Historiography of Colonial Spanish America

The historiography of Spanish America has a long history,[1][2][3] dating back to revisionist accounts of the conquest, Spaniards’ eighteenth-century attempts to understand the apparent decline in its empire and ways to revive it,[4] and American-born Spaniards (creoles') search for identity separate from Spain's and the creation of creole patriotism.[5] Following independence in some parts of Spanish America, some politically-engaged citizens new sovereign nations sought to shape national identity.[6] In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, non-Spanish American historians began writing chronicles important events, such as the conquests of Mexico and Peru,[7] dispassionate histories of the Spanish imperial project after its almost complete demise in the hemisphere,[8] and histories of the southwest borderlands, areas of the United States that had previously been part of the Spanish empire, led by Herbert Eugene Bolton.[9] At the turn of the twentieth century, scholarly research on Spanish America saw the creation courses dealing with the region, the systematic training of professional historians in the field, and the founding of the first specialized journal, Hispanic American Historical Review.[10][11] For most of the twentieth century, historians of colonial Spanish America read and were familiar with a large canon of work. With the expansion of the field in the late twentieth century, there has been the establishment of new subfields, the founding of new journals, and the proliferation of monographs, anthologies, and articles for increasingly specialized practitioners and readerships.

General works

A number of general works have focused on the colonial era and provide an overview. A short but classic general history is Charles Gibson's Spain in America.[12] A major textbook comparing Spanish America and Brazil is James Lockhart and Stuart B. Schwartz's 1983 Early Latin America, which argues that Spanish America and Brazil were structurally similar. Its annotated bibliography of important works in the field remains important, but many significant studies have been published since 1983.[13] New emphases, such as women, indigenous, and blacks as groups and as political actors in rebellion and other resistance to colonial regimes.[14] A standard work on colonial Latin America that has gone through multiple editions is Mark Burkholder and Lyman L. Johnson's Colonial Latin America.[15] Collections of primary source documents have been published, which are especially useful for classroom use.[16][17][18][19]

There are relatively few general works on in English on a single country, but Mexico has been the subject of a number of histories.[20][21][22] Two general works concentrating on the colonial period are by Ida Altman and coauthors.[23] and Alan Knight.[24]

Useful historiographical essays on colonial Spanish America include ones in the The Oxford Handbook of Latin American History[25] on New Spain,[26] colonial Spanish South America,[27] sexuality,[28] and the independence era.[29] Useful essays by major figures in the field have appeared journals over the years.[30][31][32] The Handbook of Latin American Studies publishes annotated bibliographies of new works in the field, with contributing editors providing an overview essay.

Early historiography

From the early sixteenth century onward, Spaniards wrote accounts of Spain's overseas explorations, conquests, religious evangelization, the overseas empire. The authors range from conquerors, crown officials, and religious personnel.[33][34] The early development of the idea of Spanish American local patriotism, separate from Spanish identity, has been examined through the writings of a number of key figures, such as Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, Bartolomé de las Casas, Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas, Fray Juan de Torquemada, Francisco Javier Clavijero, and others.[35] Spaniards grappled with how to write their own imperial history and Spanish Americas created a "patriotic epistemology."[36]

_Brevisima_relaci%C3%B3n_de_la_destrucci%C3%B3n_de_las_Indias.png)

European rivals of Spain wrote a number of polemics, characterizing the Spanish as cruel, bigoted, and exploitative. The so-called Black Legend drew on Bartolomé de Las Casas's contemporary critique, A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies (1552) and became an entrenched view of the Spanish colonial era.[37][38] Defenders of the Spanish attempts to defend the Indians from exploitation created what was called the White Legend of Spanish tolerance and protection of the Indians.[39] The question was debated in the mid to late twentieth century and continues to have some salience in the twenty-first.[40][41][42]

Scottish scholar William Robertson (1721-1793), who established his scholarly reputation by writing a biography of Spain's Charles V, wrote the first major history in English of Spanish America, The History of America (1777). The work paraphrases much of Spanish historian Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas's Décadas, it also contained new sources. It reached a wide readership when Britain was rising as a global empire. Robertson drew on Las Casas's A Short Account, of Spanish cruelty, he noted Las Casas likely exaggerated.[43] Spanish historians debated whether to translate Robertson's history to Spanish, which proponents supported because of Robertson's generally even-handed approach to Spanish history, but the project ultimately shelved when powerful politician José de Gálvez disapproved.[44]

Scholars in France, particularly Comte de Buffon (1707-1788), Guillaume Thomas François Raynal (1713-1796) and Cornelius de Pauw (1739-1799), whose works generally disparaged Americas and its populations the region, which Iberian-born ("peninsular ") and American-born Spaniards ("criollos")sought to counter.[45][46]

A major figure in Spanish American history and historiography is Prussian scientist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt.[47] His five-year scientific sojourn in Spanish America with the approval of the Spanish crown, contributed new knowledge about the wealth and diversity of the Spanish empire. Humboldt's self-funded expedition from 1799-1840 was the foundation of his subsequent publications that made him the dominant intellectual figure of the nineteenth century. His Political Essay on the Kingdom of New Spain was first published in French in 1810 and was immediately translated to English.[48] Humboldt's full access to crown officials and their documentary sources allowed him to create a detailed description of Spain's most valuable colony at the turn of the nineteenth century. "In all but his strictly scientific works, Humboldt acted as the spokesman of the Bourbon Enlightenment, the approved medium, so to say, through which the collective inquiries of an entire generation of royal officials and creole savants were transmitted to the European public,t heir reception assured by the prestige of the author."[49]

In the early post-independence era, history writing in the nations of Spanish America was accomplished by those from a particular country or region. Often these writings are part of the creation of a national identity from a particular political viewpoint. Politically conservative historians looked to the colonial era with nostalgia, while politically liberal historians considered the colonial era with disdain. An important example is Mexico's conservative politician and intellectual Lucas Alamán. His five-volume Historia de Mejico is the country's first history, covering the colonial era up to and including the struggle for independence. Alamán viewed crown rule during the colonial era as ideal, and political independence that after the brief monarchy of Agustín de Iturbide, the Mexican republic was characterized by liberal demagoguery and factionalism.[50] Writing in the mid-nineteenth century, Mexican liberal Vicente Riva Palacio, grandson of insurgent hero Vicente Guerrero, wrote a five-volume history of the colonial era from a liberal viewpoint,[51][52] During the era of Porfirio Díaz (1876-1911), writing a new history of Mexico became a priority and Justo Sierra, minister of education, wrote an important work, The Political Evolution of the Mexican People (1900–02), whose first two major sections deal with "aboriginal civilizations and the conquest" and the colonial era and independence .[53]

In the United States, the work of William Hickling Prescott (1796-1859) on the conquests of Mexico and Peru became best sellers in the mid-nineteenth century, but were firmly based on printed texts and archival sources.[54] Prescott's work on the conquest of Mexico was almost immediately translated to Spanish for a Mexican readership, even though it had an underlying anti-Catholic bias. For conservative Mexicans, Prescott's description of the Aztecs as "barbarians" and "savages" fit their notion of the indigenous and the need for the Spanish conquest.[55]

The U.S. victory in U.S.-Mexican war (1846–48), when it gained significant territory in western North America, incorporated territory previously held by Spain and then independent Mexico and in the U.S. the history of these now-called Spanish borderlands became a subject for historians.[56] In the U.S. Hubert Howe Bancroft was a leader in the development of the history of Spanish American history and the borderlands.[57] His multivolume histories of various regions of northern Spanish America were foundational works in the field, although sometimes dismissed by later historians, "at their peril."[58] He accumulated a vast research library, which he donated to University of California, Berkeley. The Bancroft Library was a key component to the emergence of the Berkeley campus as a center for the study Latin American history. A major practitioner of the field was Berkeley professor Herbert E. Bolton, who became director of the Bancroft Library. As President of the American Historical Association laid out his vision of an integrated history of the Americas in "The Epic of Greater America".[59]

Starting around the turn of the twentieth century, university-level courses on Latin American history were created and the number of historians trained in the use of "scientific history," using primary sources and even-handed approach to the writing of history increased. Early leaders in the field founded the Hispanic American Historical Review in 1918, and then as the number of practitioners drew, they founded the professional organization of Latin American historians, the Conference on Latin American History in 1926. The development of Latin American history was first examined in a two-volume collection of essays and primary sources, prepared for the Conference on Latin American History,[60] and in a monograph by Helen Delpar, Looking South: The Evolution of Latin Americanist Scholarship in the United States, 1850-1975.[61] For more recent history of the field in Great Britain, see Victor Bulmer-Thomas, ed. Thirty Years of Latin American Studies in the United Kingdom 1965-1995.[62]

European Age of Exploration and the early Caribbean

The European age of expansion or the age of exploration focuses on the period from the European point of view: crown sponsorship of voyages of exploration, early contacts with indigenous peoples, and the establishment of European settlements.[63] Early European settlements in the Caribbean and the role of the family of Genoese mariner Christopher Columbus have been the subject of a number of studies.[64][65] Historical geographer Carl O. Sauer's The Early Spain Main remains a classic publication.[66] The 500th anniversary of Columbus's first voyage was marked with a large number of publications, a number of which emphasize the indigenous as historical actors, helping to create a fuller and more nuanced picture of historical dynamics in the Caribbean.[67] Ida Altman's study of the rebellion of the indigenous leader Enriquillo includes a very useful discussion of the historiography of the early period.[68]

Historiography of the conquest

The history of the Spanish conquest of Mexico and of Peru has long fascinated scholars and the general public. With the quincentenary of the first Columbus voyage in 1992, there has been a renewed interest in the very early encounter between Europeans and New World indigenous peoples.[69] Sources for the histories of the conquest of Mexico are particularly rich, and the historiographical debates about events and interpretations from multiple viewpoints inform the discussions.[70]

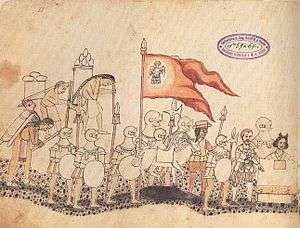

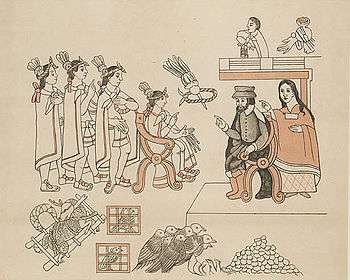

Spanish conqueror Hernán Cortés wrote to Charles V during the events of the conquest, attempting to his explain his actions and demonstrate the importance of the conquest. Bernal Díaz del Castillo wrote important accounts of the conquest, and other, less prominent Spanish conquerors petitioned the crown to garner rewards from the crown. In addition to these accounts by the European winners, are ones by their indigenous allies, particularly the Tlaxcalans and Texcocans, but also the defeated rulers of Mexico-Tenochtitlan. A "vision of the vanquished" was recorded by sixteenth-century Franciscan, Bernardino de Sahagún as the last volume of his General History of the Things of New Spain, often known as the Florentine Codex.

Revisionist history of the conquest was being written as early as the sixteenth century. Accounts by Spanish participants and later authors have long been available, starting with the publication of Hernán Cortés's letters to the king, Francisco López de Gómara's biography of Cortés commissioned by Cortés's son and heir Don Martín. That laudatory biography prompted an irate Bernal Díaz del Castillo to write his "true history" of the conquest of Mexico, finished in 1568, but first published in 1632. Multiple editions of Cortés's letters and Bernal Díaz del Castillo's "true history" have appeared over the years. Accounts from the various Nahua perspectives have appeared, including Franciscan Bernardino de Sahagún's two accounts of the conquest from the Tlatelolco viewpoint, book XII of the Florentine Codex,[71][72][73] Anthologies of accounts of the conquest from additional Nahua perspectives have appeared.[74][75][76] Spanish accounts of the conquest of Yucatán have been available in print, but now accounts by Maya conquerors have been published in English translation.[77] The so-called "new conquest history" aims to encompass any encounter between Europeans and indigenous peoples in contexts beyond complex indigenous civilizations and European conquerors.[78]

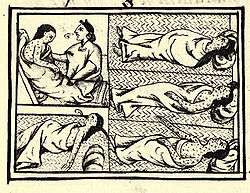

Demography

The catastrophic fall in the indigenous populations of Spanish America was evident from the first contacts in the Caribbean, something that alarmed Bartolomé de las Casas. The impacts of the demographic collapse has continued to garner attention following the early studies by Sherburne F. Cook and Woodrow Borah, who examined censuses and other materials to make empirical assessments.[79] The question of sources and numbers continues to be an issue in the field, with David P. Henige’s Numbers from Nowhere, a useful contribution.[80] Nobel David Cook’s Born to Die [81] as well as Alfred Crosby’s The Columbian Exchange are valuable and readable accounts of epidemic disease in the early colonial period. Regional studies of population decline have appeared for a number of areas including Mexico, Peru, Honduras, and Ecuador. The moral and religious implications of the collapse for Spanish Catholics is explored in an anthology with case studies from various parts of colonial Spanish America, The Secret Judgments of God.[82] Religious and moral interpretations of disease gave way in the eighteenth century to scientific public health responses to epidemics.[83][84][85]

Institutional history

The institutional history of Spain's and Portugal's overseas empires was an early focus of historiography. Laying out the structures of crown rule (civil and ecclesiastical) created the framework to understand how the two overseas empires functioned. An early study in English of Spanish America was Edward Gaylord Bourne's four-volume Spain in America (1904), a historian who "viewe[ed] the Spanish colonial process dispassionately and thereby escape[d] the conventional Anglo-Protestant attitudes of outraged or tolerant disparagement." [86] In 1918 Harvard professor of history Clarence Haring published a monograph examining the legal structure of trade in the Hapsburg era, followed by his major work on the Spanish empire (1947).[87][88] One of the few women publishing scholarly works in the early twentieth century was Lillian Estelle Fisher, whose studies of the viceregal administration and the intendant system were important contributions.[89][90] Other important works dealing with institutions are Arthur Aiton's biography of the first viceroy, Don Antonio de Mendoza, who set many patterns for future administrators in Spanish America.[91] and J.H. Parry on the high court of New Galicia and the sale of public office in the Spanish empire.[92][93] Scholars have subsequently examined how flexible the Spanish bureaucracy was in practice.[94] Woodrow Borah's Justice By Insurance (1983) shows how the Spanish crown's establishment of tax-funded legal assistance to Indians in Mexico provided the means for indigenous communities to litigate in the Spanish courts.[95] A useful general examination in the twenty-first century is Susan Elizabeth Ramírez, "Institutions of the Spanish American Empire in the Hapsburg Era"[96]

Church-state relations and religion in Spanish America have also been a focus of research, but in the early twentieth century, it did not receive as much attention as the subject merits. What has been called the "spiritual conquest," the early period of evangelization in Mexico, has received considerable treatment by scholars.[97] Another classic publication on the period is John Leddy Phelan's work on the early Franciscans in Mexico.[98] The Holy Office of the Inquisition in Spanish America has been a subject of inquiry since Henry Charles Lea's works at the turn of the twentieth century.[99] In the twentieth century, Richard E. Greenleaf examined the Inquisition as an institution in sixteenth-century Mexico.[100] Later work on the Inquisition has used it voluminous records for writing social history in Mexico and Peru.

The Bourbon Reforms of the late eighteenth century have been more broadly studied, examining the changes in administrative arrangements with the Spanish crown that resulted in the intendancy system.[101][102][103]

An important shift in church-state relations during the Bourbon Reforms, was the crown's attempt to rein in the privileges of the clergy as it strengthened the prerogatives of the crown in a position known as regalism.[104] Pamela Voekel has studied cultural aspects of the Bourbon reforms on religion and popular piety.[105]

Trade and commerce in the Bourbon era have been examined, particularly the institution of comercio libre, the loosening of trade strictures within the Spanish empire.[106][107] The administrative reorganization opened up new ways for administrators and merchants to exploit the indigenous in Mexico via forced sale of goods in exchange for red dye production, cochineal, which was an extremely valuable commodity.[108][109]

In the late eighteenth century Spain was forcibly made aware in the Seven Years' War by the capture of Havana and Manila by the British, that it needed to establish a military to defend its empire. The crown established a standing military and filled its ranks with locals.[110][111][112][113][114]

Social history

Scholars of Latin America have focused on characteristics of the region's populations, with particular interest in social differentiation and stratification, race and ethnicity, gender, sexuality, and family history, and the dynamics of colonial rule and accommodation or resistance to it. Social history as a field expanded its scope and depth beginning in the 1960s, although it was already developed as a field previous to that. An important 1972 essay by James Lockhart lays out a useful definition, "Social history deals with the informal, the unarticulated, the daily and ordinary manifestations of human existence, as a vital plasma in which all more formal and visible expressions are generated."[115] Archival research utilizing untapped sources or those only partially utilized previously, such as notarial records, indigenous language materials, have allowed new insights into the functioning of colonial societies, particularly the role of non-elites. As one historian put it in 1986, "for the social historian, the long colonial siesta has long given way to sleepless frenzy."[116]

Conquest era

The social history of the conquest era shift in the way the period is treated, focusing less on events of the conquest and more on its participants. James Lockhart's path-breaking Spanish Peru (1968) concerns the immediate post-conquest era of Peru, deliberately ignoring the political events of the internecine conflicts between Spanish factions. Instead it shows how even during that era, Spanish patterns took hold and a multiracial colonial society took shape.[117] His companion volume, The Men of Cajamarca examines the life patterns of the Spanish conquerors who captured the Inca emperor Atahualpa at Cajamarca who paid a huge ransom in gold for his freedom, and then murdered. The prosopographical study of these conquerors records as much extant information on each man in existing sources, with a general essay laying out the patterns that emerge from the data.[118] A comparable work for the early history of Mexico is Robert Himmerich y Valencia's work on encomenderos.[119] New research on encomenderos in Spanish South America has appeared in recent years.[120][121][122]

Gender as a factor in the conquest era has also shifted the focus in the field. New work on Doña Marina/Malinche, Hernán Cortés's consort and cultural translator sought to contextualize her as a historical figure with a narrow range of choices. The work has aided the rehabilitation of her reputation from being a traitor to "her" people.[123][124] The role of women more generally in the conquest has been explored for the Andean region.[125]

The role of blacks in the conquest is now being explored,[126] as well as Indians outside the main conquests of central Mexico and Peru.[127]

Elites

_Cervantes_-_Miguel_Cabrera_-_overall.jpg)

The history of elites and the role of economic stratification remain important in the field, although there is now a concerted effort to expand research to non-elites.[128][129][130]

Among elites are crown officials, high churchmen, mining entrepreneurs, and transatlantic merchants, enmeshed in various relationships wielding or benefiting from power. Elites lived in cities, the headquarters and nexus of civil and religious hierarchies and their large bureaucracies, the hubs of economic activity, and the residence of merchant elites and the nobility. A large number of studies of elites focus on particular cities: vicregal capital and secondary cities, which had a high court (audiencia) and the seat of a bishopric, or were ports from overseas trade. The intersection of silver entrepreneurs and elites in Mexico has been examined in D.A. Brading's classic Miners and Merchants in Bourbon Mexico, 1763-1810, focusing on Guanajuato and in Peter Bakewell's study of Zacatecas.[131][132] Merchants in Mexico City have been studied as a segment of elites for Mexico City in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.[133][134][135] as well as merchants in late colonial Veracruz.[136] Merchants in other areas have been studies as well.[137][138]

Studies of ecclesiastics as a social grouping include one on the Franciscans in sixteenth-century Mexico,[139] For eighteenth-century Mexico William B. Taylor's Magistrates of the Sacred on the secular clergy is a major contribution.[140] An important study on the secular clergy in eighteenth-century Lima has yet to be published as a monograph.[141] In recent years, studies of elite women who became nuns and the role of convents in colonial society have appeared.

Indigenous Peoples

In the twentieth century, historians and anthropologists of studying colonial Mexico worked to create a compendium of sources of Mesoamerican ethnohistory, resulting in four volumes of the Handbook of Middle American Indians being devoted to Mesoamerican ethnohistorical sources.[142] Two major monographs by historian Charles Gibson, the first on the post-conquest history of Tlaxcala, the indigenous polity that allied with Cortés against the Mexica, and the second, his monumental history of the Aztecs of central Mexico during the colonial era, were published by high-profile academic presses and remain classics in Spanish American historiography. Gibson was elected president of the American Historical Association in 1977, indicating how mainstream Mesoamerican ethnohistory had become.[143][144] Litigation by Mexican Indians in Spanish courts in Mexico generated a huge archive of information in Spanish about how the indigenous adapted to colonial rule, which Gibson and other historians have drawn on.[145][146] Scholars utilizing texts in indigenous languages have expanded the understanding the social, political, and religious history of indigenous peoples, particularly in Mexico.[147][148]

Indigenous history of the Andean area has expanded significantly in recent years.[149][150] Andean peoples also petitioned and litigated in the Spanish courts to forward their own interests.[151][152]

The topic of indigenous rebellion against Spanish rule has been explored in central and southern Mexico and the Andes. One of the first major rebellions in Mexico is the 1541 Mixtón War, in which indigenous in central Mexico's west rose up and a full-scale military force led by New Spain's first viceroy.[153] Work on rebellion in central Mexican villages showed that they were local and generally short-lived.[154] and in the southern Maya area there were more long standing patterns of unrest with religious factors playing a role.[155][156] Seventeenth-century rebellions in northern Mexico have also garnered attention.[157]

Andean resistance and rebellion have increasingly been studied as a phenomenon. The indigenous writer Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala (1535-ca. 1626) who authored El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno has garnered significant attention. The nearly 1,200-page, richly illustrated manuscript by an elite Andean is a critique of Spanish rule in the Andes that can be considered a lengthy petition to the Spanish monarch to ameliorate abuses of colonial rule.[158] General accounts of resistance and rebellion have been published.[159][160] The great eighteenth-century rebellion of Tupac Amaru that challenged colonial rule has been the focus of much scholarship.[161][162][163][164]

Race

The study of race dates to the earliest days of the Spanish empire, with debates about the status of the indigenous – whether they had souls, whether they could be enslaved, whether they could be Catholic priests, whether they were subject to the Inquisition. The decisions steered crown and ecclesiastical policy and practices. With the importation of Africans as slaves during the early days of European settlement in the Caribbean and the emergence of race mixture, social hierarchies and racial categories became complex. The legal division between the República de indios, that put the indigenous population in a separate legal category from the República de españoles that included Europeans, Africans, and mixed-race castas was the crown’s policy to rule its vassals with racial status as one criterion.

Much scholarly work has been published in recent years on social structure and race, with an emphasis on how Africans were situated in the legal structure, their socioeconomic status, place within the Catholic Church, and cultural expressions. Modern studies of race in Spanish America date to the 1940s with the publication of Gonzalo Aguirre Beltrán’s monograph on Africans in Mexico.[165] In the United States, the 1947 publication of Frank Tannenbaum’s Slave and Citizen: The Negro in the Americas cast Latin American slavery as more benevolent compared to that in the United States. In Tannenbaum's work, he argued that although slaves in Latin America were in forced servitude, they incorporated into society as Catholics, could sue for better treatment in Spanish courts, had legal routes to freedom, and in most places abolition was without armed conflict, such as the Civil War in the U.S.[166] The work is still a center of contention, with a number of scholars dismissing it as being wrong or outdated, while others consider the basic comparison still holding and simply no longer label it as the "Tannenbaum thesis."[167]

The 1960s marked the beginning of an upsurge in studies of race and race mixture. Swedish historian Magnus Mörner’s 1967 Race Mixture in the History of Latin America, published by a trade press and suitable for college courses, remained important for defining the issues surrounding race.[168] The historiography on Africans and slavery in Latin America was examined in Frederick Bowser’s 1972 article in Latin American Research Review, summarizing research to date and prospects for further investigation. His major monograph, The African Slave in Colonial Peru, African Slave in Colonial Peru, 1524-1650, marked a significant advance in the field, utilizing rich archival sources and broadening the research area to Peru.[169][170]

The debates about race, class, and “caste” took off in the 1970s with works by a number of scholars.[171][172][173][174][175][176] Scholars have been also interested in how racial hierarchy has been depicted visually in the eighteenth-century flowering of the secular genre of casta painting. These paintings from the elite viewpoint show racial stereotypes with father of one race, mother of another, and their offspring labeled in yet another category.[177][178][179]

Elites’ concern about racial purity or "limpieza de sangre" (purity of blood), which in Spain largely revolved around whether one was of pure Christian heritage, in Spanish America encompassed the "taint" of non-white admixture. A key work is María Elena Martínez’s Genealogical Fictions, showing the extent to which elite families sought erase blemishes from genealogies.[180] Another essential work to understand the workings of race in Spanish America is Ann Twinam’s work on petitions to the crown by mulattos and pardos for dispensation from their non-white status, to pursue education or a profession, and later as a blanket request not tied to professional rules prohibiting non-whites to practice. In the decades following Tannenbaum's work, there were few of these documents, known cédulas de gracias al sacar,, with just four cases identified, but the possibility of upward social mobility played an important role in framing scholarly analysis of dynamics of race in Spanish America.[181] Considerable work on social mobility preceded that work, with R. Douglas Cope’s The Limits of Racial Domination remaining important.[182]

The incorporation of blacks and indigenous into Spanish American Catholicism meant that they were part of the spiritual community. The Church did not condemn slavery as such. The Church generally remained exclusionary in the priesthood and kept separate parish registers for different racial categories. Black and indigenous confraternities (cofradías) provided a religious structure for reinforcement of ties among their members.[183][184][185]

Work on blacks and Indians, and mixed categories, has expanded to include complexities of interaction not previously examined. Works by Matthew Restall and others explore race in Mexico.[186][187][188] There is also new work on the colonial Andes as well.[189][190][191][192]

Gender, sexuality, and family

Women's history developed as a field of Spanish American history in tandem with its emergence in the U.S. and Europe.[193][194][195] Studies of elites generally has led to the understanding of the role of elite women in colonial Spanish America as holders of property, titles, and repositories of family honor.[196][197][198]

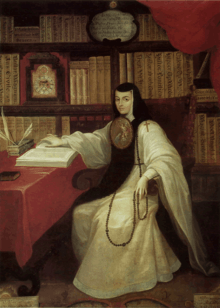

Early works on Mexican nun Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz,a singular seventeenth-century poet, famous in her own time,[199][200] widened to study elite women who were eligible to become nuns, and further expanded to examine the lives of ordinary, often mixed-race, urban women.[201] Nuns and convents have been well studied.[202][203] Spanish American holy women such as Saint Rose of Lima and the Lily of Quito, beatas, as well as the popular saint of Puebla, Mexico, Catarina de San Juan, have been the subject of recent scholarly work.[204][205]

Gender has been the central issue of recent works on urban and indigenous women.[206][207] The role of indigenous women in colonial societies has been explored in a series of recent works.[208][209][210][211]

The history of sexuality has expanded in recent years from studies of marriage and sexuality[212] to homosexuality,[213] and other expressions of sexuality,[214][215] including bestiality.[216] Of particular note is Ann Twinam's work on honor and illegitimacy in the colonial era;[217] there is a similar work for Peru.[218] The memoir of the nun-turned-cross-dressing soldier, Catalina de Erauso, is a picaresque tale and one of the few autobiographies form the colonial era.[219] The problem of priests soliciting sexual favors in the confessional box and church responses to the abuse draws on Inquisition cases.[220]

Records of the Holy Office of the Inquisition have been a fruitful archival source on women in Mexico and Peru, which include women of color. Inquisition records by definition record information about those who have run afoul of the religious authorities, but they are valuable for preserving information on mixed-race and non-elite men and women and the transgressions, many of which were sexual, that brought them before the tribunal.[221][222]

Women have been studied in the context of family history, such as the work of Pilar Gonzalbo Aizpuru and others.[223][224] The history of children in Spanish America has become a recent focus.[225][226]

Religion and culture

Art and architecture played an important role in creating visible embodiments of religious culture, with images of saints and religious allegories, and churches that ranged from magnificent cathedrals to humble parish churches and mission chapels. Colonial architecture in Mexico has been the subject of a number of important studies, with church architecture as a significant component. Replacing sacred worship spaces of the ancient religion with visible manifestations of Christianity was a high priority for the "spiritual conquest" of the early evangelical period.[227][228][229][230] Studies of architecture in Spanish South America and particularly the Andean region is increasing.[231][232][233][234][235][236]

Until the mid eighteenth century, the subject of most paintings was religious in some form or other, so that the historiography of colonial visual culture is weighted toward religion. Publication on colonial art has a long tradition, especially in Mexico.[237] In recent years there has been a boom in publications on colonial art, with some useful overviews published.[238][239][240][241][242][243] Major exhibitions on colonial art have resulted in fine catalogues as a permanent record, with many examples of colonial religious art.[244][245][246][247][248]

The conversion and incorporation of the indigenous into Christendom was a key aim of Spanish colonialism. There is a long tradition of writings by Spanish religious personnel, but more recently there has been an expansion of research on indigenous Catholicism. In Mexico, indigenous language sources have given new perspectives on religious belief and practice.[249][250][251][252][253][254] For the Maya area, there have been a number of important studies.[255][256] Religion has been an important focus of new work in Andean history, particularly persistence of indigenous beliefs and resistance to Catholic conversion.[257][258]

Rituals and festivals reinforced religious culture in Spanish America. The enthusiasm for expressions of public piety during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were seen as part of "baroque culture."[259] Specific religious celebrations, such as Corpus Christi have been studied in both Mexico and Peru.[260][261] The autos de fe of the Inquisition were public rituals enforcing religious orthodoxy with the participation of the highest civil and religious authorities and throngs of the faithful observing.[262] There were a variety of transgressions that brought men and women before the Inquisition, including practicing Judaism while passing as Catholic (judizantes), bigamy, sexual transgressions, blasphemy, and priests soliciting in the confessional. Mocking religious sacraments could bring one before religious authorities, such as the case of the "marriage" of two dogs in late colonial Mexico.[263]

In the eighteenth century, the crown sought to curtail public manifestations of piety ("baroque display") by bringing in new regulations. Pamela Voekel's Alone Before God: Religious Origins of Modernity in Mexico shows how the crown targeted elaborate funerary rites and mourning as an expression of excessive public piety. Mandating that burials be outside the consecrated ground of churches and church yards but rather in suburban cemeteries, elites pushed back. They had used such public displays as a way of demonstrating their wealth and position among the living and guaranteeing their eternal rest in the best situated places in churches.[264] Another crown target was Carnaval celebrations in Mexico City, which plebeians joined with enthusiasm since Carnaval generally overturned or mocked traditional order, including religious authorities. Also to better ensure public order of plebeians, the crown sought to regulate taverns as well as public drinking, particularly during festivals. Since elites consumed alcohol in their private residences, the regulations were aimed at controlling commoners.[265]

Economic history

Trade and commerce, commodity production, and labor systems have been extensively studied in colonial Spanish America. As with other aspects of colonial history, economic history does not fit neatly into a single category, since it is bound up with crown policy, the existence of exploitable resources, such as silver, credit, capital and entrepreneurs. In the development of the agricultural sector, the availability of fertile soil and adequate water, expanses of land for grazing of cattle and sheep, as well as the availability of labor, either coerced or free were factors. The export economy relying on silver production and to a lesser extent dye for European textile production stimulated the growth of regional development. Profitable production of foodstuffs and other commodities, such as wool, for local consumption marked the development of a colonial economy.

Early labor systems

Following on precedents in Spain following the Catholic reconquest of Muslim Spain, conquerors expected material rewards for their participation, which in that period was the encomienda. In Spanish America, the encomienda was a grant of indigenous labor and tribute from a particular community to private individuals, assumed to be in perpetuity for their heirs. Where the encomienda initially functioned best was in regions where indigenous populations were hierarchically organized and were already used to rendering tribute and labor. Central Mexico and the Andes presented that pattern. The encomienda has an institution has been well studied concerning its impacts on indigenous communities and how Spanish encomenderos profited from the system.[266] James Lockhart examined the shift from encomienda labor awarded to just a few Spaniards, to the attempt by the crown to expand access to labor via the repartimiento to later arriving Spaniards who had been excluded from the original awards. This also had the effect of undermining the growing power of the encomendero group and the shift to free labor and the rise of the landed estate.[267] In Central America, forced labor continued as a system well into the nineteenth century.[268] Regional variations on the encomienda have been studied in Paraguay, an area peripheral to Spanish economic interests. The encomienda there was less labor coercion than mobilizing networks of indigenous kin that Spaniards joined.[269][270]

Slave labor was utilized in various parts of Spanish America. African slave labor was introduced in the early Caribbean during the demographic collapse of the indigenous populations. The slave trade was in the hands of the Portuguese, who had an early monopoly on the coastal routes in Africa. Africans learned skilled trades and functioned as artisans in cities and labor bosses over indigenous in the countryside. Studies of the African slave trade and the economic role of blacks in Spanish America have increased, particularly with the development of Atlantic history. Asian slaves in Spanish America have been less well studied, but monograph on Mexico indicates the promise of this topic.[271] One of the few women to achieve fame in colonial Mexico was Catarina de San Juan, a slave in seventeenth-century Puebla.

The mobilization of indigenous labor in the Andes via the mita for the extraction of silver has been studied.[272][273][274] Encomienda or repartimiento labor was not an option in Mexico’s north; the workforce was of free laborers, who initially migrated from elsewhere to the mining zone.

Silver

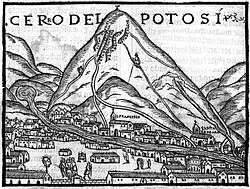

The major motor of the Spanish colonial economy was silver mining, which produced in upper Peru (now Bolivia) at the single site of production, Potosí. There were multiple sites in Mexico, mainly in the north outside the zone of dense indigenous population, which initially necessitated pacification of the indigenous populations to secure the mining sites and the north-south transportation routes.[275]

Silver and silver mining have occupied an important place in the history of Spanish America and the Spanish empire, since the two major sources of silver were found in the viceroyalties of New Spain (Mexico) and Peru, where there were significant numbers of indigenous and Spanish colonists.[276] The impact of silver on the world economy was profound in both Europe and Asia.[277][278] An early twentieth-century study dealing with the impact of colonial silver on Spain is Earl Hamilton”s. American Treasure and the Price Revolution in Spain.[279] Extensive work on the royal treasury by Herbert S. Klein and John Tepaske on colonial Spanish American and Spain is The Royal Treasuries of the Spanish Empire in America (3 vols.)[280] Other important publications on economic history include the comparison of New Spain and Peru,[281] and on price history.[282] Mercury was a key component to the process of extracting silver from ore. Mercury for Mexican mining production was shipped from the Almadén mine in Spain, while mercury production in Peru was from the mine at Huancavelica.[283][284]

Other commodity production

For a number of years scholars deeply researched landed estates, haciendas, and debated whether haciendas were feudal or capitalist and how they contributed to the economic development.[285][286] More recently, scholars have focused on commodity chains and their contribution to globalization, rather than focusing solely on production sites.[287]

Sugar as a commodity was cultivated from the earliest colonization in the Caribbean[288] and brought to Mexico by Hernán Cortés, which supplied domestic demand.[289] There is a vast literature about sugar plantations in various regions of Spanish America and Brazil.[290] Another tropical export product was cacao, which was grown in Mesoamerica. Once Europeans developed a taste for chocolate, with the addition of sugar, cacao production expanded.[291]

The production of mind-altering commodities was an important source of profit for entrepreneurs and the Spanish administration. Tobacco as a commodity was especially important in the late eighteenth century when the crown created a monopoly on its production and processing.[292][293][294] Demand by the urban poor for local production of pulque, the fermented alcohol from agave cacti, made it profitable, so that large-scale cultivation, including by Jesuit landed estates, met demand; the crown regulated taverns where it was consumed.[295] Coca, the Andean plant now processed into cocaine, was grown and the unprocessed leaves consumed by indigenous particularly in mining areas. Production and distribution of coca became big business, with non-indigenous owners of production sites, speculators, and merchants, but consumers consisting of indigenous male miners and local indigenous women sellers. The church benefited from coca production since it was by far the most valuable agricultural product and contributor to the tithe.[296]

Most high quality textiles were imported from Europe via the transatlantic trade controlled by Iberian merchants, but Mexico briefly produced silk.[297] As demand for cheap textiles grew, production for a growing local mass market took place in small-scale textile workshops (obrajes), which had low capital inputs, since the expansion of sheep ranching provided a local supply of wool, and low labor costs, with obrajes functioning in some cases as jails.[298] Spanish America is most noted for producing dyes for European textile production, in particular the red dye cochineal, made from the crushed bodies of insects that grew on nopal cactuses, and indigo. Cochineal was for Mexico its second most important export after silver, and the mechanisms to engage indigenous in Oaxaca involved crown officials and urban merchants.[299] The blue dye indigo was another important export, particularly from Central America.[300][301]

Trade routes and transportation

Crown policy attempted to control overseas trade, setting up the Casa de Contratación in 1503 to register cargoes including immigration to the overseas empire. From Spain, sailings to the major ports in Spanish America left from Seville. It was a distance up from the mouth of the Guadalquivir river, and its channel did not allow the largest transoceanic ships to dock there when fully loaded.

The Carrera de Indias was the main route of Spain’s Atlantic trade, originating in Seville and sailing to a few Spanish American ports in the Caribbean, particularly Santo Domingo, Veracruz, on the Atlantic coast of Panama, Nombre de Dios later Porto Bello. Since trade and commerce were so integral to the rise of Spain’s power, historians undertook studies of the policies and patterns.[302][303][304][305] J.H. Parry's classic The Spanish Seaborne Empire remains important for its clear explication of transatlantic trade, including ports, ships and ship building,[306] and there is new work on Spanish politics and trade with information on the fleets.[307]

Transatlantic trading companies based in Spain and with partners, usually other family members, established businesses to ship a variety of goods, sourced in Spain and elsewhere in Europe and shipped to the major ports of the overseas empire. The most important export from the New World was silver, which became essential for financing the Spanish crown and as other European powers became emboldened, the ships were targeted for their cargo. The system of convoys or fleets (Spanish: flota) was established early on, with ships from Veracruz and from South America meeting in the Caribbean for a combined sailing to Spain. Transpacific trade with the Spanish archipelago of the Philippines was established, with Asian goods shipped from Manila to the port of Acapulco. The Manila galleon brought silks, porcelains, and slaves to Mexico while Spanish silver was sent to Asia. The transpacific trade has been long neglected in comparison to the transatlantic trade and the rise of Atlantic history.[308][309] New works indicate that interest is increasing.[310][311][312]

Overland transportation of goods in Spanish America was generally by pack animals, especially mules, and in the Andean area llamas as well. But the Spanish did not build many roads allowing cart or carriage transport. Transit over oceans or coastal sailing was relatively efficient compared to land transportation, and in most places in Spanish America there were few navigable rivers and no possibility of canal construction. Transportation costs and inefficiency were drags on economic development; the problem was not overcome until railroads were constructed in the late nineteenth century. For bulky, low value foodstuffs, local supply was a necessity, which stimulated regional development of landed estates, particularly near mines.[313] Despite the inefficiencies overland trade, hubs of trade had main routes develop between them, with smaller communities linked by secondary or tertiary roads. The ability to move silver from remote mining regions to ports was a priority, and the supplies to mines of mercury was essential.[314]

Environmental impacts

The environmental impact of economic activity has coalesced as a field in the late twentieth century, in particular Alfred Crosby’s work on the Columbian Exchange and “ecological imperialism.”[315][316] Also important for environmental history is Elinor G.K. Melville’s work on sheep grazing and ecological change in Mexico.[317] For the Andean region, the ecological and human costs of mercury mining, essential to silver production, have recently been studied.[318]

Further reading

- Altman, Ida "The Revolt of Enriquillo and the Historiography of Early Spanish America," The Americas vol. 63(4)2007, 587-614

- Bowser, Frederick. "The African in Colonial Spanish America: Reflections on Research Achievements and Priorities," Latin American Research Review, vol. 7, no. 1 (Spring 1972), pp. 77–94.

- Brading, D.A. The First America: The Spanish Monarchy, Creole Patriots, and the Liberal State, 1492-1867. New York: Cambridge University Press 1991.

- Burkholder, Mark and Lyman L. Johnson. Colonial Latin America 9th edition. New York: Oxford University Press 2014.

- Cañizares-Esguerra, Jorge, How to Write the History of the New World: Histories, Epistemologies, and Identities in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic World. Stanford: Stanford University Press 2001.

- Carmagnani, Marcello, "The Inertia of Clio: The Social History of Colonial Mexico." Latin American Research Review vol. 20, No. 1 1985, 149-166.

- Cline, Howard F., ed. Latin American History: Essays on Its Study and Teaching, 1898-1965. 2 vols. Austin: University of Texas Press 1967.

- Delpar, Helen. Looking South: The Evolution of Latin Americanist Scholarship in the United States. University of Alabama Press 2007.

- Gibson, Charles, "Writings on Colonial Mexico," Hispanic American Historical Review 55:2(1975).

- Hispanic American Historical Review, Special issue: Mexico's New Cultural History: Una Lucha Libre. Vol. 79, No. 2, May, 1999

- Lockhart, James, "The Social History of Colonial Spanish America: Evolution and Potential". Latin American Research Review vol. 7, No. 1 (Spring 1972) 6-45.

- Lockhart, James and Stuart B. Schwartz, Early Latin American History. New York: Cambridge University Press 1983.

- Restall, Matthew, "A History of the New Philology and the New Philology in History", Latin American Research Review - Volume 38, Number 1, 2003, pp. 113–134

- Sauer, Carl O. The Early Spanish Main. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 1966, 1992.

- Schroeder, Susan and Stafford Poole, eds. Religion in New Spain. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 2007.

- Spalding, Karen. "The Colonial Indian: Past and Future Research Perspectives," Latin American Research Review, Vol. 7, No. 1 (Spring 1972), 47-76.

- Stern, Steve J. "Paradigms of Conquest: History, Historiography, and Politics," Journal of Latin American Studies 24, Quincentenary Supplement (1992):1-34.

- Twinam, Ann, Purchasing Whiteness: Pardos, Mulattos, and the Quest for Social Mobility in the Spanish Indies. Stanford: Stanford University Press 2015.

- Van Young, Eric, "Mexican Rural History Since Chevalier: The Historiography of the Colonial Hacienda," Latin American Research Review, 18 (3) 1983; 5-61.

- Van Young, Eric, "Recent Anglophone Historiography on Mexico and Central America in the Age of Revolution (1750-1850)," Hispanic American Historical Review, 65 (1985): 725-743.

See also

- Spanish empire

- Spanish American Enlightenment

- Bourbon Reforms

- New Spain

- History of Mexico

- Economic history of Mexico

- History of Roman Catholicism in Mexico

- New Philology

- Latin American studies

References

- ↑ See the volumes of Handbook of Middle American Indians (HMAI), Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources. 4 vols. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1972 for a compendium of early modern sources and histories.

- ↑ J. Benedict Warren, "An Introductory Survey of Secular Writings in the European Tradition on Colonial Middle America, 1503-1818." HMAI vol. 13, pp. 42-137.

- ↑ Ernest J. Burrus, S.J. "Religious Chroniclers and Historians: A Summary with Annotated Bibliography." HMAI vol. 13, pp. 138-186

- ↑ Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra, How to Write the History of the New World: Histories, Epistemologies, and Identities in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic World. Stanford: Stanford University Press 2001.

- ↑ D.A. Brading, The First America: The Spanish Monarchy, Creole Patriots, and the Liberal State, 1492-1867. New York: Cambridge University Press 1991.

- ↑ see Lucas Alamán, Historia de Mejico. 5 vols.

- ↑ William H. Prescott, History of the Conquest of Mexico (1843) and History of the Conquest of Peru (1847), which have gone through multiple editions.

- ↑ Edward Gaylord Bourne, Spain in America, 1450-1580. 4 vols. A new edition with a new introduction and supplementary bibliography was published in 1962. New York: Barnes & Noble.

- ↑ Herbert Eugene Bolton, "The Epic of Greater America," American Historical Review 38-448-474 (April 1933), presidential address.

- ↑ Howard F. Cline, "Latin American History: Development of Its Study and Teaching in the United States Since 1898," in Latin American History: Essays on Its Study and Teaching, 1898-1965. Howard F. Cline, ed. Austin: University of Texas Press 1967, pp. 6-16.

- ↑ J. Franklin Jameson, "A New American Historical Journal", Hispanic American Historical Review 1:2-7 (Feb. 1918).

- ↑ New York: Harper & Row 1966.

- ↑ James Lockhart and Stuart B. Schwartz, Early Latin America: A History of Colonial Spanish America and Brazil. New York: Cambridge University Press 1983.

- ↑ P.J. Bakewell, A History of Latin America to 1825. Malden MA: Wiley-Blackwell 2010.

- ↑ Mark Burkholder and Lyman R. Johnson, Colonial Latin America 9th edition. New York: Oxford University Press 2014.

- ↑ James Lockhart and Enrique Otte, Letters and People of the Indies: Sixteenth Century. New York: Cambridge University Press 1976.

- ↑ Kenneth Mills and William B. Taylor, eds. Colonial Spanish America: A Documentary History. Lanham MD: SR Books 1998.

- ↑ Kenneth Mills, William B. Taylor, and Sandra Lauderdale Graham, Colonial Latin America: A Documentary History. Lanham MD: SR Books 2002.

- ↑ Richard Boyer and Geoffrey Spurling, Colonial Lives: Documents on Latin American History, 1550-1850. New York: Oxford University Press 1999.

- ↑ Michael C. Meyer, William Sherman, and Susan Deeds, The Course of Mexican History. 10th edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013. There is a significant portion of it on colonial history.

- ↑ Michael C. Meyer and William H. Beezley, The Oxford History of Mexico. New York: Oxford University Press 2000.

- ↑ William H. Beezley, A Companion to Mexican History and Culture. Malden MA: Wiley-Blackwell 2011.

- ↑ Ida Altman, Sarah Cline & Juan Javier Pescador, The Early History of Greater Mexico. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2003

- ↑ Alan Knight, Mexico: The Colonial Era, 1540-1810, New York: Cambridge University Press 2002.

- ↑ José C. Moya, The Oxford Handbook of Latin American History, New York: Oxford University Press 2011. The essays are historiographical.

- ↑ Kevin Terraciano and Lisa Sousa, "Historiography of New Spain," Oxford Handbook, pp. 25-64.

- ↑ Lynman L. Johnson and Susan M. Socolow, "Colonial Spanish America", Oxford Handbook, pp. 65-97

- ↑ Asunción Lavrin "Sexuality in Colonial Spanish America", Oxford Handbook, pp. 132-152.

- ↑ Jeremy Adelman, "Independence in Latin America" in Oxford Handbook, pp. 153-180.

- ↑ Charles Gibson and Benjamin Keen, "Trends of United States Studies in Latin American History," American Historical Review, LXII (July 1957),

- ↑ Charles Gibson, "Writings on Colonial Mexico," Hispanic American Historical Review 55:2(1975).

- ↑ Eric Van Young, "Recent Anglophone Historiography on Mexico and Central America in the Age of Revolution (1750-1850)," Hispanic American Historical Review, 65 (1985): 725-743.

- ↑ J. Benedict Warren, "An Introductory Survey of Secular Writings in the European Tradition on Colonial Middle America, 1503-1818." Handbook of Middle American Indians vol. 13, pp. 42-137.

- ↑ Ernest J. Burrus, S.J. "Religious Chroniclers and Historians: A Summary with Annotated Bibliography." Handbook of Middle American Indians vol. 13, pp. 138-186

- ↑ David Brading, The First America: The Spanish Monarchy, Creole Patriots, and the Liberal State, 1492-1867. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1991.

- ↑ Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra, How to Write the History of the New World: Histories, Epistemologies, and Identities in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic World. Stanford: Stanford University Press 2001.

- ↑ William S. Maltby, The Black Legend in England: The Development of Anti-Spanish Sentiment, 1558-1660. Durham: Duke University Press 1971.

- ↑ Benjamin Keen, "The Black Legend Revisited: Assumptions and Realities," Hispanic American Historical Review, 49:4(1969) 703-719.

- ↑ Lewis Hanke, Aristotle and the American Indians (1959), and the Spanish Struggle for Justice

- ↑ Lewis Hanke, "A Modest Proposal for a Moratorium on Grand Generalizations," Hispanic American Historical Review 51:1(1971)112-127.

- ↑ Benjamin Keen, "The White Legend Revisited," Hispanic American Historical Review 51(2)(1971) 336-355.

- ↑ Margaret R. Greer and Walter Mignolo, eds. (2007). Rereading the Black Legend: The Discourses of Religious and Racial Difference in the Renaissance Empires. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 2007.

- ↑ Brading, The First America, pp. 432-441.

- ↑ Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra, How to Write the History of the New World pp. 171-182.

- ↑ Brading, The First America.

- ↑ Cañizares-Esguerra, How to Write the History of the New World.

- ↑ D.A. Brading, "Scientific Traveller", chapter 23 in The First America, pp. 514-534

- ↑ http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/85270#page/8/mode/1up Essai politique sur le royaume de la Nouvelle Espagne] (1811); English translation: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/85282#page/12/mode/1up Political essay on the kingdom of New Spain containing researches relative to the geography of Mexico], (1811) biodiversitylibrary.org

- ↑ Brading, The First America, p. 517.

- ↑ Lucas Alamán, Historia de Mejico. 5 vols. 1849-52

- ↑ "Vicente Riva Palacio" in Encyclopedia of Mexico. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, p. 1282.

- ↑ Vicente Riva Palacio, ‘’México á través de los siglos Historia general y completa del desenvolvimiento social, político, religioso, militar, artístico, científico y literario de México desde la antigüedad más remota hasta la época actual ... ’’ Barcelona: Espasa y Compañía 1888-89.

- ↑ Justo Sierra, The Political Evolution of the Mexican People. Austin: University of Texas Press 1969.

- ↑ Robin A. Humphreys, "William Hickling Prescott: The Man and the Historian". Hispanic American Historical Review 39:1-19 (Feb. 1959)

- ↑ Brading, The First America, pp. 633-34.

- ↑ Howard F. Cline, "Imperial Perspectives on the Borderlands", in Latin American History: Essays on Its Study and Teaching, 1898-1965, vol. 1, pp. 224-227. Austin: University of Texas Press 1967.

- ↑ Howard F. Cline, "Hubert Howe Bancroft, 1832-1918" in Handbook of Middle American Indians vol. 13, pp. 326-347.

- ↑ Howard F. Cline, "Latin American History: Development of Its Study and Teaching in the United States Since 1898," Latin American History: Essays on Its Study and Teaching. Austin: University of Texas Press 1967, p.7.

- ↑ H.E. Bolton, "The Epic of Greater America". The American Historical Review, 38:448-474 (April 1933).

- ↑ Howard F. Cline, ed. Latin American History: Essays on Its Study and Teaching, 1898-1965. 2 vols. Austin: University of Texas Press 1967.

- ↑ Helen Delpar, Looking South: The Evolution of Latin Americanist Scholarship in the United States, 1850-1975. University of Alabama Press 2007.

- ↑ Victor Bulmer-Thomas, Thirty Years of Latin American Studies in the United Kingdom 1965-1995. London: Institute of Latin American Studies, 1997.

- ↑ J.H. Parry The Age of Reconnaissance. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 1981..

- ↑ William D. Phillips and Carla Rahn Phillips, The Worlds of Christopher Columbus. New York: Cambridge University Press 1992.

- ↑ Troy S. Floyd, The Columbus Dynasty in the Caribbean, 1492-1526. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 1973.

- ↑ Carl O. Sauer, The Early Spanish Main. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 1966, 1992.

- ↑ Samuel M. Wilson, Hispaniola, Caribbean Chiefdoms in the Age of Columbus. Tuscoloosa: University of Alabama Press 1990.

- ↑ Ida Altman, "The Revolt of Enriquillo and the Historiography of Early Spanish America," The Americas vol. 63(4)2007, 587-614

- ↑ Steve J. Stern, "Paradigms of Conquest: History, Historiography, and Politics," Journal of Latin American Studies 24, Quincentenary Supplement (1992):1-34.

- ↑ Ida Altman, Sarah Cline, and Javier Pescador, "Narratives of Conquest" in The Early History of Greater Mexico. Prentice Hall 2003, pp. 97-114.

- ↑ Bernardino de Sahagún, Florentine Codex, Book XII. Arthur J.O. Anderson and Charles Dibble, translators and editors. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press 1975.

- ↑ Bernardino de Sahagún, The Conquest of New Spain, 1585 Revision, Howard F. Cline and Sarah Cline, editors and translators. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press 1989.

- ↑ S.L. Cline, "Revisionist Conquest History: Sahagún's Book XII," in The Work of Bernardino de Sahagún: Pioneer Ethnographer of Sixteenth-Century Aztec Mexico. Ed. Jorge Klor de Alva et al. Institute for Mesoamerican Studies, Studies on Culture and Society, vol. 2, 93-106. Albany: State University of New York, 1988.

- ↑ Miguel León-Portilla, ed. The Broken Spears. 3rd ed. Boston: Beacon Press 2007,

- ↑ Stuart B.Schwartz, Victors and Vanquished: Spanish and Nahua Views of the Conquest of Mexico. Boston: Bedford/St Martin's Press 2000.

- ↑ James Lockhart, editor & translator, We People Here: Nahuatl Accounts of the Conquest of Mexico. Los Angeles: UCLA Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, University of California Press 1993.

- ↑ Matthew Restall, ‘’Maya Conquistador’’ Boston: Beacon Press 1998.

- ↑ Matthew Restall, "The New Conquest History," History Compass, vol 10, Feb. 2012.

- ↑ Sherburne F. Cook and Woodrow Borah, Essays in Population History 3 vols. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 1971-1979.

- ↑ David P. Henige, Numbers from Nowhere: the American Indian Contact Population Debate, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 1998.

- ↑ Nobel David Cook, Born to Die: Disease and New World Conquest, 1492-1650. New York: Cambridge University Press 1998.

- ↑ Noble David Cook and W. George Lovell, eds. The Secret Judgments of God: Old World Disease in Colonial Spanish America. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 1992.

- ↑ Donald B. Cooper, Epidemic Disease in Mexico City, 1761-1813: An Administrative, Social, and Medical Study. Austin: University of Texas Press 1965.

- ↑ Pamela Voekel, Alone Before God: The Religious Origins of Modernity in Mexico, chapter 7 “The Rise of Medical Empiricism”. Durham: Duke University Press 2002.

- ↑ Martha Few, For All Humanity: Mesoamerican and Colonial Medicine in Enlightenment Guatemala. Tucson: University of Arizona Press 2015.

- ↑ Charles Gibson and Benjamin Keen, "Trends of United States Studies in Latin American History," The American Historical Review, LXII (July 1957), 857

- ↑ Clarence Haring, Trade and Navigation between Spain and the Indies in the Time of the Hapsburgs. Cambridge MA: Harvard Economic Studies 1918.

- ↑ Clarence Haring, The Spanish Empire in America New York: Oxford University Press 1947.

- ↑ Lillian Estelle Fisher, Viceregal Administration in the Spanish American Colonies. Berkeley: University of California Press 1926

- ↑ Lillian Estelle Fisher, The Intendant System in Spanish America, Berkeley: University of California Press 1919.

- ↑ Arthur S. Aiton, Antonio de Mendoza, First Viceroy of New Spain. Durham: Duke University Press 1927.

- ↑ J.H. Parry, The Audiencia of New Galicia in the Sixteeth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1948.

- ↑ J.H. Parry, The Sale of Public Office in the Spanish Indies under the Hapsburgs. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 1953.

- ↑ John Leddy Phelan, "Authority and Flexibility in the Spanish Imperial Bureaucracy," Administrative Science Quarterly 5:1 (1960): 47-65.

- ↑ Woodrow Borah, Justice by Insurance: The General Indian Court of Colonial Mexico and the Legal Aides of the Half-real. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 1983

- ↑ in A Companion to Latin American History, Thomas H. Holloway, ed. Malden MA: Wiley-Blackwell 2011, pp.106-123.

- ↑ Robert Ricard, The Spiritual Conquest of Mexico: An Essay in the Apostolate and the Evangelizing Methods of the Mendicant Orders in New Spain, 1523-1572ear. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 1966. Originally published in French 1933.

- ↑ John Leddy Phelan, The Millennial Kingdom of the Franciscans in the New World: A Study in the Writings of Gerónimo de Mendieta. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 1956.

- ↑ Henry Charles Lea, The Inquisition in the Spanish Dependencies. New York: MacMillan 1908.

- ↑ Richard E. Greenleaf, The Inquisition in Sixteenth-Century Mexico. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 1963.

- ↑ Jacques A. Barbier, Reform and Politics in Bourbon Chile, 1755-1796. Ottawa 1980

- ↑ J.R. Fisher, Government and Society in Colonial Peru: The Intendant System, 1784-1814. London: Athlone 1970.

- ↑ John Fisher, "Imperial Rivalries and Reforms" in A Companion to Latin American History, Thomas H. Holloway, ed. Malden MA: Wiley-Blackwell 2011, pp. 178-194.

- ↑ N.M. Farriss, Crown and Clergy in Colonial Mexico, 1759-1821. London: Athlone 1968.

- ↑ Pamela Voekel, Alone Before God: The Religious Origins of Modernity in Mexico. Durham: Duke University Press 2002.

- ↑ John R. Fisher, "Imperial ‘Free Trade’ and the Hispanic Economy, 1778-1796," Journal of Latin American Studies 13 (1981): 21-56.

- ↑ John R. Fisher, Commercial Relations between Spain and Spanish America in the Era of Free Trade, 1778-1796. Liverpool: University of Liverpool, Centre for Latin American Studies 1985.

- ↑ Brian R. Hamnett, Politics and Trade in Southern Mexico, 1750-1821. New York: Cambridge University Press 1971.

- ↑ Jeremy Baskes, Indians, Merchants, and Markets: A reinterpretation of the Repartimiento and Spanish-Indian Economic Relations in Colonial Oaxaca, 1750-1821. Stanford: Stanford University Press 2000.

- ↑ Lyle N. McAlister, The "Fuero Militar" in New Spain, 1764-1800. Gainesville: University of Florida Press 1957.

- ↑ Christon I. Archer, The Army in Bourbon Mexico, 1760-1810, Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 1977.

- ↑ Leon G. Campbell, The Military and Society in Colonial Peru, 1750-1810. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press 1978.

- ↑ Allan J. Kuethe, Military Reform and Society in New Granada, 1773-1808. Gainesville: University of Florida Press 1978.

- ↑ Ben Vinson III, Bearing Arms for His Majesty: The Free Colored Militia in Colonial Mexico. Stanford: Stanford University Press 2001.

- ↑ James Lockhart, "The Social History of Colonial Spanish America: Evolution and Potential". Latin American Research Review vol. 7, No. 1 (Spring 1972), p. 6, revised, 1999 in Of Things of the Indies: Essays Old and New in Early Latin American History, Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp. 27-80.

- ↑ Fred Bronner, "Urban Society in Colonial Spanish America: Research Trends," Latin American Research Review vol. 21, No. 1 (1986), p. 50.

- ↑ James Lockhart, Spanish Peru. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press 1968, revised 1994).

- ↑ James Lockhart, The Men of Cajamarca Austin: University of Texas Press 1972.

- ↑ Robert Himmerich y Valenica, The Encomenderos of New Spain, 1521-1555. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1991.

- ↑ Ana María Presta, Encomienda, familia y negocios en Charcas Colonial: Los encomenderos de La Plata. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos 2000.

- ↑ José de la Puente Brunke, Encomienda y encomenderos en el Perú. Seville: Deputación de Sevilla 1992.

- ↑ José Ignacio Avellaneda, The Conquerors of the New Kingdom of Granada. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 1996.

- ↑ Frances Karttunen, "Rethinking Malinche," in Indian Women of Early Mexico. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 1997.

- ↑ Camilla Townsend, Malintzin's Choices: An Indian Woman in the Conquest of Mexico. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 2006.

- ↑ Karen Powers, Women in the Crucible of the Conquest. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 2005

- ↑ Matthew Restall, "Black Conquistadors: Armed Africans in Early Spanish America," The Americas 57:2(2000)171-205.

- ↑ Matthew Restall, Maya Conquistador. Boston: Beacon Press 1998.

- ↑ Magnus Morner, "Economic Factors and Stratification in Colonial Spanish America with Special Regard to Elites," Hispanic American Historical Review 63, no. 2 1983: 335-69

- ↑ John Kicza, "Elites in New Spain," Latin American Research Review vol.21(2) 1986, pp. 189-196.

- ↑ Fred Bronner, "Urban Society in Colonial Spanish America: Research Trends," Latin American Research Review vol. 21, no. 1 1986, 7-72.

- ↑ David Brading, Miners and Merchants in Bourbon Mexico, 1763-1810. New York: Cambridge University Press 1971.

- ↑ Peter J. Bakewell, Silver and Society in Zacatecas, New York: Cambridge University Press 1971.

- ↑ Lousia Schell Hoberman, "Merchants in Seventeenth-Century Mexico City: A Preliminary Portrait," Hispanic American Historical Review 57 (1977): 479-503.

- ↑ Louisa Schell Hoberman, Mexico's Merchant Elite: 1590-1660: Silver, State, and Society. Durham: Duke University Press 1991.

- ↑ John Kicza, Colonial Entrepreneurs: Families and Business in Bourbon Mexico City. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 1983.

- ↑ Jackie R. Booker, Veracruz Merchants, 1770-1829: A Mercantile Elite in Late Bourbon and Early Independent Mexico. Boulder: Westview Press 1993.

- ↑ Susan Migden Socolow, The Merchants of Buenos Aires, 1778-1810.

- ↑ Ann Twinam, Miners, Merchants, and Farmers in Colonial Colombia . Austin: University of Texas Press 1982.

- ↑ Francisco Morales, Ethnic and Social Background of the Franciscan Friars in Seventeenth-Century Mexico. Washington DC: Academy of American Franciscan History 1973.

- ↑ William B. Taylor, Magistrates of the Sacred: Priests and Parishioners in Eighteenth-Century Mexico. Stanford: Stanford University Press 1996.

- ↑ Paul Ganster, "A social history of the secular clergy of Lima during the middle decades of the eighteenth century," Ph.D. dissertation, UCLA 1989.

- ↑ Howard F. Cline, ed. Handbook of Middle American Indians, Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources, Vols. 12-15. Austin: University of Texas Press 1972-1975.

- ↑ Charles Gibson, Tlaxcala in the Sixteenth Century. New Haven: Yale University Press 1952.

- ↑ Charles Gibson, The Aztecs Under Spanish Rule. Stanford: Stanford University Press 1964.

- ↑ Woodrow W.Borah, ‘’Justice by Insurance’’.

- ↑ Gibson, The Aztecs Under Spanish Rule.

- ↑ James Lockhart, The Nahuas After the Conquest. Stanford: Stanford University Press 1992.

- ↑ Matthew Restall, "A History of the New Philology and the New Philology in History", Latin American Research Review Volume 38, Number 1, 2003, pp.113–134

- ↑ Karen Spalding, "The Colonial Indian: Past and Future Research Perspectives." Latin American Research Review, vol. 7, no. 1 (Spring 1972), pp. 47-76.

- ↑ Karen Spalding, Huarochiri: an Andean Society Under Inca and Spanish Rule. Stanford: Stanford University Press 1984

- ↑ Steve J. Stern, Peru's Indian Peoples and theChallenge of the Spanish Conquest: Huamanga to 1640. 1982.

- ↑ Susan E. Ramírez, The World Upside Down: Cross-Cultural Contact and Conflict in Sixteenth Century Peru. Stanford: Stanford University Press 1996.

- ↑ Ida Altman, The War for Mexico's West: Indians and Spaniards in New Galicia, 1524-1550. Albuquerque: New Mexico, 2010.

- ↑ William B. Taylor, Drinking, Homicide, and Rebellion in Colonial Mexican Villages'. Stanford: Stanford University Press 1979.

- ↑ Victoria Reiff Bricker, The Indian Christ, the Indian King: The Historical Substrate of Maya Myth and Ritual. Austin: University of Texas Press 1981.

- ↑ Kevin Gosner, Soldiers of the Virgin: The Moral Economy of a Colonial Maya Rebellion. Tucson: University of Arizona Press 1992.

- ↑ Charlotte M. Gradie, The Tepehuan Revolt of 1616: Militarism, Evangelism and Colonialism in Seventeenth-Century Nueva Vizcaya. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press 2000.

- ↑ Rolena Adorno, Guaman Poma: Writing and Resistance in Colonial Peru. Austin: University of Texas Press 1988.

- ↑ Steve J. Stern, ed. Resistance, Rebellion, and Consciousness in the Andean Peasant World, 18th to 20th centuries. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press 1987.

- ↑ Scarlett O’Phelan Godoy, Rebellions and Revolts in Eighteenth-Century Peru and Upper Peru. Vienna: Bohlau Verlag 1985.

- ↑ Charles F. Walker, The Tupac Amaru Rebellion . Cambridge: Harvard University Press 2014.

- ↑ Charles F. Walker, Smoldering Ashes: Cuzco and the Creation of Republican Peru, 1780-1840. Durham: Duke University Press.

- ↑ Leon G. Campbell, "The Army of Peru and the Tupac Amaru Revolt: 1780-1783". Hispanic American Historical Review 56:1(1976) 31-57.

- ↑ Ward Stavig, The World of Tupac Amaru: Conflict, Community, and Identity in Colonial Peru. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 1999.

- ↑ Gonzalo Aguirre Beltrán, La población negra de México, 1519-1810: Estudio etnohistórico. Mexico City: Fuente Cultural 1946.1946

- ↑ Frank Tannenbaum, Slave and Citizen: The Negro in the Americas. New York: Vintage Books 1947.

- ↑ Alejandro de la Fuente, “Slave, Law, and Claims-Making in Cuba: The Tannenbaum Debate Revisited,” ‘’Law and History Review‘’ 22, no. 2 (July 2004), 383-87.

- ↑ Magnus Mörner, Race Mixture in the History of Latin America. Boston: Little Brown 1967.

- ↑ Frederick Bowser, The African Slave in Colonial Peru, 1524-1650. Stanford: Stanford University Press 1974,

- ↑ Bowser, Frederick. "The African in Colonial Spanish America: Reflections on Research Achievements and Priorities," Latin American Research Review, vol. 7, no. 1 (Spring 1972), pp. 77–94.

- ↑ John K. Chance and William B. Taylor, "Estate and Class in a Colonial City: Oaxaca in 1792," Comparative Studies in Society and History, 19:4 (October 1977), pp. 454-87

- ↑ Robert McCaa, Stuart B. Schwartz, and Arturo Grubessich, "Race and Class in Colonial Latin America: A Critique," Comparative Studies in Society and History 21:3 (July 1979), pp. 421- 433

- ↑ Patricia Seed, "Social Dimensions of Race: Mexico City 1753," Hispanic American Historical Review 62(4)1982, 569-606.

- ↑ Patricia Seed, Philip F. Rust, Robert McCaa and Stuart B. Schwartz, "Measuring Marriage by Estate and Class: A Debate," Comparative Studies in Society and History 25:4 (October 1983), pp. 703-723

- ↑ Bruce Castleman, "Social Climbers in a Colonial Mexican City: Individual Mobility within the Sistema de Castas in Orizaba, 1777-1791," Colonial Latin American Review 10:2 (December 2001) 229-49.

- ↑ Aaron P. Althouse, "Contested Mestizos, Alleged Mulattos: Racial Identity and Caste Hierarchy in Eighteenth-Century Pátzcuaro, Mexico," The Americas Vol. 62, No. 2 (Oct., 2005), pp. 151-175

- ↑ María Concepción García Sáiz, Las castas mexicanas: Un género pictórico americano. Milan: Olivetti 1989.

- ↑ Ilona Katzew, Casta Painting: Images of Race in Eighteenth-Century Mexico. New Haven: Yale University Press 2004.

- ↑ Sarah Cline, "Guadalupe and the Castas: The Power of a Singular Colonial Mexican Painting," Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos vol. 31 (2) summer 2015, 218-247., analyzes the only known casta painting with an overt religious theme.

- ↑ María Elena Martínez, Genealogical Fictions: Limpieza de Sangre, Religion, and Gender in Colonial Mexico. Stanford: Stanford University Press 2008

- ↑ Ann Twinam, Purchasing Whiteness: Pardos, Mulattos, and the Quest for Social Mobility in the Spanish Indies. Stanford: Stanford University Press 2015.

- ↑ R. Douglas Cope, The Limits of Racial Domination: Plebeian Society in Colonial Mexico, 1660-1720. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press 1994.

- ↑ Susan Schroeder, "Jesuits, Nahuas, and the Good Death Society in Mexico City, 1710-1767," Hispanic American Historical Review 80, no. 1 (2000), 43-76.

- ↑ Nicole von Germeten, Black Blood Brothers: Confraternities and Social Mobility for Afro-Mexcians. Gainesville: University of Florida Press 2006.

- ↑ Karen B. Graubart, “So Color de una Cofradía: Catholic Confraternities and the Development of Afro-Peruvian Ethnicities in Early Colonial Peru,” Slavery & Abolition 33 , no. 1 (2012), 43-64.

- ↑ Matthew Restall, ed. Beyond Black and Red: African-Native Relations in Colonial Yucatan. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 2005.