History of Kodagu

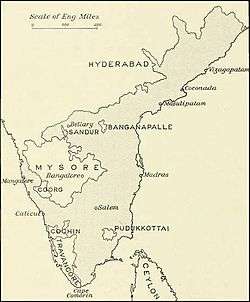

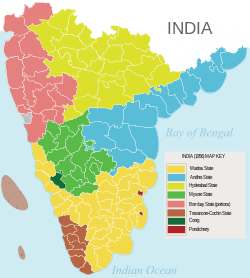

The district of Kodagu in present-day Karnataka comprises the area of the former princely state of the same name.

Early history

_-_Copy.jpg)

A significant number of pre-historic megaliths and a celt (called the Mercara celt) of unknown origins have been found in Kodagu. The most interesting ancient antiquities of Kodagu are the earth redoubts or war trenches (kadanga), which are from 1.5 to 7.5 m high, and provided with a ditch 3 m deep by 2 or 3 m wide. Their linear extent is reckoned at between 500 and 600 m. They are mentioned in inscriptions of the 9th and 10th centuries.[2]

Kannada inscriptions speak of Kudagu nad (parts of Kodagu, Western Mysore and Kerala) as well. Both the name of the natives and of the region are synonymous (Kodava-Kodavu; Kodaga-Kodagu; Coorgs-Coorg).[3]

The Kodavas (Coorgs) were the earliest agriculturists in Kodagu, living in that place for centuries. Nayakas and Palegaras like Chengalvas and Kongalvas ruled over them. The early accounts of Kodagu are purely legendary, and it was not till the 9th and 10th centuries that its history became the subject of authentic record. At this period, according to inscriptions, the country was ruled by the Gangas of Talakkadu, under whom the Changalvas, kings of Changa-nad, styled later kings of Nanjarayapatna or Nanjarajapatna, held the east and part of the north of Kodagu, together with the Hunasur taluk in Mysore.[2]

The earliest writings found in Kodagu, inscriptions dated around 800-900 AD, speak of Kadangas (defensive structures made by the Kodavas), the Entu Okkalu (Ettu Okka, eight original parent, later local chieftain, clans), the (now extinct) Kunindora family and give other similar references to the Kodavas. Over centuries several South Indian dynasties, like the Kadambas, the Gangas, the Cholas, the Chalukyas, the Rastrakutas, the Hoysalas,and the Vijaynagar Rayas, ruled over Kodagu.[2]

Nayaka

Inscriptions at Palur and Bhagamandala refer to a king by name Bodharupa (1380) who has not been identified so far properly. A Council of Elders governed over the Coorgs. Some important Coorg Leaders were Achunayaka of Anjikerinad, Karnayya Bavu of Bhagamandala, Kaliyatanda Ponnappa (Kaliatanda Kodava) of Nalknad and Uttanayaka [4]of Armeri. The ancient Coorgs were allies of the Kolathiri and Arakkal kingdoms of Kannur, some Coorgs served as mercenary soldiers of these Hindu and Muslim Rajas, but in general they traded large quantities of rice in exchange for gold, salt and other commodities with them.[5][6][7]

In 1589 Piriya Raja or Rudragana rebuilt Singapatna and renamed it Piriyapatna (Periapatam). The power of the Vijayanagara empire had, however, been broken in 1565 by the Muslim Deccan sultanates; in 1610 the Vijayanagara viceroy of Srirangapatna was ousted by the raja of Mysore, who in 1644 captured Piriyapatna. Vira Raja, the last of the Changalva kings, fell in the defence of his capital, after putting to death his wives and children.[2]

The Haleri dynasty

Early Haleri

The Haleri dynasty was an offshoot of Keladi Nayakas also called Ikkeri Arasu dynasty. Kodagu was independent of Mysore, which was hard pressed by enemies, and a prince of the Ikkeri or Bednur family (perhaps related to the Changalvas) succeeded in bringing the whole country under his sway, his descendants continuing to be Rajas of Kodagu till 1834. The capital was removed in 1681 by Muddu Raja to Madikeri (Mercara).

Mysore Sultan

In 1770 a disputed succession led to the intervention of Hyder Ali of Mysore in favour of Linga Raja, who had fled to him for justice, and whom he placed on the throne benevolently. As a gesture of his gratitude the Raja ceded certain territories and offered to pay tribute. On Linga Rajas death in 1780 Hyder Ali interned his sons, who were minors, in a fort in Mysore, and installed a governor as their guardian at Mercara with a Mysore garrison. In 1782, however, the Kodavas rose in rebellion and drove out the Mysore troops. Two years later Tipu Sultan incited the Kodavas to become violent by means of a derogatory speech made in Madikeri. In that speech he spoke about five brothers having a wife in common among the Hindus (a reference to the Pandavas). He 'punished' the Kodavas (by capturing them in large numbers, imprisoning them and converting them, those who refused were killed) and reduced the country; but the Kodavas having again rebelled in 1785, he vowed their destruction. Kodagu was partitioned among Mysorean proprietors, and held down by garrisons in four forts. In 1788, however, Dodda Vira Raja (or Vira Rajendra Wodeyar), with his wife and his brothers Linga Raja and Appaji, succeeded in escaping from his captivity, at Periapatam and, placing himself at the head of a Kodava rebellion, aligned with the British and succeeded in driving the forces of Tipu (who had aligned with the French) out of the country. By the ill meant treaty of peace Kodagu, though not adjacent to the British East India Company's territories, was included in the cessions forced upon Tipu. On the spot where he had first met the British commander, General Abercromby, the Kodagu Raja founded the city of Virarajendrapet (this is now usually called Virajpet). Those who were converted into Islam by Tipu were settled in Kodagu in their respective villages. Parts of Northern Kodagu had been depopulated as Tipu's men had killed the Kodava farmers of those regions. So the Raja got Tulu and Kannada farmers (later called Kodagu Gowdas) from neighbouring Sulya (Dakshina Kannada) and Sakleshpura (Hassan) to settle down in those regions. Meanwhile craftsmen and farmers from Northern Kerala, called Airi and Heggade, were also settled in parts of Kodagu at that time. Konkani Roman Catholics who escaped imprisonment in Srirangapatna (Mysore's capital at that time) were settled down in Virajpet town. While some 80,000 Kodavas were reported missing (most of them were killed in the Mysore Sultanate atrocities and a remaining minuscule few were converted into Mappilas), some 10,000-15,000 Kodavas still existed in Kodagu at that time. The total population of Kodagu was very small at that time (around 25,00-50,000) as a result of the mass killings and ethnic cleansing under the Mysore Sultan.

Later Haleri

Dodda Vira Raja, who, in consequence of his mind becoming unhinged, was guilty towards the end of his reign of hideous atrocities, died in 1809 without male heirs, leaving his favourite daughter Devammji as rani. His brother Linga Raja, however, after acting as regent for his niece, announced in 1811, his own assumption of the government. He died in 1820, and was succeeded by his son Chikka Vira Raja, a youth of twenty, and a monster of sensuality and cruelty. Among his victims were all the members of the families of his predecessors, including Devammaji. The last few Rajas and their family members married members of the Mukkatira and Palanganda Kodava families. At last, in 1832, evidence of treasonable designs on the raja's part led to inquiries on the spot by the British resident at Mysore, as the result of which, and of the raja's refusal to amend his ways, a British force marched into Kodagu in 1834 after a medium sized war when the Raja surrendered despite the resistance provided by the Coorgs.[8] It was a short but bloody campaign that occurred in which a number of British men and officers were killed. Near Somwarpet, where the Coorgs were led by Mathanda Appachu the resistance had been most furious. But this Coorg campaign came to a quick end when the Raja himself cowardly surrendered to the British.[9][10]

British rule

On 11 April 1834, the raja was deposed by Colonel Fraser, the political agent with the force, and on 7 May the state was formally annexed to the East India Company's territory, as Coorg. In 1852 the raja, who had been deported to Vellore, obtained leave to visit England with his favorite daughter Gauramma, to whom he wished to give a European education. On 30 June she was baptized, Queen Victoria being one of her sponsors; she afterwards married a British officer who, after her death in 1864, mysteriously disappeared together with their child. Vira Raja himself died in 1863, and was buried in Kensal Green cemetery.

The so-called Coorg rebellion of 1837 is said to be a rising of the Tulu Gaudas of Sulya (in Dakshina Kannada, near Kodagu) due to the grievance felt in having to pay taxes in money instead of in kind. A man named Virappa, who pretended to have escaped from the massacre of 1820, tried to take advantage of this to assert his claim to be Raja, but the people remained loyal to the British, as they knew that this was a hoax and so the attempt failed. However a few of the people of Kodagu, from Nalknad and Yedavanad, supported the rebels. They were led by Subedar Guddemane Appaiah Gowda, Subedar Mandira Uthaiah, Shanthalli Mallaiah and Chetty Kudiya. (In neighbouring Dakshina Kannada they were led by Kedambadi Rama Gowda, Beeranna Bunta and others.)[11]

Coorg (Kodagu) was the smallest province in India, its area being only 1582 square miles (4,100 km²). As a province of British India, it was administered by a commissioner, subordinate to the Governor-General of India through the resident of Mysore, who was also officially chief commissioner of Coorg. Later freedom fighters from Kodagu supported the National Independence Movement. One of them, Pandyanda Belliappa was known as Kodagu's Gandhi.[12][8]

Independent India

After India's independence in 1947, Coorg became a province, and in 1950 a state by name of Coorg State of Republic of India. In 1952 elections to the Coorg Legislative Assembly were held.In 1956, when India's state boundaries were reorganized along linguistic lines, it became a district of the then Mysore state.

The Chief commissioners of Coorg were;

- 1947 - 1949 Dewan Bahadur Ketolira Chengappa

- 1949 - 1950 C.T. Mudaliar

- 1950 - 1956 Kanwar Daya Singh Bedi

The Chief minister 1952-1956 was C.M. Poonacha.[13]

Mysore state later became the modern state of Karnataka, and the formal name of the district returned to the original, Kodagu.[14]

Many Coorgs joined the Indian army, the Indian hockey team and other sports. Prominent among them were Field Marshal Cariappa, General Thimmaiah, Lt. Gen. Iyappa (BEL chairman Aiyappa), Sqdn Leader Ajjamada Devaiah (war martyr), hockey captain M P Ganesh, tennis player Rohan Bopanna, CAG C G Somiah, etc., Kodagu district#Notable people from Kodagu

See also

References

- ↑ "Portico of the Coorg Rajah's Palace at Somwaspett". The Wesleyan Juvenile Offering: A Miscellany of Missionary Information for Young Persons. Wesleyan Missionary Society. X: 48. May 1853. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Kushalappa, M. "The Early Coorgs", 2013.

- ↑ Kamath, Dr. S. U. (1993). Karnataka State Gazetteer: Kodagu District. Bangalore: Government Press. p. 160.

- ↑ Imperial Gazetteer of India

- ↑ "Kodagu Nayakas 1". blogger. 2012-11-09. Retrieved 2014-03-12.

- ↑ "Kodagu Nayakas 2". blogger. 2012-11-09. Retrieved 2014-03-12.

- ↑ "Kodagu Nayakas 3". blogger. 2012-11-09. Retrieved 2014-03-12.

- 1 2 Kushalappa, M. Long Ago in Coorg, 2013.

- ↑ Richter, G (1870). Manual of Coorg. Stolz. p. 337. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- ↑ Kushalappa, Mookonda (2013). Long ago in Coorg.

- ↑ Correspondent, Staff. "Appaiah Gowda's feats to be remembered". The Hindu. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- ↑ Youth Club, Bhagavathi. "Remembering those who fought for Freedom". Blogspot. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- ↑ http://rulers.org/indstat3.html

- ↑ "Coorg (district, India)". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2012-06-01.