History of childhood

The history of childhood has been a topic of interest in social history since the highly influential book Centuries of Childhood, published by French historian Philippe Ariès in 1960. He argued that "childhood" is a concept created by modern society. Ariès studied paintings, gravestones, furniture, and school records and found that before the 17th-century, children were represented as mini-adults.

Other scholars have emphasized that medieval and early modern child rearing was not indifferent, negligent, and brutal. Stressing the context of pre-industrial poverty and high infant mortality (with a third or more of the babies dying), actual child-rearing practices represented appropriate behavior in the circumstances. He points to extensive parental care during sickness, and to grief at death, sacrifices by parents to maximize child welfare, and a wide cult of childhood in religious practice.[1]

Preindustrial and medieval

Historians had assumed that traditional families in the preindustrial era involved the extended family, with grandparent, parents, children and perhaps some other relatives all living together and ruled by an elderly patriarch. There were examples of this in the Balkans—and in aristocratic families. However, the typical pattern in Western Europe was the much simpler nuclear family of husband, wife and their children (and perhaps a servant, who might well be a relative). Children were often temporarily sent off as servants to relatives in need of help.[2]

In medieval Europe there was a model of distinct stages of life, which demarcated when childhood began and ended. A new baby was a notable event. Nobles immediately started thinking of a marriage arrangement that would benefit the family. Birthdays were not major events as the children celebrated their saints' day after whom they were named. Church law and common law regarded children as equal to adults for some purposes and distinct for other purposes.[3]

Education in the sense of training was the exclusive function of families for the vast majority of children until the 19th century. In the Middle Ages the major cathedrals operated education programs for small numbers of teenage boys designed to produce priests. Universities started to appear to train physicians, lawyers, and government officials, and (mostly) priests. The first universities appeared around 1100; - the University of Bologna in 1088, the University of Paris in 1150 and the Oxford in 1167. Students entered as young as 13 and stayed for 6 to 12 years.[4]

Early modern periods

In England in the Elizabethan era, the transmission of social norms was a family matter and children were taught the basic etiquette of proper manners and respecting others.[5] Some boys attended grammar school, usually taught by the local priest.[6]

During the 1600s, a shift in philosophical and social attitudes toward children and the notion of 'childhood' began in Europe.[7] Adults increasingly saw children as separate beings, innocent and in need of protection and training by the adults around them. The English philosopher John Locke was particularly influential in defining this new attitude towards children, especially with regard to his theory of the tabula rasa, promulgated in his 1690 An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. In Locke's philosophy, tabula rasa was the theory that the (human) mind is at birth a "blank slate" without rules for processing data, and that data is added and rules for processing are formed solely by one's sensory experiences. A corollary of this doctrine was that the mind of the child was born blank, and that it was the duty of the parents to imbue the child with correct notions. Locke himself emphasised the importance of providing children with "easy pleasant books" to develop their minds rather than using force to compel them; "children may be cozened into a knowledge of the letters; be taught to read, without perceiving it to be anything but a sport, and play themselves into that which others are whipped for."

During the early period of capitalism, the rise of a large, commercial middle class, mainly in the Protestant countries of Holland and England, brought about a new family ideology centred around the upbringing of children. Puritanism stressed the importance of individual salvation and concern for the spiritual welfare of children. It became widely recognized that children possess rights on their own behalf. This included the rights of poor children to sustenance, membership in a community, education, and job training. The Poor Relief Acts in Elizabethan England put responsibility on each Parish to care for all the poor children in the area.[8]

Enlightenment era

The modern notion of childhood with its own autonomy and goals began to emerge during the Enlightenment and the Romantic period that followed it. Jean Jacques Rousseau formulated the romantic attitude towards children in his famous 1762 novel Emile: or, On Education. Building on the ideas of John Locke and other 17th-century thinkers, Rousseau described childhood as a brief period of sanctuary before people encounter the perils and hardships of adulthood. "Why rob these innocents of the joys which pass so quickly," Rousseau pleaded. "Why fill with bitterness the fleeting early days of childhood, days which will no more return for them than for you?"[9]

These new attitudes can be discerned from the dramatic increase in artistic depictions of children at the time. Instead of depicting children as small versions of adults typically engaged in 'adult' tasks, they were increasingly shown as physically and emotionally distinct and were often used as an allegory for innocence. Sir Joshua Reynolds' extensive children portraiture clearly demonstrate the new enlightened attitudes toward young children. His 1788 painting The Age of Innocence, emphasizes the innocence and natural grace of the posing child and soon became a public favourite.

Building on Locke's theory that all minds began as a blank slate, the eighteenth century witnessed a marked rise in children's textbooks that were more easy to read, and in publications like poems, stories, novellas and games that were aimed at the impressionable minds of young learners. These books promoted reading, writing and drawing as central forms of self-formation for children.[10]

During this period children's education became more common and institutionalized, in order to supply the church and state with the functionaries to serve as their future administrators. Small local schools where poor children learned to read and write were established by philanthropists, while the sons and daughters of the noble and bourgeois elites were given distinct educations at the grammar school and university.[11]

Children's rights under the law

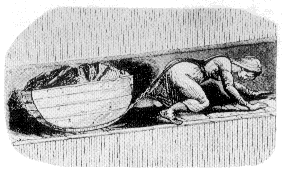

With the onset of industrialisation in England, a growing divergence between high-minded romantic ideals of childhood and the reality of the growing magnitude of child exploitation in the workplace, became increasingly apparent. Although child labour was common in pre-industrial times, children would generally help their parents with the farming or cottage crafts. By the late 18th century, however, children were specially employed at the factories and mines and as chimney sweeps,[12] often working long hours in dangerous jobs for low pay.[13] In England and Scotland in 1788, two-thirds of the workers in 143 water-powered cotton mills were described as children.[14] In 19th-century Great Britain, one-third of poor families were without a breadwinner, as a result of death or abandonment, obliging many children to work from a young age.

As the century wore on, the contradiction between the conditions on the ground for children of the poor and the middle-class notion of childhood as a time of innocence led to the first campaigns for the imposition of legal protection for children. Reformers attacked child labor from the 1830s onward, bolstered by the horrific descriptions of London street life by Charles Dickens.[16] The campaign that led to the Factory Acts was spearheaded by rich philanthropists of the era, especially Lord Shaftesbury, who introduced Bills in Parliament to mitigate the exploitation of children at the workplace. In 1833 he introduced the Ten Hours Act 1833 into the Commons, which provided that children working in the cotton and woollen industries must be aged nine or above; no person under the age of eighteen was to work more than ten hours a day or eight hours on a Saturday; and no one under twenty-five was to work nights.[17] Legal interventions throughout the century increased the level of childhood protection, despite the prevalence of the Victorian laissez-faire attitude toward government interference. In 1856, the law permitted child labour past age 9 for 60 hours per week. In 1901, the permissible child labour age was raised to 12.[18][19]

Modern childhood

The modern attitude to children emerged by the late 19th century; the Victorian middle and upper classes emphasized the role of the family and the sanctity of the child, - an attitude that has remained dominant in Western societies ever since.[20] This can be seen in the emergence of the new genre of children's literature. Instead of the didactic nature of children's books of a previous age, authors began to write humorous, child-oriented books, more attuned to the child's imagination. Tom Brown's School Days by Thomas Hughes appeared in 1857, and is considered as the founding book in the school story tradition.[21] Lewis Carroll's fantasy Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, published in 1865 in England, signalled the change in writing style for children to an imaginative and empathetic one. Regarded as the first "English masterpiece written for children" and as a founding book in the development of fantasy literature, its publication opened the "First Golden Age" of children's literature in Britain and Europe that continued until the early 1900s.[21]

The latter half of the century also saw the introduction of compulsory state schooling of children across Europe, which decisively removed children from the workplace into schools. Modern methods of public schooling, with tax-supported schools, compulsory attendance, and educated teachers emerged first in Prussia in the early 19th century,[22] and was adopted by Britain, the United States, France[23] and other modern nations by 1900.

The market economy of the 19th century enabled the concept of childhood as a time of fun of happiness. Factory-made dolls and doll houses delighted the girls and organized sports and activities were played by the boys.[24] The Boy Scouts was founded by Sir Robert Baden-Powell in 1908,[25] which provided young boys with outdoor activities aiming at developing character, citizenship, and personal fitness qualities.[26]

The nature of childhood on the American frontier is disputed. One group of scholars, following the lead of novelists Willa Cather and Laura Ingalls Wilder, argue that the rural environment was salubrious. Historians Katherine Harris[27] and Elliott West[28] write that rural upbringing allowed children to break loose from urban hierarchies of age and gender, promoted family interdependence, and in the end produced children who were more self-reliant, mobile, adaptable, responsible, independent and more in touch with nature than their urban or eastern counterparts. On the other hand, historians Elizabeth Hampsten[29] and Lillian Schlissel[30] offer a grim portrait of loneliness, privation, abuse, and demanding physical labor from an early age. Riney-Kehrberg takes a middle position.[31] Over the 21st century, some sex-selection clinics have shown a preference for female children over male children.[32]

Non-Western world

The modern concept of childhood was copied by non-Western societies as they modernized. In the vanguard was Japan, which actively began to engage with the West after 1860. Meiji era leaders decided that the nation-state had the primary role in mobilizing individuals - and children - in service of the state. The Western-style school was introduced as the agent to reach that goal. By the 1890s, schools were generating new sensibilities regarding childhood.[33] By the turn of the 20th century, Japan had numerous reformers, child experts, magazine editors and well-educated mothers who had adopted these new attitudes.[34][35]

See also

- Annales School

- Childhood

- History of education

- History of education in the United States

- Social history

Notes

- ↑ Stephen Wilson, "The myth of motherhood a myth: the historical view of European child-rearing," Social History, May 1984, Vol. 9 Issue 2, pp 181-198

- ↑ King, "Concepts of Childhood: What We Know and Where We Might Go," Renaissance Quarterly (2007)

- ↑ Nicholas Orme, Medieval Children (2003)

- ↑ Olaf Pedersen, The First Universities (1997).

- ↑ Pearson, Lee E. (1957). "Education of children". Elizabethans at home. Stanford University Press. pp. 140–41. ISBN 0-8047-0494-5.

- ↑ Simon, Joan (1966). Education and Society in Tudor England. London: Cambridge University Press. p. 373. ISBN 978-0-521-22854-1.

- ↑ Carol K. Sigelman, Elizabeth A. Rider (2008). Life-Span Human Development. Cengage Learning. p. 8.

- ↑ Vivian C. Fox, "Poor Children's Rights in Early Modern England," Journal of Psychohistory, Jan 1996, Vol. 23 Issue 3, pp 286-306

- ↑ David Cohen, The development of play (2006) p 20

- ↑ Eddy, Matthew Daniel (2010). "The Alphabets of Nature: Children, Books and Natural History, 1750-1800',". Nuncius. 23: 1–22.

- ↑ Carolyn C. Lougee, "'Noblesse,' Domesticity, and Social Reform: The Education of Girls by Fenelon and Saint-Cyr", History of Education Quarterly 1974 14(1): 87–113

- ↑ Laura Del Col, West Virginia University, The Life of the Industrial Worker in Nineteenth-Century England

- ↑ Barbara Daniels, Poverty and Families in the Victorian Era

- ↑ "Child Labour and the Division of Labour in the Early English Cotton Mills". Douglas A. Galbi. Centre for History and Economics, King's College, Cambridge CB2 1ST.

- ↑ Jane Humphries, Childhood And Child Labour in the British Industrial Revolution (2010) p 33

- ↑ Amberyl Malkovich, Charles Dickens and the Victorian Child: Romanticizing and Socializing the Imperfect Child (2011)

- ↑ Battiscombe, p. 88, p. 91.

- ↑ "The Life of the Industrial Worker in Nineteenth-Century England". Laura Del Col, West Virginia University.

- ↑ The Factory and Workshop Act 1901

- ↑ Thomas E. Jordan, Victorian Child Savers and Their Culture: A Thematic Evaluation (1998)

- 1 2 Knowles, Murray (1996). Language and Control in Children's Literature. Psychology Press.

- ↑ Eda Sagarra, A Social History of Germany 1648-1914 (1977) pp 275-84

- ↑ Eugen Weber, Peasants into Frenchmen: The Modernization of Rural France, 1870-1914 (1976) pp 303-38

- ↑ Howard Chudacoff, Children at Play: An American History (2008)

- ↑ Woolgar, Brian; La Riviere, Sheila (2002). Why Brownsea? The Beginnings of Scouting. Brownsea Island Scout and Guide Management Committee.

- ↑ Boehmer, Elleke (2004). Notes to 2004 edition of Scouting for Boys. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Katherine Harris, Long Vistas: Women and Families on Colorado Homesteads (1993)

- ↑ Elliott West, Growing Up with the Country: Childhood on the Far Western Frontier (1989)

- ↑ Elizabeth Hampsten, Settlers' Children: Growing Up on the Great Plains (1991)

- ↑ Lillian Schlissel, Byrd Gibbens and Elizabeth Hampsten, Far from Home: Families of the Westward Journey (2002)

- ↑ Pamela Riney-Kehrberg, Childhood on the Farm: Work, Play, and Coming of Age in the Midwest (2005)

- ↑ http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2010/07/the-end-of-men/308135/

- ↑ Brian Platt, "Japanese Childhood, Modern Childhood: The Nation-State, the School, and 19th-Century Globalization," Journal of Social History, Summer 2005, Vol. 38 Issue 4, pp 965-985

- ↑ Kathleen S. Uno, Passages to Modernity: Motherhood, Childhood, and Social Reform in Early Twentieth Century Japan (1999)

- ↑ Mark Jones, Children as Treasures: Childhood and the Middle Class in Early Twentieth Century Japan (2010)

Bibliography

- Cunningham, Hugh. Children and Childhood in Western Society since 1500. (1995); strongest on Britain

- deMause, Lloyde, ed. The History of Childhood. (1976), psychohistory.

- Hawes, Joseph and N. Ray Hiner, eds. Children in Historical and Comparative Perspective (1991), articles by scholars

- Heywood, Colin. A History of Childhood (2001), from medieval to 20th century; strongest on France

- Pollock, Linda A. Forgotten Children: Parent-child relations from 1500 to 1900 (1983).

- Sommerville, John. The Rise and Fall of Childhood (1982), from antiquity to the present

Literature & ideas

- Bunge, Marcia J., ed. The Child in Christian Thought. (2001)

- O’Malley, Andrew. The Making of the Modern Child: Children’s Literature and Childhood in the Late Eighteenth Century. (2003).

- Zornado, Joseph L. Inventing the Child: Culture, Ideology, and the Story of Childhood. (2001), covers Shakespeare, Brothers Grimm, Freud, Walt Disney, etc.

Britain

- Cunnington, Phillis and Anne Buck. Children’s Costume in England: 1300 to 1900 (1965)

- Battiscombe, Georgina. Shaftesbury: A Biography of the Seventh Earl. 1801–1885 (1974)

- Hanawalt, Barbara. Growing Up in Medieval London: The Experience of Childhood in History (1995)

- Lavalette; Michael. A Thing of the Past? Child Labour in Britain in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries (1999) online edition

- Olsen, Stephanie. Juvenile Nation: Youth, Emotions and the Making of the Modern British Citizen. (2014)

- Pinchbeck, Ivy and Margaret Hewitt. Children in English Society. (2 vols. 1969); covers 1500 to 1948

- Sommerville, C. John. The Discovery of Childhood in Puritan England. (1992).

- Stone, Lawrence. The Family, Sex and Marriage in England 1500-1800 (1979).

- Welshman, John. Churchill's Children: The Evacuee Experience in Wartime Britain (2010)

Europe

- Ariès, Philippe. Centuries of Childhood: A Social History of Family Life. (1962). Influential study on France that helped launch the field

- Immel, Andrea and Michael Witmore, eds. Childhood and Children’s Books in Early Modern Europe, 1550-1800. (2006).

- Kopf, Hedda Rosner. Understanding Anne Frank's the Diary of a Young Girl: A Student Casebook to Issues, Sources, and Historical Documents (1997) online edition

- Krupp, Anthony. Reason's Children: Childhood in Early Modern Philosophy (2009)

- Nicholas, Lynn H. Cruel World: The Children of Europe in the Nazi Web (2005) 656pp

- Orme, Nicholas. Medieval Children (2003)

- Rawson, Beryl. Children and Childhood in Roman Italy (2003).

- Schultz, James. The Knowledge of Childhood in the German Middle Ages.

- Zahra, Tara. "Lost Children: Displacement, Family, and Nation in Postwar Europe," Journal of Modern History, March 2009, Vol. 81 Issue 1, pp 45–86, covers 1945 to 1951 in JSTOR

United States

- Bernstein, Robin. Racial Innocence: Performing American Childhood from Slavery to Civil Rights (2011) online edition

- Block, James E. The Crucible of Consent: American Child Rearing and the Forging of Liberal Society (2012) excerpt and text search

- Chudacoff, Howard. Children at Play: An American History (2008).

- Del Mar, David Peterson. The American Family: From Obligation to Freedom (Palgrave Macmillan; 2012) 211 pages; the American family over four centuries.

- Fass, Paula. The End of American Childhood: A History of Parenting from Life on the Frontier to the Managed Child (2016) excerpt

- Fass, Paula, and Mary Ann Mason, eds. Childhood in America (2000), 725pp; short excerpts from 178 primary and secondary sources

- Fass, Paula and Michael Grossberg, eds. Reinventing Childhood After World War II (University of Pennsylvania Press; 2012) 182 pages; scholarly esays on major changes in the experiences of children in Western societies, with a focus on the U.S.

- Fieldston, Sara. Raising the World: Child Welfare in the American Century (Harvard University Press, 2015) 316 pp.

- Graff, Harvey J. Conflicting Paths: Growing Up in America (1997), a theoretical approach that uses a great deal of material from children

- Hiner, N. Ray Hiner, and Joseph M. Hawes, eds. Growing Up in America: Children in Historical Perspective (1985), essays by leading historians

- Holt, Marilyn Irvin. Cold War Kids: Politics and Childhood in Postwar America, 1945-1960 (University Press of Kansas; 2014) 224 pages; emphasis on the growing role of politics and federal policy

- Illick, Joseph E. American Childhoods (2002).

- Klapper, Melissa R. Small Strangers: The Experiences of Immigrant Children in America, 1880-1925 (2007) excerpt

- Marten, James, ed. Children and Youth during the Civil War Era (2012) excerpt and text search

- Marten, James. Children and Youth in a New Nation (2009)

- Marten, James. Childhood and Child Welfare in the Progressive Era: A Brief History with Documents (2004), includes primary sources

- Marten, James. The Children's Civil War (2000) excerpt and text search

- Mintz, Steven. Huck's Raft: A History of American Childhood (2004) online edition

- Riney-Kehrberg, Pamela. Childhood on the Farm: Work, Play, and Coming of Age in the Midwest (2005) 300 pp.

- Riney-Kehrberg, Pamela. The Nature of Childhood: An Environmental History of Growing Up in America since 1865 (2014) excerpt and text search

- Tuttle, Jr. William M. Daddy's Gone to War: The Second World War in the Lives of America's Children (1995) online edition

- West, Elliott, and Paula Petrik, eds. Small Worlds: Children and Adolescents in America, 1850-1950 (1992)

- Zelizer, Viviana A. Pricing the Priceless Child: The Changing Social Value of Children (1994) Emphasis on use of life insurance policies. excerpt

Primary sources

- Bremner, Robert H. et al. eds. Children and Youth in America, Volume I: 1600-1865 (1970); Children and Youth in America: A Documentary History, Vol. 2: 1866-1932 (2 vol 1971); Children and Youth in America: A Documentary History, Vol. 3: 1933-1973 (2 vol. 1974). 5 volume set

Latin America

- González, Ondina E. and Bianca Premo. Raising an Empire: Children in Early Modern Iberia & Colonial Latin America (2007) 258p; covers 1500-1800 with essays by historians on orphans and related topics

- Rodríguez Jiménez, Pablo and María Emma Manarelli (coord.). Historia de la infancia en América Latina, Universidad Externado de Colombia, Bogotá (2007).

- Rojas Flores, Jorge. Historia de la infancia en el Chile republicano, 1810-2010, Ocho Libros, Santiago (2010), 830p. online access, full

Asia

- Bai, Limin. "Children as the Youthful Hope of an Old Empire: Race, Nationalism, and Elementary Education in China, 1895-1915," Journal of the History of Childhood & Youth, March 2008, Vol. 1 Issue 2, pp 210–231

- Cross, Gary and Gregory Smits.. "Japan, the U.S. and the Globalization of Children's Consumer Culture," Journal of Social History, Summer 2005, Vol. 38 Issue 4, pp 873–890

- Ellis, Catriona. "Education for All: Reassessing the Historiography of Education in Colonial India," History Compass, March 2009, Vol. 7 Issue 2, pp 363–375

- Hsiung, Ping-chen. Tender Voyage: Children & Childhood in Late Imperial China (2005) 351pp

- Jones, Mark A. Children as Treasures: Childhood and the Middle Class in Early 20th Century Japan (2010), covers 1890 to 1930

- Platt, Brian. Burning and Building: Schooling and State Formation in Japan, 1750-1890 (2004)

- Raddock, David M. "Growing Up in New China: A Twist in the Circle of Filial Piety," History of Childhood Quarterly, 1974, Vol. 2 Issue 2, pp 201–220

- Saari, Jon L. Legacies of Childhood: Growing Up Chinese in a Time of Crisis, 1890-1920 (1990) 379pp

- Walsh, Judith E.. Growing Up in British India: Indian Autobiographers on Childhood & Education under the Raj (1983) 178pp

- Weiner, Myron. Child and the State in India (1991) 213 pp; covers 1947 to 1991

Canada

- Sutherland, Neil. , Children in English-Canadian Society: Framing the Twentieth-Century Consensus (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1976, reprinted 1978).

- Sutherland, Neil. Growing Up: Childhood in English Canada From the Great War to the Age of Television (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997).

- Comacchio, Cynthia. 'Nations are Built of Babies': Saving Ontario's Mothers and Children, 1900 to 1940 (Montreal and Kingston McGill-Queen's University Press, 1993).

- Comacchio, Cynthia. The Dominion of Youth: Adolescence and the Making of a Modern Canada, 1920 to 1950 (Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2006).

- Myers, Tamara. Caught: Montreal's Modern Girls and the Law (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2006).

- Brookfield, Tarah. Cold War Comforts: Canadian Women, Child Safety, and Global Insecurity (Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2012).

- Gleason, Mona. Normalizing the Ideal: Psychology, Schooling and the Family in Postwar Canada. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1996).

- Gleason, Mona. Small Matters: Canadian Children in Sickness and Health, 1900 to 1940. (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2013).

- Axelrod, Paul. The Promise of Schooling: Education in Canada, 1800 to 1914. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997)

Global

- Olsen, Stephanie, ed. Childhood, Youth and Emotions in Modern History: National, Colonial and Global Perspectives. (2015)

Child labour

- "Child Employing Industries," Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science Vol. 35, Mar., 1910 in JSTOR, 32 essays by American experts in 1910

- Goldberg, Ellis. Trade, Reputation, and Child Labor in Twentieth-Century Egypt (2004) excerpt and text search ]

- Grier, Beverly. Invisible Hands: Child Labor and the State in Colonial Zimbabwe (2005)

- Hindman, Hugh D. Child Labor: An American History (2002)

- Humphries, Jane. Childhood and Child Labour in the British Industrial Revolution (Cambridge Studies in Economic History) (2011) excerpt and text search

- Kirby, Peter. Child Labour in Britain, 1750-1870 (2003) excerpt and text search

- Mofford, Juliet. Child Labor in America (1970)

- Tuttle, Carolyn. Hard At Work In Factories And Mines: The Economics Of Child Labor During The British Industrial Revolution (1999)

Historiography

- Cunningham, Hugh. "Histories of Childhood," American Historical Review, Oct 1998, Vol. 103 Issue 4, pp 1195–1208 in JSTOR

- Fass, Paula. "The World is at our Door: Why Historians of Children and Childhood Should Open Up," Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth, Jan 2008, Vol. 1 Issue 1, pp 11–31 on U.S.

- Hawes, Joseph M. and N. Ray Hiner, "Hidden in Plain View: The History of Children (and Childhood) in the Twenty-First Century," Journal of the History of Childhood & Youth, Jan 2008, Vol. 1 Issue 1, pp 43–49; on U.S.

- Hsiung, Ping-chen. "Treading a Different Path? Thoughts on Childhood Studies in Chinese History," Journal of the History of Childhood & Youth, Jan 2008, Vol. 1 Issue 1, pp 77–85

- King, Margaret L. "Concepts of Childhood: What We Know and Where We Might Go," Renaissance Quarterly Volume: 60. Issue: 2. 2007. pp 371+. online edition

- Premo, Bianca. "How Latin America's History of Childhood Came of Age," Journal of the History of Childhood & Youth, Jan 2008, Vol. 1 Issue 1, pp 63–76

- Stearns, Peter N. "Challenges in the History of Childhood," Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth, Jan 2008, Vol. 1 Issue 1, pp 35–42

- Stearns, Peter N. Childhood in World History (2011)

- West, Elliott. Growing Up in Twentieth-Century America: A History and Reference Guide (1996) online edition

- Wilson, Adrian. "The Infancy of the History of Childhood: An Appraisal of Philippe Aries," History and Theory 19 (1980): 132-53