Idiom

An idiom (Latin: idioma, "special property", from Greek: ἰδίωμα – idíōma, "special feature, special phrasing, a peculiarity", f. Greek: ἴδιος – ídios, "one’s own") is a phrase or a fixed expression that has a figurative, or sometimes literal, meaning. Categorized as formulaic language, an idiom's figurative meaning is different from the literal meaning.[1] There are thousands of idioms, occurring frequently in all languages. It is estimated that there are at least twenty-five thousand idiomatic expressions in the English language.[2]

Examples

The following sentences contain idioms. The fixed words constituting the idiom in each case are bolded:[3]

- Ball is in your court. This means it is up to you to make the next decision or step.

- Back to the drawing board. This means when an attempt fails and you have to start all over.

- She is pulling my leg. This means to tease them by telling them something untrue.

- I'll drop you a line. This means to send a message or start a telecommunicated conversation.

- Be glad to see the back of. This means to be happy when a person leaves.

- You should keep an eye out for that. This means to maintain awareness of it as it occurs.

- You need to pull up your socks. This means you need to make an effort to improve your work or behaviour because it is not good enough.

- You are out to lunch. This means you are wrong in what your belief is.

- I can't keep my head above water. This means to manage a situation.

- It's raining cats and dogs. This means to rain very heavily.

- Oh no! You spilled the beans! You let the cat out the bag. This means to let out a secret.

- Why are you feeling blue? This means to feel sad.

- That costs an arm and a leg. This means a large amount of money.

- It is not rocket science. This means something is not exceedingly difficult.

- Put a cork in it. This means, "shut up!" (another idiom), be quiet, and stop talking.

- I'm screwed. This means that one is doomed, is in big trouble, or has made a huge mistake.

- I'll bet. This is a hyperbolic or sarcastic way of saying "certainly" or "of course".

- This is a piece of cake! This means a task will be easy.

- Keep your eye on it. This means to watch or monitor something or a person/persons closely and carefully.

- Wear Your Heart On Your Sleeve. This means to be open, maybe too open, about your feelings in the public.

Each of the word combinations in bold has at least two meanings: a literal meaning and a figurative meaning. Such expressions that are typical for a language can appear as words, combinations of words, phrases, entire clauses, and entire sentences.

- The devil is in the details.

- The early bird gets the worm.

- Break a leg.

- Waste not, want not.

- Go take a chill pill.

- I have butterflies in my stomach.

Expressions such as these have figurative meaning. When one says "The devil is in the details", one is not expressing a belief in demons, but rather one means that things may look good on the surface, but upon scrutiny, undesirable aspects are revealed. Similarly, when one says "The early bird gets the worm", one is not suggesting that there is only one opportunity; rather one means there are plenty of opportunities, but for the sake of the idiom one plays along, and imagines that there is only one. Alternatively, the figurative translation of this phrase is that the most attentive and astute individual, or perhaps the hardest working or most opportunistic receives the most desirable opportunity. On the other hand, "Waste not, want not" is completely devoid of a figurative meaning. It counts as an idiom, however, because it has a literal meaning and people keep saying it.

Derivations

Many idiomatic expressions, in their original use, were not figurative but had literal meaning.

For instance: spill the beans, meaning to reveal a secret, originates from an ancient method of democratic voting, wherein a voter would put a bean into one of several cups to indicate which candidate he wanted to cast his vote for. If the jars were spilled before the counting of votes was complete, anyone would be able to see which jar had more beans, and therefore which candidate was the winner. Over time, the practice was discontinued and the idiom became figurative.

break a leg: meaning good luck in a performance or presentation. It is unclear how this common idiom originated, but many have it coming from belief in superstitions in one way or another. A particularly simple one says that it comes from the belief that one ought not to utter the words "good luck" to an actor. By wishing someone bad luck, it is cynically supposed that the opposite will occur.[4]

Compositionality

In linguistics, idioms are usually presumed to be figures of speech contradicting the principle of compositionality. That compositionality is the key notion for the analysis of idioms is emphasized in most accounts of idioms.[5][6] This principle states that the meaning of a whole should be constructed from the meanings of the parts that make up the whole. In other words, one should be in a position to understand the whole if one understands the meanings of each of the parts that make up the whole. The following example is widely employed to illustrate the point:

Fred kicked the bucket.

Understood compositionally, Fred has literally kicked an actual, physical bucket. The much more likely idiomatic reading, however, is non-compositional: Fred is understood to have died. Arriving at the idiomatic reading from the literal reading is unlikely for most speakers. What this means is that the idiomatic reading is, rather, stored as a single lexical item that is now largely independent of the literal reading.

In phraseology, idioms are defined as a sub-type of phraseme, the meaning of which is not the regular sum of the meanings of its component parts.[7] John Saeed defines an idiom as collocated words that became affixed to each other until metamorphosing into a fossilised term.[8] This collocation of words redefines each component word in the word-group and becomes an idiomatic expression. Idioms usually do not translate well; in some cases, when an idiom is translated directly word-for-word into another language, either its meaning is changed or it is meaningless.

When two or three words are often used together in a particular sequence, the words are said to be irreversible binomials, or Siamese twins. Usage will prevent the words from being displaced or rearranged. For example, a person may be left "high and dry" but never "dry and high". This idiom in turn means that the person is left in their former condition rather than being assisted so that their condition improves. Not all Siamese twins are idioms, however. "Chips and dip" is an irreversible binomial, but it refers to literal food items, not idiomatic ones.

Translating idioms

A literal translation (word-by-word) of opaque idioms will most likely not convey the same meaning in other languages. The following list shows idioms from other languages that are analogous to kick the bucket in the English language.

- Kurdish: Daya takhtakayaa ' to hit the wood. a wooden table dead people are washed on.

- Arabic: Wad'aa" he said goodbye

- Afrikaans: lepel deur die dak steek 'to push a spoon through the ceiling (roof)',

- Bulgarian: да ритнеш камбаната 'to kick the bell'

- Czech: natáhnout bačkory 'stretch the slippers'

- Danish: at stille træskoene 'to take off the clogs',

- Dutch: het loodje leggen 'to lay the piece of lead' or de pijp aan Maarten geven 'to give the pipe to Maarten' or zijn laatste pijp roken 'to smoke one's last pipe' or de pijp uit gaan 'to leave to (rabbit) hole'/'leave the (duck) decoy',

- Farsi: daare faani raa vedaa' goft 'said goodbye to the mortal dwelling',

- Finnish: potkaista tyhjää 'to kick the void' or heittää veivinsä 'to toss away the crank' or kasvaa koiranputkea 'to be growing cow parsley' or heittää lusikan nurkkaan 'to toss the spoon to the corner' or oikaista koipensa 'to stretch the shanks'

- French: manger des pissenlits par la racine 'to eat dandelions by the root' or casser sa pipe 'to break his pipe' or passer l'arme à gauche 'pass the weapon to the left',

- German: den Löffel abgeben, 'to hand the spoon back'; ins Gras beißen, 'to bite (into) the grass'; or sich die Radieschen von unten ansehen, 'look at the radishes from underneath'.

- Hindi: Patta kat jana 'to cue the leaf'

- Hungarian: Feldobja a lábát 'to throw his foot up' or Fűbe harap 'to bite into the grass' or Alulról szagolja az ibolyát 'to smell the violets from underneath' or Elpatkolt 'to fail shoeing (a horse)',

- Greek: τινάζω τα πέταλα 'to shake the horse-shoes',

- Icelandic: Að geispa golunni 'to yawn the breeze',

- Italian: tirare le cuoia 'to pull the skins',

- Latvian: nolikt karoti 'to put the spoon down'[9]

- Lithuanian: pakratyti kojas 'to shake the legs',

- Neapolitan: s'ha fatt 'a cartell 'to make the folder',

- Norwegian: å parkere tøflene 'to park the slippers', sjekke ut 'check out', legge inn årene 'pull in the oars', takke for seg 'thank for yourself', sløkke og låse 'turn off and lock', vandre 'wander', ta kvelden 'call it a night',

- Polish: kopnąć w kalendarz 'to kick the calendar', wyciągnąć kopyta 'to stretch the hooves', wąchać kwiatki od spodu 'to smell the flowers from underneath', 'wsiąść w czarny autobus' 'to get on a black bus', 'pójść na tamten świat' 'go to the other world', 'walnąć w ramy' 'to hit the frame',

- Portuguese: bater as botas 'to beat the boots', esticar o pernil 'to stretch the leg', or fazer tijolo 'to make a brick', plus comer capim pela raiz 'to eat grass by the root', abotoar o paletó 'to button up the blazer/coat', esticar as canelas 'to stretch the shanks',

- Romanian: a da colțul 'to turn the corner', or i-a sunat ceasul 'his clock has rung', or a da ortul popii 'to give the coin to the priest', or a-și da duhul 'to give one's spirit'

- Russian: сыграть в ящик (sygrat' v yaschik) 'to play into the box', дать дуба 'to give the oak', откинуть копыта 'to throw back the hoofs'

- Slovenian: šel je rakom žvižgat 'he went to whistle to the crabs',

- Spanish: estirar la pata 'to stretch the leg' or palmarla 'to pop off'

- Swedish: trilla av pinnen 'to roll off the stick' very similar to 'walk the plank'.(as in a parrot or other bird suddenly dying and falling off its perch), ta ner skylten 'take the sign down' or sätta skorna 'take the shoes off'

- Tlingit: dákde kákw aawayaa 'to take one’s basket into the woods',

- Turkish: Nalları dikti' 'put the horseshoes in the air', as in a horse dropped dead to the ground,

- Ukrainian: врізати дуба 'to cut the oak (as in building a coffin)',

- Urdu: Haathi nikal gaya dum phans gayi ہاتھی نکل گیا دم پھنس گئی 'The elephant escaped but his tail got stuck'

Some idioms are transparent.[10] Much of their meaning does get through if they are taken (or translated) literally. For example, lay one's cards on the table meaning to reveal previously unknown intentions, or to reveal a secret. Transparency is a matter of degree; spill the beans (to let secret information become known) and leave no stone unturned (to do everything possible in order to achieve or find something) are not entirely literally interpretable, but only involve a slight metaphorical broadening. Another category of idioms is a word having several meanings, sometimes simultaneously, sometimes discerned from the context of its usage. This is seen in the (mostly uninflected) English language in polysemes, the common use of the same word for an activity, for those engaged in it, for the product used, for the place or time of an activity, and sometimes for a verb.

Idioms tend to confuse those unfamiliar with them; students of a new language must learn its idiomatic expressions as vocabulary. Many natural language words have idiomatic origins, but are assimilated, so losing their figurative senses, for example, in Portuguese, the expression saber de coração 'to know by heart', with the same meaning as in English, was shortened to 'saber de cor', and, later, to the verb decorar, meaning memorize.

In 2015, TED collected 40 examples of bizarre idioms that cannot be translated literally. They include the Swedish saying "to slide in on a shrimp sandwich", which refers to somebody who didn't have to work to get where they are."[11]

Dealing with non-compositionality

The non-compositionality of meaning of idioms challenges theories of syntax. The fixed words of many idioms do not qualify as constituents in any sense. For example:

How do we get to the bottom of this situation?

The fixed words of this idiom (in bold) do not form a constituent in any theory's analysis of syntactic structure because the object of the preposition (here this situation) is not part of the idiom (but rather it is an argument of the idiom). One can know that it is not part of the idiom because it is variable; for example, How do we get to the bottom of this situation / the claim / the phenomenon / her statement / etc. What this means is that theories of syntax that take the constituent to be the fundamental unit of syntactic analysis are challenged. The manner in which units of meaning are assigned to units of syntax remains unclear. This problem has motivated a tremendous amount of discussion and debate in linguistics circles and it is a primary motivator behind the Construction Grammar framework.[12]

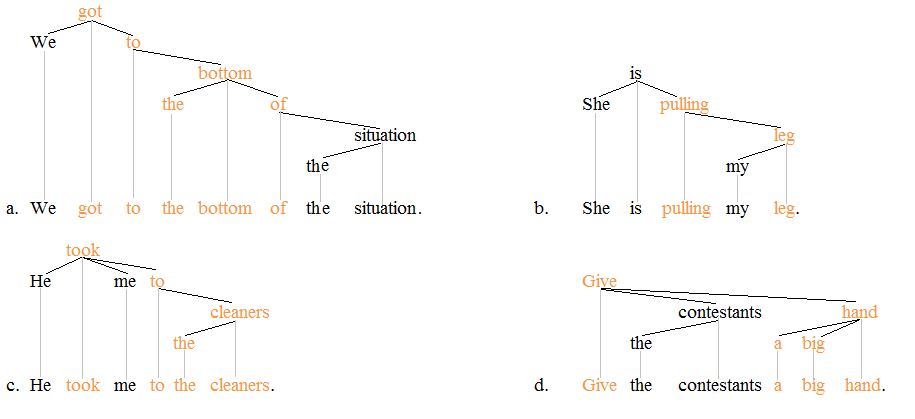

A relatively recent development in the syntactic analysis of idioms departs from a constituent-based account of syntactic structure, preferring instead the catena-based account. The catena unit was introduced to linguistics by William O'Grady in 1998. Any word or any combination of words that are linked together by dependencies qualifies as a catena.[13] The words constituting idioms are stored as catenae in the lexicon, and as such, they are concrete units of syntax. The dependency grammar trees of a few sentences containing non-constituent idioms illustrate the point:

The fixed words of the idiom (in orange) in each case are linked together by dependencies; they form a catena. The material that is outside of the idiom (in normal black script) is not part of the idiom. The following two trees illustrate proverbs:

The fixed words of the proverbs (in orange) again form a catena each time. The adjective nitty-gritty and the adverb always are not part of the respective proverb and their appearance does not interrupt the fixed words of the proverb. A caveat concerning the catena-based analysis of idioms concerns their status in the lexicon. Idioms are lexical items, which means they are stored as catenae in the lexicon. In the actual syntax, however, some idioms can be broken up by various functional constructions.

The catena-based analysis of idioms provides a basis for an understanding of meaning compositionality. The Principle of Compositionality can in fact be maintained. Units of meaning are being assigned to catenae, whereby many of these catenae are not constituents.

See also

References

- ↑ The Oxford companion to the English language (1992:495f.)

- ↑ Jackendoff (1997).

- ↑ Crystal (1997:189), Radford (2004:187f.), Jurafsky and Martin (2000:597f.).

- ↑ Phrase Finder is copyright Gary Martin, 1996-2015. All rights reserved. "Break a leg". phrases.org.uk.

- ↑ Radford (2004:187f.)

- ↑ Portner (2005:33f).

- ↑ Mel’čuk (1995:167-232).

- ↑ For Saeed's definition, see Saeed (2003:60).

- ↑ The Oxford Companion to the English Language (1992): 495f.

- ↑ Gibbs, R. W. (1987)

- ↑ "40 brilliant idioms that simply can't be translated literally". TED Blog. Retrieved 2016-04-08.

- ↑ Culicver and Jackendoff (2005:32ff.)

- ↑ Osborne and Groß (2012:173ff.)

Bibliography

- Crystal, A dictionary of linguistics and phonetics, 4th edition. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers.

- Culicover, P. and R. Jackendoff. 2005. Simpler syntax. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Gibbs, R. 1987. Linguistic factors in children's understanding of idioms. Journal of Child Language, 14, 569–586.

- Jackendoff, R. 1997. The architecture of the language faculty. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Jurafsky, D. and J. Martin. 2008. Speech and language processing: An introduction to natural language processing, computational linguistics, and speech recognition. Dorling Kindersley (India): Pearson Education, Inc.

- Leaney, C. 2005. In the know: Understanding and using idioms. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Mel’čuk, I. 1995. Phrasemes in language and phraseology in linguistics. In M. Everaert, E.-J. van der Linden, A. Schenk and R. Schreuder (eds.), Idioms: Structural and psychological perspectives, 167–232. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- O’Grady, W. 1998. The syntax of idioms. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 16, 79-312.

- Osborne, T. and T. Groß 2012. Constructions are catenae: Construction Grammar meets Dependency Grammar. Cognitive Linguistics 23, 1, 163-214.

- Portner, P. 2005. What is meaning?: Fundamentals of formal semantics. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Radford, A. English syntax: An introduction. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Saeed, J. 2003. Semantics. 2nd edition. Oxford: Blackwell.

External links

| Look up idiom, Category:Idioms by language, or Category:English idioms in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Idioms.in - Online English idioms dictionary.

- babelite.org - Online cross-language idioms dictionary EN, ES, FR, PT.