firm revenues.[229]

Some research shows that the remittance effect is not strong enough to make the remaining natives in countries with high emigration flows better off.[230]

It has been argued that high-skill emigration causes labor shortages in the country of origin. This remains unsupported in the academic literature though. According to economist Michael Clemens, it has not been shown that restrictions on high-skill emigration reduce shortages in the countries of origin.[214]

See also

- Childhood and migration

- Criticism of multiculturalism

- Feminization of migration

- Human overpopulation

- Human migration

- Immigration and crime

- Immigration law

- Immigration reform

- Multiculturalism

- Opposition to immigration

- People smuggling

- Political demography

- Repatriation

- Replacement migration

- Right of foreigners to vote

- First world privilege

- List of countries by net migration rate

- List of sovereign states and dependent territories by population density

References

- ↑ "immigration". OxfordDictionaries.com. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ↑ "immigrate". Merriam-Webster.com. Merriam-Webster, In. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ↑ "Who's who: Definitions". London, England: Refugee Council. 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- ↑ "outmigrant". OxfordDictionaries.com. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ↑ "On the move: 232 million migrants in the world". The Guardian DataBlog. Guardian News and Media Limited. 11 September 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ↑ Smith, Lydia (14 December 2014). "International Migrants Day 2014: Five countries with the highest number of immigrants". International Business Times. IBTimes Co. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ↑ Immigration - Page 19, Nick Hunter - 2012

- 1 2 3 4 "Trends in international migration, 2015" (PDF). UN.org. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. December 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ↑ "150 Million Adults Worldwide Would Migrate to the U.S". Gallup.com. 20 April 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ↑ "Crisis Strands Vietnamese Workers in a Czech Limbo". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. 5 June 2009. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ↑ "White ethnic Britons in minority in London". Financial Times. 11 December 2012.

- ↑ Graeme Paton (1 October 2007). "One fifth of children from ethnic minorities". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 15 June 2009. Retrieved 7 June 2008.

- ↑ See the NIDI/Eurostat "push and pull study" for details and examples: Archived 9 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ York, Harlan (4 July 2015). "How Many People are Immigrants?". Harlan York and Associates. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- 1 2 Boustan, Adain May . "Fertility and Immigration." UCLA. 15 January 2009.

- ↑ Cattaneo, Cristina; Peri, Giovanni (1 October 2015). "The Migration Response to Increasing Temperatures".

- 1 2 Iravani, Mohammad Reza (August 2011). "Immigration: Problems and Prospects" (PDF). International Journal of Business and Social Science. 2 (15): 296–303. ISSN 2219-1933. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ↑ Chiswick, Barry (March 2000). "The Earnings of Male Hispanic Immigrants in the United States". Social Science Research Network (Working paper). University of Illinois at Chicago Institute for the Study of Labor. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- ↑ Kislev, Elyakim (1 June 2014). "The Effect of Minority/Majority Origins on Immigrants' Integration". Social Forces. 92 (4): 1457–1486. doi:10.1093/sf/sou016. ISSN 0037-7732.

- ↑ Borjas, George J. (1 April 1982). "The Earnings of Male Hispanic Immigrants in the United States". Industrial & Labor Relations Review. 35 (3): 343–353. doi:10.1177/001979398203500304. ISSN 0019-7939.

- ↑ Rubin, M. (2013). "'It wasn't my idea to come here!': Ownership of the idea to immigrate as a function of gender, age, and culture". International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 37, 497-501. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2013.02.001

- ↑ Haskell, Leslie (18 September 2014). "EU asylum and war criminals: No place to hide". EUobserver.com. EUobserver. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- ↑ Knight, Ben (11 April 2016). "Refugees in Germany reporting dozens of war crimes". DW.com. Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- ↑ Porter, Tom (26 February 2016). "Sweden: Syrian asylum seeker suspected of war crimes under Assad regime arrested in Stockholm". International Business Times UK. International Business Times. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- ↑ Nunez, Christina (12 December 2014). "The 7 biggest challenges facing refugees and immigrants in the US". Global Citizen. Global Poverty Project. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ↑ Djajić, Slobodan (1 September 2013). "Barriers to immigration and the dynamics of emigration". Journal of Macroeconomics. 37: 41–52. doi:10.1016/j.jmacro.2013.06.001.

- ↑ Anita Böcker (1998) Regulation of migration: international experiences. Het Spinhuis. p.218. ISBN 90-5589-095-2

- ↑ "Migration, refugees, Europe – waves of emotion". Euranet Plus inside. Euranet Plus Network. 7 May 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ↑ Nowicki, Dan. "Europe learns integration can become emotional". AZCentral.com. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ↑ Tamura, Yuji, Do Employers Support Immigration? (29 July 2010). Trinity Economics Papers No. 1107. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1021941

- ↑ Facchini, G.; Steinhardt, M. F. (2011). "What drives U.S. Immigration policy? Evidence from congressional roll call votes". Journal of Public Economics. 95 (7–8): 734. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2011.02.008.

- ↑ Bernstein, Nina (16 March 2006). "An Irish Face on the Cause of Citizenship". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ↑ National Council of La Raza, Issues and Programs » Immigration » Immigration Reform, Archived 13 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Dustmann, Christian. "Labor market effects on immigration" (PDF). Business Source Elite. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ↑ Remittance Prices Worldwide MAKING MARKETS MORE TRANSPARENT (28 April 2014). "Remittance Prices Worldwide". Remittanceprices.worldbank.org. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ↑ "Amnesty International State of the World 2015-2016". AmnestyUSA.org. Amnesty International USA. 23 February 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ↑ Truong, Thanh-Dam; Gasper, Des (7 June 2011). Transnational Migration and Human Security: The Migration-Development-Security Nexus. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9783642127571.

- ↑ "International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families". Treaties.UN.org. New York: United Nations. 18 December 1990. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ↑ "The Universal Declaration of Human Rights". UN.org. Paris: United Nations. 10 December 1948. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ↑ "International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights". OHCHR.org. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. 16 December 1966. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ↑ Theresa Hayter, Open Borders: The Case Against Immigration Controls, London: Pluto Press, 2000.

- ↑ "Anarchism and Immigration". theanarchistlibrary. 1 January 2005.

- ↑ "The Ethical Case for an Open Immigration Policy". OpposingViews.com. Render Media. 4 May 2009.

- ↑ "Family Reunification", Ramah McKay, Migration Policy Institute.

- ↑ Krotz, Larry (12 September 2012). "Poaching Foreign Doctors". The Walrus. The Walrus. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ↑ Stilwell, Barbara; Diallo, Khassoum; Zurn, Pascal; Vujicic, Marko; Adams, Orvill; Dal Poz, Mario (2004). "Migration of health-care workers from developing countries: strategic approaches to its management" (PDF). Bulletin of the World Health Organization (82): 595–600. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- 1 2 Shrestha, Slesh A. (1 April 2016). "No Man Left Behind: Effects of Emigration Prospects on Educational and Labour Outcomes of Non-migrants". The Economic Journal: n/a–n/a. doi:10.1111/ecoj.12306. ISSN 1468-0297.

- 1 2 Beine, Michel; Docquier, Fréderic; Rapoport, Hillel (1 April 2008). "Brain Drain and Human Capital Formation in Developing Countries: Winners and Losers*". The Economic Journal. 118 (528): 631–652. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0297.2008.02135.x. ISSN 1468-0297.

- 1 2 Dinkelman, Taryn; Mariotti, Martine (1 February 2016). "The Long Run Effects of Labor Migration on Human Capital Formation in Communities of Origin". National Bureau of Economic Research.

- 1 2 Batista, Catia; Lacuesta, Aitor; Vicente, Pedro C. (1 January 2012). "Testing the 'brain gain' hypothesis: Micro evidence from Cape Verde". Journal of Development Economics. 97 (1): 32–45. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2011.01.005.

- 1 2 3 di Giovanni, Julian; Levchenko, Andrei A.; Ortega, Francesc (1 February 2015). "A Global View of Cross-Border Migration". Journal of the European Economic Association. 13 (1): 168–202. doi:10.1111/jeea.12110. ISSN 1542-4774.

- ↑ "Poll Results | IGM Forum". www.igmchicago.org. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ↑ "Poll Results | IGM Forum". www.igmchicago.org. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ↑ Card, David; Dustmann, Christian; Preston, Ian (1 February 2012). "Immigration, Wages, and Compositional Amenities". Journal of the European Economic Association. 10 (1): 78–119. doi:10.1111/j.1542-4774.2011.01051.x. ISSN 1542-4774.

- ↑ Bodvarsson, Örn B; Van den Berg, Hendrik (1 January 2013). The economics of immigration: theory and policy. New York; Heidelberg [u.a.]: Springer. p. 157. ISBN 9781461421153.

- ↑ Card, David (1 January 1989). "The Impact of the Mariel Boatlift on the Miami Labor Market" (PDF). doi:10.3386/w3069.

- 1 2 Foged, Mette; Peri, Giovanni. "Immigrants' Effect on Native Workers: New Analysis on Longitudinal Data †". American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 8 (2): 1–34. doi:10.1257/app.20150114.

- ↑ Borjas, George J. (1 November 2003). "The Labor Demand Curve is Downward Sloping: Reexamining the Impact of Immigration on the Labor Market". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 118 (4): 1335–1374. doi:10.1162/003355303322552810. ISSN 0033-5533.

- 1 2 Chassamboulli, Andri; Peri, Giovanni (1 October 2015). "The labor market effects of reducing the number of illegal immigrants". Review of Economic Dynamics. 18 (4): 792–821. doi:10.1016/j.red.2015.07.005.

- 1 2 3 Kerr, Sari Pekkala; Kerr, William. "Economic Impacts of Immigration: A Survey" (PDF). doi:10.3386/w16736.

- ↑ Longhi, Simonetta; Nijkamp, Peter; Poot, Jacques (1 July 2005). "A Meta-Analytic Assessment of the Effect of Immigration on Wages". Journal of Economic Surveys. 19 (3): 451–477. doi:10.1111/j.0950-0804.2005.00255.x. ISSN 1467-6419.

- ↑ Longhi, Simonetta; Nijkamp, Peter; Poot, Jacques (1 October 2010). "Meta-Analyses of Labour-Market Impacts of Immigration: Key Conclusions and Policy Implications". Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy. 28 (5): 819–833. doi:10.1068/c09151r. ISSN 0263-774X.

- ↑ Okkerse, Liesbet (1 February 2008). "How to Measure Labour Market Effects of Immigration: A Review". Journal of Economic Surveys. 22 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6419.2007.00533.x. ISSN 1467-6419.

- ↑ Ottaviano, Gianmarco I. P.; Peri, Giovanni (2012-02-01). "Rethinking the Effect of Immigration on Wages". Journal of the European Economic Association. 10 (1): 152–197. doi:10.1111/j.1542-4774.2011.01052.x. ISSN 1542-4774.

- ↑ Battisti, Michele; Felbermayr, Gabriel; Peri, Giovanni; Poutvaara, Panu (2014-05-01). "Immigration, Search, and Redistribution: A Quantitative Assessment of Native Welfare". National Bureau of Economic Research.

- ↑ Card, David (2005-08-01). "Is the New Immigration Really So Bad?". National Bureau of Economic Research.

- ↑ Dustmann, Christian; Glitz, Albrecht; Frattini, Tommaso (2008-09-21). "The labour market impact of immigration". Oxford Review of Economic Policy. 24 (3): 477–494. doi:10.1093/oxrep/grn024. ISSN 0266-903X.

- ↑ "Migrants Bring Economic Benefits for Advanced Economies". iMFdirect - The IMF Blog. 2016-10-24. Retrieved 2016-11-21.

- ↑ Card, David (1 April 2009). "Immigration and Inequality". American Economic Review. 99 (2): 1–21. doi:10.1257/aer.99.2.1. ISSN 0002-8282.

- ↑ Green, Alan G.; Green, David A. (2016-06-01). "Immigration and the Canadian Earnings Distribution in the First Half of the Twentieth Century". The Journal of Economic History. 76 (02): 387–426. doi:10.1017/S0022050716000541. ISSN 1471-6372.

- ↑ Xu, Ping; Garand, James C.; Zhu, Ling (23 September 2015). "Imported Inequality? Immigration and Income Inequality in the American States". State Politics & Policy Quarterly: 1532440015603814. doi:10.1177/1532440015603814. ISSN 1532-4400.

- ↑ Ottaviano, Gianmarco I. P.; Peri, Giovanni (1 January 2006). "The economic value of cultural diversity: evidence from US cities". Journal of Economic Geography. 6 (1): 9–44. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbi002. ISSN 1468-2702.

- ↑ Peri, Giovanni (7 October 2010). "The Effect Of Immigration On Productivity: Evidence From U.S. States". Review of Economics and Statistics. 94 (1): 348–358. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00137. ISSN 0034-6535.

- ↑ Alesina, Alberto; Harnoss, Johann; Rapoport, Hillel (17 February 2016). "Birthplace diversity and economic prosperity". Journal of Economic Growth. 21 (2): 101–138. doi:10.1007/s10887-016-9127-6. ISSN 1381-4338.

- 1 2 "The Impact of Unauthorized Immigrants on the Budgets of State and Local Governments". 2007-12-06. Retrieved 2016-06-28.

- ↑ Alesina, Alberto; Harnoss, Johann; Rapoport, Hillel (2016-02-17). "Birthplace diversity and economic prosperity". Journal of Economic Growth. 21 (2): 101–138. doi:10.1007/s10887-016-9127-6. ISSN 1381-4338.

- ↑ "Refugee Economies: Rethinking Popular Assumptions — Refugee Studies Centre". www.rsc.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ↑ "Economic Impact of Refugees in the Cleveland Area" (PDF).

- ↑ Cortes, Kalena E. (1 March 2004). "Are Refugees Different from Economic Immigrants? Some Empirical Evidence on the Heterogeneity of Immigrant Groups in the United States". Rochester, NY.

- ↑ "Much ado about nothing? The economic impact of refugee 'invasions'". The Brookings Institution. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ↑ The Impact of Syrians Refugees on the Turkish Labor Market. Policy Research Working Papers. The World Bank. 24 August 2015. doi:10.1596/1813-9450-7402.

- ↑ Maystadt, Jean-François; Verwimp, Philip. "Winners and Losers among a Refugee-Hosting Population". Economic Development and Cultural Change. 62 (4): 769–809. doi:10.1086/676458. JSTOR 10.1086/676458.

- ↑ "Immigration and Prices: Quasi-Experimental Evidence from Syrian Refugees in Turkey" (PDF).

- ↑ Ruist, Joakim (2013). "The labor market impact of refugee immigration in Sweden 1999–2007" (PDF). SU.se (Working paper). The Stockholm University Linnaeus Center for Integration Studies. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- ↑ Fakih, Ali; Ibrahim, May (2 January 2016). "The impact of Syrian refugees on the labor market in neighboring countries: empirical evidence from Jordan". Defence and Peace Economics. 27 (1): 64–86. doi:10.1080/10242694.2015.1055936. ISSN 1024-2694.

- ↑ "What are the impacts of Syrian refugees on host community welfare in Turkey ? a subnational poverty analysis (English) | The World Bank". documents.worldbank.org. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ↑ Tumen, Semih (2016-05-01). "The Economic Impact of Syrian Refugees on Host Countries: Quasi-Experimental Evidence from Turkey". American Economic Review. 106 (5): 456–460. doi:10.1257/aer.p20161065. ISSN 0002-8282.

- ↑ "'No reasons to reject refugees' - Giovanni Peri". SoundCloud. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ↑ Bevelander, Pieter; Malmö, University of (2016-05-01). "Integrating refugees into labor markets". IZA World of Labor. doi:10.15185/izawol.269.

- 1 2 Bauer, Thomas K.; Braun, Sebastian; Kvasnicka, Michael (2013-09-01). "The Economic Integration of Forced Migrants: Evidence for Post-War Germany". The Economic Journal. 123 (571): 998–1024. doi:10.1111/ecoj.12023. ISSN 1468-0297.

- ↑ Palivos, Theodore (4 June 2008). "Welfare effects of illegal immigration". Journal of Population Economics. 22 (1): 131–144. doi:10.1007/s00148-007-0182-3. ISSN 0933-1433.

- ↑ Liu, Xiangbo (1 December 2010). "On the macroeconomic and welfare effects of illegal immigration". Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control. 34 (12): 2547–2567. doi:10.1016/j.jedc.2010.06.030.

- ↑ "The Economic Effects of Granting Legal Status and Citizenship to Undocumented Immigrants" (PDF).

- ↑ Edwards, Ryan; Ortega, Francesc (2016-11-01). "The Economic Contribution of Unauthorized Workers: An Industry Analysis". National Bureau of Economic Research.

- ↑ Andreas, Willenbockel,Dirk; Sia, Go,Delfin; Amer, Ahmed, S. (2016-04-11). "Global migration revisited : short-term pains, long-term gains, and the potential of south-south migration".

- ↑ Milanovic, Branko (7 January 2014). "Global Inequality of Opportunity: How Much of Our Income Is Determined by Where We Live?". Review of Economics and Statistics. 97 (2): 452–460. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00432. ISSN 0034-6535.

- ↑ Milanovic, Branko (20 April 2016). "There is a trade-off between citizenship and migration". Financial Times. ISSN 0307-1766. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ↑ Clemens, Michael (15 January 2009). "The Place Premium: Wage Differences for Identical Workers Across the US Border".

- ↑ "Emigration and wages in source countries: a survey of the empirical literature : International Handbook on Migration and Economic Development". www.elgaronline.com. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- 1 2 "The New Economic Case for Migration Restrictions: An Assessment". www.iza.org. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- ↑ McKenzie, David; Stillman, Steven; Gibson, John (1 June 2010). "How Important is Selection? Experimental VS. Non-Experimental Measures of the Income Gains from Migration". Journal of the European Economic Association. 8 (4): 913–945. doi:10.1111/j.1542-4774.2010.tb00544.x. ISSN 1542-4774.

- 1 2 Gibson, John; Mckenzie, David J.; Rohorua, Halahingano; Stillman, Steven (1 January 2015). "The long-term impacts of international migration : evidence from a lottery". The World Bank.

- ↑ Walmsley, Terrie L.; Winters, L. Alan (1 January 2005). "Relaxing the Restrictions on the Temporary Movement of Natural Persons: A Simulation Analysis". Journal of Economic Integration. 20 (4): 688–726. doi:10.11130/jei.2005.20.4.688. JSTOR 23000667.

- ↑ Iregui, Ana Maria (1 January 2003). "Efficiency Gains from the Elimination of Global Restrictions on Labour Mobility: An Analysis using a Multiregional CGE Model".

- ↑ Clemens, Michael A (1 August 2011). "Economics and Emigration: Trillion-Dollar Bills on the Sidewalk?". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 25 (3): 83–106. doi:10.1257/jep.25.3.83. ISSN 0895-3309.

- ↑ Hamilton, B.; Whalley, J. (1 February 1984). "Efficiency and distributional implications of global restrictions on labour mobility: calculations and policy implications". Journal of Development Economics. 14 (1-2): 61–75. doi:10.1016/0304-3878(84)90043-9. ISSN 0304-3878. PMID 12266702.

- ↑ Aner, Emilie; Graneli, Anna; Lodefolk, Magnus (14 October 2015). "Cross-border movement of persons stimulates trade". VoxEU.org. Centre for Economic Policy Research. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ Bratti, Massimiliano; Benedictis, Luca De; Santoni, Gianluca (18 April 2014). "On the pro-trade effects of immigrants". Review of World Economics. 150 (3): 557–594. doi:10.1007/s10290-014-0191-8. ISSN 1610-2878.

- ↑ Foley, C. Fritz; Kerr, William R. (2011-08-01). "Ethnic Innovation and U.S. Multinational Firm Activity". National Bureau of Economic Research.

- ↑ Dany, Bahar,; Rapoport, Hillel. "Migration, knowledge diffusion and the comparative advantage of nations".

- ↑ "Migrants, Ancestors, and Investment". NBER.

- ↑ Bove, Vincenzo; Elia, Leandro (2017-01-01). "Migration, Diversity, and Economic Growth". World Development. 89: 227–239. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.08.012.

- ↑ Bove, Vincenzo; Elia, Leandro (2016-11-16). "Cultural heterogeneity and economic development". VoxEU.org. Retrieved 2016-11-16.

- ↑ Fairlie, Robert W.; Lofstrom, Magnus (2013-01-01). "Immigration and Entrepreneurship". Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA).

- ↑ Kerr, Sari Pekkala; Kerr, William R. (2016-07-01). "Immigrant Entrepreneurship". National Bureau of Economic Research.

- ↑ Hornung, Erik. "Immigration and the Diffusion of Technology: The Huguenot Diaspora in Prussia †". American Economic Review. 104 (1): 84–122. doi:10.1257/aer.104.1.84.

- ↑ Moser, Petra; Voena, Alessandra; Waldinger, Fabian. "German Jewish Émigrés and US Invention †". American Economic Review. 104 (10): 3222–3255. doi:10.1257/aer.104.10.3222.

- ↑ Harris, Rachel Anne. "The Mariel Boatlift- A Natural Experiment in Low-Skilled Immigration and Innovation" (PDF).

- ↑ School, Harvard Kennedy. "The Workforce of Pioneer Plants". www.hks.harvard.edu. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ↑ Kerr, William R. (1 January 2010). "Breakthrough inventions and migrating clusters of innovation". Journal of Urban Economics. Special Issue: Cities and EntrepreneurshipSponsored by the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation (www.kauffman.org). 67 (1): 46–60. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2009.09.006.

- ↑ "Immigrants and Billion Dollar Startups" (PDF).

- ↑ Dinkelman, Taryn; Mariotti, Martine (1 February 2016). "The Long Run Effects of Labor Migration on Human Capital Formation in Communities of Origin". National Bureau of Economic Research.

- ↑ Shrestha, Slesh A. (2016-04-01). "No Man Left Behind: Effects of Emigration Prospects on Educational and Labour Outcomes of Non-migrants". The Economic Journal: n/a–n/a. doi:10.1111/ecoj.12306. ISSN 1468-0297.

- ↑ Beine, Michel; Docquier, Fréderic; Rapoport, Hillel (2008-04-01). "Brain Drain and Human Capital Formation in Developing Countries: Winners and Losers*". The Economic Journal. 118 (528): 631–652. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0297.2008.02135.x. ISSN 1468-0297.

- ↑ Batista, Catia; Lacuesta, Aitor; Vicente, Pedro C. (2012-01-01). "Testing the 'brain gain' hypothesis: Micro evidence from Cape Verde". Journal of Development Economics. 97 (1): 32–45. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2011.01.005.

- ↑ "Skilled Emigration and Skill Creation: A quasi-experiment - Working Paper 152". Retrieved 2016-07-03.

- ↑ Stuen, Eric T.; Mobarak, Ahmed Mushfiq; Maskus, Keith E. (1 December 2012). "Skilled Immigration and Innovation: Evidence from Enrolment Fluctuations in US Doctoral Programmes*". The Economic Journal. 122 (565): 1143–1176. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0297.2012.02543.x. ISSN 1468-0297.

- ↑ "Immigrants Play a Key Role in STEM Fields".

- ↑ Clark, J.R.; Lawson, Robert; Nowrasteh, Alex; Powell, Benjamin; Murphy, Ryan (June 2015). "Does immigration impact institutions?". Public Choice. Springer. 163 (3): 321–335. doi:10.1007/s11127-015-0254-y.

- ↑ Powell, Benjamin; Clark, J. R.; Nowrasteh, Alex (2016-11-17). "Does Mass Immigration Destroy Institutions? 1990s Israel as a Natural Experiment". Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network.

- ↑ Pia m. Orrenius, P. M.; Zavodny, M. (2009). "Do Immigrants Work in Riskier Jobs?". Demography. 46 (3): 535–551. doi:10.1353/dem.0.0064. PMC 2831347

. PMID 19771943.

. PMID 19771943. - ↑ Toussaint-Comeau, Maude (2005). "Do Enclaves Matter in Immigrants' Self-Employment Decision?" (PDF). Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago Working Paper 2005-23.

- ↑ "Fighting Poverty in the US and Europe: A World of Difference". scholar.harvard.edu. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- ↑ Schmidt-Catran, Alexander W.; Spies, Dennis C. (4 March 2016). "Immigration and Welfare Support in Germany". American Sociological Review: 0003122416633140. doi:10.1177/0003122416633140. ISSN 0003-1224.

- ↑ Freeman, G. P. (2009). "Immigration, Diversity, and Welfare Chauvinism". The Forum. 7 (3). doi:10.2202/1540-8884.1317.

- 1 2 3 Wimmer, Andreas (28 July 2015). "Is Diversity Detrimental? Ethnic Fractionalization, Public Goods Provision, and the Historical Legacies of Stateness". Comparative Political Studies: 0010414015592645. doi:10.1177/0010414015592645. ISSN 0010-4140.

- 1 2 Kymlicka, Will; Banting, Keith (1 September 2006). "Immigration, Multiculturalism, and the Welfare State". Ethics & International Affairs. 20 (03): 281–304. doi:10.1111/j.1747-7093.2006.00027.x. ISSN 1747-7093.

- ↑ Garand, James C.; Xu, Ping; Davis, Belinda C. (1 December 2015). "Immigration Attitudes and Support for the Welfare State in the American Mass Public". American Journal of Political Science: n/a–n/a. doi:10.1111/ajps.12233. ISSN 1540-5907.

- ↑ Geay, Charlotte; McNally, Sandra; Telhaj, Shqiponja (1 August 2013). "Non-native Speakers of English in the Classroom: What Are the Effects on Pupil Performance?*". The Economic Journal. 123 (570): F281–F307. doi:10.1111/ecoj.12054. ISSN 1468-0297.

- ↑ Ohinata, Asako; van Ours, Jan C. (1 August 2013). "How Immigrant Children Affect the Academic Achievement of Native Dutch Children". The Economic Journal. 123 (570): F308–F331. doi:10.1111/ecoj.12052. ISSN 1468-0297.

- ↑ Schneeweis, Nicole (1 August 2015). "Immigrant concentration in schools: Consequences for native and migrant students". Labour Economics. 35: 63–76. doi:10.1016/j.labeco.2015.03.004.

- ↑ "Gender and Racial Differences in Peer Effects of Limited English Students: A Story of Language or Ethnicity?". www.iza.org. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ↑ Bohlen, Celestine (25 January 2016). "Study Finds Children of Immigrants Embracing 'Frenchness'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- ↑ "Achieving the American Dream: Cultural Distance, Cultural Diversity and Economic Performance | Oxford Economic and Social History Working Papers | Working Papers". www.economics.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ↑ Blau, Francine D. (2015-11-01). "Immigrants and Gender Roles: Assimilation vs. Culture". National Bureau of Economic Research.

- 1 2 Röder, Antje; Mühlau, Peter (1 March 2014). "Are They Acculturating? Europe's Immigrants and Gender Egalitarianism". Social Forces. 92 (3): 899–928. doi:10.1093/sf/sot126. ISSN 0037-7732.

- 1 2 Spierings, Niels (16 April 2015). "Gender Equality Attitudes among Turks in Western Europe and Turkey: The Interrelated Impact of Migration and Parents' Attitudes". Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 41 (5): 749–771. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2014.948394. ISSN 1369-183X.

- ↑ Fleischmann, Fenella; Kristen, Cornelia; Contributions, With; Research, Including the Provision of Data and Analyses Instrumental to The; by; Heath, Anthony F.; Brinbaum, Yaël; Deboosere, Patrick; Granato, Nadia (1 July 2014). "Gender Inequalities in the Education of the Second Generation in Western Countries". Sociology of Education. 87 (3): 143–170. doi:10.1177/0038040714537836. ISSN 0038-0407.

- 1 2 Röder, Antje (1 December 2015). "Immigrants' Attitudes toward Homosexuality: Socialization, Religion, and Acculturation in European Host Societies". International Migration Review. 49 (4): 1042–1070. doi:10.1111/imre.12113. ISSN 1747-7379.

- ↑ Mesoudi, Alex; Magid, Kesson; Hussain, Delwar (13 January 2016). "How Do People Become W.E.I.R.D.? Migration Reveals the Cultural Transmission Mechanisms Underlying Variation in Psychological Processes". PLoS ONE. 11 (1): e0147162. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0147162.

- ↑ Avitabile, Ciro; Clots-Figueras, Irma; Masella, Paolo (1 August 2013). "The Effect of Birthright Citizenship on Parental Integration Outcomes". The Journal of Law and Economics. 56 (3): 777–810. doi:10.1086/673266. ISSN 0022-2186.

- ↑ Gathmann, Christina (2015-02-01). "Naturalization and citizenship: Who benefits?". IZA World of Labor. doi:10.15185/izawol.125.

- 1 2 Duncan, Brian; Trejo, Stephen J. "Tracking Intergenerational Progress for Immigrant Groups: The Problem of Ethnic Attrition". American Economic Review. 101 (3): 603–608. doi:10.1257/aer.101.3.603.

- ↑ Alba, Richard; Islam, Tariqul (1 January 2009). "The Case of the Disappearing Mexican Americans: An Ethnic-Identity Mystery". Population Research and Policy Review. 28 (2): 109–121. doi:10.1007/s11113-008-9081-x. JSTOR 20616620.

- ↑ Duncan, Brian; Trejo, Stephen. "The Complexity of Immigrant Generations: Implications for Assessing the Socioeconomic Integration of Hispanics and Asians" (PDF). doi:10.3386/w21982.

- ↑ Damm, Anna Piil; Dustmann, Christian. "Does Growing Up in a High Crime Neighborhood Affect Youth Criminal Behavior? †". American Economic Review. 104 (6): 1806–1832. doi:10.1257/aer.104.6.1806.

- ↑ Åslund, Olof; Edin, Per-Anders; Fredriksson, Peter; Grönqvist, Hans. "Peers, Neighborhoods, and Immigrant Student Achievement: Evidence from a Placement Policy". American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 3 (2): 67–95. doi:10.1257/app.3.2.67.

- ↑ Damm, Anna Piil (1 January 2014). "Neighborhood quality and labor market outcomes: Evidence from quasi-random neighborhood assignment of immigrants". Journal of Urban Economics. Spatial Dimensions of Labor Markets. 79: 139–166. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2013.08.004.

- ↑ Damm, Anna Piil (1 April 2009). "Ethnic Enclaves and Immigrant Labor Market Outcomes: Quasi‐Experimental Evidence". Journal of Labor Economics. 27 (2): 281–314. doi:10.1086/599336. ISSN 0734-306X.

- ↑ Edin, Per-Anders; Fredriksson, Peter; Åslund, Olof (1 February 2003). "Ethnic Enclaves and the Economic Success of Immigrants—Evidence from a Natural Experiment". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 118 (1): 329–357. doi:10.1162/00335530360535225. ISSN 0033-5533.

- ↑ "IZA - Institute for the Study of Labor". www.iza.org. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ Algan, Yann; Hémet, Camille; Laitin, David D. (4 May 2016). "The Social Effects of Ethnic Diversity at the Local Level: A Natural Experiment with Exogenous Residential Allocation". Journal of Political Economy: 000–000. doi:10.1086/686010. ISSN 0022-3808.

- ↑ Levy, Morris (1 December 2015). "The Effect of Immigration from Mexico on Social Capital in the United States". International Migration Review: n/a–n/a. doi:10.1111/imre.12231. ISSN 1747-7379.

- 1 2 "IZA World of Labor - Do immigrants improve the health of native workers?". wol.iza.org. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ↑ Buonanno, Paolo; Drago, Francesco; Galbiati, Roberto; Zanella, Giulio (1 July 2011). "Crime in Europe and the United States: dissecting the 'reversal of misfortunes'". Economic Policy. 26 (67): 347–385. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0327.2011.00267.x. ISSN 0266-4658.

- 1 2 3 Bell, Brian; Oxford, University of; UK. "Crime and immigration". IZA World of Labor. doi:10.15185/izawol.33.

- 1 2 3 Papadopoulos, Georgios (2 July 2014). "Immigration status and property crime: an application of estimators for underreported outcomes". IZA Journal of Migration. 3 (1): 12. doi:10.1186/2193-9039-3-12. ISSN 2193-9039.

- ↑ Bianchi, Milo; Buonanno, Paolo; Pinotti, Paolo (1 December 2012). "Do Immigrants Cause Crime?". Journal of the European Economic Association. 10 (6): 1318–1347. doi:10.1111/j.1542-4774.2012.01085.x. ISSN 1542-4774.

- ↑ Nunziata, Luca (4 March 2015). "Immigration and crime: evidence from victimization data". Journal of Population Economics. 28 (3): 697–736. doi:10.1007/s00148-015-0543-2. ISSN 0933-1433.

- ↑ Jaitman, Laura; Machin, Stephen (25 October 2013). "Crime and immigration: new evidence from England and Wales". IZA Journal of Migration. 2 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1186/2193-9039-2-19. ISSN 2193-9039.

- ↑ Bell, Brian; Fasani, Francesco; Machin, Stephen (10 October 2012). "Crime and Immigration: Evidence from Large Immigrant Waves". Review of Economics and Statistics. 95 (4): 1278–1290. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00337. ISSN 0034-6535.

- ↑ Bell, Brian; Machin, Stephen (1 February 2013). "Immigrant Enclaves and Crime*". Journal of Regional Science. 53 (1): 118–141. doi:10.1111/jors.12003. ISSN 1467-9787.

- ↑ Wadsworth, Tim (1 June 2010). "Is Immigration Responsible for the Crime Drop? An Assessment of the Influence of Immigration on Changes in Violent Crime Between 1990 and 2000*". Social Science Quarterly. 91 (2): 531–553. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6237.2010.00706.x. ISSN 1540-6237.

- ↑ Piopiunik, Marc; Ruhose, Jens (6 April 2015). "Immigration, Regional Conditions, and Crime: Evidence from an Allocation Policy in Germany". Rochester, NY.

- ↑ "Understanding the Role of Immigrants' Legal Status: Evidence from Policy Experiments". www.iza.org. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- ↑ Mastrobuoni, Giovanni; Pinotti, Paolo. "Legal Status and the Criminal Activity of Immigrants †". American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 7 (2): 175–206. doi:10.1257/app.20140039.

- ↑ Baker, Scott R. "Effects of Immigrant Legalization on Crime †". American Economic Review. 105 (5): 210–213. doi:10.1257/aer.p20151041.

- ↑ Pinotti, Paolo (1 October 2014). "Clicking on Heaven's Door: The Effect of Immigrant Legalization on Crime". Rochester, NY.

- ↑ Fasani, Francesco (1 January 2014). "Understanding the Role of Immigrants' Legal Status: Evidence from Policy Experiments". Centre for Research and Analysis of Migration (CReAM), Department of Economics, University College London.

- ↑ Freedman, Matthew. "Immigration, Opportunities, and Criminal Behavior". works.bepress.com. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- 1 2 "Diskriminering i rättsprocessen - Brå". www.bra.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ↑ Hällsten, Martin; Szulkin, Ryszard; Sarnecki, Jerzy (1 May 2013). "Crime as a Price of Inequality? The Gap in Registered Crime between Childhood Immigrants, Children of Immigrants and Children of Native Swedes". British Journal of Criminology. 53 (3): 456–481. doi:10.1093/bjc/azt005. ISSN 0007-0955.

- 1 2 Crocitti, Stefania. Immigration, Crime, and Criminalization in Italy - Oxford Handbooks. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199859016.013.029.

- 1 2 Colombo, Asher (1 November 2013). "Foreigners and immigrants in Italy's penal and administrative detention systems". European Journal of Criminology. 10 (6): 746–759. doi:10.1177/1477370813495128. ISSN 1477-3708.

- ↑ Parmar, Alpa. Ethnicities, Racism, and Crime in England and Wales - Oxford Handbooks. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199859016.013.014.

- ↑ Holmberg, Lars; Kyvsgaard, Britta. "Are Immigrants and Their Descendants Discriminated against in the Danish Criminal Justice System?". Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention. 4 (2): 125–142. doi:10.1080/14043850310020027.

- ↑ Roché, Sebastian; Gordon, Mirta B.; Depuiset, Marie-Aude. Case Study - Oxford Handbooks. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199859016.013.030.

- ↑ Light, Michael T. (1 March 2016). "The Punishment Consequences of Lacking National Membership in Germany, 1998–2010". Social Forces. 94 (3): 1385–1408. doi:10.1093/sf/sov084. ISSN 0037-7732.

- ↑ Wermink, Hilde; Johnson, Brian D.; Nieuwbeerta, Paul; Keijser, Jan W. de (1 November 2015). "Expanding the scope of sentencing research: Determinants of juvenile and adult punishment in the Netherlands". European Journal of Criminology. 12 (6): 739–768. doi:10.1177/1477370815597253. ISSN 1477-3708.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "IZA - Institute for the Study of Labor". www.iza.org. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- 1 2 3 Zschirnt, Eva; Ruedin, Didier (27 May 2016). "Ethnic discrimination in hiring decisions: a meta-analysis of correspondence tests 1990–2015". Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 42 (7): 1115–1134. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2015.1133279. ISSN 1369-183X.

- 1 2 Riach, P. A.; Rich, J. (1 November 2002). "Field Experiments of Discrimination in the Market Place*". The Economic Journal. 112 (483): F480–F518. doi:10.1111/1468-0297.00080. ISSN 1468-0297.

- ↑ Ayres, Ian; Siegelman, Peter (1 January 1995). "Race and Gender Discrimination in Bargaining for a New Car". American Economic Review. 85 (3): 304–21.

- ↑ Doleac, Jennifer L.; Stein, Luke C.D. (1 November 2013). "The Visible Hand: Race and Online Market Outcomes". The Economic Journal. 123 (572): F469–F492. doi:10.1111/ecoj.12082. ISSN 1468-0297.

- ↑ Warren, Patricia Y.; Tomaskovic-Devey, Donald (1 May 2009). "Racial profiling and searches: Did the politics of racial profiling change police behavior?*". Criminology & Public Policy. 8 (2): 343–369. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9133.2009.00556.x. ISSN 1745-9133.

- ↑ Statistics on Race and the Criminal Justice System 2008/09, p. 8., 22

- 1 2 West, Jeremy (November 2015). "Racial Bias in Police Investigations" (PDF). MIT.edu (Working paper). Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- ↑ Donohue III, John J.; Levitt, Steven D. (1 January 2001). "The Impact of Race on Policing and Arrests". The Journal of Law & Economics. 44 (2): 367–394. doi:10.1086/322810. JSTOR 10.1086/322810.

- ↑ Abrams, David S.; Bertrand, Marianne; Mullainathan, Sendhil (1 June 2012). "Do Judges Vary in Their Treatment of Race?". The Journal of Legal Studies. 41 (2): 347–383. doi:10.1086/666006. ISSN 0047-2530.

- ↑ Mustard, David B. (1 April 2001). "Racial, Ethnic, and Gender Disparities in Sentencing: Evidence from the U.S. Federal Courts". The Journal of Law and Economics. 44 (1): 285–314. doi:10.1086/320276. ISSN 0022-2186.

- 1 2 Anwar, Shamena; Bayer, Patrick; Hjalmarsson, Randi (1 May 2012). "The Impact of Jury Race in Criminal Trials". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 127 (2): 1017–1055. doi:10.1093/qje/qjs014. ISSN 0033-5533.

- ↑ Daudistel, Howard C.; Hosch, Harmon M.; Holmes, Malcolm D.; Graves, Joseph B. (1 February 1999). "Effects of Defendant Ethnicity on Juries' Dispositions of Felony Cases1". Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 29 (2): 317–336. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1999.tb01389.x. ISSN 1559-1816.

- 1 2 Depew, Briggs; Eren, Ozkan; Mocan, Naci (1 February 2016). "Judges, Juveniles and In-group Bias". National Bureau of Economic Research.

- ↑ Milkman, Katherine L.; Akinola, Modupe; Chugh, Dolly (1 November 2015). "What happens before? A field experiment exploring how pay and representation differentially shape bias on the pathway into organizations". The Journal of Applied Psychology. 100 (6): 1678–1712. doi:10.1037/apl0000022. ISSN 1939-1854. PMID 25867167.

- ↑ "Espenshade, T.J. and Radford, A.W.: No Longer Separate, Not Yet Equal: Race and Class in Elite College Admission and Campus Life. (eBook, Paperback and Hardcover)". press.princeton.edu. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ↑ Ondrich, Jan; Ross, Stephen; Yinger, John (1 November 2003). "Now You See It, Now You Don't: Why Do Real Estate Agents Withhold Available Houses from Black Customers?". Review of Economics and Statistics. 85 (4): 854–873. doi:10.1162/003465303772815772. ISSN 0034-6535.