History of the Armenian Americans in Los Angeles

| Part of a series on |

| Ethnicity in Los Angeles |

|---|

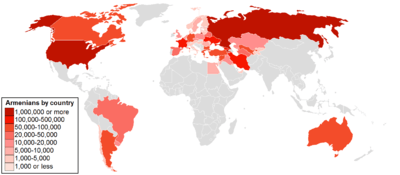

The Los Angeles metropolitan area has a significant Armenian American population. As of 1990 this single area holds the largest population of Armenians in the world outside of Armenia,[1] or Iran.

Anny P. Bakalian, author of Armenian-Americans: From Being to Feeling Armenian, wrote that "Los Angeles has become a sort of Mecca for traditional Armenianness."[2] Since 1965 and as of 1993, the majority of immigration of ethnic Armenians from Iran or the former Soviet Union have gone to the Los Angeles area.[2]

History

The first Armenian families began to settle in the Los Angeles area starting in the late 19th century. Aram Yeretzian, a social worker and Protestant Christian minister who wrote a 1923 University of Southern California thesis on the Armenians of Los Angeles, stated that the first Armenian in Los Angeles arrived in around 1900. According to Yeretzian, the first Armenian was a student who left the East Coast due to health concerns. Yeretzian stated that the second Armenian was a vendor of Oriental rugs.[3] However, another states that In 1889 brothers John and Moses Pashgian opened their oriental rug business in Pasadena- which would make them the first.

The first significant wave of Armenian immigration occurred from western Armenia, due to the Armenian Genocide during the violent disruption and break-up of the Ottoman Empire.[4] Most of the early Armenian settlers to Los Angeles were from Western Armenia- a territory located in modern-day eastern Turkey.[5] Circa 1923 there were an estimated 2,500 to 3,000 Armenians in the city.[3] By the mid-1920s more Armenians were settling in the Pasadena area. In 1924 the Varoujan Club was founded by 20 young Armenians to organize Armenian cultural and social events. During this period, the Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU) and the Compatriotic Reconstruction Union of Hadjin were founded. By 1933 there were 120 Armenian families in Pasadena. Nearly all of these immigrants were from the Ottoman Empire; very few were from the Russian Empire. The Pasadena Armenians settled in the area of Allen Avenue and Washington Boulevard, near the Church of the Nazarene, which was used by the Protestant Armenians.[6]

Another wave of immigration to Los Angeles occurred in the 1940s. Most Armenians then settled in Little Armenia in Hollywood.[7]

Due to the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which eased restrictions against newer immigrant groups, another wave of Armenian immigration to Los Angeles began. The Lebanese Civil War beginning in 1975 resulted in Lebanese Armenians immigrating here.[5] Other political conflicts around the same time were catalysts for Iranian Armenians and Egyptian Armenians to settle in Los Angeles as well. Armenians from Fresno and the East Coast also moved to Los Angeles because of the large community there.[4]

Approximately 9,500 Armenians came to the United States in 1979 and 1980, and most settled in Hollywood. In August 1987, as part of glasnost, the Soviet Union began approving for exit visas for Armenians wishing to emigrate to the United States to reunite with relatives. As a result, from October 1987 through March 1988, 2,000 Armenians arrived in Los Angeles County. That March, county officials were expecting an additional 8,000 Armenians to arrive. The county officials stated that the expected immigration of 10,000 Armenians from the Soviet Union was the single largest arrival of an ethnic group after the late 1970s Vietnamese immigration.[8] Some Los Angeles-area Armenian leaders believed that increased settlement in the United States would dilute the Armenian presence in the Soviet Union and area around Armenia, and therefore felt ambivalence.[8]

In 1988 up to 3,000 Iranian Armenians were scheduled to arrive in the Los Angeles area.[8] From 1987 to 1989, 90% of Armenians leaving the Soviet Union settled in Los Angeles.[9] By the 1990s political conflict in the former Soviet Union caused more Armenians in that area to move to Los Angeles.[4]

In 2010 Kobe Bryant of the Los Angeles Lakers signed a two-year endorsement with Turkish Airlines. Because the company is owned by the Turkish government, which the Armenians hold responsible for the unacknowledged 1915 genocide, Armenians in the Los Angeles area and US protested, asking him to give up the contract.[10]

By 2014 the Los Angeles area had received additional Armenian refugees from Egypt and Syria.[11] The ongoing Syrian civil war is responsible for the recent wave in refugee arrival.

Demographics

The Armenian population is subdivided according to their countries of birth, where groups had developed distinctly different cultures. In addition to those born in Armenia, these include those born in the United States, Iranian Armenians, Lebanese Armenians, and Turkish Armenians,[12] as well as those from elsewhere in the former Soviet Union and the Middle East.[13]

1920s

Aram Yeretzian's 1923 University of Southern California study found that there were around 2,500 to 3,000 Armenians in the city of Los Angeles. 12 Armenian men had married women from several backgrounds including American and Spanish, and three Armenian women had married American men. At the time the majority of Armenians were Turkish Armenians while some came from what was Russia at the time.[3] The main push factor for Armenians was the Armenian Genocide—however, most Armenians ended up dispersed in countries such as Iran, Syria, Lebanon and Egypt.

1970s

With turbulent situations in Lebanon, Egypt and Iran during the 1970s, many Armenians came to the U.S. via family reunification channels.[14]

1980s

By the 1980 U.S. Census, there were 52,400 Armenians in Los Angeles.[12] Citing a 1988 work by Lieberson and Waters, Bakalian wrote, "It should be noted that scholars find that these statistics from the 1980 census underestimate the actual number of Armenians in Los Angeles, and elsewhere in the U.S. for that matter".[15]

Of these Armenians, foreign-born made up more than twice the number of native-born: 14,700 were born in the United States and 37,700 were born outside of the United States. Of those born in the U.S., 10,200 were born in California and 4,500 were born elsewhere. Of those born outside of the U.S., 7,700 came from Iran, 7,500 from the former Soviet Union, 6,000 from Lebanon, 5,100 from Turkey, 6,200 from elsewhere in the Middle East, and 5,200 from other countries.[13]

Immigration had been heavy in the 1970s. As of 1980 about 66% of Armenian immigrants overall, 70% of immigrants from the former Soviet Union, Iran, and Lebanon, and 60% of Armenians from Turkey, had arrived between 1975 and 1980.[5]

As of 1980 the median age of U.S.-born Armenians in Los Angeles was 25. The median age for Turkish Armenians was 64; they had resided in the U.S. the longest. The median ages for other Armenians born outside of the U.S. ranged from 26 to 36.[5]

One major push factor for Armenians in the 1980s was the 1988 Armenian earthquake which left many buildings destroyed in Yerevan. Soviet policy at the time allowed for many of the refugees to reunite with family abroad.[16]

1990s

As of the 1990 U.S. Census, there were 115,000 Armenians in the Los Angeles region, making up 37% of the total number of Armenians in the country.[1] The dissolution of the Soviet Union allowed many Armenians to move abroad.

Geography

The Burbank/Glendale, East Hollywood, Montebello, and Pasadena areas are the primary settlement points of Armenians, according to the 1980 U.S. Census; as of that census the Armenians in the areas together made up 90% of the Armenians in Los Angeles County.[5] As of 1991 the established Armenian communities in the area included Encino and Hollywood in Los Angeles as well as the cities of Montebello and Pasadena. The Burbank/Glendale settlement is newer.[17]

The Little Armenia in Hollywood historically had Armenians from Armenia. In 1980 the Armenians in East Hollywood made up 56% of the Armenians in Los Angeles County.[5] In 1988, Mark Arax and Esther Schrader wrote that Hollywood "has become something of a port of entry for the Soviet refugees."[8] In 1989 Vered Amit Talai wrote that "the Soviet Armenian emigrants form a very visible community in Hollywood".[18] In 1988 the Los Angeles-area chairperson of the Hunchak Party, Harry Diramarian, stated "'Going to Hollywood, going to Hollywood.' You hear it all the time on the streets of Yerevan."[8] In 1988, Little Armenia, had many Armenian residents operating bakeries and living in apartments above the businesses.[8] Zankou Chicken had opened in Hollywood in 1984.[19] In 1989 Talai wrote that Armenians in Hollywood had a negative effect on the Armenian reputation in California because they were "visible" and "indigent" but that the indigent status is "unusual" relative to the overall Armenian diaspora.[18]

On October 6, 2000, the community in East Hollywood was named Little Armenia by the Los Angeles City Council. The city council noted that "the area contains a high concentration of Armenian businesses and residents and social and cultural institutions including schools, churches, social and athletic organizations."[20]

By 1988 many Armenians were moving from Hollywood to suburban Glendale, Burbank, and other areas.[8] By that time, some immigrants settled directly in Glendale and Burbank.[8] Historically many of the Glendale Armenians were from Iran.[21]

In the 1980 U.S. Census the Armenians in Glendale were 25% of the Armenians in Los Angeles County.[5] In the Glendale Unified School District, by 1988 Armenians along with students from the Middle East had become the largest ethnic group in the public schools, having a larger number than the Latinos. Alice Petrossian, the GUSD director of intercultural education, stated that Burbank lies within the middle of other Armenian communities, so it attracted more Armenians.[17] Levon Marashlian, an Armenian history teacher at Glendale Community College, stated that Glendale's Armenian population became larger than Hollywood's by the early 1990s.[7] As the 2000 U.S. Census, 30% of the residents of Glendale were Armenian.[22] By 2000 Glendale had the largest Armenian population outside of Yerevan.[7]

Historically many U.S.-born Armenians settled Montebello and Pasadena. In 1980, the Armenians in Pasadena were 9% of the county's total number of Armenians.[5] By 1989, the makeup of the Armenian community in Pasadena had changed: of the Armenians in Pasadena, 33% were born in Lebanon, 17% were U.S.-born, 16% were born in Armenia, 12% were born in Syria, and the remainder were born in other places. The city government had gathered the data through a special census.[23]

Economy

As of 1996, the self-employment rate of Armenian managers and professionals in Los Angeles is over 66%.[24]

As of 1980, of the total number Armenian men 16 and older, 25% worked as executives and professionals.[25] Of the same total, 44% were craftsmen and operators. As of that year, 32% of U.S.-born Armenian and Iranian-born Armenian men worked as executives and professionals, and about 33% of the same group worked as craftsmen and operators.[26] As of the same year, 15% of Armenian men from Armenia worked as executives and professionals,[27] and about 66% of the same group worked as craftsmen and operators.[26]

The 1980 self-employment rate of Armenians in total was 18%. Of the Turkish Armenians the rate was 32%. The other Armenian groups had self-employment rates close to 18%. Armenia-born Armenians had an 11% self-employment rate. Der-Martirosian, Sabagh, and Bozorgmehr wrote that the Armenia-born Armenians were less likely to start their own businesses compared to other groups because "the tradition of entrepreneurship may not have been as strong in the Soviet socialist economy as it remained in Middle Eastern market economies."[26] In addition, this group had arrived with no or very little capital and the members were not permitted to take money out of the former Soviet Union. The 1980 percentage of general employment of the general Los Angeles population was 9%.[26]

Compared to other Iranian groups, Iranian Armenians had a higher likelihood of economic ties with one another. Most customers and employees of Iranian Armenians who had self-employment were not Armenian and not Iranian, while most business partners of self-employed Iranian Armenians were fellow Iranian Armenians. Der-Martirosian, Sabagh, and Bozorgmehr concluded that the Iranian Armenian ethnicity had a "special strength".[28]

According to Yeretzian's 1923 study, 39.5% of Los Angeles Armenians were skilled laborers, 23.5% were agricultural laborers, 2.3% were professionals, and the remainder worked in other occupations as laborers.[15]

Institutions

As of 1993, within the United States, the Los Angeles metropolitan area has the highest concentration of Armenian institutions and cultural programs. These institutions include businesses, restaurants, Armenian food stores, voluntary associations, clubs, radio programs, newspapers, television programs, nursing homes, churches, and Armenian American schools.[2]

The Organization of Istanbul Armenians Los Angeles (Armenian: Պոլսահայ Միություն), headquartered in a two story building in Winnetka in the San Fernando Valley region of Los Angeles, has a membership of over 1,000 ethnic Armenians who had origins in Turkey. The organization was established around 1976. In 1978 the membership was several dozen. The organization sponsors Doner Night.[29]

The Consulate-General of Armenia in Los Angeles (Armenian: Լոս Անջելեսում ՀՀ գլխավոր հյուպատոսության հասցեն է`[30]) is located in Glendale.[31]

The Montebello Genocide Memorial is located in Montebello.

Several Armenian voluntary associations had been established in Los Angeles by 1923.[3]

Culture

Dr. Seta Kazandjian described the community in her 2006 book as follows:

| “ | Waves of immigration into the Los Angeles area have resulted in the formation of strong communities in neighborhoods and cities such as Hollywood, Glendale. and North Hollywood. In these neighborhoods, an Armenian can live a very active social and occupational life and receive many services without speaking a word of English and interacting only with Armenians. Armenian-speaking food vendors, pharmacists, physicians, dentists, lawyers, tailors, hair stylists, shop owners and mechanics are all available. Up to three different 24-hour Armenian language television and radio channels are available. There are various social activities to attend for the Armenian community every day. Therefore, individuals exist who are not acculturated at all to the dominant American culture, as well as those who have chosen to separate from the Armenian community and acculturate completely, and many who are in the middle of acculturation spectrum.[32] | ” |

In 1993 Anny Bakalian, author of Armenian-Americans: From Being to Feeling Armenian, wrote that many poorer Armenians, especially low income refugees from the former Soviet Union and the Middle East who arrived in the 1980s, had been forced to take an Armenian identity.[2] He argued that many of the poor are not familiar with American customs and are uneducated, this therefore "risks increasing prejudice and discrimination against group members."[2] Bakalian stated his belief that "Los Angeles is not representative of Armenian-Americans or the Armenian-American community."[2]

As of 1980, 80% of Iranian Armenians have fellow Armenian Iranians at their social gatherings and as spouses and close friends. Iranian Armenian parents have proportionately higher numbers of Armenian friends compared to their children.[26]

Zankou Chicken has locations throughout the Los Angeles area.

Media

A bilingual English-Armenian telephone directory listing businesses and residences began publication in 1980.[2]

As of 1988 the Armenian-American The California Courier is published in Glendale on a weekly basis.[8]

In 2014, USArmenia TV began airing Glendale Life, a reality TV show about Armenians in Glendale. Critics of the show started a Facebook page called "Stop ‘Glendale Life’ Show" and a change.org petition. In a two-week span the petition got over 1,600 signatures and the Facebook page got almost 6,000 likes.[33]

Religion

As of 1994 there are Armenians in the area who are members of the Etchmiadzin-based and Beirut-based branches of Armenian Christianity. In addition there are members of other Christian faiths.[34]

As of 1993 the Los Angeles area had 22 Armenian churches.[15] The United Armenian Congregational Church in Cahuenga Pass had 1,000 active members as of 1994.[34]

In 1923 the Armenian Apostolic church was in existence.[3]

By 1923 the Armenian Gesthesmane Congregational Church, an Armenian Protestant church which had over 70 members that year, was in existence.[35]

The majority of Armenian churches established in Los Angeles by 1993 had been established after World War II.[15]

Former Governor of California George Deukmejian is an Armenian Episcopalian.[34]

Education

Claudia Der-Martirosian, Georges Sabagh, and Mehdi Bozorgmehr, authors of "Subethnicity: Armenians in Los Angeles," wrote that in 1980 "the general level of education among all Armenians in Los Angeles was fairly high."[23] Different subgroups of Armenian immigrants had differing levels of education. As of 1980, almost no U.S.-born Armenian men, and fewer of one out of ten Armenian-born Armenians and Iranian Armenians had low levels of education; these groups had the highest modal education category, with men achieving university degrees and women not having university degrees. Almost half of Turkish Armenian men, who were older compared to other Armenians, had some elementary school education. The modal education category of Turkish Armenians was the lowest, with both men and women having elementary education. Almost one quarter of Lebanese Armenian men and Armenian men from elsewhere in the Middle East had a limited elementary school education. Der-Martirosian, Sabagh, and Bozorgmehr wrote that "Although women, generally, had a lower educational achievement than did men, internal differences among subgroups were comparable to those of the Armenian men."[23] Because of the presence of uneducated Armenians, overall there were fewer Los Angeles Armenians with a postgraduate university education compared to those who had only an elementary level education.[23]

Primary and secondary education

Public schools

As of 1990, the largest immigrant group speaking an ethnic home language in the Glendale Unified School District was the Armenians.[36] In 1987 the district had eight Armenian-speaking teachers and teaching aides, and that year had hired five additional Armenian-speaking teachers and teacher aides.[8] By 2004 over 33% of the Glendale district students were Armenian. That year, due to high levels of student absence around the Armenian Christmas the Glendale district considered making Armenian holidays school holidays.[22]

As of 2010 20% of the students at Grant High School in Valley Glen (Los Angeles USD) were Armenian.[37]

Armenian schools

As of 1993 there were twelve Armenian day schools in the Los Angeles area, with five of them being high schools. These Los Angeles-area Armenian day schools are the majority of Armenian day schools in the United States.[15] Ferrahian Armenian School in Encino, Los Angeles in the San Fernando Valley is the first Armenian day school in the United States, opening in 1964.[38]

The Rose and Alex Pilibos Armenian School and the TCA Arshag Dickranian Armenian School are located in Little Armenia in Hollywood.

Armenian schools in the San Fernando Valley include the AGBU Manoogian-Demirdjian School in Winnetka, the Ferrahian Armenian School in Encino and North Hills.

Armenian schools in Pasadena include AGBU High School Pasadena.

The PK-12 Armenian Mesrobian School is located in Pico Rivera, serving the Armenian community east of Downtown Los Angeles.[39]

Armenian schools in Glendale include the Chamlian Armenian School.

Post-secondary education

The Mashdots College is located in Glendale. It includes college, career, and certificate programs.[40]

Events and memorials

Armenians in Los Angeles celebrate the Christmas under the Eastern Christianity dates. Armenians in Los Angeles do not have work holidays on the Eastern dates. The Armenian Christmas custom of families eating sweets, nuts, and dried fruit together has survived in Los Angeles.[41]

Events memorializing the Armenian genocide are held in the Los Angeles area. As of 2012 many such events were held in East Hollywood and Glendale.[42]

An Armenian genocide memorial opened in Grand Park in September 2016.[43]

Race relations

Armenians in the Los Angeles area have frequent contact with Hispanics and Latinos, including those of Mexican and Salvadoran origin. After Armenians moved into areas populated by Hispanics in the 1990s, racial tensions occurred at some area schools.[44]

Allegations of crime

In October 2010 the Federal Government of the United States accused 52 persons of being involved in a Medicare fraud operation orchestrated by an Armenian organized crime group; the persons were arrested. In February 2011 the federal government accused the Armenian Power gang of committing white collar crime. That month, 74 people were arrested in Southern California.[45] The federal authorities revealed the indictments at the Glendale police headquarters.[46] The charges were racketeering and fraud. Jason Wells and Veronica Rocha of the Glendale News-Press wrote that in Glendale, as a result of the 2011 arrests, "news of the arrests raised fears of what seems to be the inevitable: a rush by a vocal few to reinforce stereotypes."[47]

Notable residents

- Ben Agajanian (American football player)

- J. C. Agajanian (motorsports figure)

- George Deukmejian (Governor of California) – lived in Long Beach

- Mark Geragos (lawyer)

- Rob Kardashian

- Khloé Kardashian

- Kim Kardashian

- Kourtney Kardashian

- Robert Kardashian

- Bob Kevoian

- Daron Malakian (System of a Down)

- Rafi Manoukian (politician)

- Shavo Odadjian (System of a Down)

- Bill Paparian (politician)

- Cher (Cherilyn Sarkisian)

- Harry Sassounian (murderer convicted of the January 28, 1982 shooting of Kemal Ariken, the Consul General of Turkey to Los Angeles)[48]

- Zareh Sinanyan (mayor of Glendale, California)

- Serj Tankian (System of a Down)

- Bob Yousefian (politician)

- Larry Zarian (politician)

- John Dolmayan (System of a Down)

- Eric Bogosian (actor)

- Kirk Kerkorian (billionaire)

- Steve Sarkisian (former USC head football coach)

- Zildijian (drumming supply company)

References

- Bakalian, Anny. Armenian-Americans: From Being to Feeling Armenian (Armenian Research Center collection). Transaction Publishers, 1993. ISBN 1560000252, 9781560000259.

- Bozorgmehr, Mehdi, Claudia Der-Martirosian, and Georges Sabagh. "Middle Easterners: A New Kind of Immigrant" (Chapter 12). In: Waldinger, Roger and Mehdi Bozorgmehr (editors). Ethnic Los Angeles. Russell Sage Foundation, December 5, 1996. Start page 345. ISBN 1610445473, 9781610445474.

- Der-Martirosian, Claudia, Georges Sabagh, and Mehdi Bozorgmehr. "Subethnicity: Armenians in Los Angeles" (Chapter 11). In: Light, Ivan Huberta and Parminder Bhachu. Immigration and Entrepreneurship: Culture, Capital, and Ethnic Networks. Transaction Publishers, year unstated. Start page: 243. ISBN 1412825938, 9781412825931.

Notes

- 1 2 Bozorgmehr, Der-Martirosian, Sabagh, "Middle Easterners: A New Kind of Immigrant," p. 352.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bakalian, p. 429.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bakalian, p. 15.

- 1 2 3 Der-Martirosian, Sabagh, and Bozorgmehr, p. 247.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Der-Martirosian, Sabagh, and Bozorgmehr, "Subethnicity: Armenians in Los Angeles," p. 250.

- ↑

- 1 2 3 Texeira, Erin P. "Ethnic Friction Disturbs Peace of Glendale." Los Angeles Times. June 25, 2000. p. 1. Retrieved on March 24, 2014. "Armenians fleeing violence and oppression at home began arriving in Los Angeles around the 1940s. Most settled in Hollywood--once called "Little Armenia"--and aspired to homes in Glendale, among other cities."

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Arax, Mark and Esther Schrader. "County Braces for Sudden Influx of Soviet Armenians." Los Angeles Times. March 8, 1988. online page 1. Print: Vol.107, p.1. Available from Cengage Learning, Inc. Retrieved on July 2, 2014.

- ↑ Schrader, Esther. "Undertow: LA copes with the flood of Soviet emigres." The New Republic. December 4, 1989. Vol.201(23), p.11(2). ISSN 0028-6583. "[...]for many years home to the largest community of Armenians outside Yerevan.[...]Nine out of ten Armenians leaving the Soviet Union in the past two years have come here, joining relatives and friends."

- ↑ "Kobe Bryant’s deal with Turkish Airlines outrages Armenian Americans." Los Angeles Times. December 15, 2010. Retrieved on July 2, 2014.

- ↑ Gonzalez, David. "Following the Global Armenian Diaspora." The New York Times. April 24, 2014. Retrieved on July 2, 2014.

- 1 2 Der-Martirosian, Sabagh, and Bozorgmehr, "Subethnicity: Armenians in Los Angeles," p. 246.

- 1 2 Der-Martirosian, Sabagh, and Bozorgmehr, "Subethnicity: Armenians in Los Angeles," p. 248.

- ↑ Light, Ivan Hubert., and Parminder Bhachu. Immigration and Entrepreneurship: Culture, Capital, and Ethnic Networks. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction, 1993.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bakalian, p. 16.

- ↑ Brand, David. "Soviet Union Vision of Horror." TIME Magazine 26 Dec. 1988: n. pag. Web.

- 1 2 Clifford, Frank and Anne C. Roark. "Racial Lines in County Blur but Could Return: Population: Times study of census finds communities far more mixed. Some experts fear new ethnic divisions." Los Angeles Times. May 6, 1991. p. 2. Retrieved on March 24, 2014.

- 1 2 Talai, Vered Amit. "Armenians in London: The Management of Social Boundaries" (Issue 4 of Anthropological Studies of Britain/Armenian Research Center collection/Volume 4 of Studies on East Asia). Manchester University Press, 1989. ISBN 0719029279, 9780719029271. p. 93.

- ↑ Satzman, Darrell. "Zankou Chicken's tragic family rift impedes chain's growth." Los Angeles Times. March 18, 2010. Retrieved on July 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Council File: 00-1958 Title Little Armenia". City of Los Angeles Office of the City Clerk. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ↑ McCormick, Chris (April 4, 2016). "The Armenian Community of Glendale, California". The Atlantic. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- 1 2 Pang, Kevin. "Glendale Unified May Add Armenian Holiday." Los Angeles Times. February 8, 2004. Retrieved on July 2, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Der-Martirosian, Sabagh, and Bozorgmehr, "Subethnicity: Armenians in Los Angeles," p. 251.

- ↑ Bozorgmehr, Der-Martirosian, Sabagh, "Middle Easterners: A New Kind of Immigrant," p. 353.

- ↑ Der-Martirosian, Sabagh, and Bozorgmehr, "Subethnicity: Armenians in Los Angeles," p. 252.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Der-Martirosian, Sabagh, and Bozorgmehr, "Subethnicity: Armenians in Los Angeles," p. 253.

- ↑ Der-Martirosian, Sabagh, and Bozorgmehr, "Subethnicity: Armenians in Los Angeles," p. 252-253.

- ↑ Der-Martirosian, Sabagh, and Bozorgmehr, "Subethnicity: Armenians in Los Angeles," p. 255.

- ↑ Esquivel, Paloma. "A brotherhood is bolstered by food and friendship." Los Angeles Times. September 19, 2011. Retrieved on July 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Աշխատանքային օրեր և ժամեր" (Archive). Consulate-General of Armenia in Los Angeles. Retrieved on July 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Contacts, Office Hours & Holidays" (Archive) Consulate-General of Armenia in Los Angeles. Retrieved on July 2, 2014. "Consulate General of the Republic of Armenia in Los Angeles 346 N Central ave, Glendale, CA 91203"

- ↑ Kazandjian, Seta (2006). The Effects of Bilingualism and Acculturation on Neuropsychological Test Performance: A Study with Armenian Americans. ProQuest. pp. 27–28. ISBN 978-0-542-84512-3.

- ↑ Levine, Brittany. "Racy USArmenia reality-TV show faces criticism, boycott." Los Angeles Times. June 1, 2014. Retrieved on July 2, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Dart, John. "Christmas in January for Armenians : Religion: Karekin II, based in Beirut, officiates at ceremony at a congregation in Encino. Church is one of a handful that holds the observance early in the new year." Los Angeles Times. January 7, 1994. Retrieved on July 4, 2014.

- ↑ Bakalian, p. 15-16.

- ↑ Der-Martirosian, Sabagh, and Bozorgmehr, "Subethnicity: Armenians in Los Angeles," p. 250-251.

- ↑ Aghajanian, Liana. "Culture Clash: Armenian and Hispanic Relations in the Past, Present and Future" (Archive). Ararat Quarterly. July 6, 2010. Retrieved on January 5, 2016.

- ↑ Abram, Susan. "Armenian Realizes His Bicultural Goal." Los Angeles Times. August 17, 1997. Retrieved on July 4, 2014.

- ↑ Swartz, Kristen Lee. "Respecting Old-World Ways : Armenian School Puts Students in Touch With Their Roots." Los Angeles Times. June 10, 1993. Retrieved on March 24, 2014.

- ↑ Corrigan, Kelly. "Mashdots leader to lead visit to Western Armenia." Glendale News-Press. February 4, 2014. Retrieved on July 5, 2014. p. 2.

- ↑ Kim, Ann L. "Armenians Won't Rush Christmas." Los Angeles Times. January 6, 2000. Retrieved on July 2, 2014.

- ↑ Los Angeles Times Staff. "Armenian genocide commemoration events planned for L.A. region today." Los Angeles Times. April 24, 2012. Retrieved on July 2, 2014.

- ↑ Boxall, Bettina. "Memorial to Armenian genocide unveiled in L.A.'s Grand Park." Los Angeles Times. September 17, 2016. Retrieved on September 19, 2016.

- ↑ Aghajanian, Liana. "Culture Clash: Armenian and Hispanic Relations in the Past, Present and Future" (Archive). Ararat Quarterly. July 6, 2010. Retrieved on January 5, 2016.

- ↑ Blankenstein, Andrew and Kate Linthicum. "Raids targeting Armenian gang net 74 fraud suspects." Los Angeles Times. February 17, 2011. Retrieved on July 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Local Armenians fear rush to judgment after gang crackdown." Los Angeles Times. February 17, 2011. Retrieved on July 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Armenians uneasy after gang arrests." Glendale News-Press. February 16, 2011. Retrieved on July 2, 2014.

- ↑ Peterson, Merrill D. "Starving Armenians": America and the Armenian Genocide, 1915–1930 and After (Armenian Research Center collection). University of Virginia Press, 2004. ISBN 0-8139-2267-4, 9780813922676. p. 166.

Further reading

- Sabagh, Georges, Mehdi Bozorgmehr, and Claudia Der-Martirosian. Subethnicity: Armenians in Los Angeles. Institute for Social Science Research, University of California, Los Angeles, 1990. Available in snippet form at Google Books.

- Hovanessian, Seboo. An Assimilative Profile of American-Armenians in Los Angeles. California State University, Northridge, 1993.

- Yeretzian, Aram Serkis. "A history of Armenian immigration to America with special reference to conditions in Los Angeles." 1974, ISBN 9780882472669, viii, 78 - See record at the University of Southern California

External links

- Armenian Society of Los Angeles

- Organization of Istanbul Armenians Los Angeles

- Consulate-General of Armenia in Los Angeles

- "Community Institutions." Consulate-General of Armenia in Los Angeles.