History of geodesy

| Geodesy | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Fundamentals | ||||||||||||||||

| Concepts | ||||||||||||||||

| Technologies | ||||||||||||||||

| Standards | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||

Geodesy (/dʒiːˈɒdɨsi/), also named geodetics, is the scientific discipline that deals with the measurement and representation of the Earth. The history of geodesy began in antiquity and blossomed during the Age of Enlightenment.

Early ideas about the figure of the Earth held the Earth to be flat (see flat earth), and the heavens a physical dome spanning over it. Two early arguments for a spherical Earth were that lunar eclipses were seen as circular shadows which could only be caused by a spherical Earth, and that Polaris is seen lower in the sky as one travels South.

Hellenic world

The early Greeks, in their speculation and theorizing, ranged from the flat disc advocated by Homer to the spherical body postulated by Pythagoras. Pythagoras's idea was supported later by Aristotle.[2] Pythagoras was a mathematician and to him the most perfect figure was a sphere. He reasoned that the gods would create a perfect figure and therefore the Earth was created to be spherical in shape. Anaximenes, an early Greek philosopher, believed strongly that the Earth was rectangular in shape.

Since the spherical shape was the most widely supported during the Greek Era, efforts to determine its size followed. Plato determined the circumference of the Earth (which is slightly over 40,000 km) to be 400,000 stadia (between 62,800 and 74,000 km or 46,250 and 39,250 mi) while Archimedes estimated 300,000 stadia (48,300 km or 30,000 mi), using the Hellenic stadion which scholars generally take to be 185 meters or 1⁄10 of a geographical mile. Plato's figure was a guess and Archimedes' a more conservative approximation.

Hellenistic world

In Egypt, a Greek scholar and philosopher, Eratosthenes (276 BC – 195 BC), is said to have made more explicit measurements. He had heard that on the longest day of the summer solstice, the midday sun shone to the bottom of a well in the town of Syene (Aswan). At the same time, he observed the sun was not directly overhead at Alexandria; instead, it cast a shadow with the vertical equal to 1/50th of a circle (7° 12'). To these observations, Eratosthenes applied certain "known" facts (1) that on the day of the summer solstice, the midday sun was directly over the Tropic of Cancer; (2) Syene was on this tropic; (3) Alexandria and Syene lay on a direct north-south line; (4) The sun was a relatively long way away (astronomical unit). Legend has it that he had someone walk from Alexandria to Syene to measure the distance, which came out to be equal to 5000 stadia or (at the usual Hellenic 185 m per stadion) about 925 km.

From these observations, measurements, and/or "known" facts, Eratosthenes concluded that since the angular deviation of the sun from the vertical direction at Alexandria was also the angle of the subtended arc (see illustration), the linear distance between Alexandria and Syene was 1/50 of the circumference of the Earth which thus must be 50×5000 = 250,000 stadia or probably 25,000 geographical miles. The circumference of the Earth is 24,902 mi (40,075.16 km). Over the poles it is more precisely 40,008 km or 24,860 mi. The actual unit of measure used by Eratosthenes was the stadion. No one knows for sure what his stadion equals in modern units, but some say that it was the Hellenic 185 m stadion.

Had the experiment been carried out as described, it would not be remarkable if it agreed with actuality. What is remarkable is that the result was probably only about 0.4% too high. His measurements were subject to several inaccuracies: (1) though at the summer solstice the noon sun is overhead at the Tropic of Cancer, Syene was not exactly on the tropic (which was at 23° 43' latitude in that day) but about 22 geographical miles to the north; (2) the difference of latitude between Alexandria (31.2 degrees north latitude) and Syene (24.1 degrees) is really 7.1 degrees rather than the perhaps rounded (1/50 of a circle) value of 7° 12' that Eratosthenes used; (3) the actual solstice zenith distance of the noon sun at Alexandria was 31° 12' − 23° 43' = 7° 29' or about 1/48 of a circle not 1/50 = 7° 12', an error closely consistent with use of a vertical gnomon which fixes not the sun's center but the solar upper limb 16' higher; (4) the most importantly flawed element, whether he measured or adopted it, was the latitudinal distance from Alexandria to Syene (or the true Tropic somewhat further south) which he appears to have overestimated by a factor that relates to most of the error in his resulting circumference of the earth.

A parallel later ancient measurement of the size of the earth was made by another Greek scholar, Posidonius. He is said to have noted that the star Canopus was hidden from view in most parts of Greece but that it just grazed the horizon at Rhodes. Posidonius is supposed to have measured the elevation of Canopus at Alexandria and determined that the angle was 1/48 of circle. He assumed the distance from Alexandria to Rhodes to be 5000 stadia, and so he computed the Earth's circumference in stadia as 48 times 5000 = 240,000.[3] Some scholars see these results as luckily semi-accurate due to cancellation of errors. But since the Canopus observations are both mistaken by over a degree, the "experiment" may be not much more than a recycling of Eratosthenes's numbers, while altering 1/50 to the correct 1/48 of a circle. Later, either he or a follower appears to have altered the base distance to agree with Eratosthenes's Alexandria-to-Rhodes figure of 3750 stadia since Posidonius's final circumference was 180,000 stadia, which equals 48×3750 stadia.[4] The 180,000 stadia circumference of Posidonius is suspiciously close to that which results from another method of measuring the earth, by timing ocean sunsets from different heights, a method which is inaccurate due to horizontal atmospheric refraction.

The abovementioned larger and smaller sizes of the earth were those used by Claudius Ptolemy at different times, 252,000 stadia in his Almagest and 180,000 stadia in his later Geography. His midcareer conversion resulted in the latter work's systematic exaggeration of degree longitudes in the Mediterranean by a factor close to the ratio of the two seriously differing sizes discussed here, which indicates [5] that the conventional size of the earth was what changed, not the stadion.

Ancient India

The Indian mathematician Aryabhata (AD 476–550) was a pioneer of mathematical astronomy. He describes the earth as being spherical and that it rotates on its axis, among other things in his work Āryabhaṭīya. Aryabhatiya is divided into four sections. Gitika, Ganitha (mathematics), Kalakriya (reckoning of time) and Gola (celestial sphere). The discovery that the earth rotates on its own axis from west to east is described in Aryabhatiya ( Gitika 3,6; Kalakriya 5; Gola 9,10;).[6] For example, he explained the apparent motion of heavenly bodies is only an illusion (Gola 9), with the following simile;

- Just as a passenger in a boat moving downstream sees the stationary (trees on the river banks) as traversing upstream, so does an observer on earth see the fixed stars as moving towards the west at exactly the same speed (at which the earth moves from west to east.)

Aryabhatiya also estimates the circumference of Earth, with an error of 1%, which is remarkable. Aryabhata gives the radii of the orbits of the planets in terms of the Earth-Sun distance as essentially their periods of rotation around the Sun. He also gave the correct explanation of lunar and solar eclipses and that the Moon shines by reflecting sunlight.[6]

Islamic world

The Muslim scholars, who held to the spherical Earth theory, used it to calculate the distance and direction from any given point on the earth to Mecca. This determined the Qibla, or Muslim direction of prayer. Muslim mathematicians developed spherical trigonometry which was used in these calculations.[7]

Around AD 830 Caliph al-Ma'mun commissioned a group of astronomers led by Al-Khwarizmi to measure the distance from Tadmur (Palmyra) to al-Raqqah, in modern Syria. They found the cities to be separated by one degree of latitude and the distance between them to be 66 2⁄3 miles and thus calculated the Earth's circumference to be 24,000 miles.[8] Another estimate given was 56 2⁄3 Arabic miles per degree, which corresponds to 111.8 km per degree and a circumference of 40,248 km, very close to the currently modern values of 111.3 km per degree and 40,068 km circumference, respectively.[9]

Muslim astronomers and geographers were aware of magnetic declination by the 15th century, when the Egyptian astronomer 'Abd al-'Aziz al-Wafa'i (d. 1469/1471) measured it as 7 degrees from Cairo.[10]

Al-Biruni

Of the medieval Persian Abu Rayhan al-Biruni (973–1048) it is said:

"Important contributions to geodesy and geography were also made by Biruni. He introduced techniques to measure the earth and distances on it using triangulation. He found the radius of the earth to be 6339.6 km, a value not obtained in the West until the 16th century. His Masudic canon contains a table giving the coordinates of six hundred places, almost all of which he had direct knowledge."[11]

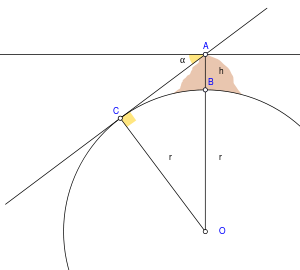

At the age of 17, Al-Biruni calculated the latitude of Kath, Khwarazm, using the maximum altitude of the Sun. Al-Biruni also solved a complex geodesic equation in order to accurately compute the Earth's circumference, which were close to modern values of the Earth's circumference.[12][13] His estimate of 6,339.9 km for the Earth radius was only 16.8 km less than the modern value of 6,356.7523142 km (WGS84 polar radius "b"). In contrast to his predecessors who measured the Earth's circumference by sighting the Sun simultaneously from two different locations, Al-Biruni developed a new method of using trigonometric calculations based on the angle between a plain and mountain top which yielded more accurate measurements of the Earth's circumference and made it possible for it to be measured by a single person from a single location.[14][15][16] Al-Biruni's method's motivation was to avoid "walking across hot, dusty deserts" and the idea came to him when he was on top of a tall mountain in India (present day Pind Dadan Khan, Pakistan).[16] From the top of the mountain, he sighted the dip angle which, along with the mountain's height (which he calculated beforehand), he applied to the law of sines formula. This was the earliest known use of dip angle and the earliest practical use of the law of sines.[15][16] He also made use of algebra to formulate trigonometric equations and used the astrolabe to measure angles.[17] His method can be summarized as follows:

He first calculated the height of the mountain by going to two points at sea level with a known distance apart and then measuring the angle between the plain and the top of the mountain for both points. He made both the measurements using an astrolabe. He then used the following trigonometric formula relating the distance (d) between both points with the tangents of their angles (θ) to determine the height (h) of the mountain:[18]

He then stood at the highest point of the mountain, where he measured the dip angle using an astrolabe.[18] He applied the values he obtained for the dip angle and the mountain's height to the following trigonometric formula in order to calculate the Earth's radius:[18]

where[18]

- R = Earth radius

- h = height of mountain

- θ = dip angle

Al-Biruni had also, by the age of 22, written a study of map projections, Cartography, which included a method for projecting a hemisphere on a plane. Around 1025, Al-Biruni was the first to describe a polar equi-azimuthal equidistant projection of the celestial sphere.[19] He was also regarded as the most skilled when it came to mapping cities and measuring the distances between them, which he did for many cities in the Middle East and western Indian subcontinent. He often combined astronomical readings and mathematical equations, in order to develop methods of pin-pointing locations by recording degrees of latitude and longitude. He also developed similar techniques when it came to measuring the heights of mountains, depths of valleys, and expanse of the horizon, in The Chronology of the Ancient Nations. He also discussed human geography and the planetary habitability of the Earth. He hypothesized that roughly a quarter of the Earth's surface is habitable by humans, and also argued that the shores of Asia and Europe were "separated by a vast sea, too dark and dense to navigate and too risky to try".

Medieval Europe

Revising the figures attributed to Posidonius, another Greek philosopher determined 18,000 miles as the Earth's circumference. This last figure was promulgated by Ptolemy through his world maps. The maps of Ptolemy strongly influenced the cartographers of the Middle Ages. It is probable that Christopher Columbus, using such maps, was led to believe that Asia was only 3 or 4 thousand miles west of Europe.

Ptolemy's view was not universal, however, and chapter 20 of Mandeville's Travels (c. 1357) supports Eratosthenes' calculation.

It was not until the 16th century that his concept of the Earth's size was revised. During that period the Flemish cartographer, Mercator, made successive reductions in the size of the Mediterranean Sea and all of Europe which had the effect of increasing the size of the earth.

Early modern period

The invention of the telescope and the theodolite and the development of logarithm tables allowed exact triangulation and grade measurement.

Europe

In 1505 the cosmographer and explorer Duarte Pacheco Pereira calculated the value of the degree of the meridian arc with a margin of error of only 4%, when the current error at the time varied between 7 and 15%.[20]

Jean Picard performed the first modern meridian arc measurement in 1669–1670. He measured a baseline using wooden rods, a telescope (for his angular measurements), and logarithms (for computation). Jacques Cassini later continued Picard's arc northward to Dunkirk and southward to the Spanish border. Cassini divided the measured arc into two parts, one northward from Paris, another southward. When he computed the length of a degree from both chains, he found that the length of one degree of longitude in the northern part of the chain was shorter than that in the southern part (see illustration).

This result, if correct, meant that the earth was not a sphere, but a prolate spheroid (taller than wide). However, this contradicted computations by Isaac Newton and Christiaan Huygens. Newton's theory of gravitation predicted the Earth to be an oblate spheroid (wider than tall), with a flattening of 1:230.

The issue could be settled by measuring, for a number of points on earth, the relationship between their distance (in north-south direction) and the angles between their zeniths. On an oblate Earth, the meridional distance corresponding to one degree of longitude will grow toward the poles, as can be demonstrated mathematically.

The French Academy of Sciences dispatched two expeditions. One expedition (1736–37) under Pierre Louis Maupertuis was sent to Torne Valley (near the Earth's northern pole). The second mission (1735–44) under Pierre Bouguer was sent to what is modern-day Ecuador, near the equator. Their measurements demonstrated an oblate Earth, with a flattening of 1:210. This approximation to the true shape of the Earth became the new reference ellipsoid.

Asia and Americas

In South America Bouguer noticed, as did George Everest in the 19th century Great Trigonometric Survey of India, that the astronomical vertical tended to be pulled in the direction of large mountain ranges, due to the gravitational attraction of these huge piles of rock. As this vertical is everywhere perpendicular to the idealized surface of mean sea level, or the geoid, this means that the figure of the Earth is even more irregular than an ellipsoid of revolution. Thus the study of the "undulation of the geoid" became the next great undertaking in the science of studying the figure of the Earth.

19th century

In the late 19th century the Zentralbüro für die Internationale Erdmessung (Central Bureau for International Geodesy) was established by Austria-Hungary and Germany. One of its most important goals was the derivation of an international ellipsoid and a gravity formula which should be optimal not only for Europe but also for the whole world. The Zentralbüro was an early predecessor of the International Association of Geodesy (IAG) and the International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics (IUGG) which was founded in 1919.

Most of the relevant theories were derived by the German geodesist Friedrich Robert Helmert in his famous books Die mathematischen und physikalischen Theorieen der höheren Geodäsie, Einleitung und 1. Teil (1880) and 2. Teil (1884); English translation: Mathematical and Physical Theories of Higher Geodesy, Vol. 1 and Vol. 2. Helmert also derived the first global ellipsoid in 1906 with an accuracy of 100 meters (0.002 percent of the Earth's radii). The US geodesist Hayford derived a global ellipsoid in ~1910, based on intercontinental isostasy and an accuracy of 200 m. It was adopted by the IUGG as "international ellipsoid 1924".

See also

Notes

- ↑ NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center (3 February 2012). Looking Down a Well: A Brief History of Geodesy (digital animation). NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center. Goddard Multimedia Animation Number: 10910. Archived from the original (OGV) on 3 February 2012. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ↑ Aristotle On the Heavens, Book II 298 B

- ↑ Cleomedes 1.10

- ↑ Strabo 2.2.2, 2.5.24; D.Rawlins, Contributions

- ↑ D.Rawlins (2007). "Investigations of the Geographical Directory 1979–2007 "; DIO, volume 6, number 1, page 11, note 47, 1996.

- 1 2 http://www.ias.ac.in/resonance/march2006/p51-68.pdf

- ↑ David A. King, Astronomy in the Service of Islam, (Aldershot (U.K.): Variorum), 1993.

- ↑ Gharā'ib al-funūn wa-mulah al-`uyūn (The Book of Curiosities of the Sciences and Marvels for the Eyes), 2.1 "On the mensuration of the Earth and its division into seven climes, as related by Ptolemy and others," (ff. 22b–23a)

- ↑ Edward S. Kennedy, Mathematical Geography, pp. 187–8, in (Rashed & Morelon 1996, pp. 185–201)

- ↑ Barmore, Frank E. (April 1985), "Turkish Mosque Orientation and the Secular Variation of the Magnetic Declination", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, University of Chicago Press, 44 (2): 81–98 [98], doi:10.1086/373112

- ↑ John J. O'Connor, Edmund F. Robertson (1999). Abu Arrayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni, MacTutor History of Mathematics archive.

- ↑ "Khwarizm". Foundation for Science Technology and Civilisation. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ↑ James S. Aber (2003). Alberuni calculated the Earth's circumference at a small town of Pind Dadan Khan, District Jhelum, Punjab, Pakistan.Abu Rayhan al-Biruni, Emporia State University.

- ↑ Lenn Evan Goodman (1992), Avicenna, p. 31, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-01929-X.

- 1 2 Behnaz Savizi (2007), "Applicable Problems in History of Mathematics: Practical Examples for the Classroom", Teaching Mathematics and Its Applications, Oxford University Press, 26 (1): 45–50, doi:10.1093/teamat/hrl009 (cf. Behnaz Savizi. "Applicable Problems in History of Mathematics; Practical Examples for the Classroom". University of Exeter. Retrieved 2010-02-21.)

- 1 2 3 Beatrice Lumpkin (1997), Geometry Activities from Many Cultures, Walch Publishing, pp. 60 & 112–3, ISBN 0-8251-3285-1

- ↑ Jim Al-Khalili, The Empire of Reason 2/6 (Science and Islam – Episode 2 of 3) on YouTube, BBC

- 1 2 3 4 Jim Al-Khalili, The Empire of Reason 3/6 (Science and Islam – Episode 2 of 3) on YouTube, BBC

- ↑ David A. King (1996), "Astronomy and Islamic society: Qibla, gnomics and timekeeping", in Roshdi Rashed, ed., Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science, Vol. 1, p. 128–184 [153]. Routledge, London and New York.

- ↑ Universidade de São Paulo, Departamento de História, Sociedade de Estudos Históricos (Brazil), Revista de História (1965), ed. 61-64, p. 350

References

- An early version of this article was taken from the public domain source at http://www.ngs.noaa.gov/PUBS_LIB/Geodesy4Layman/TR80003A.HTM#ZZ4.

- J. L. Greenberg: The problem of the Earth's shape from Newton to Clairaut: the rise of mathematical science in eighteenth-century Paris and the fall of "normal" science. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 1995 ISBN 0-521-38541-5

- M .R. Hoare: Quest for the true figure of the Earth: ideas and expeditions in four centuries of geodesy. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2004 ISBN 0-7546-5020-0

- D. Rawlins: "Ancient Geodesy: Achievement and Corruption" 1984 (Greenwich Meridian Centenary, published in Vistas in Astronomy, v.28, 255–268, 1985)

- D. Rawlins: "Methods for Measuring the Earth's Size by Determining the Curvature of the Sea" and "Racking the Stade for Eratosthenes", appendices to "The Eratosthenes–Strabo Nile Map. Is It the Earliest Surviving Instance of Spherical Cartography? Did It Supply the 5000 Stades Arc for Eratosthenes' Experiment?", Archive for History of Exact Sciences, v.26, 211–219, 1982

- C. Taisbak: "Posidonius vindicated at all costs? Modern scholarship versus the stoic earth measurer". Centaurus v.18, 253–269, 1974