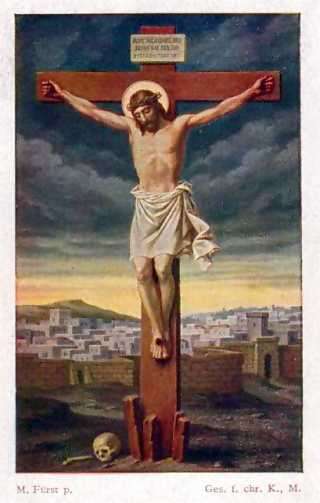

Holy card

In the Christian tradition, holy cards or prayer cards are small, devotional pictures mass-produced for the use of the faithful. They usually depict a religious scene or a saint in an image about the size of a playing card. The reverse typically contains a prayer, some of which promise an indulgence for its recitation. The circulation of these cards is an important part of the visual folk culture of Roman Catholics, and in modern times, prayer cards have been also become popular among Orthodox Christians and Protestant Christians, although with the latter, biblical themes are emphasized within them.[1][2]

Old master prints

Old master prints, nearly all on religious subjects, served many of the same functions as holy cards, especially the cheaper woodcuts; the earliest dated surviving example is from 1423, probably from southern Germany, and depicts Saint Christopher, with handcolouring, it is found as part of the binding of a manuscript of the Laus Virginis (1417) which belongs to the John Rylands Library, Manchester.[3][4] Later engraving or etching were more commonly used. Some had elaborate borders of paper lace surrounding the images; these were called dévotes dentelles in France.

Lithography

The invention of colour lithography made it possible to reproduce coloured images cheaply, leading to a much broader circulation of the cards. An early centre of their manufacture was in the environs of the Church of St Sulpice in Paris; the lithographed images made there were done in delicate pastel colours, and proved extremely influential on later designs. Belgium and Germany also became centres of the manufacture of holy cards, as did Italy in the twentieth century. Catholic printing houses (such as Maison de la Bonne Presse in France and Ars Sacra in Germany) produced large numbers of cards, and often a single design was printed by different companies in different countries.

Special types of cards

Special holy cards are printed for Roman Catholics to be distributed at funerals; these are "In memoriam cards", with details and often a photograph of the person whom they commemorate as well as prayers printed on the back. Other specialized holy cards record baptisms, confirmations, and other religious anniversaries. Others are not customized, and are circulated to promote the veneration of the saints and images they bear.

At the end of the nineteenth century, some Protestants also produced similar images of their own. They produced Bible cards or Sunday school cards, with lithographed illustrations depicting Bible stories and parables, more modern scenes of religious life or prayer, or sometimes just a Biblical text illuminated by calligraphy; these were linked to Biblical passages that related to the image. The reverse typically held a sermonette instead of a prayer. Imagery here was always the servant of text, and as such these Protestant cards tended to be replaced by tracts that emphasized message instead of imagery, and were illustrated with cartoon-like images if they were illustrated at all.

World War II and the Cold War

The Head of Christ painting has been printed more than 500 million times, including pocket-sized cards for carrying in a wallet.[5] In the World War II era, "millions of cards featuring the Head of Christ were distributed through the USO by the Salvation Army and the YMCA to members of the American armed forces stationed overseas".[6] During the Cold War, both Catholics and Protestants helped to popularize these cards, presenting "a united front against the menace of godless Communism".[7]

Irish law of 2009

In Ireland, cards are sold certifying that a Mass has been said for the benefit of sick or dead people, and are typically given to the family of the sick or dead person. Disputes arose over the validity of cards issued by priests living outside Ireland. Section 99 of the 2009 Charities Act regulates sales of Mass Cards, which can only be sold "pursuant to an arrangement" with a "recognised person", such as a Bishop, without stipulating whether that person had to be resident in Ireland or not.[8] A court challenge to the new law by a business that sold 120,000 cards a year failed in late 2009.[9] A breach of the law can result in a 10-year prison sentence or a €300,000 fine.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Holy card. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bible cards. |

References

- ↑ Hasinoff, Erin L. (2011-11-22). Faith in Objects: American Missionary Expositions in the Early Twentieth Century. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 206. ISBN 9780230339729.

Protestant prayer cards tended to emphasize biblical themes as opposed to devotional subjects (Leonard Primiano, personal communication, 2011).

- ↑ Illes, Judika (2011-10-11). Encyclopedia of Mystics, Saints & Sages. HarperCollins. p. 68. ISBN 9780062098542.

In recent years, holy cards have become increasingly popular among Orthodox Christians as well.

- ↑ "Incunabula". Guide to Special Collections. John Rylands University Library. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- ↑ John Rylands Library (1969) Catalogue of an Exhibition of Manuscripts and Early Printing Originating in Germany. Manchester: John Rylands Library; p. 15 (gives references to Dodgson: Woodcuts; 2 & Schreiber: Manuel; 1349)

- ↑ Lippy, Charles H. (1 January 1994). Being Religious, American Style: A History of Popular Religiosity in the United States. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 185. ISBN 9780313278952. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

Of these one stands out as having deeply impressed itself of the American religious consciousness: the "Head of Christ" by artist Warner Sallman (1892-1968). Originally sketched in charcoal as a cover illustration for the Covenant Companion, the magazine of the Swedish Evangelical Mission Covenant of America denomination, and based on an image of Jesus in a painting by the French artist Leon Augustin Lhermitte, Sallman's "Head of Christ" was painted in 1940. In half a century, it had been produced more than five hundred million times in formats ranging from large-scale copies for use in churches to wallet-sized ones that individuals could carry with them at all times.

- ↑ Moore, Stephen D. (2001). God's Beauty Parlor. Stanford University Press. p. 248. ISBN 9780804743327.

- ↑ Prothero, Stephen (15 December 2003). American Jesus: How the Son of God Became a National Icon. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 117. ISBN 9780374178901.

During the postwar revival of the 1940s and 1950s, as Protestants and Catholics downplayed denominational differences in order to present a united front against the menace of godless Communism, Sallman's Jesus became far and away the most common image of Jesus in American homes, churches, and workplaces. Thanks to Sallman (and the savvy marketing of his distributors), Jesus became instantly recognizable by Americans of all races and religions.

- ↑ Charities Act 2009 text

- ↑ McNally case; accessed from RTE website August 2010

Further reading

- Ball, Ann Encyclopedia of Catholic Devotions and Practices.

- Gärtner, Hans (2004) Andachtsbildchen: Kleinode privater Frömmigkeitskultur. München: Verlag Sankt Michaelsbund ISBN 3-920821-45-9 (German)

- Dipasqua, Sandra & Calamari, Barbara (2004) Holy Cards. New York: Harry N. Abrams ISBN 0-8109-4338-7