History of sport

The history of sports may extend as far back as the beginnings of military training, with competition used as a means to determine whether individuals were fit and useful for service. Team sports may have developed to train and to prove the capability to fight and work together as a team (army). The history of sport can teach us about social changes and about the nature of sport itself, as sport seems involved in the development of basic human skills. Of course, as one goes further back in history, dwindling evidence makes theories of the origins and purposes of sport more and more difficult to support.

Sport in prehistory

Cave paintings have been found in the Lascaux caves in France that have been suggested to depict sprinting and wrestling in the Upper Paleolithic around 15,300 years ago.[1][2] Cave paintings in the Bayankhongor Province of Mongolia dating back to Neolithic age of 7000 BCE show a wrestling match surrounded by crowds.[3] Neolithic Rock art found at the cave of swimmers in Wadi Sura, near Gilf Kebir in Libya has shown evidence of swimming and archery being practiced around 6000 BCE.[4] Prehistoric cave paintings have also been found in Japan depicting a sport similar to sumo wrestling.[5]

Ancient Sumer

Various representations of wrestlers have been found on stone slabs recovered from the Sumerian civilization.[7] One showing three pairs of wrestlers was generally dated to around 3000 BCE.[8] A cast Bronze figurine,[9] (perhaps the base of a vase) has been found at Khafaji in Iraq that shows two figures in a wrestling hold that dates to around 2600 BCE. The statue is one of the earliest depictions of sport and is housed in the National Museum of Iraq.[10][11] The origins of boxing have also been traced to ancient Sumer.[8] The Epic of Gilgamesh gives one of the first historical records of sport with Gilgamesh engaging in a form of belt wrestling with Enkidu. The cuneiform tablets recording the tale date to around 2000 BCE, however the historical Gilgamesh is supposed to have lived around 2800 to 2600 BCE.[12] The Sumerian king Shulgi also boasts of his prowess in sport in Self-praise of Shulgi A, B and C.[12] Fishing hooks not unlike those made today have been found during excavations at Ur, showing evidence of angling in Sumer at around 2600 BCE.[13]

Ancient Egypt

Monuments to the Pharaohs found at Beni Hasan dating to around 2000 BCE[14] indicate that a number of sports, including wrestling, weightlifting, long jump, swimming, rowing, flying, shooting, fishing[13] and athletics, as well as various kinds of ball games, were well-developed and regulated in ancient Egypt. Other Egyptian sports also included javelin throwing, high jump, and snooker.[15] An earlier portrayal of figures wrestling was found in the tomb of Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum in Saqqara dating to around 2400 BCE.[6][16]

Ancient Greece

Depictions of ritual sporting events are seen in the Minoan art of Bronze Age Crete, such as a fresco dating to 1500 BCE of gymnastics in the form of religious bull-leaping and possibly bullfighting. The origins of Greek sporting festivals may date to funeral games of the Mycenean period, between 1600 BCE and c. 1100 BCE.[17] In the Iliad there are extensive descriptions of funeral games held in honour of deceased warriors, such as those held for Patroclus by Achilles. Engaging in sport is described as the occupation of the noble and wealthy, who have no need to do manual labour themselves. In the Odyssey, king Odysseus of Ithaca proves his royal status to king Alkinoös of the Phaiakes by showing his proficiency in throwing the javelin. It was predictably in Greece that sports were first instituted formally, with the first Olympic Games recorded in 776 BCE in Olympia, where they were celebrated until 393 CE. The games were held every four years, or Olympiad, which became a unit of time in historical chronologies. Initially a single sprinting event, the Olympics gradually expanded to include several footraces, run in the nude or in armor, boxing, wrestling, pankration, chariot racing, long jump, javelin throw, and discus throw. During the celebration of the games, an Olympic Truce was enacted so that athletes could travel from their countries to the games in safety. The prizes for the victors were wreaths of laurel leaves. Other important sporting events in ancient Greece were the Isthmian games, the Nemean Games, and the Pythian Games. Together with the Olympics, these were the most prestigious games, and formed the Panhellenic Games. Some games, e.g. the Panathenaia of Athens, included musical, reading and other non-athletic contests in addition to regular sports events. The Heraean Games were the first recorded sporting competition for women, held in Olympia as early as the 6th century BCE.

Ancient sports elsewhere

Sports that are at least two and a half thousand years old include hurling in Ancient Ireland, shinty in Scotland, harpastum (similar to rugby) in Rome, cuju (similar to association football) in China, and polo in Persia. The Mesoamerican ballgame originated over three thousand years ago. The Mayan ballgame of Pitz is believed to be the first ball sport, as it was first played around 2500 BCE.There are artifacts and structures that suggest that the Chinese engaged in sporting activities as early as 2000 BCE.[18] Gymnastics appears to have been a popular sport in China's ancient past. Ancient Persian sports such as the traditional Iranian martial art of Zourkhaneh. Among other sports that originated in Persia are polo and jousting. A polished bone implement found at Eva in Tennessee, United States and dated to around 5000 BCE has been construed as a possible sporting device used in a "ring and pin" game.[8]

Middle Ages

For at least one hundred years, entire villages have competed with each other in rough, and sometimes violent, ballgames in England (Shrovetide football) and Ireland (caid). In contrast, the game of calcio Fiorentino, in Florence, Italy, was originally reserved forth combat sports such as fencing and jousting being popular. Horse racing, in particular, was a favourite of the upper class in Great Britain, with Queen Anne founding the Ascot Racecourse.

Development of modern sports

.jpg)

Some historians – most notably Bernard Lewis – claim that team sports as we know them today are primarily an invention of Western culture. British Prime Minister John Major was more explicit in 1995:

- We invented the majority of the world's great sports.... 19th century Britain was the cradle of a leisure revolution every bit as significant as the agricultural and industrial revolutions we launched in the century before.[19]

The traditional teams sports are seen as springing primarily from Britain, and subsequently exported across the vast British Empire. This can be seen as either discounting some of the ancient games of cooperation from Asia (e.g. polo, numerous martial arts forms, and various, now assimilated football varieties) and even from the Americas (e.g. lacrosse), or as the suggestion that while these sports did exist modern team sports did not directly derive from them. European colonialism certainly helped spread particular games around the world, especially cricket (not related to baseball), football of various sorts, bowling in a number of forms, cue sports (like snooker, carom billiards and pool), hockey and its derivatives, equestrian (originally of Middle Eastern origin), and tennis (and related games deriving from jeu de paume), and many winter sports, while the originally Europe-dominated modern Olympic Games generally also ensured standardization in particularly European directions when rules for similar games around the world were merged.[20] Regardless of game origins, the Industrial Revolution and mass production brought increased leisure which allowed more time to engage in playing or observing (and gambling upon) spectator sports, as well as less elitism in and greater accessibility of sports of many kinds. With the advent of mass media and global communication, professionalism became prevalent in sports, and this furthered sports popularity in general. With the increasing values placed on those who won also came the increased desire to cheat. Some of the most common ways of cheating today involve the use of performance-enhancing drugs such as steroids. The use of these drugs has always been frowned on but in recent history there have also been agencies set up to monitor professional athletes and ensure fair play in the sport.

England

Writing about cricket in particular, John Leech (2005a) has explained the role of Puritan power, the English Civil War, and the Restoration of the monarchy in England. The Long Parliament in 1642 "banned theatres, which had met with Puritan disapproval. Although similar action would be taken against certain sports, it is not clear if cricket was in any way prohibited, except that players must not break the Sabbath". In 1660, "the Restoration of the monarchy in England was immediately followed by the reopening of the theatres and so any sanctions that had been imposed by the Puritans on cricket would also have been lifted."[21] He goes on to make the key point that political, social and economic conditions in the aftermath of the Restoration encouraged excessive gambling, so much so that a Gambling Act was deemed necessary in 1664. It is certain that cricket, horse racing and boxing (i.e., prizefighting) were financed by gambling interests. Leach explains that it was the habit of cricket patrons, all of whom were gamblers, to form strong teams through the 18th century to represent their interests. He defines a strong team as one representative of more than one parish and he is certain that such teams were first assembled in or immediately after 1660. Prior to the English Civil War and the Commonwealth, all available evidence concludes that cricket had evolved to the level of village cricket only where teams that are strictly representative of individual parishes compete. The "strong teams" of the post-Restoration mark the evolution of cricket (and, indeed of professional team sport, for cricket is the oldest professional team sport) from the parish standard to the county standard. This was the point of origin for major, or first-class, cricket. The year 1660 also marks the origin of professional team sport.

A number of the public schools such as Winchester and Eton, introduced variants of football and other sports for their pupils. These were described at the time as "innocent and lawful", certainly in comparison with the rougher rural games. With urbanization in the 19th century, the rural games moved to the new urban centres and came under the influence of the middle and upper classes. The rules and regulations devised at English institutions began to be applied to the wider game, with governing bodies in England being set up for a number of sports by the end of the 19th century. The rising influence of the upper class also produced an emphasis on the amateur, and the spirit of "fair play". The industrial revolution also brought with it increasing mobility, and created the opportunity for universities in Britain and elsewhere to compete with one another. This sparked increasing attempts to unify and reconcile various games in England, leading to the establishment of the Football Association in London, the first official governing body in football.

For sports to become professionalized, coaching had to come first. It gradually professionalized in the Victorian era and the role was well established by 1914. In the First World War, military units sought out the coaches to supervise physical conditioning and develop morale-building teams.[22]

The British Empire and post-colonial sports

The influence of British sports and their codified rules began to spread across the world in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, particularly association football. A number of major teams elsewhere in the world still show these British origins in their names, such as AC Milan in Italy, Grêmio Foot-Ball Porto Alegrense in Brazil, and Athletic Bilbao in Spain. Cricket became popular in several of the nations of the then British Empire, such as Australia, South Africa, India and Pakistan, and remain popular in and beyond today's Commonwealth of Nations. The revival of the Olympic Games by Baron Pierre de Coubertin was also heavily influenced by the amateur ethos of the English public schools.[23] The British played a major role in defining amateurism, professionalism, the tournament system and the concept of fair play.[24] Some sports developed in England, spread to other countries and then lost its popularity in England while remaining actively played in other countries, a notable example being bandy which remains popular in Finland, Kazakhstan, Norway, Russia, and Sweden.[25]

Baseball (closely related to English rounders and French la soule, and less clearly connected to cricket) became established in the urban Northeastern United States, with the first rules being codified in the 1840s, while American football was very popular in the south-east, with baseball spreading to the south, and American football spreading to the north after the Civil War. In the 1870s the game split between the professionals and amateurs; the professional game rapidly gained dominance, and marked a shift in the focus from the player to the club. The rise of baseball also helped squeeze out other sports such as cricket, which had been popular in Philadelphia prior to the rise of baseball.

American football (and gridiron football more generally) also has its origins in the English variants of the game, with the first set of intercollegiate football rules based directly on the rules of the Football Association in London. However, Harvard chose to play a game based on the rules of Rugby football. Walter Camp would then heavily modify this variant in the 1880s, with the modifications also heavily influencing the rules of Canadian football.

World-wide, the British influence certainly includes many different football codes, lawn bowls, lawn tennis and other sports. The major impetus for this was the patenting of the world's first lawnmower in 1830. This allowed for the preparation of modern ovals, playing fields, pitches, grass courts, etc.[26]

The 21st century has seen a move towards adventure sports as a form of individual escapism, transcending the routines of life. Examples include white water rafting, paragliding, canyoning, base jumping and more genteelly, orienteering.

Women's sport history

Women's competition in sports has been frowned upon by many societies in the past. The English public-school background of organised sport in the 19th and early 20th century led to a paternalism that tended to discourage women's involvement in sports, with, for example, no women officially competing in the 1896 Olympic Games. The 20th century saw major advances in the participation of women in sports, although women's participation as fans, administrators, officials, coaches, journalists, and athletes remains in general less than men's. The increase in girls’ and women’s’ participation in sport has been partly influenced by the women's rights and feminist movements of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, respectively. In the United States, female students’ participation in sports was significantly boosted by the Title IX Act in 1972, which forbade gender discrimination in all aspects of any educational environment that uses federal financial aid,[27] leading to increased funding [28] and support to develop female athletes.

Pressure from sports funding bodies has also improved gender equality in sports. For example, the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) and the Leander Rowing Club in England had both been male-only establishments since their founding in 1787 and 1818, respectively, but both opened their doors to female members at the end of the 20th century at least partially due to the requirements of the United Kingdom Lottery Sports Fund.

The 21st century has seen women’s participation in sport at its all-time highest. At the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, women competed in 27 sports over 137 events, compared to 28 men’s sports in 175 events.[29] Several national women's professional sports leagues have been founded and are in competition, and women’s international sporting events such as the FIFA Women's World Cup, Women's Rugby World Cup, and Women's Hockey World Cup continue to grow.

Stadium through the ages

- The Olympia stadium

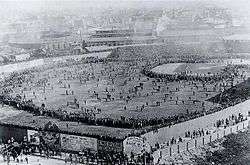

The Huntington Avenue Grounds during the 1903 World Series, United States

The Huntington Avenue Grounds during the 1903 World Series, United States Rogers Centre, the first functional retractable-roof stadium, Canada

Rogers Centre, the first functional retractable-roof stadium, Canada%2C_16_April_2012.jpg) London Olympic Stadium, United Kingdom

London Olympic Stadium, United Kingdom The Grand Ballcourt of Chichen Itza

The Grand Ballcourt of Chichen Itza

See also

- Sport in the United Kingdom § History

- Sport in England

- History of sport in Australia

- History of sports in Canada

- History of sport in the United States

- Nationalism and sport

- Sociology of sport

References

- ↑ Capelo, Holly (July 2010). "Symbols from the Sky: Heavenly messages from the depths of prehistory may be encoded on the walls of caves throughout Europe.". Seed Magazine. Retrieved January 2011. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Gary Barber (1 February 2007). Getting Started in Track and Field Athletics: Advice & Ideas for Children, Parents, and Teachers. Trafford Publishing. pp. 25–. ISBN 978-1-4120-6557-3. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ↑ Hartsell, Jeff., Wrestling 'in our blood,' says Bulldogs' Luvsandorj, 17 March 2011

- ↑ Győző Vörös (2007). Egyptian Temple Architecture: 100 Years of Hungarian Excavations in Egypt, 1907-2007. American Univ in Cairo Press. pp. 39–. ISBN 978-963-662-084-4. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ↑ Robert Crego (2003). Sports and Games of the 18th and 19th Centuries. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 34–. ISBN 978-0-313-31610-4. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- 1 2 Egypt Thomb. Lessing Photo. 02-15-2011.

- ↑ Harriet Crawford (16 September 2004). Sumer and the Sumerians. Cambridge University Press. pp. 247–. ISBN 978-0-521-53338-6. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- 1 2 3 Kendall Blanchard (1995). The Anthropology of Sport: An Introduction. ABC-CLIO. pp. 99–. ISBN 978-0-89789-330-5. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ↑ Time Inc (15 August 1938). LIFE. Time Inc. pp. 59–. ISSN 0024-3019. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ↑ Faraj Baṣmahʹjī (1975). Treasures of the Iraq Museum. Al-Jumhuriya Press. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ↑ David Gilman Romano (1993). Athletics and Mathematics in Archaic Corinth: The Origins of the Greek Stadion. American Philosophical Society. pp. 10–. ISBN 978-0-87169-206-1. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- 1 2 Nigel B. Crowther (2007). Sport in Ancient Times. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 15–. ISBN 978-0-275-98739-8. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- 1 2 Terry Hellekson (19 November 2005). Fish Flies: The Encyclopedia Of The Fly Tier's Art. Gibbs Smith. pp. 2–. ISBN 978-1-58685-692-2. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ↑ W. J. Hamblin (12 April 2006). Warfare in Ancient Near East. Taylor & Francis. pp. 433–. ISBN 978-0-415-25588-2. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ↑ William J. Baker (1 July 1988). Sports in the Western World. University of Illinois Press. pp. 8–. ISBN 978-0-252-06042-7. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ↑ Michael Rice (7 November 2001). Who's Who in Ancient Egypt. Psychology Press. pp. 98–. ISBN 978-0-415-15449-9. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ↑ Wendy J. Raschke (15 June 1988). Archaeology Of The Olympics: The Olympics & Other Festivals In Antiquity. Univ of Wisconsin Press. pp. 22–. ISBN 978-0-299-11334-6. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- ↑ "Sports History in China".

- ↑ Garry Whannel (2005). Media Sport Stars: Masculinities and Moralities. Routledge. p. 72.

- ↑ "Britain's Living Legacy to the Games: Sports". The New York Times. 26 July 2012. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ↑ Leach (2005a) is a heavily annotated chronology of cricket 1300-1730 and the source for numerous entries here.

- ↑ Dave Day, Professionals, Amateurs and Performance: Sports Coaching in England, 1789–1914 (2012)

- ↑ Harold Perkin, "Teaching the nations how to play: sport and society in the British empire and Commonwealth." The International Journal of the History of Sport 6.2 (1989): 145-155.

- ↑ Sigmund Loland, "Fair play in sports contests-a moral norm system." Sportwissenschaft 21.2 (1991): 146-162.

- ↑ "Svenska Bandyförbundet, bandyhistoria 1875–1919". Iof1.idrottonline.se. 1 February 2013. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ↑ Australian Broadcasting Corporation's Radio National Ockham's Razor, first broadcast 6 June 2010.

- ↑ Britt, M. & Timmerman, M. 'Title IX and Higher Education: The Implications for the 21st Century' in "Franklin Business and Law Journal", Vol. 2014, No. 1. (March, 2014), pp. 83-86.

- ↑ Reinbrecht, E. 'Northwestern University and Title IX: One Step Forward for Football Players, Two Steps Back for Female Student Athletes' in "University of Toledo Law Review", Vol. 47, No. 1. (September, 2015), pp. 243-277.

- ↑ Pfister, G. 'Outsiders: Muslim Women and Olympic Games - Barriers and Opportunities' in "The International Journal of the History of Sport", Vol. 27, Nos. 16-18. (November–December, 2010), pp. 2925-2957.

Further reading

- Day, Dave. Professionals, Amateurs and Performance: Sports Coaching in England, 1789–1914 (2012)

- Gorn, Elliott J. A Brief History of American Sports (2004)

- Guttmann, Allen. Women's Sports: A History, Columbia University Press 1992

- Guttmann, Allen. Games and Empires: Modern Sports and Cultural Imperialism, Columbia Univ Press, 1996

- Guttmann, Allen. The Olympics: A History of the Modern Games (2002)

- Holt Richard. Sport and Society in Modern France (1981).

- Holt Richard. Sport and the British: A Modern History (1990) excerpt

- Howell, Colin. Blood, Sweat, and Cheers: Sport and the Making of Modern Canada (2001)

- Mangan, J.A. (1996). Militarism, Sport, Europe: War Without Weapons. Routledge.

- Maurer, Michael. "Vom Mutterland des Sports zum Kontinent: Der Transfer des englischen Sports im 19. Jahrhundert", European History Online, Mainz, 2011, retrieved: 25 February 2012.

- Morrow, Don and Kevin B. Wamsley. Sport in Canada A History (2009)

- Murray, Bill. The World'S Game: A History of Soccer (1998)

- Polley, Martin. Sports History: a practical guide, Palgrave, 2007.

- Scott A.G.M. Crawford (Hrg.), Serious sport : J.A. Mangan's contribution to the history of sport, Portland, OR : Frank Cass, 2004

- Pope, S.W. ed. The new American sport history : recent approaches and perspectives, Univ. of Illinois Press, 1997

Journals

- online article from The Sports Historian 1993-2001

- European Studies in Sport History

- The International Journal of the History of Sport

- Journal of Sport History

- STAPS. International Journal of Sport science and physical education, Bruxelles, De Boeck.

- Sport History Journal

- Sport in History

- STADION International Journal of Sport History