Hurricane Sandy

| Category 3 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

Hurricane Sandy as a major hurricane near Jamaica and Cuba on October 25, 2012 | |

| Formed | October 22, 2012 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | November 2, 2012[1] |

| (Extratropical after October 29) | |

| Highest winds |

1-minute sustained: 115 mph (185 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 940 mbar (hPa); 27.76 inHg |

| Fatalities | 233 total (direct and indirect)[2] |

| Damage |

$75 billion (2012 USD) (Second-costliest hurricane in U.S. history[1]) |

| Areas affected | Greater Antilles, Bahamas, most of the eastern United States (especially the coastal Mid-Atlantic States), Bermuda, eastern Canada |

| Part of the 2012 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|

Impact Other wikis | |

Hurricane Sandy (unofficially referred to as "Superstorm Sandy") was the deadliest and most destructive hurricane of the 2012 Atlantic hurricane season, and the second-costliest hurricane in United States history. Classified as the eighteenth named storm, tenth hurricane and second major hurricane of the year, Sandy was a Category 3 storm at its peak intensity when it made landfall in Cuba.[1] While it was a Category 2 storm off the coast of the Northeastern United States, the storm became the largest Atlantic hurricane on record (as measured by diameter, with winds spanning 1,100 miles (1,800 km)).[3][4] Estimates as of 2015 assessed damage to have been about $75 billion (2012 USD), a total surpassed only by Hurricane Katrina.[5] At least 233 people were killed along the path of the storm in eight countries.[2][6]

Sandy developed from a tropical wave in the western Caribbean Sea on October 22, quickly strengthened, and was upgraded to Tropical Storm Sandy six hours later. Sandy moved slowly northward toward the Greater Antilles and gradually intensified. On October 24, Sandy became a hurricane, made landfall near Kingston, Jamaica, re-emerged a few hours later into the Caribbean Sea and strengthened into a Category 2 hurricane. On October 25, Sandy hit Cuba as a Category 3 hurricane, then weakened to a Category 1 hurricane. Early on October 26, Sandy moved through the Bahamas.[7] On October 27, Sandy briefly weakened to a tropical storm and then restrengthened to a Category 1 hurricane. Early on October 29, Sandy curved west-northwest (the "left turn" or "left hook") and then[8] moved ashore near Brigantine, New Jersey, just to the northeast of Atlantic City, as a post-tropical cyclone with hurricane-force winds.[1][9]

In Jamaica, winds left 70% of residents without electricity, blew roofs off buildings, killed one, and caused about $100 million (2012 USD) in damage. Sandy's outer bands brought flooding to Haiti, killing at least 54, causing food shortages, and leaving about 200,000 homeless; the hurricane also caused two deaths in the Dominican Republic. In Puerto Rico, one man was swept away by a swollen river. In Cuba, there was extensive coastal flooding and wind damage inland, destroying some 15,000 homes, killing 11, and causing $2 billion (2012 USD) in damage. Sandy caused two deaths and damage estimated at $700 million (2012 USD) in The Bahamas. In Canada, two were killed in Ontario and an estimated $100 million (2012 CAD) in damage was caused throughout Ontario and Quebec.[10]

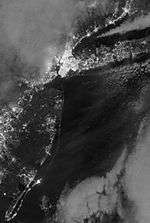

In the United States, Hurricane Sandy affected 24 states, including the entire eastern seaboard from Florida to Maine and west across the Appalachian Mountains to Michigan and Wisconsin, with particularly severe damage in New Jersey and New York. Its storm surge hit New York City on October 29, flooding streets, tunnels and subway lines and cutting power in and around the city.[11][12] Damage in the United States amounted to $71.4 billion (2013 USD).[13]

Meteorological history

Hurricane Sandy began as a low pressure system which developed sufficient organized convection to be classified as Tropical Depression Eighteen on October 22 south of Kingston, Jamaica.[14] It moved slowly at first due to a ridge to the north. Low wind shear and warm waters allowed for strengthening,[14] and the system was named Tropical Storm Sandy late on October 22.[15] Early on October 24, an eye began developing, and it was moving steadily northward due to an approaching trough.[16] Later that day, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) upgraded Sandy to hurricane status about 65 mi (105 km) south of Kingston, Jamaica.[17] At about 1900 UTC that day, Sandy made landfall near Kingston with winds of about 85 mph (140 km/h).[18] Just offshore Cuba, Sandy rapidly intensified to winds of 115 mph (185 km/h),[1] and at that intensity it made landfall just west of Santiago de Cuba at 0525 UTC on October 25.[19]

After Sandy exited Cuba, the structure became disorganized,[20] and it turned to the north-northwest over the Bahamas.[21] By October 27, Sandy was no longer fully tropical, and despite strong shear, it maintained convection due to influence from an approaching trough; the same trough turned the hurricane to the northeast.[22] After briefly weakening to a tropical storm,[23] Sandy re-intensified into a hurricane,[24] and on October 28 an eye began redeveloping.[25] The storm moved around an upper-level low over the eastern United States and also to the southwest of a ridge over Atlantic Canada, turning it to the northwest.[26] Sandy briefly re-intensified to Category 2 intensity on the morning of October 29, around which time it had a wind diameter of over 1,150 miles (1,850 km).[27] The convection diminished while the hurricane accelerated toward the New Jersey coast,[28] and the hurricane was no longer tropical by 2100 UTC on October 29.[29] About 2 1/2 hours later, Sandy made landfall near Brigantine, New Jersey,[30] with winds of 80 mph (130 km/h).[1] During the next two days, Sandy's remnants drifted northward and then northeastward over Ontario, before merging with another low pressure area over Eastern Canada.[1]

Forecasts

On October 23, 2012, the path of Hurricane Sandy was correctly predicted by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) headquartered in Reading, England nearly eight days in advance of its striking the American East Coast. The computer model noted that the storm would turn west towards land and strike the New York/New Jersey region on October 29, rather than turn east and head out to the open Atlantic as most hurricanes in this position do. By October 27, four days after the ECMWF made its prediction, the National Weather Service and National Hurricane Center confirmed the path of the hurricane predicted by the European model. The National Weather Service was criticized for not employing its higher-resolution forecast models the way that its European counterpart did. A hardware and software upgrade completed at the end of 2013 enabled the weather service to make more accurate predictions, and do so far more in advance than the technology in 2012 had allowed.[31]

Relation to global warming

According to NCAR senior climatologist Kevin E. Trenberth, "The answer to the oft-asked question of whether an event is caused by climate change is that it is the wrong question. All weather events are affected by climate change because the environment in which they occur is warmer and moister than it used to be."[32] Although NOAA meteorologist Martin Hoerling attributes Sandy to "little more than the coincidental alignment of a tropical storm with an extratropical storm",[33] Trenberth does agree that the storm was caused by "natural variability" but adds that it was "enhanced by global warming".[34] One factor contributing to the storm's strength was abnormally warm sea surface temperatures offshore the East Coast of the United States—more than 3 °C (5 °F) above normal, to which global warming had contributed 0.6 °C (1 °F).[34] As the temperature of the atmosphere increases, the capacity to hold water increases, leading to stronger storms and higher rainfall amounts.[34]

As they move north, Atlantic hurricanes typically are forced east and out to sea by the Prevailing Westerlies.[35] In Sandy's case, this typical pattern was blocked by a ridge of high pressure over Greenland resulting in a negative North Atlantic Oscillation, forming a kink in the jet stream, causing it to double back on itself off the East Coast. Sandy was caught up in this northwesterly flow.[35] The blocking pattern over Greenland also stalled an Arctic front which combined with the cyclone.[35] Mark Fischetti of Scientific American said that the jet stream's unusual shape was caused by the melting of Arctic ice.[36] Trenberth said that while a negative North Atlantic Oscillation and a blocking anticyclone were in place, the null hypothesis remained that this was just the natural variability of weather.[33] Sea level at New York and along the New Jersey coast has increased by nearly a foot over the last hundred years,[37] which contributed to the storm surge.[38] Harvard geologist Daniel P. Schrag calls Hurricane Sandy's 13-foot storm surge an example of what will, by mid-century, be the "new norm on the Eastern seaboard".[39]

Preparations

Caribbean and Bermuda

After the storm became a tropical cyclone on October 22, the Government of Jamaica issued a tropical storm watch for the entire island.[40] Early on October 23, the watch was replaced with a tropical storm warning and a hurricane watch was issued.[41] At 1500 UTC, the hurricane watch was upgraded to a hurricane warning, while the tropical storm warning was discontinued.[42] In preparation of the storm, many residents stocked up on supplies and reinforced roofing material. Acting Prime Minister Peter Phillips urged people to take this storm seriously, and also to take care of their neighbors, especially the elderly, children, and disabled. Government officials shut down schools, government buildings, and the airport in Kingston on the day prior to the arrival of Sandy. Meanwhile, numerous and early curfews were put in place to protect residents, properties, and to prevent crime.[43] Shortly after Jamaica issued its first watch on October 22, the Government of Haiti issued a tropical storm watch for Haiti.[44] By late October 23, it was modified to a tropical storm warning.[45]

The Government of Cuba posted a hurricane watch for the Cuban Provinces of Camagüey, Granma, Guantánamo, Holguín, Las Tunas, and Santiago de Cuba at 1500 UTC on October 23.[42] Only three hours later, the hurricane watch was switched to a hurricane warning.[46] The Government of the Bahamas, at 1500 UTC on October 23, issued a tropical storm watch for several Bahamian islands, including the Acklins, Cat Island, Crooked Island, Exuma, Inagua, Long Cay, Long Island, Mayaguana, Ragged Island, Rum Cay, and San Salvador Island.[42] Later that day, another tropical storm watch was issued for Abaco Islands, Andros Island, the Berry Islands, Bimini, Eleuthera, Grand Bahama, and New Providence.[46] By early on October 24, the tropical storm watch for Cat Island, Exuma, Long Island, Rum Cay, and San Salvador was upgraded to a tropical storm warning.[47]

At 1515 UTC on October 26, the Bermuda Weather Service issued a tropical storm watch for Bermuda, reflecting the enormous size of the storm and the anticipated wide-reaching impacts.[48]

United States

| Wikinews has related news: U.S. prepares for arrival of Hurricane Sandy |

Much of the East Coast of the United States, in Mid-Atlantic and New England regions, had a good chance of receiving gale-force winds, flooding, heavy rain and possibly snow early in the week of October 28 from an unusual hybrid of Hurricane Sandy and a winter storm producing a Fujiwhara effect.[49] Government weather forecasters said there was a 90% chance that the East Coast would be impacted by the storm. Jim Cisco of the Hydrometeorological Prediction Center coined the term "Frankenstorm", as Sandy was expected to merge with a storm front a few days before Halloween.[50][51][52] As coverage continued, several media outlets began eschewing this term in favor of "superstorm".[53][54] Utilities and governments along the East Coast attempted to head off long-term power failures Sandy might cause. Power companies from the Southeast to New England alerted independent contractors to be ready to help repair storm damaged equipment quickly and asked employees to cancel vacations and work longer hours. Researchers from Johns Hopkins University, using a computer model built on power outage data from previous hurricanes, conservatively forecast that 10 million customers along the Eastern Seaboard would lose power from the storm.[55]

Through regional offices in Atlanta, Philadelphia, New York City, and Boston, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) monitored Sandy, closely coordinating with state and tribal emergency management partners in Florida and the Southeast, Mid-Atlantic, and New England states.[56] President Obama signed emergency declarations on October 28 for several states expected to be impacted by Sandy, allowing them to request federal aid and make additional preparations in advance of the storm.[57] Flight cancellations and travel alerts on the U.S. East Coast were put in place in the Mid-Atlantic and the New England areas.[58] Over 5,000 commercial airline flights scheduled for October 28 and October 29 were canceled by the afternoon of October 28[59] and Amtrak canceled some services through October 29 in preparation for the storm.[60] In addition, the National Guard and U.S. Air Force put as many as 45,000 personnel in at least seven states on alert for possible duty in response to the preparations and aftermath of Sandy.[61]

Southeast

Florida

Schools on the Treasure Coast announced closures for October 26 in anticipation of Sandy.[62] A Russian intelligence-gathering ship was allowed to stay in Jacksonville to avoid Sandy; the port is not far from Kings Bay Naval Submarine Base.[63]

Carolinas

At 0900 UTC on October 26, a tropical storm watch was issued from the mouth of the Savannah River in South Carolina to Oregon Inlet, North Carolina, including Pamlico Sound.[64] Twelve hours later, the portion of the tropical storm watch from the Santee River in South Carolina to Duck, North Carolina, including Pamlico Sound, was upgraded to a warning.[65] Governor of North Carolina Beverly Perdue declared a state of emergency for 38 eastern counties on October 26, which took effect on the following day.[66] By October 29, the state of emergency was extended to 24 counties in western North Carolina, with up to a foot of snow attributed to Sandy anticipated in higher elevations. The National Park Service closed at least five sections of the Blue Ridge Parkway.[67]

Virginia

On October 26, Governor of Virginia Bob McDonnell declared a state of emergency. The U.S. Navy sent more than twenty-seven ships and forces to sea from Naval Station Norfolk for their protection.[68] Governor McDonnell authorized the National Guard to activate 630 personnel ahead of the storm.[69] Republican Party presidential candidate Mitt Romney canceled campaign appearances scheduled for October 28 in Virginia Beach, Virginia, and New Hampshire October 30 because of Sandy. Vice President Joe Biden canceled his appearance on October 27 in Virginia Beach and an October 29 campaign event in New Hampshire.[70] President Barack Obama canceled a campaign stop with former President Bill Clinton in Virginia scheduled for October 29, as well as a trip to Colorado Springs, Colorado, the next day because of the impending storm.[71]

Mid-Atlantic

Washington, D.C.

On October 26, Mayor of Washington, D.C. Vincent Gray declared a state of emergency,[72] which President Obama signed on October 28.[73] The United States Office of Personnel Management announced federal offices in the Washington, D.C. area would be closed to the public on October 29–30.[74] In addition, Washington D.C. Metro service, both rail and bus, was canceled on October 29 due to expected high winds, the likelihood of widespread power outages, and the closing of the federal government.[75] The Smithsonian Institution closed for the day of October 29.[76]

Maryland

Governor of Maryland Martin O'Malley declared a state of emergency on October 26.[68] By the following day, Smith Island residents were evacuated with the assistance of the Maryland Natural Resources Police, Dorchester County opened two shelters for those in flood prone areas, and Ocean City initiated Phase I of their Emergency Operations Plan.[77][78][79] Baltimore Gas and Electric Co. put workers on standby and made plans to bring in crews from other states.[80] On October 28, President Obama declared an emergency in Maryland and signed an order authorizing the Federal Emergency Management Agency to aid in disaster relief efforts.[81] Also, numerous areas were ordered to be evacuated including part of Ocean City, Worcester County, Wicomico County, and Somerset County.[82][83] Officials warned that more than a hundred million tons of dirty sediment mixed with tree limbs and debris floating behind Conowingo Dam could be eventually poured into the Chesapeake Bay, posing a potential environmental threat.[84]

The Maryland Transit Administration canceled all service for October 29 and October 30. The cancellations applied to buses, light rail, and Amtrak and MARC train service.[85] On October 29, six shelters opened in Baltimore, and early voting was canceled for the day.[76] Maryland Insurance Commissioner Therese M. Goldsmith activated an emergency regulation requiring pharmacies to refill prescriptions regardless of their last refill date.[86] On October 29, the Chesapeake Bay Bridge over the Chesapeake Bay and the Millard E. Tydings Memorial Bridge and Thomas J. Hatem Memorial Bridge over the Susquehanna River were closed to traffic in the midday hours.[87]

Delaware

On October 28, Governor Markell declared a state of emergency, with coastal areas of Sussex County evacuated.[88] In preparation for the storm, the Delaware Department of Transportation suspended some weekend construction projects, removed traffic cones and barrels from construction sites, and removed several span-wire overhead signs in Sussex County.[89] Delaware Route 1 through Delaware Seashore State Park was closed due to flooding.[88] Delaware roads were closed to the public, except for emergency and essential personnel,[90] and tolls on I-95 and Delaware Route 1 were waived.[91] DART First State transit service was also suspended during the storm.[92]

New Jersey

Preparations began on October 26, when officials in Cape May County advised residents on barrier islands to evacuate. There was also a voluntary evacuation for Mantoloking, Bay Head, Barnegat Light, Beach Haven, Harvey Cedars, Long Beach, Ship Bottom, and Stafford in Ocean County.[93][94][95] Governor of New Jersey Chris Christie ordered all residents of barrier islands from Sandy Hook to Cape May to evacuate and closed Atlantic City casinos. Tolls were suspended on the northbound Garden State Parkway and the westbound Atlantic City Expressway starting at 6 a.m. on October 28.[96] President Obama signed an emergency declaration for New Jersey, allowing the state to request federal funding and other assistance for actions taken before Sandy's landfall.[97]

On October 28, Mayor of Hoboken Dawn Zimmer ordered residents of basement and street-level residential units to evacuate, due to possible flooding.[98] On October 29, residents of Logan Township were ordered to evacuate.[99] Jersey Central Power & Light told employees to prepare to work extended shifts.[80] Most schools, colleges and universities were closed October 29 while at least 509 out of 580 school districts were closed October 30.[100] Although tropical storm conditions were inevitable and hurricane-force winds were likely, the National Hurricane Center did not issue any tropical cyclone watches or warnings for New Jersey, because Sandy was forecast to become extratropical before landfall and thus would not be a tropical cyclone.[101]

Pennsylvania

Preparations in Pennsylvania began when Governor Tom Corbett declared a state of emergency on October 26.[68] Mayor of Philadelphia Michael Nutter asked residents in low-lying areas and neighborhoods prone to flooding to leave their homes by 1800 UTC October 28 and move to safer ground.[102] The Philadelphia International Airport suspended all flight operations for October 29.[103] On October 29, Philadelphia shut down its mass transit system.[76] On October 28, Mayor of Harrisburg Linda D. Thompson declared a state of disaster emergency for the city to go into effect at 5 a.m. October 29. Electric utilities in the state brought in crews and equipment from other states such as New Mexico, Texas, and Oklahoma, to assist with restoration efforts.[104]

New York

Governor Andrew Cuomo declared a statewide state of emergency and asked for a pre-disaster declaration on October 26,[105] which President Obama signed later that day.[106] By October 27, major carriers canceled all flights into and out of JFK, LaGuardia, and Newark-Liberty airports, and the Metro North and Long Island Rail Roads suspended service.[107] The Tappan Zee Bridge was closed,[108] and later the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel and Holland Tunnel were also closed.[109] On Long Island, an evacuation was ordered for South Shore, including areas south of Sunrise Highway, north of Route 25A, and in elevations of less than 16 feet (4.9 m) above sea level on the North Shore.[110] In Suffolk County, mandatory evacuations were ordered for residents of Fire Island and six towns.[111] Most schools closed in Nassau and Suffolk counties on October 29.[112]

New York City began taking precautions on October 26. Governor Cuomo ordered the closure of MTA and its subway on October 28, and the MTA suspended all subway, bus, and commuter rail service beginning at 2300 UTC.[113] After Hurricane Irene nearly submerged subways and tunnels in 2011,[114] entrances and grates were covered just before Sandy, but were still flooded.[115] PATH train service and stations as well as the Port Authority Bus Terminal were shut down in the early morning hours of October 29.[116][117]

Later on October 28, officials activated the coastal emergency plan, with subway closings and the evacuation of residents in areas hit by Hurricane Irene in 2011. More than 76 evacuation shelters were open around the city.[105] On October 29, Mayor Michael Bloomberg ordered public schools closed[116] and called for a mandatory evacuation of Zone A, which comprises areas near coastlines or waterways.[118] Additionally, 200 National Guard troops were deployed in the city.[117] NYU Langone Medical Center canceled all surgeries and medical procedures, except for emergency procedures.[117] Additionally, one of NYU Langone Medical Center's backup generators failed on October 29, prompting the evacuation of hundreds of patients, including those from the hospital's various intensive care units.[119] U.S. stock trading was suspended for October 29–30.[120]

New England

Connecticut Governor Dannel Malloy partially activated the state's Emergency Operations Center on October 26[121] and signed a Declaration of Emergency the next day.[122] On October 28, President Obama approved Connecticut's request for an emergency declaration, and hundreds of National Guard personnel were deployed.[123] On October 29, Governor Malloy ordered road closures for all state highways.[124] Numerous mandatory and partial evacuations were issued in cities across Connecticut.[125]

Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick ordered state offices to be closed October 29 and recommended schools and private businesses close. On October 28, President Obama issued a Pre-Landfall Emergency Declaration for Massachusetts. Several shelters were opened, and many schools were closed.[126] The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority shut down all services on the afternoon of October 29.[127] On October 28, Vermont Governor Peter Shumlin, New Hampshire Governor John Lynch, and Maine's Governor Paul LePage all declared states of emergency.[76][128][129]

Appalachia and the Midwest

The National Weather Service issued a storm warning for Lake Huron on October 29 that called for wave heights of 26 feet (7.9 m), and possibly as high as 38 feet (12 m). Lake Michigan waves were expected to reach 19 feet (5.8 m), with a potential of 33 feet (10 m) on October 30.[130] Flood warnings were issued in Chicago on October 29, where wave heights were expected to reach 18 to 23 feet (5.5 to 7.0 m) in Cook County and 25 feet (7.6 m) in northwest Indiana.[131] Gale warnings were issued for Lake Michigan and Green Bay in Wisconsin until the morning of October 31, and waves of 33 feet (10 m) in Milwaukee and 20 feet (6.1 m) in Sheboygan were predicted for October 30.[132] The actual waves reached about 20 feet (6.1 m) but were less damaging than expected.[133][134] The village of Pleasant Prairie, Wisconsin urged a voluntary evacuation of its lakefront area, though few residents signed up, and little flooding actually occurred.[132][134]

Michigan was impacted by a winter storm system coming in from the west, mixing with cold air streams from the Arctic and colliding with Hurricane Sandy.[130] The forecasts slowed shipping traffic on the Great Lakes, as some vessels sought shelter away from the peak winds, except those on Lake Superior.[135][136] Detroit-based DTE Energy released 100 contract line workers to assist utilities along the eastern U.S. with storm response, and Consumers Energy did the same with more than a dozen employees and 120 contract employees.[137] Due to the widespread power outages, numerous schools had to close, especially in St. Clair County and areas along Lake Huron north of Metro Detroit.[138]

As far as Ohio's western edge, areas were under a wind advisory.[139] All departing flights at Cleveland Hopkins International Airport were canceled until October 30 at 3 p.m.[140]

Governor of West Virginia Earl Ray Tomblin declared a state of emergency ahead of storm on October 29.[141] Up to 2 to 3 feet (0.6–0.9 m) of snow was forecast for mountainous areas of the state.[142]

Canada

The Canadian Hurricane Centre issued its first preliminary statement for Hurricane Sandy on October 25 from Southern Ontario to the Canadian Maritimes,[143] with the potential for heavy rain and strong winds.[144] On October 29, Environment Canada issued severe wind warnings for the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Valley corridor, from Southwestern Ontario as far as Quebec City.[145] On October 30, Environment Canada issued storm surge warnings along the mouth of the St. Lawrence River.[146] Rainfall warnings were issued for the Charlevoix region in Quebec, as well as for several counties in New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia, where about 2 to 3 inches (51 to 76 mm) of rain was to be expected.[147][148][149] Freezing rain warnings were issued for parts of Northern Ontario.[150]

Impact

At least 233 people were killed across the United States, the Caribbean, and Canada, as a result of the storm.[1][2][151][152][153][154][155]

| Region | Fatalities† | Missing | Damage (USD) |

Source(s) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Direct | Indirect | N/A | ||||

| | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Minimal | [1] |

| | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | $100 million | [151][156][157] |

| | 11 | 6 | 0 | 5 | 0 | $2 billion | [2][152][158][159] |

| | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | $30 million | [2][152][160] |

| | 54 | 20 | 0 | 34 | 21 | $750 million | [2][153][161][162][163][164] |

| | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | $100 million | [2][152][165] |

| Offshore of the U.S. | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | [1] |

| | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | [1] |

| | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | $700 million | [2][152][166] |

| | 157 | 71 | 85 | 1 | 0 | $71.4 billion | [13] |

| Totals: | 233 | 106 | 87 | 40 | 21 | ≥$75 billion | |

| Because of differing sources, totals may not match. † Numbers in parentheses indicate direct, indirect and not assigned (due to missing data) deaths. [2] | |||||||

Caribbean

Jamaica

Jamaica was the first country directly affected by Sandy, which was also the first hurricane to make landfall on the island since Hurricane Gilbert, 24 years prior. Trees and power lines were snapped and shanty houses were heavily damaged, both from the winds and flooding rains. More than 100 fishermen were stranded in outlying Pedro Cays off Jamaica's southern coast.[167] Stones falling from a hillside crushed one man to death as he tried to get into his house in a rural village near Kingston.[168] After 6 days another fatality recorded as a 27-year-old man, died due to electrocution, attempting a repair.[2] The country's sole electricity provider, the Jamaica Public Service Company, reported that 70 percent of its customers were without power. More than 1,000 people went to shelters. Jamaican authorities closed the island's international airports, and police ordered 48-hour curfews in major towns to keep people off the streets and deter looting.[169] Most buildings in the eastern portion of the island lost their roofs.[170] Damage was assessed at approximately $100 million throughout the country.[1]

Hispaniola

In Haiti, which was still recovering from both the 2010 earthquake and the ongoing cholera outbreak, at least 54 people died,[161] and approximately 200,000 were left homeless as a result of four days of ongoing rain from Hurricane Sandy.[171] Heavy damage occurred in Port-Salut after rivers overflowed their banks.[172] In the capital of Port-au-Prince, streets were flooded by the heavy rains, and it was reported that "the whole south of the country is underwater".[173] Most of the tents and buildings in the city's sprawling refugee camps and the Cité Soleil neighborhood were flooded or leaking, a repeat of what happened earlier in the year during the passage of Hurricane Isaac.[170] Crops were also wiped out by the storm and the country would be making an appeal for emergency aid.[174] Damage in Haiti was estimated at $750 million (2012 USD), making it the costliest tropical cyclone in Haitian history.[162] In the month following Sandy, a resurgence of Cholera linked to the storm killed at least 44 people and infected more than 5,000 others.[164]

In the neighboring Dominican Republic, two people were killed and 30,000 people evacuated.[152] An employee of CNN estimated 70% of the streets in Santo Domingo were flooded.[175] One person was killed in Juana Díaz, Puerto Rico after being swept away by a swollen river.[152]

Cuba

| Hurricane | Season | Damage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ike | 2008 | $7.3 billion | [176] |

| Matthew | 2016 | $2.58 billion | [177] |

| Gustav | 2008 | $2.1 billion | [176] |

| Michelle | 2001 | $2 billion | [178] |

| Sandy | 2012 | $2 billion | [179] |

| Dennis | 2005 | $1.5 billion | [180] |

| Ivan | 2004 | $1.2 billion | [181] |

| Charley | 2004 | $923 million | [181] |

.jpg)

At least 55,000 people were evacuated before Hurricane Sandy's arrival.[182] While moving ashore, the storm produced waves up to 29 feet (9 meters) and a 6-foot (2 meter) storm surge that caused extensive coastal flooding.[183] There was widespread damage, particularly to Santiago de Cuba where 132,733 homes were damaged, of which 15,322 were destroyed and 43,426 lost their roof.[158] Electricity and water services were knocked out, and most of the trees in the city were damaged. Total losses throughout Santiago de Cuba province is estimated as high as $2 billion (2012 USD).[159] Sandy killed 11 people in the country – nine in Santiago de Cuba Province and two in Guantánamo Province; most of the victims were trapped in destroyed houses.[184][185] This makes Sandy the deadliest hurricane to hit Cuba since 2005, when Hurricane Dennis killed 16 people.[186]

Bahamas

A NOAA automated station at Settlement Point on Grand Bahama Island reported sustained winds of 49 mph (74 km/h) and a wind gust of 63 mph (102 km/h).[187] One person died from falling off his roof while attempting to fix a window shutter in the Lyford Cay area on New Providence. Another died in the Queen's Cove area on Grand Bahama Island where he drowned after the sea surge trapped him in his apartment.[152] Portions of the Bahamas lost power or cellular service, including an islandwide power outage on Bimini. Five homes were severely damaged near Williams's Town.[188] Overall damage in the Bahamas was about $700 million (2012 USD), with the most severe damage on Cat Island and Exuma where many houses were heavily damaged by wind and storm surge.[166]

Bermuda

Owing to the sheer size of the storm, Sandy also impacted Bermuda with high winds and heavy rains. On October 28, a weak F0 tornado touched down in Sandys Parish, damaging homes and businesses.[189] During a three-day span, the storm produced 0.98 in (25 mm) of rain at the L.F. Wade International Airport. The strongest winds were recorded on October 29: sustained winds reached 37 mph (60 km/h) and gusts peaked at 58 mph (93 km/h), which produced scattered minor damage.[190]

United States

| Rank | Hurricane | Season | Damage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Katrina | 2005 | $108 billion | ||

| 2 | Sandy | 2012 | $71.4 billion | ||

| 3 | Ike | 2008 | $29.5 billion | ||

| 4 | Andrew | 1992 | $26.5 billion | ||

| 5 | Wilma | 2005 | $21 billion | ||

| 6 | Ivan | 2004 | $18.8 billion | ||

| 7 | Irene | 2011 | $15.6 billion | ||

| 8 | Charley | 2004 | $15.1 billion | ||

| 9 | Rita | 2005 | $12 billion | ||

| 10 | Matthew | 2016 | $10.6 billion | ||

| Source: National Hurricane Center[191][192][193][nb 1] | |||||

A total of 24 U.S. states were in some way affected by Sandy. The hurricane caused tens of billions of dollars in damage in the United States, destroyed thousands of homes, left millions without electric service,[194] and caused 71 direct deaths in nine states, including 49 in New York, 10 in New Jersey, 3 in Connecticut, 2 each in Pennsylvania and Maryland, and 1 each in New Hampshire, Virginia and West Virginia.[2] There were also 2 direct deaths from Sandy in U.S. coastal waters in the Atlantic Ocean, about 90 miles (150 km) off the North Carolina coast, which are not counted in the U.S. total. In addition, the storm resulted in 87 indirect deaths.[1] In all, a total of 160 people were killed due to the storm, making Sandy the deadliest hurricane to hit the United States mainland since Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and the deadliest to hit the U.S. East Coast since Hurricane Agnes in 1972.[195]

Due to flooding and other storm-related problems, Amtrak canceled all Acela Express, Northeast Regional, Keystone, and Shuttle services for October 29 and 30.[196][197] More than 13,000 flights were canceled across the U.S. on October 29, and more than 3,500 were called off October 30.[198] From October 27 through early November 1, airlines canceled a total of 19,729 flights, according to FlightAware.[199]

On October 31, over 6 million customers were still without power in 15 states and the District of Columbia. The states with the most customers without power were New Jersey with 2,040,195 customers; New York with 1,933,147; Pennsylvania with 852,458; and Connecticut with 486,927.[200]

The New York Stock Exchange and Nasdaq reopened on October 31 after a two-day closure for the storm.[201] More than 1,500 FEMA personnel were along the East Coast working to support disaster preparedness and response operations, including search and rescue, situational awareness, communications and logistical support. In addition, 28 teams containing 294 FEMA Corps members were pre-staged to support Sandy responders. Three federal urban search and rescue task forces were positioned in the Mid-Atlantic and ready to deploy as needed.[202]

On November 2, the American Red Cross announced they have 4,000 disaster workers across storm damaged areas, with thousands more en route from other states. Nearly 7,000 people spent the night in emergency shelters across the region.[203]

Hurricane Sandy: Coming Together, a live telethon on November 2 that featured rock and pop stars such as Bruce Springsteen, Billy Joel, Jon Bon Jovi, Mary J. Blige, Sting and Christina Aguilera, raised around $23 million for American Red Cross hurricane relief efforts.[204]

As of November 5, 2012, the National Hurricane Center ranks Hurricane Sandy the second costliest US hurricane since 1900 in constant 2010 dollars, and the sixth costliest after adjusting for inflation, population and property values.[205] Their report also states that due to global warming the number of future hurricanes will "either decrease or remain essentially unchanged" overall, but the ones that do form will likely be stronger, with fiercer winds and heavier rains.[205]

Scientists at the University of Utah reported the energy generated by Sandy was equivalent to "small earthquakes between magnitudes 2 and 3".[206]

Southeast

Florida

In South Florida, Sandy lashed the area with rough surf, strong winds, and brief squalls. Along the coast of Miami-Dade County, waves reached 10 feet (3.0 m), but may have been as high as 20 feet (6.1 m) in Palm Beach County. In the former county, minor pounding occurred on few coastal roads. Further north in Broward County, State Road A1A was inundated with sand and water, causing more than a 2 miles (3.2 km) stretch of the road to be closed for the entire weekend. Additionally, coastal flooding extended inland up to 2 blocks in some locations and a few houses in the area suffered water damage. In Manalapan, which is located in southern Palm Beach County, several beachfront homes were threatened by erosion. The Lake Worth Pier was also damaged by rough seas. In Palm Beach County alone, losses reached $14 million.[207] Sandy caused closures and cancellations of some activities at schools in Palm Beach, Broward and Miami-Dade counties.[208] Storm surge from Sandy also caused flooding and beach erosion along coastal areas in South Florida.[209] Gusty winds also impacted South Florida, peaking at 67 mph (108 km/h) in Jupiter and Fowey Rocks Light, which is near Key Biscayne.[207] The storm left power outages across the region, which left many traffic lights out of order.[210]

In east-central Florida, damage was minor, though the storm left about 1,000 people without power.[211] Airlines at Miami International Airport canceled more than 20 flights to or from Jamaica or the Bahamas, while some airlines flying from Fort Lauderdale–Hollywood International Airport canceled a total of 13 flights to the islands.[68] The Coast Guard rescued two sea men in Volusia County off New Smyrna Beach on the morning of October 26.[212] Brevard and Volusia Counties schools canceled all extracurricular activities for October 26, including football.[213]

Two panther kittens escaped from the White Oak Conservation Center in Nassau County after the hurricane swept a tree into the fence of their enclosure; they were missing for 24 hours before being found in good health.[214]

North Carolina

On October 28, Governor Bev Perdue declared a state of emergency in 24 western counties due to snow and strong winds.[215]

North Carolina was spared from major damage for the most part (except at the immediate coastline), though winds, rain, and mountain snow affected the state through October 30. Ocracoke and Highway 12 on Hatteras Island were flooded with up to 2 feet (0.6 m) of water, closing part of the highway, while 20 people on a fishing trip were stranded on Portsmouth Island.[216]

There were three Hurricane Sandy-related deaths in the state.[2][217]

On October 29, the Coast Guard responded to a distress call from Bounty, which was built for the 1962 movie Mutiny on the Bounty. It was taking on water about 90 miles (150 km) southeast of Cape Hatteras. Sixteen people were on board.[218] The Coast Guard said the 16 people abandoned ship and got into two lifeboats, wearing survival suits and life jackets.[219] The ship sank after the crew got off.[220] The Coast Guard rescued 14 crew members; another was found hours later but was unresponsive and later died.[221] The search for the captain, Robin Walbridge, was suspended on November 1, after efforts lasting more than 90 hours and covering approximately 12,000 square nautical miles.[222]

Virginia

_(8141816490).jpg)

On October 29, snow was falling in parts of the state.[142] Gov. Bob McDonnell announced on October 30 that Virginia had been "spared a significant event", but cited concerns about rivers cresting leading to flooding of major arteries. Virginia was awarded a federal disaster declaration, with Gov. McDonnell saying he was "delighted" that President Barack Obama and FEMA were on it immediately. At Sandy's peak, more than 180,000 customers were without power, most of whom were located in Northern Virginia.[200][223] There were three Hurricane Sandy-related fatalities in the state.[2][155]

Mid-Atlantic

Maryland and Washington, D.C.

The Supreme Court and the United States Government Office of Personnel Management were closed on October 30,[224][225] and schools were closed for two days.[226] MARC train and Virginia Railway Express were closed on October 30, and Metro rail and bus service were on Sunday schedule, opening at 2 p.m., until the system closes.[227]

At least 100 feet of a fishing pier in Ocean City was destroyed. Governor Martin O'Malley said the pier is "half-gone".[228] Due to high winds, the Chesapeake Bay Bridge and the Millard E. Tydings Memorial Bridge on I-95 were closed.[229] During the storm, the Mayor of Salisbury instituted a Civil Emergency and a curfew.[230] Interstate 68 in far western Maryland and northern West Virginia closed due to heavy snow, stranding multiple vehicles and requiring assistance from the National Guard.[231] Workers in Howard County tried to stop a sewage overflow caused by a power outage October 30. Raw sewage spilled at a rate of 2 million gallons per hour. It was unclear how much sewage had flowed into the Little Patuxent River.[232] Over 311,000 people were left without power as a result of the storm.[200]

Delaware

.jpg)

By the afternoon of October 29, rainfall at Rehoboth Beach totaled 6.53 inches (166 mm). Other precipitation reports include nearly 7 inches (180 mm) at Indian River Inlet and more than 4 inches (100 mm) in Dover and Bear. At 4 p.m. on October 29, Delmarva Power reported on its website that more than 13,900 customers in Delaware and portions of the Eastern Shore of Maryland had lost electric service as high winds brought down trees and power lines. About 3,500 of those were in New Castle County, 2,900 were in Sussex, and more than 100 were in Kent County. Some residents in Kent and Sussex Counties experienced power outages that lasted up to nearly six hours. At the peak of the storm, more than 45,000 customers in Delaware were without power.[200] The Delaware Memorial Bridge speed limit was reduced to 25 mph (40 km/h) and the two outer lanes in each direction were closed. Officials plan to close the span entirely if sustained winds exceed 50 mph (80 km/h). A wind gust of 64 mph (103 km/h) was measured at Lewes just before 2:30 p.m. on October 29, Delaware Route 1 was closed due to water inundation between Dewey Beach and Fenwick Island. In Dewey, flood waters were 1 to 2 feet (0.30 to 0.61 m) in depth.[233] Following the impact in Delaware, President of the United States Barack Obama declared the entire state a federal disaster area, providing money and agencies for disaster relief in the wake of Hurricane Sandy.[234]

New Jersey

A 50-foot piece of the Atlantic City Boardwalk washed away. Half the city of Hoboken flooded; the city of 50,000 had to evacuate two of its fire stations, the EMS headquarters, and the hospital. With the city cut off from area hospitals and fire suppression mutual aid, the city's Mayor asked for National Guard help.[221] In the early morning of October 30, authorities in Bergen County, New Jersey, evacuated residents after a berm overflowed and flooded several communities. Police Chief of Staff Jeanne Baratta said there were up to five feet of water in the streets of Moonachie and Little Ferry. The state Office of Emergency Management said rescues were undertaken in Carlstadt.[235] Baratta said the three towns had been "devastated" by the flood of water.[236] At the peak of the storm, more than 2,600,000 customers were without power.[200] There were 43 Hurricane Sandy-related deaths in the state of New Jersey.[2][237] Damage in the state was estimated at $36.8 billion.[238]

Pennsylvania

Philadelphia Mayor Michael Nutter said the city would have no mass transit operations on any lines October 30.[202] All major highways in and around the city of Philadelphia were closed on October 29 during the hurricane, including Interstate 95, the Blue Route portion of Interstate 476, the Vine Street Expressway, Schuylkill Expressway (I-76), and the Roosevelt Expressway; U.S. Route 1.[239] The highways reopened at 4 a.m. on October 30.[239] The Delaware River Port Authority also closed its major crossings over the Delaware River between Pennsylvania and New Jersey due to high winds, including the Commodore Barry Bridge, the Walt Whitman Bridge, the Ben Franklin Bridge and the Betsy Ross Bridge.[239] Trees and powerlines were downed throughout Altoona, and four buildings partially collapsed.[240] More than 1.2 million were left without power.[76] The Pennsylvania Emergency Management Agency reported 14 deaths believed to be related to Sandy.[241]

New York

New York governor Andrew Cuomo called National Guard members to help in the state. Storm impacts in Upstate New York were much more limited than in New York City; there was some flooding and a few downed trees.[242] Rochester area utilities reported slightly fewer than 19,000 customers without power, in seven counties.[243] In the state as a whole, however, more than 2,000,000 customers were without power at the peak of the storm.[200]

Mayor of New York City Michael Bloomberg announced that New York City public schools would be closed Tuesday, October 30 and Wednesday, October 31, but they remained closed through Friday, November 2.[244] CUNY and NYU canceled all classes and campus activities for October 30.[245] The New York Stock Exchange was closed for trading for two days, the first weather closure of the exchange since 1985.[246] It was also the first two-day weather closure since the Great Blizzard of 1888.[247]

The East River overflowed its banks, flooding large sections of Lower Manhattan. Battery Park had a water surge of 13.88 ft.[248] Seven subway tunnels under the East River were flooded.[249] The Metropolitan Transportation Authority said that the destruction caused by the storm was the worst disaster in the 108-year history of the New York City subway system.[250] Sea water flooded the Ground Zero construction site.[251] Over 10 billion gallons of raw and partially treated sewage were released by the storm, 94% of which went into waters in and around New York and New Jersey.[252] In addition, a four story Chelsea building's facade crumbled and collapsed, leaving the interior on full display; however, no one was hurt by the falling masonry.[253] The Atlantic Ocean storm surge also caused considerable flood damage to homes, buildings, roadways, boardwalks and mass transit facilities in low-lying coastal areas of the outer boroughs of Queens, Brooklyn and Staten Island.

After receiving many complaints that holding the marathon would divert needed resources, Mayor Bloomberg announced late afternoon November 2 that the New York City Marathon had been canceled. The event was to take place on Sunday, November 4. Marathon officials had said that they did not plan to reschedule.[254]

Gas shortages throughout the region led to an effort by the U.S. federal government to bring in gasoline and set up mobile truck distribution at which people could receive up to 10 gallons of gas, free of charge. This caused lines of up to 20 blocks long and was quickly suspended.[255] On Thursday, November 8, Mayor Bloomberg announced odd-even rationing of gasoline would be in effect beginning November 9 until further notice.[256]

On November 26, Governor Cuomo called Sandy "more impactful" than Hurricane Katrina, and estimated costs to New York at $42 billion.[257]

The storm severely damaged or destroyed around 100,000 homes on Long Island with more than 2,000 homes deemed uninhabitable there.[258]

There were 71 Hurricane Sandy-related deaths in the state of New York.[2] In 2016, a new scientific analysis determined that Sandy was the worst hurricane to strike the New York City area since at least 1700.[259]

New England

Wind gusts to 83 mph were recorded on outer Cape Cod and Buzzards Bay.[260] Nearly 300,000 customers were without power in Massachusetts,[200] and roads and buildings were flooded.[261] Over 100,000 customers lost power in Rhode Island.[262] Most of the damage was along the coastline, where some communities were flooded.[263] Mount Washington, New Hampshire saw the strongest measured wind gust from the storm at 140 mph.[264] Nearly 142,000 customers lost power in the state.[200]

Appalachia and Midwest

West Virginia

Sandy's rain became snow in the Appalachian mountains, leading to blizzard conditions in some areas, especially West Virginia,[1] when a tongue of dense and heavy Arctic air pushed south through the region. This would normally cause a Nor'easter, prompting some to dub Sandy a "nor'eastercane" or "Frankenstorm".[265] There was 1–3 feet (30–91 cm) of snowfall in 28 of West Virginia's 55 counties.[1][266] The highest snowfall accumulation was 36 inches (91 cm) near Richwood.[1] Other significant totals include 32 inches (81 cm) in Snowshoe, 29 inches (74 cm) in Quinwood,[267] and 28 inches (71 cm) in Davis, Flat Top, and Huttonsville.[268] By the morning of October 31, there were still 36 roads closed due to downed trees, powerlines, and snow in the road.[267] Approximately 271,800 customers lost power during the storm.[200]

There were reports of collapsed buildings in several counties due to the sheer weight of the wet, heavy snow.[269] Overall, there were seven fatalities related to Hurricane Sandy and its remnants in West Virginia,[270] including John Rose, Sr., the Republican candidate for the state's 47th district in the state legislature, who was killed in the aftermath of the storm by a falling tree limb broken off by the heavy snowfall.[271] Governor Earl Ray Tomblin asked President Obama for a federal disaster declaration, and on October 30, President Obama approved a state of emergency declaration for the state.[272]

Ohio

Wind gusts at Cleveland Burke Lakefront Airport were reported at 68 miles per hour (109 km/h).[273] On October 30, hundreds of school districts canceled or delayed school across the state with at least 250,000 homes and businesses without power.[274] Damage was reported across the state including the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame which lost parts of its siding.[273] Snow was reported in some parts of eastern Ohio and south of Cleveland. Snow and icy roads also were reported south of Columbus.[274]

Michigan

The US Department of Energy reported that more than 120,000 customers lost power in Michigan as a result of the storm.[200] The National Weather Service said that waves up to 23 feet high were reported on southern Lake Huron.[138]

Kentucky

More than a foot of snow fell in eastern Kentucky as Sandy merged with an Arctic front.[275] Winter warnings in Harlan, Letcher, and Pike County were put into effect until October 31.[276]

Canada

The remnants of Sandy produced high winds along Lake Huron and Georgian Bay, where gusts were measured at 105 km/h (63 mph). A 121 km/h (72 mph) gust was measured on top of the Bluewater Bridge.[277] One woman died after being hit by a piece of flying debris in Toronto.[151] At least 145,000 customers across Ontario lost power,[278] and a Bluewater Power worker was electrocuted in Sarnia while working to restore power.[279] Around 49,000 homes and businesses lost power in Quebec during the storm, with nearly 40,000 of those in the Laurentides region of the province, as well as more than 4,000 customers in the Eastern Townships and 1,700 customers in Montreal.[280] Hundreds of flights were canceled.[281] Around 14,000 customers in Nova Scotia lost power during the height of the storm.[282] The Insurance Bureau of Canada's preliminary damage estimate was over $100 million for the nation.[157]

Aftermath

Relief efforts

Several organizations have contributed to the hurricane relief effort. Disney–ABC Television Group held a "Day of Giving" on Monday, November 5, raising $17 million on their television stations for the American Red Cross.[283] NBC raised $23 million during their Hurricane Sandy: Coming Together telethon.[284] News Corporation donated $1 million to relief efforts in the New York metropolitan area.[285] Much of the funding raised in New Jersey was distributed by the NGO, Hurricane Sandy New Jersey Relief Fund.[286]

The United Nations and World Food Programme said they would send humanitarian aid to at least 500,000 people in Santiago de Cuba.[287]

On December 3, it was announced that 12-12-12: The Concert for Sandy Relief would take place December 12, 2012 at Madison Square Garden in New York City. Various television channels in the United States and internationally aired the four-hour concert which is expected to reach over 1 billion people worldwide. The concert featured performances by Bon Jovi, Eric Clapton, Dave Grohl, Billy Joel, Alicia Keys, Chris Martin, Paul McCartney, The Rolling Stones, Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band, Roger Waters, Eddie Vedder, Kanye West, and The Who. Web sites including Fuse.tv, MTV.com, YouTube, and the sites of AOL and Yahoo! planned to stream the performance.[288]

On December 28, 2012, the Senate approved an emergency relief bill to provide $60 billion for states affected by Sandy,[289] but the House (in effect) postponed action until the next session (which began January 3) by adjourning without voting on the bill.[290] House leaders pledged to vote on a flood insurance bill on January 4, 2013 and to vote on an aid package by January 15.[291] On January 28, the Senate passed the $50.5 billion Sandy aid bill by a count of 62–36.[292] President Obama signed the bill into law January 29.[293]

On January 21, 2013, The New York Times reported that those affected by the hurricane were still struggling to recover.[294]

In June 2013—following the occurrence of Hurricane Irene, Tropical Storm Lee and most recently Hurricane Sandy—Governor Andrew Cuomo set out to centralize recovery and rebuilding efforts in impacted areas of New York State. Establishing the Office of Storm Recovery, the Governor aimed to address communities' most urgent needs, while also encouraging the identification of innovative and enduring solutions to strengthen the State's infrastructure and critical systems. Operating under the umbrella of New York Rising, the Governor's Office of Storm Recovery (GOSR) utilizes approximately $3.8 billion in flexible funding made available by the U.S. Department of Housing & Urban Development's (HUD) Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) program to concentrate aid in four main areas: Housing, Small Business, Infrastructure, and the Community Reconstruction Program.[295]

As of March 2014, the New York Rising Community Reconstruction Program had distributed more than $280 million in payments to 6,388 homeowners for damage that resulted from Hurricane Sandy, Hurricane Irene or Tropical Storm Lee. Every eligible homeowner who applied by January 20 had been issued a check for home reconstruction. Over 4,650 Nassau residents had been issued rebuilding payments totaling over $201 million and over 1,350 Suffolk residents had been issued over $65 million in rebuilding payments. Additionally through its buyout and acquisition program, the State had made offers totaling over $293 million to purchase the homes of 709 homeowners.[296]

On December 6, 2013, an analysis of data provided by the Federal Emergency Management Agency showed that fewer than half of those affected who requested disaster recovery assistance had received any. As of that date, 30,000 residents of New York and New Jersey remained displaced.[297]

On March 18, 2014, Newsday reported that 17 months after the hurricane those who were displaced from rental units on Long Island faced unique difficulties due to the lack of affordable rental housing and delays in housing program implementations by New York State. The New York State Governor's Office of Storm Recovery reported that close to 9,000 rental units on Long Island were damaged by Hurricane Sandy in October 2012, as well as by Hurricane Irene and Tropical Storm Lee in 2011.[298] New York State officials said that additional assistance would soon be available from Community Development Block Grant funds provided by the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development via the New York Rising program.[299] On March 15, 2014, a group of those who remained displaced by the hurricane organized a protest at the Nassau Legislative building in Mineola, New York, to raise awareness of their frustrations with the timeline for receiving financial assistance from the New York Rising program.[300]

Political impact

Hurricane Sandy sparked much political commentary. Many scientists say warming oceans and greater atmospheric moisture are intensifying storms while rising sea levels are worsening coastal effects. Representative Henry Waxman of California, the top Democrat of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, requested a hearing in the lame duck session on links between climate change and Hurricane Sandy.[301] Some news outlets labeled the storm the October surprise of the 2012 United States Presidential election,[302][303] while Democrats and Republicans accused each other of politicizing the storm.[304]

The storm, which hit the United States one week before its general election, affected the presidential campaign as well as local and state campaigns in storm-damaged areas. New Jersey Governor Chris Christie, one of Mitt Romney's leading supporters, praised President Barack Obama and his reaction to the hurricane and toured storm-damaged areas of his state with the president.[305] It was reported at the time that Sandy might affect elections in several states, especially by curtailing early voting.[306] The Economist said, "In this case, the weather is supposed to clear up well ahead of election day, but the impact could be felt in the turnout of early voters."[307] However, ABC News said this might be offset by a tendency to clear roads and restore power more quickly in urban areas.[308] The storm ignited a debate over whether Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney in 2011 proposed to eliminate the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).[309] The Romney campaign eventually issued a statement promising to keep FEMA funded but did not explain what other parts of the federal budget he would cut to pay for it.[310] Beyond the election, National Defense Magazine said Sandy "might cause a rethinking (in the USA) of how climate change threatens national security".[311]

In his news conference on November 14, President Obama said "... we can't attribute any particular weather event to climate change. What we do know is the temperature around the globe is increasing faster than was predicted even 10 years ago. We do know that the Arctic ice cap is melting faster than was predicted even five years ago. We do know that there have been extraordinarily — there have been an extraordinarily large number of severe weather events here in North America, but also around the globe. And I am a firm believer that climate change is real, that it is impacted by human behavior and carbon emissions. And as a consequence, I think we've got an obligation to future generations to do something about it."[312]

On January 30, 2015, days after the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers released a post-Sandy report examining flood risks for 31,200 miles of the North Atlantic coast, President Obama issued an executive order directing federal agencies — as well as state and local governments drawing on federal funds — to adopt stricter building and siting standards to reflect scientific projections that future flooding will be more frequent and intense due to climate change.[313]

Financial markets impact

The New York Stock Exchange and other financial markets were closed on both October 29 and 30 as a result of Hurricane Sandy, due to power outages and flooding in the area. Such a closure for weather-related reasons had not happened since 1888.[314] The markets reopened on October 31, and to the relief of investors, closed relatively flat that day. A week later, the National Association of Insurance Commissioners Capital Markets Bureau noted a slight uptick in the market (0.8%) and suggested that the negative economic impact of Hurricane Sandy was offset by the expected positive impacts of rebuilding.[315]

Media coverage

As Hurricane Sandy approached the United States, forecasters and journalists gave it several different unofficial names, at first related to its projected snow content, then to its proximity to Halloween, and eventually to the overall size of the storm. Early nicknames included "Snowicane Sandy"[316] and "Snor'eastercane Sandy".[317][318] The most popular Halloween-related nickname was "Frankenstorm",[319][320] coined by Jim Cisco, a forecaster at the Hydrometeorological Prediction Center.[321][322][323] CNN banned the use of the term, saying it trivialized the destruction.[324][325]

The severe and widespread damage the storm caused in the United States, as well as its unusual merger with a frontal system, resulted in the nicknaming of the hurricane "Superstorm Sandy" by the media, public officials, and several organizations, including U.S. government agencies.[326][327][328][329][330][331][332] This persisted as the most common nickname well into 2013.[333][334] The term was also embraced by climate change proponents as a term for the new type of storms caused by global warming,[335] while other writers used the term but maintained that it was too soon to blame the storm on climate change.[336][337] Meanwhile, Popular Science called it "an imaginary scare-term that exists exclusively for shock value".[338]

Insurance fraud claims

Thousands of homeowners were denied their flood insurance claims based upon fraudulent engineers' reports, according to the whistleblowing efforts of Andrew Braum, an engineer who claimed that at least 175 of his more than 180 inspections were doctored.[339][340] As a result, a class-action racketeering lawsuit has been filed against several insurance companies and their contract engineering firms.[341] Further, the Federal Emergency Management Agency plans to review all flood insurance claims in light of these allegations.[342]

Baby boom

New Jersey hospitals saw a spike in births nine months after Sandy, causing some to believe that there was a post-Sandy baby boom. The Monmouth Medical Center saw a 35% jump, and two other hospitals saw 20% increases.[343] An expert stated that post-storm births that year were higher than in past disasters.[344]

Retirement of the name

Because of the exceptional damage and deaths caused by the storm in many countries, the name Sandy was later retired by the World Meteorological Organization, and will never be used again for a North Atlantic hurricane. The name was replaced with Sara for the 2018 Atlantic hurricane season.[345]

In popular culture

In the Syfy television movie Sharknado 3: Oh Hell No!, a radar image of Sandy can be seen (close to its landfall in New Jersey), but represented fictionally as an unnamed tropical storm heading towards Washington D.C.

See also

- 1938 New England hurricane

- 1991 Perfect Storm

- Hurricane Sandy IRS tax deduction

- List of Atlantic hurricane records

- List of New Jersey hurricanes

- List of New York hurricanes

- Shored Up, a documentary about the storm

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Blake, Eric S; Kimberlain, Todd B; Berg, Robert J; Cangialosi, John P; Beven II, John L; National Hurricane Center (February 12, 2013). Hurricane Sandy: October 22 – 29, 2012 (PDF) (Tropical Cyclone Report). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Archived from the original on February 17, 2013. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Diakakis M.; Deligiannakis G.; Katsetsiadou K.; Lekkas E. (2015). "Hurricane Sandy mortality in the Caribbean and continental North America". Disaster Prevention and Management: an International Journal. 24 (1): 132. doi:10.1108/DPM-05-2014-0082.

- ↑ "Sandy Brings Hurricane-Force Gusts After New Jersey Landfall". Washington Post. Retrieved 2012-10-30.

- ↑ "Hurricane Sandy Grows To Largest Atlantic Tropical Storm Ever". WBZ-TV. Retrieved 2013-01-07.

- ↑ Hurricane/Post-Tropical Cyclone Sandy, October 22–29, 2012 (PDF) (Service Assessment). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. May 2013. p. 10. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved June 2, 2013.

- ↑ Cumulative total of death toll by country; see chart.

- ↑ "Hurricane Sandy storms through Bahamas, Central Florida on alert". Central Florida News 13. Retrieved 2012-10-26.

- ↑ "Post-Tropical Cyclone SANDY Update Statement". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on November 1, 2012. Retrieved 2012-10-29.

- ↑ "Sandy wreaks havoc across Northeast; at least 11 dead". CNN. 2012-10-30.

- ↑ "Sandy caused $100M in Canadian insurance claims". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 2012-11-28.

- ↑ "Superstorm Sandy causes at least 9 U.S. deaths as it slams East Coast", CNN

- ↑ "Eli Manning deals with Superstorm Sandy flooding". National Football League. 2012-10-31. Retrieved 2012-10-31.

- 1 2 "The thirty costliest mainland United States tropical cyclones 1900-2013". Hurricane Research Division. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2014. Retrieved September 10, 2015.

- 1 2 Robbie Berg; Lixion Avila (2012-10-22). Tropical Depression Eighteen Discussion Number 1 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2012-10-23.

- ↑ Richard Pasch (2012-10-22). Tropical Storm Sandy Discussion Number 2 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2012-10-23.

- ↑ Jack Beven (2012-10-24). Tropical Storm Sandy Discussion Number 7 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2012-10-24.

- ↑ Michael Brennan (2012-10-24). Hurricane Sandy Discussion Number 9 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2012-10-24.

- ↑ Todd Kimberlain; James Franklin (2002-10-24). Hurricane Sandy Tropical Cyclone Update (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2012-10-24.

- ↑ Stacy Stewart; Dave Roberts (October 25, 2012). Hurricane Sandy Tropical Cyclone Update (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2012-10-26.

- ↑ Michael Brennan (2012-10-25). Hurricane Sandy Discussion Number 14 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2012-10-26.

- ↑ Jack Beven (2012-10-26). Hurricane Sandy Discussion Number 15 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2012-10-26.

- ↑ Jack Beven (2012-10-27). Hurricane Sandy Discussion Number 19 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2012-10-27.

- ↑ Jack Beven (2012-10-27). Tropical Storm Sandy Discussion Number 20 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2012-10-27.

- ↑ Daniel Brown (2012-10-27). Hurricane Sandy Discussion Number 21 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2012-10-27.

- ↑ Stacy Stewart (2012-10-29). Hurricane Sandy Discussion Number 25 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2012-10-31.

- ↑ Richard Pasch; John Cangialosi (2012-10-29). Hurricane Sandy Discussion Number 28 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2012-10-31.

- ↑ Stacy Stewart (2012-10-29). Hurricane Sandy Discussion Number 29 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2012-10-31.

- ↑ Richard Knabb; James Franklin (2012-10-29). Hurricane Sandy Discussion Number 30 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2012-10-31.

- ↑ Daniel Brown; Dave Roberts (2012-10-29). Post-Tropical Cyclone Sandy Tropical Cyclone Update (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2012-10-31.

- ↑ Daniel Brown; Dave Roberts (2012-10-30). Post-Tropical Cyclone Sandy Tropical Cyclone Update (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2012-10-31.

- ↑ Vergano, Dan (2012-10-30). "U.S. forecast's late arrival stirs weather tempest". USA Today. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- ↑ Trenberth, Kevin (March 2012). "Framing the way to relate climate extremes to climate change" (PDF). Climatic Change. 115 (2): 283–290. doi:10.1007/s10584-012-0441-5.

- 1 2 Andrew C., Revkin (2012-10-28). "The #Frankenstorm in Climate Context". The New York Times; Dot Earth.

- 1 2 3 Trenberth, Kevin. "Hurricane Sandy mixes super-storm conditions with climate change". The Conversation. Retrieved 2012-10-29.

The sea surface temperatures along the Atlantic coast have been running at over 3°C above normal for a region extending 800 km off shore all the way from Florida to Canada. Global warming contributes 0.6°C to this. With every degree C, the water holding of the atmosphere goes up 7%, and the moisture provides fuel for the tropical storm, increases its intensity, and magnifies the rainfall by double that amount compared with normal conditions. Global climate change has contributed to the higher sea surface and ocean temperatures, and a warmer and moister atmosphere, and its effects are in the range of 5 to 10%. Natural variability and weather has provided the perhaps optimal conditions of a hurricane running into extra-tropical conditions to make for a huge intense storm, enhanced by global warming influences.

- 1 2 3 Masters, Jeff. "Why did Hurricane Sandy take such an unusual track into New Jersey?". Weather Underground. Retrieved 2012-11-06.

- ↑ Fischetti, Mark (October 30, 2012). "Did Climate Change Cause Hurricane Sandy?".

- ↑ Velasquez-Manoff, Moises (9 November 2006). "How to keep New York afloat". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2012-12-15.

- ↑ Boxall and Neela Banerjee, Bettina (4 November 2012). "Sandy a galvanizing moment for climate change?". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2012-11-05.

- ↑ Mason, Edward (6 November 2012). "Hello again, climate change". Harvard Gazette. Retrieved 2012-11-07."He pointed out that since 2007, melted Arctic ice opened the Northwest Passage, a development that he believes could have a dramatic effect on weather patterns. Last spring's unseasonable warmth caused places like Rochester, Minn., to set record daytime highs. 'By midcentury, this will be the new normal,' Schrag predicted. 'How do you deal with extreme heat in the summer? It's going to be a challenge, but humans are adaptable. It's not going to be easy, just like a 13-foot storm surge will be the new norm on the Eastern seaboard.'"

- ↑ Robbie Berg; Lixion Avila (2012-10-22). Tropical Depression Eighteen Advisory Number 1 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2012-10-24.

- ↑ Daniel Brown (2012-10-23). Tropical Storm Sandy Advisory Number 4 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2012-10-24.

- 1 2 3 Richard Pasch (2012-10-23). Tropical Storm Sandy Advisory Number 5 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2012-10-24.

- ↑ McFadden, David (October 23, 2012). "Jamaica prepares for Tropical Storm Sandy". Associated Press. Retrieved 2012-11-26.

- ↑ Richard Pasch (2012-10-22). Tropical Storm Sandy Advisory Number 2 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2012-10-24.

- ↑ Richard Pasch (2012-10-23). Tropical Storm Sandy Advisory Number 5A (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2012-10-24.

- 1 2 Richard Pasch (2012-10-23). Tropical Storm Sandy Advisory Number 6 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2012-10-24.

- ↑ John Beven II (2012-10-24). Tropical Storm Sandy Advisory Number 7 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2012-10-24.

- ↑ Richard Pasch (2012-10-26). Hurricane Sandy Tropical Cyclone Update (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2012-10-26.

- ↑ Associated Press (October 25, 2012). "Forecasters warn East Coast about 'Frankenstorm' next week; damage could top $1 billion". FoxNews.com. Retrieved 2013-10-04.

- ↑ Borenstein, Seth. "East Coast braces for monster 'Frankenstorm'". Associated Press. Retrieved 2012-10-26.

- ↑ Cisco, Jim (25 October 2012). "Extended Forecast Discussion – Issued 1342Z Oct 25, 2012". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved 2012-10-26.

- ↑ Borenstein, Seth (25 October 2012). "Forecasters warn East Coast about 'Frankenstorm' next week; damage could top $1 billion". The Washington Post. Associated Press. Retrieved 2012-10-26.

- ↑ "Hurricane Sandy: Five Reasons It's a Superstorm". Fox News. Associated Press. October 29, 2012. Retrieved 2012-10-29.

- ↑ Day, Patrick Kevin (October 26, 2012). "No 'Frankenstorm' for CNN". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2013-01-21. Retrieved 2012-10-29.

- ↑ Samenow, Jason (2012-10-28). "Cause for concern: the 7 most alarming Hurricane Sandy images". Washington Post. Retrieved 2012-10-28.

- ↑ Anderson, Lars (2012-10-25). "Closely Monitoring Hurricane Sandy". FEMA. Retrieved 2012-10-26.

- ↑ "It's watch and wait as Hurricane Sandy approaches". News.blogs.cnn.com. 2012-10-28. Retrieved 2012-10-29.

- ↑ "Hurricane Sandy wreaks havoc on airline flights". The Wall St. Journal. Retrieved 2012-10-28.

- ↑ "Hurricane Sandy Flight Cancellations: Thousands Of Flights Canceled Due To Storm". Huffingtonpost.com. 2012-10-28. Retrieved 2012-10-29.

- ↑ "Amtrak begins to cancel some service in advance of Hurricane Sandy". Amtrak. Retrieved 2012-10-28.

- ↑ Sullivan, Brian K; Hart, Dan (2012-10-28). "Hurricane Sandy Barrels Northward, May Hit New Jersey". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2012-10-28.

- ↑ Man, Karl; Smith, Scott T.; Wright, Michele. "UPDATED: Hurricane Sandy closings and cancellations". WPEC-TV. Retrieved 2012-10-25.

- ↑ Gertz, Bill (2012-11-05). "Russian Sub Skirts Coast". Washington Free Beacon. Center for American Freedom. Archived from the original on November 6, 2012. Retrieved 2012-11-05.

- ↑ Michael Brennan (October 26, 2012). Hurricane Sandy Advisory Number 16 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2012-12-13.

- ↑ Richard Pasch (October 26, 2012). Hurricane Sandy Advisory Number 18 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2012-12-13.

- ↑ "Perdue declares state of emergency before Sandy arrives". WRAL.com. Retrieved 2012-10-26.

- ↑ "Perdue declares state of emergency for Western NC". WRAL.com. Retrieved 2012-10-29.

- 1 2 3 4 "Northeast in crosshairs of 'superstorm' Sandy". CNN. 2012-10-27. Retrieved 2012-10-26.

- ↑ "National Guard soldiers activated for Hurricane Sandy". Army Times. Retrieved 2012-10-31.

- ↑ "Hurricane Sandy scrambles campaign schedule, Romney cancels Virginia rallies". Fox News. 2012-10-27. Retrieved 2012-10-28.

- ↑ "Obama cancels stops in Virginia, Colorado because of storm". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on October 30, 2012. Retrieved 2012-10-28.

- ↑ "District Government Prepares for Hurricane Sandy". DC.gov. October 26, 2012. Retrieved 2012-12-13.

- ↑ "Pres. Obama Signs D.C. Emergency Declaration". CBS DC. Associated Press. October 28, 2012. Retrieved 2012-12-13.

- ↑ "Federal Government Operating Status Washington D.C. Area". Retrieved 2012-10-29.

- ↑ Weil, Martin (2012-10-28). "Metro system to shut down on Monday". Washington Post. Retrieved 2012-10-28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "A state-by-state look at the East Coast superstorm". AP. Retrieved 2012-10-29.

- ↑ "Smith Island Evacuations Under Way". WBOC. Retrieved 2012-10-27.

- ↑ "Dorchester County Offering Shelter During Hurricane Sandy". WBOC. Retrieved 2012-10-27.

- ↑ "O.C. Implementing Phase I of Emergency Operations Plan". WBOC. Retrieved 2012-10-27.

- 1 2 "Eastern utilities brace for expected super storm". The Washington Examiner. Retrieved 2012-10-26.

- ↑ "Obama Signs Maryland Emergency Declaration". WBOC. Retrieved 2012-10-28.

- ↑ "Worcester County Issues Mandatory Evacuations". WMDT. Retrieved 2012-10-28.

- ↑ "Ocean City Declares Local State Of Emergency". WMDT. Retrieved 2012-10-28.

- ↑ Fears, Darryl (October 27, 2012). "Sandy poses environmental threat to Conowingo Dam". Washington Post.

- ↑ "MTA Suspends Bus & Train Service On Monday; BWI Delaying & Canceling Flights Due To Hurricane Sandy". CBS News Baltimore. Retrieved 2012-10-29.

- ↑ "Insurance Commissioner Issues Emergency Regulation Regarding Prescriptions, Pharmacy Payments". Maryland Insurance Administration. Retrieved 2012-10-28.

- ↑ "Chesapeake Bay Bridge Now Closed". WBOC TV. Retrieved 2012-10-29.

- 1 2 "Sussex County Update on Hurricane Sandy". WBOC-TV. October 28, 2012. Retrieved 2012-10-28.

- ↑ "DelDOT is preparing for a possible major storm". Delaware Department of Transportation. October 26, 2012. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ↑ "Delaware roads closed to public after 5 a.m". 6 Action News. Retrieved 2012-10-29.

- ↑ "Tolls Waived on I-95 and Route One". State of Delaware. Retrieved 2012-10-29.

- ↑ "DART & Paratransit Service Suspended Monday". Delaware Department of Transportation. October 28, 2012. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ↑ Staff (October 27, 2012). "Ocean County towns issue voluntary evacuations". Asbury Park Press. Retrieved 2012-10-27.

- ↑ "Shore towns issue voluntary evac orders". ABC7. October 26, 2012. Retrieved 2012-10-26.

- ↑ Denise DiStephan (October 26, 2012). "Bay Head and Mantoloking Advising Voluntary Evacuations. Mantoloking police department urging residents to leave ahead of Sandy". Point Pleasant Patch. Retrieved 2012-10-27.

- ↑ "Christie Declares State of Emergency; Orders Evacuations In Some Parts of N.J". CBS2. October 27, 2012. Retrieved 2012-10-27.

- ↑ "President signs emergency declaration for NJ". Newsday. Retrieved 2012-10-29.

- ↑ "Hoboken mayor announces evacuation of all basements and street-level residences". NewJersey.com. Retrieved 2012-10-29.

- ↑ "Hurricane Sandy: Parts of Logan Township issued evacuation order".