High-speed railway to Eilat

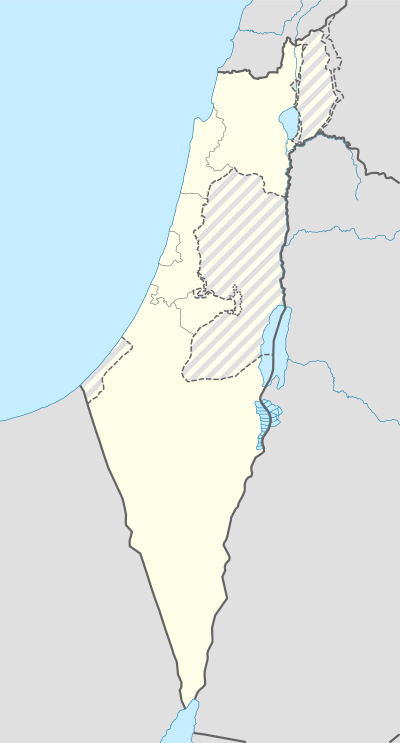

The High-speed railway to Eilat (Med-Red)[1] is a proposed Israeli railway that will enable the connection of the main Israeli population centers and Mediterranean ports to the southern city of Eilat on the Red Sea coast, as well as serve commercial freight between the Mediterranean Sea (city of Ashdod) and Red Sea (Eilat). The railway will spur southward from the existing rail line at Beersheba, and continue through Dimona to the Arava, Ramon Airport and Eilat, at a speed of 350 kilometers per hour (220 mph).[1] Its length will be roughly 260 km of electrified double-track rail (not including the Tel Aviv – Beersheba section, an additional 100 km).

The railway, if built, is expected to serve both passengers and freight, including minerals mined from the Negev Desert. The high-speed passenger service will carry travelers from Tel Aviv to Eilat in two hours or less with one intermediate stop (at the Beersheba North Railway Station), and with a slower service offering from Beersheba to Eilat, stopping at a number of towns and villages in the Arava. The freight service will serve as an alternative to the Suez Canal, allowing countries in Asia to pass goods to Europe through Israel. The line is part of a greater plan to turn Eilat into a metropolitan area numbering 150,000 residents, as well as [1] relocating the Port of Eilat 5 km further inland.

In 2015, the financial newspaper Globes reported that if the project went ahead, it was likely that Chinese contractors would build the train line and infrastructure, and supply the trains and locomotives.[2]

History

Eilat is located far away from Israel's main population centers, yet serves as an important tourist city and has a strategic location as Israel's only access point to the Red Sea.[3][4] Historically it has been connected to the rest of the country with poor transportation infrastructure. Both roads to Eilat—Highway 90 and Road 12—have been the scenes of frequent traffic accidents and in some cases terrorist attacks, though in recent years these roads are finally being upgraded.

A line was planned after the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, but plans were cancelled in 1952 due to security concerns. In 1955, Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion again decided to build such a railway, and the French expressed interest in the project, just before the Suez Crisis. The idea was again discussed in the 1960s and 70s, and in the 1980s an Australian fund submitted a concrete proposal for funding the construction (at the time estimated at USD 250 million). The transportation minister Haim Corfu appointed a committee that recommended starting construction immediately. The government again turned to France to develop the railway. In the 1990s and 2000s, various transportation ministers, including Yisrael Keisar, Meir Sheetrit, Avigdor Lieberman and Shaul Mofaz, promised that such a railway would be built.[5]

In the 2010s the Israeli government approved the construction of a new port and airport for Eilat, a railway, upgraded highways and a light rail system.[6] The plan would see Eilat turn into a metropolitan area numbering 150,000 residents.[7] According to Israeli journalist Guy Bechor, the project would put Israel back on the global trade map.[8]

Planning and financing

The project is expected to cost NIS 6–8.6 billion, not including rolling stock, electrification and other related costs—which could be up to NIS 30 billion.[6][9][10] Initial planning will cost NIS 150 million and will come out of the Netivei Israel budget (Netivei Israel is a national program to build additional roads and railways).[11] It is estimated that the line would not directly return the investment cost.[5]

In October 2011, Israeli Minister of Transport Yisrael Katz signed a cooperation agreement regarding the railway with his Chinese counterpart.[12] In May 2012, Katz signed a similar agreement with Spain regarding general transportation development, which may involve the railway.[13] He also conducted talks on the subject with the Indian tourism minister.[14] In all, ten countries have taken interest in the project, with Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, South Korea and the United States being the other seven.[15]

On February 5, 2012, the Israeli cabinet unanimously approved continuing to pursue the project. There are three possible financing options: Build-operate-transfer, through an agreement with a foreign government, or complete funding by the Israeli government. Transport minister Katz put his support behind a partnership with a foreign government, and the Prime Minister's Office will have the final say.[9] The finance ministry opposes a deal with a foreign government without issuing a tender.[16]

A ministerial committee approved the plan in 2013.[17]

Route

The route to Eilat crosses hundreds of kilometers of rough desert terrain, with frequent elevation changes and the potential for flash floods. This is particularly challenging to high-speed railway construction whose aim is avoid sharp curves along the route. The topographically-challenging nature of the route (and consequently the large investment required) is one of the main reasons the railway hasn't been constructed to date, despite the frequently-expressed desire of various Israeli governments for such a line to be built.

The railway's proposed route can be divided into three parts: Beersheba–Dimona, Dimona – Mount Tzin and Mount Tzin – Eilat. The line would connect to the existing railway to Beersheba which is already double tracked and is planned for electrification but the existing railway between Dimona and Mount Tzin will need to be double-tracked, electrified and upgraded to allow a speed of up to 160 kilometers per hour (99 mph).[18] The project will feature 63 bridges spanning a total of 4.5 kilometers and 9.5 kilometers of tunnels.[19] Four more kilometers of tunnels may be built in the Mount Tzin area to further shorten the route and travel time.[18][20] Therefore, the railway will have separate tracks for passenger and freight traffic in the Mount Tzin area, where passenger trains will make use of the 4 km shortcut tunnel, while freight trains will use the longer, but more gradually inclining existing freight route.[21]

The Beersheba–Dimona section is 34 km (21 mi), the Dimona – Mount Tzin section is 54 km (34 mi) and the Arava section is about 170 km (110 mi).[18] The Arava section would run through the natural habitat of halocnemum strobilaceum, a desert plant thought to have been extinct, and was rediscovered in 2012.[22] The section from Dimona to Hatzeva and Paran through the Mount Tzin area was approved by the National Planning and Construction Committee on March 5, 2013.[23]

A preliminary plan envisioned nine stations in the Arava and Eilat section: from north to south, Hatzeva, Sapir, Paran, Yahel, Yotvata, Timna Airport, Shchoret, Eilat Center and the Port of Eilat.[24]

Technical and service specifications

The railway's route in the Arava will allow a maximum speed of 230 to 300 km/h (143 to 187 MPH). The line will be fully electrified and double tracked.[18]

The passenger service will feature an express and regular service options. The route is being planned such that travel on the express route from the Tel Aviv HaHagana Railway Station to Eilat will take two hours or less.[18] An estimated 3.5 million passengers will use the service every year.[24]

The freight service is expected to transport about 2.5 million tons of chemicals and 140,000 cars a year for the local market.[24] In addition to the local market, the railway will serve Asian countries that want to transport freight to Europe by serving as a land bridge from the Red to the Mediterranean sea; in that respect it will compete with the Suez Canal, although the Israel Port Authority and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu stated that it's not meant to compete on a regular basis.[9][25][26] According to Netanyahu, China and India have expressed interest in the project.[9] On the other hand, Egyptian officials have criticized the project as an alleged attempt to harm the Egyptian economy.[27]

References

- 1 2 3 "A High Speed Rail Connection for New Ports at Ashdod and Eilat". Econostrum.info.

- ↑ China to be Israel’s biggest infrastructure partner

- ↑ Dumper, Michael; Stanley, Bruce E. (2006). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa – A Historical Encyclopedia. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-57607-919-5. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

- ↑ "Elat". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

- 1 2 Hazelcorn, Shahar (February 2, 2012). "From Tel Aviv to Eilat, in Two Hours and 64 Years". Ynet (in Hebrew). Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- 1 2 Gil, Yasmin (July 18, 2011). "Is This What Will Save the City's Decline? The Prime Minister Assembled Ministerial Committee for Eilat Development". Calcalist (in Hebrew). Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- ↑ Neuman, Nadav (February 11, 2013). "Regional Committee Approves Tel Aviv-Eilat Railway Route". Globes. Retrieved February 11, 2013.

- ↑ Bechor, Guy (February 12, 2012). "From Bombay to Jerusalem" (in Hebrew). Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Keinon, Herb (February 5, 2012). "Cabinet Approves Red-Mel Rail Link". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- ↑ "Cabinet Unanimously Approves Eilat Railway". Globes. February 5, 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- ↑ "On Sunday, Tel Aviv – Eilat Line Will Be Brought Before Government for Approval". Port2Port. January 25, 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- ↑ Petersburg, Ofer (October 23, 2011). "Chinese to Build Railway to Eilat". Ynetnews. Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- ↑ Hazelcorn, Shahar (May 30, 2012). "Not Just China – Spain Also Wants to Build Railway to Eilat". Ynet (in Hebrew). Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- ↑ Blumenkranz, Zohar (June 25, 2012). "Katz: "In Three Years We Will Double the Number of Tourists Between India and Israel"". TheMarker (in Hebrew). Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ↑ Dar'el, Yael (August 2, 2012). "Transport Ministry in Contact with Ten Countries for Building Railway to Eilat". nrg Ma'ariv (in Hebrew). Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- ↑ Bassok, Moti; Schmil, Daniel (February 5, 2012). "Israeli Cabinet Approves Construction of High-Speed Train Line Between Tel Aviv and Eilat". Haaretz. Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- ↑ Israel approves controversial rail route to Eilat

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hazelcorn, Shahar (November 24, 2010). "Under Consideration: Railway to Eilat at 300 kmph". Ynet (in Hebrew). Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- ↑ "The Railway to Eilat Project Begins" (in Hebrew). Port2Port. November 23, 2010. Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- ↑ Gutman, Lior (January 9, 2012). "Scoop: Netanyahu Asked to Shorten Travel Time in the Future Line from Eilat to Tel Aviv to Two Hours". Calcalist (in Hebrew). Retrieved September 23, 2014.

- ↑ Hadar, Tomer (February 11, 2013). "Despite the Green Movements: Railway to Eilat Will Be Built Soon". Calcalist (in Hebrew). Retrieved February 12, 2013.

- ↑ Ben-David, Amir (April 27, 2012). "Plant Thought to Be Extinct Discovered in South". Ynetnews. Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- ↑ Pundak, Hen; Gutman, Lior (March 5, 2013). "National Committee Approved Railway to Eilat Route". Calcalist (in Hebrew). Retrieved March 6, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Bar-Eli, Avi (November 22, 2010). "The Railway to Eilat – Two and a Half Hours; "The Line Will Serve 3.5 Million Passengers a Year"". TheMarker (in Hebrew). Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- ↑ "Israel's Southern Gateway" (PDF). Israel Port Authority. p. 16. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- ↑ Gutman, Lior (September 23, 2014). "Katz: We Will Take Care of Old Port, but Not Pay Ransom to Workers". Calcalist (in Hebrew). Retrieved September 23, 2014.

- ↑ "Suez Canal Authority Against Railway Line to Eilat" (in Hebrew). Port2Port. January 29, 2012. Retrieved June 3, 2012.

External links

- Request for information (RFI) from the Israel Ministry of Transport (PDF)