History of skiing

Skiing, or traveling over snow on skis, has a history of at least five millennia. The earliest archaeological examples of skis were found in Russia and date to 5000 BCE.[1] Although modern skiing has evolved from beginnings in Scandinavia, 10,000-year-old wall paintings suggest use of skis in the Xinjiang region of what is now China. Originally purely utilitarian, starting in the mid-1800s skiing became a popular recreational activity and sport, becoming practiced in snow-covered regions worldwide, and providing crucial economic support to purpose-built ski resorts and communities.[2]

Etymology and usage

The word ski comes from the Old Norse word "skíð" which means stick of wood or ski.[3] The word "ski" has a wider meaning in Norwegian, for instance "vedski" meaning "splitwood for making fire" or "skigard" meaning "a wooden split-rail fence".[4]

In modern Norwegian this word is usually pronounced [ˈʃiː]. English and French use the original spelling "ski", and modify the pronunciation. In Italian it is pronounced as in Norwegian, and the spelling is modified: "sci". German, Portuguese and Spanish adapt the word to their linguistic rules; "Schifahren"/"Schilaufen" (however there is a form- Ski), "esqui" and "esquí". Many languages make a verb form out of the noun, such as "to ski" in English, "skier" in French, "esquiar" in Portuguese and Spanish, "sciare" in Italian, or "schifahren" (as above) in German which is not possible in Norwegian. In Swedish, a close relation to Norwegian, the word is "skidor" (pl.).

Finnish has its own ancient words for skis and skiing. In Finnish ski is suksi and skiing is hiihtää. The Sami also have their own words for skis and skiing. For example, the Lule Sami word for ski is "sabek" and skis are "sabega".

Early archaeological evidence

The oldest information about skiing is based on archaeological evidence. Two regions present the earliest evidence of skis and their use: the Altaic region of modern China where 10,000-year-old paintings suggest the aboriginal use of skis,[5][6] and northern Russia, where the oldest fragments of ski-like objects, dating from about 6300–5000 BCE were found about 1,200 km northeast of Moscow at Lake Sindor.[7]

The earliest Scandinavian examples of skiing date to 5000 BCE with primitive carvings, which depict a skier with one pole, found in Rødøy in the Nordland region of Norway. Rock drawings in Norway dated at 4000 BC[8] depict a man on skis holding a stick. The first primitive Scandinavian ski was found in a peat bog in Hoting in Jämtland County in Sweden which dates back to 4500 or 2500 BCE. Noted examples are the Kalvträskskidan ski, found in Sweden and dated to 3300 BCE, and the Vefsn Nordland ski, found in Norway and dated to 3200 BC.[9] A ski excavated in Greenland is dated to 1010.[10]

In 2014, a ski complete with leather bindings, emerged from a glacier in Reinheimen mountains, Norway. The binding is at a small elevated area in the middle of the 172 cm long and 14,5 cm wide ski. According to the report the ski is some 1300 years old. A large number of organic artifacts have been well preserved for several thousand years by the stable glaciers of Oppland county and emerge when glaciers recede.[11]

Skiing as transportation

Norse mythology describes the god Ullr and the goddess Skaði hunting on skis. Early historical evidence includes Procopius' (around CE 550) description of Sami people as skrithiphinoi translated as "ski running samis".[12] Birkely argues that the Sami people have practiced skiing for more than 6000 years, evidenced by the very old Sami word čuoigat for skiing.[13] Egil Skallagrimsson's 950 CE saga describes King Haakon the Good's practice of sending his tax collectors out on skis.[14] The Gulating law (1274) stated that "No moose shall be disturbed by skiers on private land."[12]

Ski warfare, the use of ski-equipped troops in war, is first recorded by the Danish historian Saxo Grammaticus in the 13th century. The speed and distance that ski troops are able to cover is comparable to that of light cavalry. Swedish writer Olaus Magnus's 1555 A Description of the Northern Peoples describes skiers and their climbing skins in Scricfinnia in what is now Norway.[15] The garrison in Trondheim used skis at least from 1675, and the Danish-Norwegian army included specialized skiing battalions from 1747 – details of military ski exercises from 1767 are retained.[16] Skis were used in military exercises in 1747.[17] In 1799 French traveller Jacques de la Tocnaye visits Norway and writes in his travel diary:[18]

| “ | In winter, the mail is transported through Filefjell mountain pass by a man on a kind of snow skates moving very quickly without being obstructed by snow drifts that would engulf both people and horses. People in this region move around like this. I've seen it repeatedly. It requires no more effort than what is needed to keep warm. The day will surely come when even those of other European nations are learning to take advantage of this convenient and cheap mode of transport. | ” |

Norwegian immigrants used skis ("Norwegian snowshoes") in the US midwest from around 1836. Norwegian immigrant "Snowshoe Thompson" transported mail by skiing across the Sierra Nevada between California and Nevada from 1856.[12] In 1888 Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen and his team crossed the Greenland icecap on skis. Norwegian workers on the Buenos Aires - Valparaiso railway line introduced skiing in South America around 1890.[12] In 1910 Roald Amundsen used skis on his South Pole Expedition. In 1902 the Norwegian consul in Kobe imported ski equipment and introduced skiing to the Japanese, motivated by the death of Japanese soldiers during snow storm.[12]

Skiing as sport

The first recorded organized skiing exercises and races are from military uses of skis in Norwegian and Swedish infantries. For instance details of military ski exercises in the Danish-Norwegian army from 1767 are retained: Military races and exercises included downhill in rough terrain, target practice while skiing downhill, and 3 km cross-country skiing with full military backpack.[16]

- 1809: Olaf Rye: first known ski jumper.

- 1843: First public skiing competition ("betting race") held in Tromsø, Norway on March 19, 1843. Also the first skiing competition reported in a newspaper.[12]

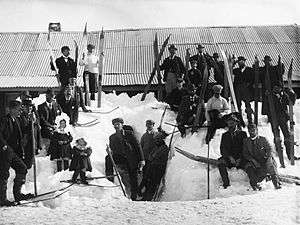

- 1861: First ski clubs: Inderøens Skiløberforening founded in the Trøndelag region of Norway[19] (possibly in 1862). Trysil Skytte- og Skiløberforning founded 20 May 1861 in Trysil.[20] Skiing established in Australia at Kiandra, which led to the founding of the Kiandra Snow Shoe Club.[21] Ski racing as an organised sport commences in America[22]

- 1862: First public ski jumping competition held at Trysil, Norway, January 22, 1862. Judges awarded points for style ("elegance and smoothness").[12]

- 1863: First recorded female ski jumper at Trysil competition.[12]

- 1864: From January 1864 "Trondheim Weapons Training Club" organizes regular training and competition races (cross-country and jumping), in Trondheim, Norway.[12]

- 1872: The oldest ski club in North America still existing is the Nansen Ski Club,[23] which was founded in 1872 by Norwegian immigrants of Berlin, New Hampshire under a different name.[24]

- 1878: On the occasion of the Exposition Universelle in Paris, the Norwegian pavilion presents a display of skis. This ancestral means of locomotion draws the attention of visitors who buy many of them. Henry Duhamel experiments with a pair at Chamrousse in the Alps.[25][26][27]

- 1879: first recorded use of the word slalom.[28]

- 1884: First pure cross-country competition held in Trondheim when ski jumping was dropped from the annual competition.[29]

- 1893: Henrik Angell introduces skiing in Montenegro.

- November 1895: creation of the Ski Club des Alpes in Grenoble by the friends of Henry Duhamel to whom he had distributed fourteen pairs of skis acquired during his trip to Finland

- 1904: First ski race in Italy, at Bardonecchia.[16]

- 1905: foundation of the U.S. Ski and Snowboard Association.[30]

- 1905/1906: The notion of "slalom" ("slalåm") used for the first time at a race in Sonnenberg. Skiing between poles with flags called "Wertungsfahren" at Münchenkuggel.[16]

- 1908: The Kiandra Snow Shoe Club of Australia holds an "international contest" of "ski running".[31]

- 1922: start of the Vasaloppet.

- 1924: formation of the International Ski Federation, also the first Winter Olympics.

- 1929: Norwegian instructors arrive in Sapporo and train Japanese in ski jumping.[12]

- 1932: start of the Birkebeinerrennet

- 1952 Winter Olympics.: Women’s Nordic skiing debuts

- Paralympic cross-country skiing debuts at the 1976 Winter Paralympics.

- 1992: Mogul skiing and Freestyle skiing added to the 1992 Winter Olympics.

- 2002 Winter Olympics: Appearance of sprint and mass start cross-country events in Salt Lake City.

- 2009: campaign for the inclusion of women's ski jumping leads to its inclusion in the 2014 Winter Olympics.[32]

Skiing as recreation

.jpg)

- 1849: First public "ski tour" organized in Trondheim, Norway.[12]

- 1868: Mountain resorts became commercially viable when city-dwellers could reach them in winter by train.[33]

- 1901 : First skiing in the Pyrénées on January 29 at La Llagonne (Pyrénées-Orientales, France).[34]

- 1910: first rope tow.[35]

- 1936: The first chair lift is introduced at Sun Valley, Idaho

- 1939: the Sno-Surf is patented in the USA. Made of solid white oak, it had an adjustable strap for the left foot, a rubber mat to hold the right foot, a rope with loop used to control speed and steer, and a guide stick used to steer. The first commercially successful, precursor to the snowboard, the snurfer was introduced in 1965.[36]

- 1952: The first major commercial snow-making machinery installed at Grossinger's Catskill Resort Hotel in New York state, USA.[37]

- 1970s: Telemark skiing undergoes a revival possibly inspired by Stein Eriksen and his book Come Ski With Me.[38]

Evolution of equipment

Skis

Asymmetrical skis were used at least in northern Finland and Sweden up until the 1930s.[39] On one leg the skier wore a long straight non-arching ski for sliding, and on the other a shorter ski for kicking. The bottom of the short ski was either plain or covered with animal skin to aid this use, while the long ski supporting the weight of the skier was treated with animal fat in similar manner to modern ski waxing. Early record of this type of skis survives in works of Olaus Magnus.[40] He associates them to Sami people and gives Sami names of savek and golos for the plain and skinned short ski. Finnish names for these are lyly and kalhu for long and short ski.

The seal hunters at the Gulf of Bothnia had developed a special long ski to sneak into shooting distance to the seals' breathing holes, though the ski was useful in moving in the packed ice in general and was made specially long, 3–4 meters, to protect against cracks in the ice. This is called skredstång in Swedish.[41]

Around 1850 artisans in Telemark, Norway invent the cambered ski. This ski arches up in the middle, under the binding, which distributes the skier's weight more evenly across the length of the ski. Earlier plank-style skis had to be thick enough not to bow downward and sink in the snow under the skier’s weight.[42] Norheim's ski was also the first with a sidecut that narrowed the ski underfoot while the tip and tail remained wider. This enabled the ski to flex and turn more easily.[42]

In 1950 Howard Head introduced the Head Standard, constructed by sandwiching aluminum alloy around a plywood core. The design included steel edges (invented in 1928 in Austria,[42]) and the exterior surfaces were made of phenol formaldehyde resin which could hold wax. This hugely successful ski was unique at the time in having been designed for the recreational market, rather than for racing.[43] 1962: a fibreglass ski, Kneissl's White Star, was used by Karl Schranz to win two gold medals at the FIS Alpine World Ski Championships.[43] By the late '60s fibreglass had mostly replaced aluminum.

In 1975 the torsion box ski construction design is patented.[44] The patent is referenced by Kästle, Salomon, Rottefella, and Madshus. In 1993 Elan introduced the Elan SCX. These introduced a new ski geometry, common today, with a much wider tip and tail than waist. When tipped onto their edges, they bend into a curved shape and carve a turn. Other companies quickly followed suit, and it was realized in retrospect that "It turns out that everything we thought we knew for forty years was wrong."[42] The Twin-tip ski was introduced by Line in 1995.[45]

Bindings

In the early days of skiing the binding was also similar to those of a contemporary snowshoe, generally consisting of a leather strap fastened over the toe of the boot. In the 1800s, skiing evolved into a sport and the toe strap was replaced by a metal clip under the toe. This provided much greater grip on the boot, allowing the ski to be pushed sideways. The heel strap also changed over time; in order to allow a greater range of motion, a spring was added to allow the strap to lengthen when the boot was rotated up off the ski.

This buckled strap was later replaced by a metal cable.[46] The cable binding remained in use, and even increased in popularity, throughout this period as cross-country skiing developed into a major sport of its own. Change eventually came though the evolution of the Rottefella binding, first introduced in 1927. The original Rottefella eliminated the heel strap, which held the boot forward in the binding, by drilling small holes in the sole of the boot which fit into pins in the toe piece. This was standardized as the 3-pin system, which was widespread by the 1970s.[47] It has now generally been replaced by the NNN system.

The introduction of ski lifts in 1908 led to an evolution of skiing as a sport. In the past, skiers would have to ski or walk up the hills they intended to ski down. With the lift, the skiers could leave their skis on, and would be skiing downhill all the time. The need to unclip the heel for cross-country use was eliminated, at least at resorts with lifts. As lifts became more common, especially with the introduction of the chairlift in 1936, the ski world split into cross-country and downhill, a split that remains to this day.

In 1937 Hjalmar Hvam broke his leg skiing, and while recuperating from surgery, invented the Saf-Ski toe binding.[48]

Boots

Ski boots were leather winter boots, held to the ski with leather straps. As skiing became more specialized, so too did ski boots, leading to the splitting of designs between those for alpine skiing and cross-country skiing.

Modern skiing developed as an all-round sport with uphill, downhill and cross-country portions. The introduction of the cable binding started a parallel evolution of binding and boot.[49] Boots with the sole extended rearward to produce a flange for the cable to firmly latch became common, as did designs with semi-circular indentations on the heel for the same purpose.

With the introduction of ski lifts, the need for skiing to get to the top of the hill was eliminated, and a much stiffer design was preferred, providing better control over the ski when sliding downhill.

Glide and grip

Johannes Scheffer in Argentoratensis Lapponiæ (History of Lapland) in 1673 probably gave the first recorded instruction for ski wax application[50] He advised skiers to use pine tar pitch and rosin. Ski waxing was also documented in 1761.[51]

1934 saw limited production of solid aluminum skis in France. Wax does not stick to aluminum, so the base under the foot included grips to prevent backsliding, a precursor of modern fish scale waxless skis.[52] In 1970 waxless Nordic skis were made with fishscale bases.[43] Klister, a sticky material, which provides grip on snow of all temperatures that has become coarse-grained as a result of multiple freeze-thaw cycles or wind packing, was invented and patented in 1913 by Peter Østbye.[53] Recent advancements in wax have been the use of surfactants, introduced in 1974 by Hertel Wax, and fluorocarbons, introduced in 1986, to increase water and dirt repellency and increase glide. Many companies, including Swix, Toko, Holmenkol, Briko, and Maplus are dedicated to ski wax production and have developed a range of products to cover various conditions.

Poles

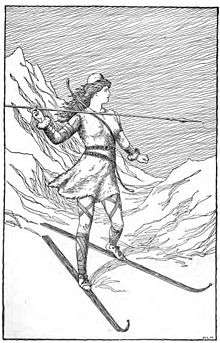

Early skiers used one long pole or spear. The first depiction of a skier with two ski poles dates to 1741.[54] In 1959 Ed Scott introduced the large-diameter, tapered shaft, lightweight aluminum ski pole.[43]

Gallery

.jpg) Knud Bergslien's Birkebeiner escaping with the prince child

Knud Bergslien's Birkebeiner escaping with the prince child Advertisement for ski race in La Porte, California (1869)

Advertisement for ski race in La Porte, California (1869) Theodor von Lerch, an Austrian major, teaching skiing to Japanese army as the first experience to Japan at Jōetsu, Niigata on 12 January 1911.

Theodor von Lerch, an Austrian major, teaching skiing to Japanese army as the first experience to Japan at Jōetsu, Niigata on 12 January 1911. Skiing in Scandinavia, 1767

Skiing in Scandinavia, 1767 The Böksta Runestone is believed to depict the Viking god Ullr with his skis and his bow

The Böksta Runestone is believed to depict the Viking god Ullr with his skis and his bow.jpg) The 1903 rendition of medieval Russian soldiers' use of skis to facilitate their movement during winter campaigns, by Sergey Ivanov.

The 1903 rendition of medieval Russian soldiers' use of skis to facilitate their movement during winter campaigns, by Sergey Ivanov.

Kiandra "Snow Shoe" (Skiing) Carnival, New South Wales, Australia, in 1900.

Kiandra "Snow Shoe" (Skiing) Carnival, New South Wales, Australia, in 1900. Wolf hunting on skis

Wolf hunting on skis Depiction of Samis skiing, by John Bauer.

Depiction of Samis skiing, by John Bauer.

See also

References

- ↑ Editors (December 22, 2010). "Where did skiing come from?". BBC. BBC. Retrieved 2015-01-27.

- ↑ Lund, Morten (Winter 1996). "A Short History of Alpine Skiing". Skiing Heritage. 8 (1). Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- ↑ Merriam-Webster's Dictionary

- ↑ Aasen, Ivar (1950): Ordbog over det norske Folkesprog. Kristiania: Carl C. Werner.

- ↑ Editors (January 25, 2006). "Ancient paintings suggest China invented skiing". China Today. Xinhua News Agency. Retrieved 2015-01-27.

- ↑ Marquand, Edward (March 15, 2006). "Before Scandinavia: These could be the first skiers". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2015-03-08.

- ↑ Burov, Grigori (1985). "Mesolithic wood artefacts from the site of Vis I in the European North-east of the USSR". The Mesolithic in Europe: 392–395.

- ↑ "Bølamannen". Steinkjer Kunnskapsportal. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ↑ http://snl.no/ski/historikk accessed May 25, 2013.

- ↑ Olsen, Jan. "Wiping the snow off Greenland's oldest ski". iol. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ↑ Fant 1300 år gammel ski i Reinheimen, NRK News, published October 6, 2014, accessed October 11, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Saur, Lasse (1999), Norske ski - til glede og besvær, 22 (in Norwegian), Alta: Høgskolen i Finnmark, Avdeling for fritids- og kulturfag, p. 136, ISBN 8279380426

- ↑ Birkely, Hartvig (1994): I Norge har lapperne først indført skierne. Idut.

- ↑ Vaage, Jakob (1955). Milepeler og merkedager gjennom 4000 ar. Ranheim: Norske Skiloperer Ostlandet Nord Oslo. p. 9.

- ↑ Magnus, Olaus. "Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus". Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Bergsland, Einar (1946): På ski. Oslo: Aschehoug.

- ↑ SKI Magazine’s Encyclopedia of Skiing. New York: Harper & Row. 1979. p. 5.

- ↑ de La Tocnaye, Jacques (1801). Promenade d'un Français en Suède et en Norvège. Brunswick: P.F. Fauche et Cie.

- ↑ Ystad, Andreas; Sakshaug, Ingevald (1973). Inderøyboka. Ei bygdebok for Inderøy, Røra og Sandvollan. (in Norwegian). Inderøy, Norway: Inderøy kommune.

- ↑ Vaage, Jakob (1979). Skienes verden (in Norwegian). Oslo: Hjemmets forlag. p. 269. ISBN 9788270061686.

- ↑ Neubauer, Ian Lloyd (August 25, 2011). "The Long Run: Australia's Storied Ski Heaven". Time. Time, Inc. Retrieved 2015-12-27.

- ↑ "Longboards at Mammoth". Mic Mac Publishing. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ↑ "Union Leader - Nansen Ski Jump gets historical marker (seventh paragraph down)". Retrieved December 9, 2011.

- ↑ "History of the Nansen Ski Club". Retrieved December 9, 2011.

- ↑ "Henri Duhamel". bivouak.net. 2013. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ↑ "Chamrousse Ski History". PisteHors.com. 2009. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ↑ Bolitho, Andrea (January 2010). "Top Secret Slopes". France Today. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ↑ "Skis – Bindings – Telemark Turn – Christiania Turn – Slalom". Sondre Norheim - the Skiing Pioneer of Telemark. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ↑ Haarstad, Kjell (1993): Skisportens oppkomst i Norge. Trondheim: Tapir.

- ↑ "About USSA". Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- ↑ Editors (July 6, 1908). "Ski Running at Kiandra—An International Contest". The Argus. Melbourne. p. 8. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- ↑ "Timeline". International Ski Federation. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- ↑ Masia, Seth. "Skis, Trains and Mountains". Skiing Heritage. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ↑ Cárdenas, Fabricio (2014). 66 petites histoires du Pays Catalan [66 Little Stories of Catalan Country] (in French). Perpignan: Ultima Necat. ISBN 978-2-36771-006-8. OCLC 893847466.

- ↑ "The Progression of an Obsession: Ski History 4,000 B.C. - 1930".

- ↑ "The Beginnings of Snowboarding" (PDF). Colorado Ski & Snowboard Museum. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- ↑ Leich, Jeff. "Chronology of Snowmaking" (PDF). New England Ski Museum. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- ↑ "Halvor Kleppen – Telemark Skiing, Norway's Gift to the World", Alpenglow Ski History

- ↑ Allen, E. John B. (2011), Historical Dictionary of Skiing, Historical Dictionaries of Sports, Scarecrow Press, pp. 1–14, ISBN 0810879778

- ↑ Olaus Magnus, 1555:1,4

- ↑ "Västerbotten 1971 nr. 2" magazine in Swedish, includes copious pictures of the ski and the associated equipment.

- 1 2 3 4 Masia, Seth. "Evolution of Ski Shape". Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Fry, John (2006). The story of modern skiing. Hanover: University Press of New England. ISBN 978-1-58465-489-6.

- ↑ Bjertaes, Gunnar. "Patent number: 4005875 Ski construction of the torsion box type". US Patent Office. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ↑ Skiing the wrong way since '95

- ↑ Lert, Wolfgang (March 2002). "A Binding Revolution". Skiing Heritage Journal: 26.

- ↑ "About Us", Rottefella

- ↑ Masia, Seth. "RELEASE! HISTORY OF SAFETY BINDINGS". International Skiing History Association. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ↑ Wolfgang Lert, "A Binding Revolution", Ski Heritage Journal, March 2002, pp. 25-26

- ↑ Kuzmin, Leonid (2006). Investigation of the most essential factors influencing ski glide (PDF) (Licentiate). Luleå University of Technology. Retrieved 2012-10-20.

- ↑ Oberleutnant Hals. Om Skismøring. Vaage: Skienes Verden. p. 254.

- ↑ Masia, Seth (September 2003). "The Wonderful Waxless Ski". Skiing Heritage. 15 (3).

- ↑ Woodward, Bob (January 1985). "Ski wax made (somewhat) simple—Confused by the wax rainbow? Maybe you've gone too far.". Backpacker Magazine. Active Interest Media, Inc.. p. 14. Retrieved 2016-01-16.

- ↑ Hergstrom, P (1748). Beschreibung von dem unter schwedischer Krone gehörigen Lappland. Leipzig: von Rother.

Further reading

- Achard, Michel (2011) La Connaissance du Ski en France Avant 1890: approche bibliographique, 16e-19e siècle Le Bassat: Achard ISBN 9782950411242 [in French]

- Allen, E. John B. (2011). Historical Dictionary of Skiing. Scarecrow Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-8108-6802-1.

- Dresbeck, LeRoy J. (October 1967). "The ski: its history and historiography". Technology and Culture. 8 (4): 467–79 + fig. 1–3. doi:10.2307/3102114. ISSN 0040-165X.

- Huntford, Roland (2008) Two Planks and a Passion: The Dramatic History of Skiing ISBN 978-1441134011

- Allen, E. John B. (2007) The Culture and Sport of Skiing: From Antiquity to World War II Amherst, MA, USA: University of Massachusetts Press, ISBN 9781558496002

- Weinstock, John M. (2003) Skis and Skiing from the Stone Age to the birth of the sport Lewiston, NY: E. Mellen ISBN 9780773467873

- Engen, Alan (1998) For the Love of Skiing: A Visual History ISBN 0879058676

- Lund, Morten (1996) "A Short History of Alpine Skiing" International Skiing History Association

- Lund, Allen, Fry, Masia; et al. (1993). Skiing History Magazine. International Skiing History Association. ISSN 1082-2895.

- Flower, Raymond (1976) The history of skiing and other winter sports Toronto; New York: Methuen Inc. ISBN 0-458-92780-5

- Dudley, Charles M. (1935) 60 Centuries of Skiing Brattleboro, VT, USA: Stephen Daye Press

- Lunn, Arnold (1927) A History of Skiing London: Oxford University Press

External links

![]() Media related to History of skiing at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to History of skiing at Wikimedia Commons