History of the Khitans

| Khitan / Liao | ||||||||||||||

| 契丹 / 遼 / | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

Location of Khitan-Liao (1025) | ||||||||||||||

| Capital | Shangjing (918–1120) | |||||||||||||

| Languages | Khitan language | |||||||||||||

| Religion | ? | |||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | |||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||

| • | split from Kumo Xi | 388 | ||||||||||||

| • | set up the Liao dynasty | 907 | ||||||||||||

| • | defeated, some absorbed, some exiled | 1125 | ||||||||||||

| • | final defeat in a coup | 1211 | ||||||||||||

| Population | ||||||||||||||

| • | peak est. | 9,000,000 | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| 1. Other Khitan dynasties include Northern Liao and Qara Khitai (Western Liao). 2. The Liao dynasty had a different name, "Khitan", which was used in 916–947, 983–1066. | ||||||||||||||

The history of the Khitans dates back to the 4th century. The Khitan people dominated much of Mongolia and modern Manchuria (Northeast China) by the 10th century, under the Liao dynasty, and eventually collapsed by 1125 (or 1211).

Originally from Xianbei origins they were part of the Kumo Xi tribe until 388 when the Kumo Xi-Khitan tribal grouping was defeated by the newly established Northern Wei. This allowed the Khitan to resume their own tribe and entity which led to the beginning of Khitan written history.[1]

From the 5th to the 8th centuries the Khitan were dominated by the steppe powers to their West the Turks and then the Uyghurs. The Chinese also came from the south (Northern dynasties or Tang). In some cases they were under Korean domination (from the East, mainly Goguryeo) according to the balance of power at any given time. Under this triple domination the Khitan started to show growing power and independence. Their rise was slow compared to others because they were frequently crushed by neighbouring powers—each using the Khitan warriors when needed but ready to crush them when the Khitans became too powerful.

Enjoying the departure of the Uyghur people for the West and the collapse of the Tang dynasty in the early 10th century they established the Liao dynasty in 907. The Liao dynasty proved to be a significant power north of the Chinese plain as they were continuously moving south and West and gaining control over former Chinese and Turk-Uyghur's territories. They eventually fell to the Jin dynasty of the Jurchenin in 1125 who subordinated and absorbed the Khitans to their military benefit.[2]

Following the fall of the Liao Dynasty many Khitans moved further west and established the state of Qara Khitai. Their name survived in the Russian word for China (Китай, Kitay) as well as the archaic English (Cathay) Portuguese (Catai) and the Spanish (Catay) appellations of the name. They have been classified by Chinese historians as one of the Eastern proto-Mongolic ethnic groups – the Donghu (simplified Chinese: 东胡族; traditional Chinese: 東胡族; pinyin: Dōnghú zú).

Origins

References to the Khitan people in Chinese sources date back to the 4th century. Ancestors of the Khitan were the Yuwen clan of the Xianbei; an ethnic group situated in the area covered by the modern Liaoning province. After their regime was conquered by the Murong clan the remnants scattered in the modern-day Inner Mongolia and mixed there with the original Mongolic population.

Pre-Dynastic Khitans (388–907)

They had been identified as a distinct ethnic group since paying tribute to the Northern Wei dynasty in the mid-6th century.

During the time of the Chinese Tang dynasty the Khitan people were vassals to the suzerain Tang or Turks, depending on the balance of power between the two, or the suzerain Uyghurs when they replaced the Turks as the main steppe power. Once the Uyghurs left their home in the Mongolian Plateau in 842 enough of a power vacuum was left to give the Khitan the opportunity to cast off the bonds of subordinacy. The Khitan occupied the areas vacated by the Uyghurs bringing them under their control.

Khitan's military activities from 388 to 618

In the 5th century, the Khitan were under the Toba Wei influence.[3]

In the 6th century, the Khitan tribes were still a weak confederation after being heavily defeated in 553 by the Northern Qi who enslaved many Khitans and seized a large part of their livestock,[4] leading to harsh times for the Khitans. By that time the Khitan are still described as the lower level of nomadic civilization, their 'confederation' still being an anarchist system of isolated tribes, each tending his own sheep and horses and hunting on his private territory.[4] Some federal leaders were created after elections during a time of war after which it became a local power.[5]

When the Sui dynasty was established in 681 when the Khitan were living in a period of internal military turmoil. Their tribes were fighting each other[4] perhaps as a result of Sui Wendi strategy to increase tensions between nomads in order to create internal divisions. In 586 some Khitans tribes submitted to the Eastern Tujue (Turks) while others submitted to the Sui.[5]

Notable Khitan raids on the Chinese Empire were record as early as the 7th century. In 605 they staged a large scale raid southward invading Sui territories (Northern modern Shanxi, Hebei).[5] They were eventually crushed by a Sui general leading 20,000 Turkish cavalry.[6]

Military activities during the first half of the Tang dynasty (618–735)

The Li-Sun Rebellion (696–697)

Under Emperor Taizong of Tang (r. 626–649) the Khitans became vassals of Tang China.

Despite some occasional clashes the Khitans remained Chinese vassals until the 690s.[2] According to the "Loose rein policy" the Khitan area was under Tang control by the Governor-general of Yingzhou, Zhao Wenhui, assisted by local Khitan chieftains: namely the regional governor of Songmo Li Jinzhong and his brother-in-law, the Khitan chieftain and prefect of Guicheng Sun Wanrong.

Opposition rose because of the behaviour of Zhao Wenhui, who treated the local chieftains as his servants and humiliated them on many occasions, provoking resentment and because of a famine that struck the Khitan area in 696. According to the "loose rein policy" the Tang Governor-general was supposed to provide famine relief but when Zhao Wenhui failed to do so, adding injury to the insult done his local chieftains, the brothers-in-law launched a Khitan rebellion in the fifth month of 696.[2]

Li Jinzhong led the rebellion and quickly captured Yingzhou where he declared himself "Wushang Kehan" (無上可汗: "paramount khaghan"). Sun Wanrong assisted him as general successfully leading tens of thousands of troops southward.

The first significant Chinese response was to send an army with twenty-eight generals which was defeated by the Khitans in the Battle of Xiashi Gorge (near modern Lulong County of Hebei Province) in the eighth month of 696. Tang China was astonished by the announcement of the defeat and Empress Wu Zetian quickly issued decrees to launch a new offensive and encourage participation. Victory in battle remained with the Khitans until Li Jinzhong died of disease. The rising power of the Khitans also threatened the newly established Second Göktürk Empire (682–745) and the khagan Ashina Mochuo, who had supported their rebellion, now asked the Tang dynasty to be allowed to ally himself to Chinese efforts in exchange for: an imperial marriage for his daughter, adoption as the son of Empress Wu (diplomatic adoption), the return of Turks in Chinese territories (Hexi) and the restoration of Turkish overlordship of the Khitans.[2]

The second major Chinese offensive came in October 696, with Tang attacking from the south and the Türks from north; taking advantage of the recent death of Li Jingzhong. The Khitans were in a dangerous situation, suffering heavy losses, but Sun Wanrong took the lead and restored good order and motivation in the Khitan troops. They continuously stormed into Jizhou and Yingzhou shaking the whole region of Hebei (current north of Huanghe). This opposition was inconclusive. The powerful Wang Xiaojie, assisted by Su Honghui and some other Chinese generals, lead a third army of 170,000 troops to the area of the Xiashi Gorge where they were also crushed by the Khitans. Wang Xiaojie was killed while Su Honghui fled and in their wake the Khitans were allowed to capture the frontier garrison of Youzhou, south of Yingzhou.[2]

In a fourth campaign during May 697, Empress Wu sent Lou Shide and Shatuo Zhongyi north with 200,000 troops to stop Sun Wanrong's southern advance. Despite the Khitan history of victory the Turks refused the proposed Khitan-Turk alliance to launch a massive attack on Xincheng while (Kumo) Xi betrayed the Khitans to China. The Khitan populace was now facing devastating Turkish raids in the north with the Khitan army facing 200,000 Chinese and Xi troops in the south. In this critical situation the Khitan command fractured ending in the assassination of Sun Wanrong by one of his own subordinates. The Khitan troops were without a clear leader and collapsed with the remaining Khitans transferring their allegiance to the Turks (as did the Xi) as Mochou Khaghan and the Empress Wu Zetian had planned early in 696. And a new Khitan chieftain was proclaimed: Li Shihuo (697–717, [李]失活).[2]

Consequently, the Khitan, together with the Xi and both under Turkish leadership, remained aggressive towards the Chinese with the Tang launching several punitive campaigns against them from 700 to 714.[2]

The Li-Sun rebellion and the Turks

The Turks played a major role in crushing a rebellion in military actions and in a strategic role as well. The Turks were to submit to China in 630 after their first Turkish Empire was crushed. In 679 during a period of Chinese internal political turmoil they revolted. They were defeated by Tang troops in 681 in a Pyrrhic victory, also, the remaining Eastern Turks reunited under Ashina Guduolu (died 691) who was able to proclaim the rebirth of the Turkish empire without Tang's reaction.[7]

When Li-Sun died his brother Mochuo replaced him and engaged the Turks in an aggressive policy of "plunder to strengthen" as the best way to revitalize his Empire. The Turks plundered all their neighbour, the Khitan and Chinese included, but encouraged the Khitans to rebel against Tang rule. Almost as soon as the Khitan rebelled and were successful the Turks proposed an alliance with China. The Turks, engaged in a war against China, were just asking the Khitans for a diversion in the east allowing them to be more free on their front. When the Khitans unexpectedly appeared to be successful they both were surprised and afraid at seeing a new power born on their East. Seeing the Khitans fighting hard against the Chinese seemed the perfect occasion to take advantage of both the busy Khitan and the downtrodden Tang. By attacking Khitan on their rear the Turks provided an inestimable help to Tang which also worked for themselves by crushing that eastern rising power.[7]

While the fourth Chinese campaign was still not launched, and despite previous propositions of alliance, the Turks attacked the Chinese territories to show clearly they were strong in the third month of 697. Along with the final victory they freed some Turkish prisoners held in six Chinese northern border prefectures since 670–674, gained the submission of both the Khitan and the Xi, plundered a large amount of seed-grain, silk, farming implements and iron as well as winning noble titles for the Mochou khaghan (such as General, Khaghan and other noble ranks) and the asked for imperial marriage.[7]

The Ketuyu rebellion (720–734)

In the 710s the Khitan military chief Ketuyu (可突于) was so valiant and beloved by Khitan's commoners that the Khitan King Suogu (李娑固 Li Suogu, r. 718–720) became both jealous of him and in fear of a take-over. Accordingly, he plotted to assassinate Ketuyu. As is often the case the plot was disclosed and Ketuyu's troops attacked the King who fled to Yingzhou to get Chinese support.[8]

Xu Qinzhan (許欽?[9]), the Chinese Governor-General of Yingzhou, immediately called for a punitive military campaign ordering General Xue Tai assisted by 500 valiant soldier,[10] Xi troops, and Suogu troops to go northwards. The Chinese-loyalist army was crushed and both Suogu (Khitan King) and Li Dapu (Xi King) were killed while Xue Tai was captured by Ketuyu. In hope of resuming good relations with the Chinese Tai was not executed and an envoy was sent to humbly apologize while Ketuyu enthroned Suogu's cousin Yuyu (李鬱于, 720-722/724).[8]

Peaceful relations were restored and when Ketuyu made a second coup to face the new king Tuyu(or Yuyu?) suspicions, the Tang court peacefully confirmed the newly enthroned king Shaogu (李邵固 Li Shaogu, 725–730) who on his side displayed respect for Tang's wishes of appeasement.[8]

In 730 Ketuyu went to present tributes to Chang'an but was mistreated by chancellor Li Yuanhong. Back in the Khitan territories Ketuyu assassinated the pro-Tang Shaogu in the fifth month of 730 and switched the allegiance of his subjects, and of the Xi tribes, from Tang to the Türks sending a clear message to Tang. Ketuyu then attacked Pinglu (part of Yingzhou) where a defensive army of Tang's was stationed. The Chang'an officials were panicked by the vision of a new Khitan rebellion and ordered Prince of Zhong Jun, as commander in chief assisted by 18 generals, to go north with warriors recruited from as far as Guannei, Hedong, Henan and Hebei to crush this Khitan-Xi rebellion.[8]

In the third month of 732 the Khitan-Xi troops were defeated by the Prince of Xin'an and Ketuyu had to flee while Li Shi Suogao, the Xi king, betrayed him submitting to Tang with his 5,000 subjects[11] getting the titles of the Prince of Guiyi (allegiance and righteousness) and prefect of Guiyi Zhou with the Xi allowed to settle in Youzhou under Chinese protection.

A second major campaign came in the fourth month of 733 when Guo Yingjie was ordered to lead 10,000 troops, assisted by Xi warriors, to crush Khitan. Ketuyu came first with Turkish support putting the Chinese-Xi troops in difficulty forcing the Xi to flee to save themselves. Predictably Guo Yingjie and his men, left alone to face the Khitan-Turkish troops, lost with heavy casualties. Guo and most of his men were killed on the battlefield. One year later the Khitan were defeated by Zhang Shougui, regional commander of Youzhou in the second month of 734.[8]

Ketuyu, seeing the Khitan forces exhausted by repetitive Tang campaigns, pretended to surrender in the twelfth month of 734 and was murdered, together with his puppet King Qulie (李屈列 Li Qulie 730–734), by his subordinate Li Guozhe (李過折). Li Guozhe was soon himself assassinated in favor of a Ketuyu clan restoration.

Origins of the Ketuyu Rebellion

While traditional scholars explain this Ketuyu Rebellion as a typically barbarian reaction modern historians are more cautious. Both the Chinese Liao expert Shu Fen and the Japanese Matsui Hitoshi are inclined to think that Chinese lenient policy encouraged Ketuyu's arrogance. In contrast, Xu Elian-Qian supports the theory that Chinese interferences in Khitan internal changes caused the aggression to Ketuyu's reactions. That may be true for the conflict of 720 and the aggressive Chinese behaviour. But this opinion does not explain the Chinese appeasement policy in 725 where the Chinese let Ketuyu kill the Khitan king and enthrone a new one. When Ketuyu was personally mistreated, in Chang'an in 730, this resentment led him to choose the larger of consequence of diplomatic opposition by turning his submission to the Turks. This was predictably understood by Chang'an as a first magnitude treason which could not be tolerated and lead to the ensuing five years of war to recapture them. Shu and Matsui do not see this Chinese reaction as an aggressive interference but rather as a predictable interference caused by Ketuyu's arrogant reaction to the recent lenient policy.[8]

Xu explains that the Khitans were at a turning point. The Dahe family collapsing as an after-shock of the Li-Sun Rebellion while the Yaonian family was growing by organizing a new confederation of alliances. Accordingly, this period was rich in turmoil. The opposition may have come from the respective perceived definition of the Loose rein agreement. In times of weakness in the central power, such as in the 680's, this loose rein policy meant largely independence for the subordinate population who chose their own chief etc. In times of strong central power, as under Tang Xuanzong (r. 712–756), the central Chinese power was inclined to impose pro-Chinese choices, including in choice of Kings and major chiefs, despite the previous loose rein agreement. Also in prosperous times such as Xuanzong's reign, and his courage in facing the 720's coup, Tang officials immediately sent an army to support the dethroned pro-Tang king clearly interfering in Khitan internal affairs.[8]

The 730–734 war seems to have been the consequence of both Chinese revitalized foreign policy, Khitan internal turmoil and associated oppression of Ketuyu and the miscalculations made by him.

An Lushan era (750s)

Rise of An Lushan and Chinese-on-Khitan hostilities

By the 730s regional commanders already have largely autonomy of initiative to face neighbouring threats and accordingly boundary wars and rebellions are understood by many scholars as the full responsibility of local general commanders.

In the third month of 736 Zhang Shougui, the general commander of Youzhou, sent his protected An Lushan, an officer of the Pinglu Army (平盧軍) based in modern Chaoyang who was said to know 6 languages of Chinese, to attack Khitan and the Xi rebels but An Lushan made an overtly audacious attack which cost him almost all of his troops. He escaped the usual execution for such disobedience cases in part because of Zhangs affection for him and in part thanks to Emperor Xuanzong who, overviewing death penalty cases, believed that his audacious and mid-barbarian character should not pay by death.[12]

Youzhou soon became the Bingmashi (兵馬使) of the Pinglu Army in the seventh month of 741. He carefully cultivated relationships with other officials and generals to earn praises and bribed Imperial messengers to include him in their reports. As the consequence of this systematic bribery he was promoted to commandant at Yingzhou (Ying prefecture) and Jiedushi (military governor) of the Pinglu army[13] in 742 to face and defeat the northern threat from Khitans, Xi, Bohai and Heishui Mohe.[12][14] He was made military governor of Fanyang Circuit (范陽, headquartered in modern Beijing) in 744 plundering Khitan and Xi villages to display his military abilities. This continuous harassment of Khitan is understood by some scholars as provocation to the Khitan aggressiveness and the threat aimed to get more troops from Chang'an for his future rebellion as well as the reason for the 745 Khitan-Xi rebellion.[14]

As commander of the northeastern frontier in 744–755 An Lushan organised military operations against the Khitan-Xi nomads. His motivation was to curry favour with the Tang court and probably also to obtain more troops. He needed these for his subsequent campaigns to defeat what he saw as the enormous threat presented by the northeastern "babarians" amongst who the Khitan were the most significant. He may also have been motivated by thoughts of preparing for his future rebellion of 755–763.

745s Khitan rebellion

In the third month of 745 several Tang princesses were married to Khitan's leaders in a sign of appeassment. But for some reason[15] the Khitans soon turned into an open rebellion against Tang in the ninth month of 745 killing the princesses and starting military operations. Huge previous pressures from An Lushan combined with the Chang'an courts praise for him may have been seen Khitan as presenting an impasse against which they eventually revolted.

The Khitans were quickly defeated by An Lushan's toops by punitive expeditions and traps. Sources report that Banquets for a peace declaration were set up by An Lushan and offered to Khitan and Xi who,happy to get both peace and free provisions, rushed to the buffet and drunk heavily. It turned out that the food and wine were poisoned by narcotics. An Lushan then led his warriors to kill all of those who were sleeping on the ground or drunk enough to be easy to kill and the Chiefs' heads were sent to the Tang court for display. Sources have said that each of such Banquets ended with the death of thousands of warriors. This claim is difficult to believe: can Khitan have been that naive to let An Lushan kill thousands of them, several times, in the same kind of "free food traps". The difficulty is that Chinese sources seem biased against An Lushan depicting him by this story as a terrible untrustable enemy. The final result was that Khitan's 745 rebellion was crushed.

751–752s wars to 755s An Shi rebellion

In 751–752, following An Lushan's provocations and harassment, the Khitans moved south to attack the Chinese Tang Empire. Accordinglys Khitan were soon subject to a Chinese campaign in the eighth month of 751: An Lushan assisted by 2,000 Xi guides leading 60,000 Chinese troops into Khitan territories. When the fighting started the Xi suddenly turned their support to Khitan and the Khitan-Xi army then quickly pushed against the Tang armies who were hampered by rains. The Khitan-Xi army killed almost all the enemy soldiers while An Lushan escaped to Shizhou with just twenty cavalrymen. The defending general Su Dingfang, a Tang general, was eventually able to stop the Khitan pursuit troops which retreated. They had their battlefield victory, although not An Lushan's head, and so they laid siege to the city which only Shi Siming (one An Lushan's general) was able to end. One of his generals was killed in action and, after retreating, he blamed and executed the other two for the defeat.

In 752, to punish this audacity and insult, a 200,000 strong army including both Chinese and barbarian infantry and cavalry went northwards to meet the Khitan. But while An Lushan requested that the ethnically Tujue general Li Xianzhong (李獻忠) accompany him Li feared An and, when compelled to, rebelled putting a halt to An's campaign.[16] After three years in the month fourth of 755 An announced his victory about which historical records are not very clear. By this time An Lushan was already engaged in an opposition to the Yang clan located in Chang'an which turned around his system of alliances. Put into an impasse he rose into rebellion and had to walk southwards to quickly beat the unprotected heartland of the Tang territories. In this movement he looked for assistance from the northern nomads: Tujue, Uighurs, Khitan, Xi and Shiwei. All, to some extent, assisted his troops and his rebellion, Khitan principally by his previously taken prisoners'. But the Khitan were exhausted and took little part in these campaigns.

- Background reasons of these oppositions

The continuous agitation of Khitans on the northeast of the Empire, maintained by An Lushan actions, provided An Lushan more and more support troops from Chang'an for his own power and ambitions growing to 160,000–200,000 men. This was caused by several factors:

- An Lushan seemed to be a clever military official especially skilled to set up good relationships with his superiors, whatever by systematic brides (as say sources) or by his possible real abilities;

- An Lushan was skilled to both: up Khitan's aggressivity, enlarge the threat in his rapports, and trap/crush them, getting large praises

- the time (740s) was an apogee of prosperity, the treasury was full, the Chinese Empire was at a maximum of extension, Xuanzong and Chang'an officials sur-estimated their own power and displayed growing mark of lazy behaviour and management: waste of financial resources, lack of troops in the Central area;

- in Chang'an, the high chancellor Li Linfu, facing to the rise of the Yang clan in Chang'an, wanted both to resist the Khitans' pressure and counterbalance the growing influence of the Yang clan in Chang'an affairs.

Accordingly, An Lushan's power strengthened with associated pressure on the Khitan.

The turning point came when An became worried about the post of Xuanzong-Li Linfu (An Lushan add "get their favor", but at the cost of relations with other officials). Noticing that the heart of the empire was without defenses An considered to plan a rebellion. He selected a dozen able generals and some 8,000 soldiers from amongst the surrendered Khitan, Xi, and Tongluo (同羅) tribesmen organizing them into an elite corps known as the Yeluohe (曵落河, "the brave").[16]

When Li Linfu died and Yang Guozhong, a Yang clan member, replaced him as high chancellor An Lushan rose in rebellion with his armies and attacked the central power with Khitan, Xi and Turkish supporters.

2nd half of the Tang dynasty (763–907)

- Middle of Tang's dynasty

The Khitan were concentrating themselves on their own development and were relatively peaceful.

- Uighurs domination and Khitans state

When the Turks where overthrown by the Uighurs in 745 the war-loving power of the Turks was replaced by the commerce-loving Uighurs. The control that the Uighurs had on the Khitans were of a different kind. Uighurs were focusing on economic exchanges, were the protectors of the diplomatic stability and left large political and internal freedom to their vassals. The Khitans used this to keep a peaceful environment helping to strengthen all their demographic, economic and structural force.

For their demographic the main point was the choice to avoid foreign conflicts. The new "Steppe Lords" were relatively peaceful while the Tang dynasty was later greatly weakened by the An-Shi rebellion of 755–763 providing a new intra-China situation with a weak center and with provincial generals pacification and strengthening of their respective provinces. In this context the Khitans and their close-relatives the Xi had opposite strategies. Kumo Xi kept a relatively aggressive foreign policy slowly exhausting their forces. The Khitans chose to stay as a calm self-defensive power enjoying most of the Manchurian plain and working to improve their daily situation. While previous centuries had seen successive Turko-Chinese provocations or recall to obeisance, and the following wars had prevented Khitan gaining any notable expansion, the 8th-century situation eventually allowed one. This demographic growth would strongly support the other qualitative changes.

Pre-dynastic Khitan's allegiances and reasons

- pre-388 : Kumo Xi – submitted to the Turks. Part of the Kumo Xi-Khitan tribal complex[17]

- 388-?:[17] Later (383–409) & Northern Yan (409–436) – a result of the 388 Kumo Xi defeat facing the Northern Wei

- 479-?:[17] Northern Wei – to avoid a Rouran-Goguryean invasion

- 560's(?)-?:[17] some tribes submitted to Goguryeo to avoid Northern Qi and Eastern Turk threats;

- 648–696:[18] Tang dynasty– because of recent Tang expansion and following the Turkish collapse.

- 696–697 : independent (Li-Sun Rebellion) and in war on all sides, encouraged by Tujue and caused by Chinese official mistreatment a famine.

- 697-72X : Tang dynasty+ Tujue, since the 697 defeat.

- 730–734:[8] Turks – Ketuyu Rebellion caused by Tang interventionism and Tang's Chancellors mistreatment.

- 734-? : Tang Dynasty – because of recent defeat.

- To complete

Liao dynasty, The Golden Age (907–1125)

The Liao dynasty was founded in 907 when Abaoji, posthumously known as Emperor Taizu, was named the leader of the Khitan nation. Even though the Great Liao dynasty was not declared until the 947 it is generally said to have begun with the elevation of Abaoji to emperor.

Though Abaoji died in 926 the dynasty would last nearly two more centuries. Five cities were designated as capitals during that dynasty. In addition to the supreme capital in the heartland of Khitan territory there were four regional capitals. One of which was Beijing which became a capital for the first time in its history. It was not the principle capital of the dynasty but rather was designated as the southern capital after the Khitan acquired the contentious Sixteen Prefectures in 935.

Abaoji introduced a number of innovations – some more successful than others. He divided the empire into two parts: one was governed based on nomadic models while the sedentary population was governed largely in accordance with Chinese techniques. Less successful was the attempted introduction of primogeniture in succession to the throne. Although he desired his eldest son to be heir he did not succeed Abaoji.

Abaoji was "afraid that their use of Chinese advisers and administrative techniques would blur their own ethnic identity, the Khitan made a conscious effort to retain their own tribal rites, food, and clothing and refused to use the Chinese language, devising a writing system for their own language instead."[19] The first of these two scripts was created in 920. The second, based on alphabetic principles, was created five years later.

Post Liao dynasty history

The Khitans were absorbed by the Jurchens and widely used in the following years of war to conquer the northern Song territories. In contrast a number of the nobles of the Liao dynasty escaped the area towards the Western Regions establishing the short-lived Qara Khitai or Western Liao dynasty. They were in turn absorbed by the local Turkic and Iranian populations and left no influence of themselves. As the Khitan language is still almost completely illegible it is difficult to create a detailed history of their movements. The Khitans were mainly employed by the Mongols in military and civil services after they conquered most of Eurasia. Daur people and some Baarin people are direct descendants of the Khitans.[20]

Fleeing from the Mongols, in 1216 the Khitans invaded Goryeo and defeated the Korean armies multiple times, even reaching the gates of the capital and raiding deep into the south, but were defeated by Korean General Kim Chwi-ryeo who pushed them back north to Pyongan,[21][22] where the remaining Khitans were finished off by allied Mongol-Goryeo forces in 1219.[23][24] These Khitans are possibly the origin of the Baekjeong.

Historical atlas

- Territories of the Khitans from 400 to 1050

-

400

-

500

-

600

-

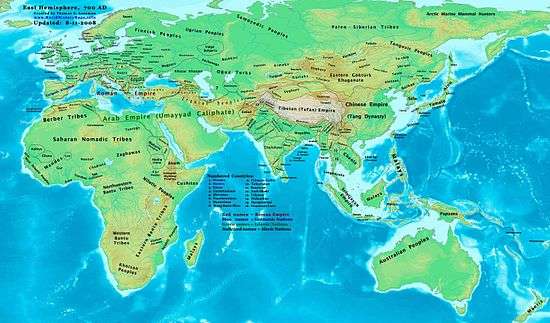

700

-

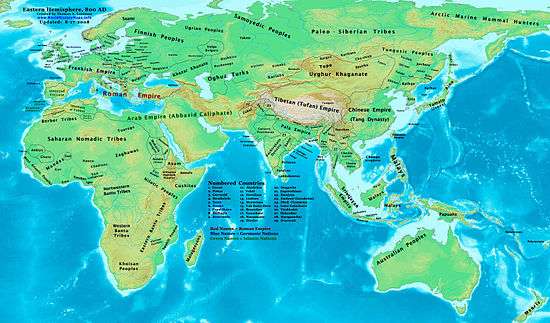

800

-

900

-

1025

-

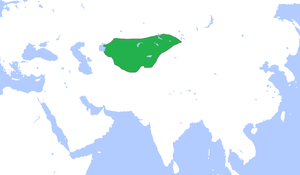

Qara Khitai circa 1200

-

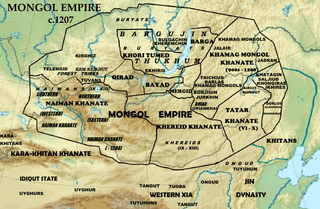

Mongol Empire circa 1207, showing the locations of the Qara Khitai and Khitans

See also

- Sub-studies

- Pre-dynastic Khitan (388–907), before the Liao empire (include in this article)

- Liao dynasty (907–1125), the Khitan Empire.

- Qara Khitai (1125–1211), the kingdom set up by escaped Khitans

- Ethnic and states context

- Origines: Donghu → Xiongnu → Xianbei → Kumo Xi → Khitan

- Steppes (west) : Rouran (4th to 6th), Turkish Empire (5th to 8th) and Uyghur Empire (8th and 9th centuries), Kumo Xi

- China (south) : Northern dynasties (5th and 6th, especially Northern Wei), Tang (7th to 10th centuries), Song dynasty

- From East: Goguryeo, Jurchen, Goryeo (Goryeo-Khitan Wars)

- From North: Rouran, Didouyu, Mohe

See also Ethnic groups in Chinese history

- Major Khitan characters

- Li Jinzhong (died 696) and Sun Wanrong (died 697)

- Ketuyu (died 734)

- Abaoji (Taizu)

See also List of the Khitan rulers

- Other

Notes

- ↑ Xu Elina-Qian, 258

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Xu Elina-Qian, p.241 and p.237

- ↑ To expand this section, please use Xu Elina-Qian, p.155–172, and CHOC-6, pp. 44–50

- 1 2 3 CHOC 6, p46

- 1 2 3 CHOC-6, p47

- ↑ CIHofC, p.111

- 1 2 3 Xu Elina-Qian, p.243–245

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Xu Elina-Qian, p.245–248

- ↑ Xu Elina-Qian, p.293a

- ↑ XTS 43. 1119 and 37. 930. Xu Elena-Qian also talk about « a tens of thousand strong army was being mobilized from Guanzhong to reinforce this operation » (37. 930.). But did them were on the battlefield when Li Dapu (Xi King) and Li Suogu (Khitan dethroned King) were killed ?

- ↑ Note: what is this ? it was just 5,000 Xi at this time ?

- 1 2 Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 214.

- ↑ The Pinglu Army under his leadership being promote to be a military circuit, is Bingmashi rank was upgraded to Jiedushi rank (military governor).

- 1 2 Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 215

- ↑ what?

- 1 2 Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 216

- 1 2 3 4 Xu Elina-Qian, p.264

- ↑ Xu Elina-Qian, p.247

- ↑ 2006 Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- ↑ Inner Mongolian "Odon" television

- ↑ "Kim Chwi-ryeo". Encyclopedia of Korean Culture. Academy of Korean Studies. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- ↑ Goryeosa: Volume 103. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- ↑ Patricia Ebrey; Anne Walthall (1 January 2013). Pre-Modern East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History, Volume I: To 1800. Cengage Learning. pp. 177–. ISBN 1-133-60651-2.

- ↑ Lee, Ki-Baik (1984). A New History of Korea. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 148. ISBN 067461576X.

References

- Pre-dynastic Khitan

- Xu Elina-Qian, Historical Development of the Pre-Dynastic Khitan, University of Helsinki, 2005. 273 pages. (for pre-907)

- MATSUI, Hitoshi 松井等 (Japan). "Qidan boxing shi 契丹勃興史 (History of the rise of the Khitan)". Mamden chiri-rekishi kenkyu hokoku 1 (1915).

Translated into Chinese by Liu, Fengzhu 劉鳳翥. In Minzu Shi Yiwen Ji 民族史譯文集 (A Collection of Translated Papers on Ethnic Histories) 10 (1981). Repr. in: Sun, Jinji et al. 1988 (vol. 1), pp. 93–141 - Chen, Shu 陳述. Qidan Shi Lunzheng Gao 契丹史論證稿 (A Study on the History of the Khitan). Beijing: Zhongyang Yanjiu Yuan Shixue Yanjiu Suo 中央研究院史學研究所, 1948.

- Chen, Shu 陳述. Qidan Shehui Jingji Shi Gao 契丹社會經濟史稿 (A Study on the Khitan's Social Economical History). Shanghai: Sanlian Chuban She 三聯出版社, 1963.

- Feng, Jiasheng 1933.

- Marsone, Pierre, La Steppe et l’Empire : la formation de la dynastie Khitan (Liao) Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 2011, 322 p. https://www.academia.edu/4954295/La_Steppe_et_l_Empire_la_formation_de_la_dynastie_Khitan_Liao_

- Liao dynasty

- Shu, Fen (舒焚), Liaoshi Gao 遼史稿 (An History of the Liao). Wuhan: Hubei Renmin Chuban She 湖北人民出版社, 1984

- WITTFOGEL, Karl & FENG, Chia-sheng. History of Chinese Society: Liao (907–1125). Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1949.

- Post-dynastic / Qara Khitai

- Biran, Michal. The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History: Between China and the Islamic World, ISBN 0-521-84226-3

- Useful official dynastic histories

- Wei Shu 魏史 (Dynastic History of the Northern Wei Dynasty): Wei, Shou 魏收 et al. eds. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju 中华书局, 1973.

- Xin Wudai Shi (XWDS) 新五代史 (New Dynastic History of the Five Dynasties): Ouyang, Xiu 歐陽修 et al. eds. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju 中华书局, 1974.

- Sui Shu (SS) 隋書 (Dynastic History of the Sui Dynasty): Wei Zheng 魏徵 et al. eds. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju 中华书局, 1973.

- Jiu Tangshu (JTS) 舊唐書 (Old Dynastic History of Tang Dynasty): Liu, Xu 劉昫 et al. eds. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju 中华书局, 1975.

- Xin Tangshu (XTS) 新唐書 (New Dynastic History of the Tang Dynasty): Ouyang, Xiu 歐陽修 et al. eds. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju 中华书局, 1975

- Liao Shi (LS) 遼史 (Dynastic History of the Khitan Liao Dynasty): Tuotuo 脱脱 et al. eds. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju 中华书局, 1974

- Song Shi 宋史 (History of Song): Tuotuo 脫脫 et al. eds. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju 中华书局, 1974

- Zizhi Tongjian (ZZTJ) 資治通鑒 (Comprehensive Mirror to Aid in Government): Sima, Guang 司馬光 ed. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju 中华书局, 1956

- Other

- Mote, F.W. (1999). Imperial China: 900-1800. Harvard University Press. pp. 31–71. ISBN 0-674-01212-7.

- EBREY, Patricia Buckley (1996). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-66991-X.

- TWITCHETT, Denis (1994). The Cambridge History of China: Alien Regimes and Border States, 907–1368. Cambridge University Press. p. 816. ISBN 0-521-24331-9. (pp. 43–153)

- Khitans

- Khitans on scholar.google.com