High-speed rail in Australia

| High-speed rail in Australia | |

|---|---|

|

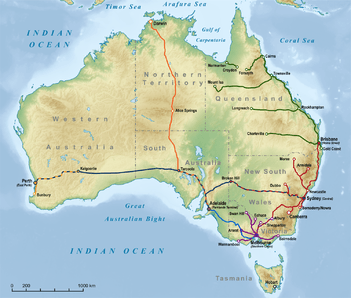

Preferred alignment of Australian east coast high-speed rail system (from the 2013 AECOM study) | |

| Overview | |

| Type | High-speed rail |

| Status | Dormant |

| Locale | Eastern states of Australia |

| Termini |

Brisbane Melbourne |

| Stations | Sydney & Canberra |

| Technical | |

| Operating speed | up to 350 km/h (220 mph) |

High-speed rail in Australia has been under investigation since the early 1980s.[1][2] Every Federal Government since this time has investigated the feasibility of constructing high speed rail, but to date nothing has ever gone beyond the detailed planning stage. The most commonly suggested route is between Australia's two largest cities, Sydney and Melbourne which is the world's fifth busiest air corridor.[3]

The Australian rail speed record of 210 km/h was set by Queensland Rail's Tilt Train during a trial run in 1998.[4] This speed is just above the internationally accepted definition of high-speed rail of 200 km/h (120 mph).[5]

Overview

The construction of a high-speed rail link along the east coast has been the target of several investigations since the early 1980s. Air travel dominates the inter-capital travel market, and intra-rural travel is almost exclusively car-based. Rail has a significant presence in the rural / city fringe commuter market, but inter-capital rail currently has very low market share due to low speeds and infrequent service.[6] However, travel times between the capitals by high-speed rail could be as fast as or faster than air travel[7] – the 2013 High Speed Rail Study Phase 2 Report estimated that conventional High Speed Rail express journeys from Sydney to Melbourne would take 2 hours and 44 minutes, while those from Sydney to Brisbane would take 2 hours and 37 minutes.[8]

Various studies and recommendations have asserted that a high-speed rail service between the major eastern capital cities could be viable as an alternative to air.[9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24] Although such studies have generated much interest from the private sector and captured the imagination of the general public upon their release, to date no private-sector proposal has been able to demonstrate financial viability without the need for significant government assistance.[25]

A mature high-speed rail system would be economically competitive with air and automobile travel, provide mass transit without dependence on imported oil, have a duration of travel that would compare with air travel or be quicker, and would reduce national carbon dioxide emissions.[24][26][27]

Over 12 million people live in the Sydney–Melbourne corridor.[28]

History

1970s–1980s

The rail network has long been a target of proposals for improvement. The 1979 Premiers' Meeting proposed the electrification of the Sydney–Melbourne line to improve transit time from over 12 hours to under 10, but a senate committee found this was not justified on economic grounds. In 1981, the Institution of Engineers proposed the Bicentennial High-Speed Railway Project, which proposed to link the five capitals of south-eastern Australia (Adelaide, Melbourne, Canberra, Sydney and Brisbane) in time for the Australian Bicentenary. However, it proposed only the strengthening and partial electrification of the existing tracks, new deviations to bypass the worst sections, additional passing loops, and the purchase of new diesel-electric trains. It would offer only mild improvements on the existing travel times: Sydney to Canberra in 3 hours, and Sydney to Melbourne in 9; it cannot therefore be considered a true high-speed rail proposal.[1]

1984 CSIRO proposal

The first true high-speed rail proposal was presented to the Hawke Government in June 1984 by the CSIRO, spearheaded by its chairman, Dr Paul Wild.[29] The proposal was to link Melbourne, Canberra and Sydney via a coastal corridor, based on French TGV (Train à Grande Vitesse) technology. The proposal estimated construction costs at A$2.5 billion ($7.0 billion in 2013), with initial revenue of A$150 million per annum exceeding operating costs of A$50 million per annum. The proposal attracted much public and media attention, as well as some private sector capital for feasibility studies.[1][23]

In September 1984, the Bureau of Transport Economics found that the probable construction costs had been underestimated by A$1.5 billion, and the proposal would therefore be uneconomic. The Minister for Transport, Peter Morris, rejected the proposal.[1]

Very Fast Train (VFT) joint venture

Later in 1984 Peter Abeles, chairman of TNT, expressed interest in Dr Wild's proposal.

Two years later in September 1986, the Very Fast Train Joint Venture was established, comprising Elders IXL, Kumagai Gumi, TNT and later BHP, with Dr Wild as chairman. They proposed a 350 km/h rail link from Sydney to Canberra via Goulburn, and then on to Melbourne via the coastal route (or alternatively the inland route). A feasibility study estimated to cost A$19 million ($39.5 million in 2013) was initiated by the group in 1988. In 1989, after talks with the Queensland Government, the joint venture group also performed a preliminary analysis of a coastal link to Brisbane. In 1990 the Joint Venture released the results of the major feasibility study, simply titled VFT - Project Evaluation. It proposed an inland route between Melbourne, Sydney and Canberra, with intermediate stations at Campbelltown, Bowral, Goulburn, Yass, Wagga Wagga, Albury-Wodonga, Benalla, Seymour and Melbourne Airport. It was estimated to cost $6.6 billion ($11.9 billion in 2013) and take five years to construct, beginning in 1992.

The VFT was opposed by numerous groups, notably the Australian Conservation Foundation and the Australian Democrats.[1] Concerns centred around the environmental impact a coastal corridor would have on fragile ecosystems, noise pollution and the amount of public money that might be required.

After the release of the project evaluation, negotiations continued between the Joint Venture and state and federal governments. A favourable tax regime was sought, without which it was claimed that the project would not be economically viable. Premier of South Australia John Bannon was among the vocal proponents of tax breaks for major infrastructure projects such as the VFT.[1] In August 1991, the Hawke Cabinet rejected the proposed tax breaks after it was claimed they would have cost A$1.4 billion. Subsequently the VFT Joint Venture folded.[1][30][31]

Tilting trains

During the 1990s there were several investigations into the use of tilting trains on existing tracks. In January 1990 it was reported that the NSW government was considering upgrading the existing state railway lines to utilise tilting train technology under development by UK engineering giant ASEA Brown Boveri. This was at the same time as the VFT was under investigation, and there was concern that two fast railways could end up being built, which would then both be financially unviable. The tilt train concept could potentially reach speeds of up to 200 kilometres per hour (120 mph) while using the existing tracks.[32]

After the breakup of the VFT joint venture, the NSW government continued to investigate tilt trains for a time. In 1995, CountryLink brought a Swedish Railways X 2000 trainset to New South Wales to conduct an eight-week trial on the Sydney-Canberra route. The test highlighted the deficiencies of the existing track, with tight curvature and inadequate transitions. Speed improvements over the XPT were modest, and the project was abandoned - it was a case of "fast train on slow track".[33]

Speedrail proposal

In 1993, the Speedrail Consortium (a joint venture between Alstom and Leighton Contractors) made a proposal for a high-speed rail link between Sydney and Canberra. It was initially costed at A$2.4 billion ($4.1 billion in 2013). After years of delays and more claims that massive government subsidies would be required,[1] in March 1997 the Commonwealth, New South Wales and ACT governments formally invited expressions of interest; by July, six proponents had been shortlisted. In December 1997, the government received four proposals, all accompanied by the required A$100,000 deposit.[23] The proponents were:

- Capital Rail, backed by ASEA Brown Boveri, Adtranz, SwedeRail, BT Corporate Finance, Ove Arup, TMG International, Ansett and Virgin Rail Group. Their proposal was a $1.2 billion upgrade of the existing line, which would allow a 1 hour 45 minute service using a more powerful 250 km/h variant of the Swedish Railways X 2000 tilting electric multiple unit, dubbed XNEC.

- Inter-Capital Express, backed by AIDC Australia, GHD Transmark, Lend Lease, Siemens, TNT and GB Railways. Proposed journey time and cost the same as for Capital Rail, using similar tilt-train rollingstock and alignment upgrades.

- Speedrail Consortium, Backed by GEC Alsthom, Leighton Contractors, SNCF, Commonwealth Bank, Qantas, and Baulderstone Hornibrook. Proposal involved construction of a new alignment from Glenfield to Canberra at a cost of $2–2.6 billion, and the use of the existing Sydney metro rail network to access Central station. TGV technology would be used, giving a travel time of 1 hour, 20 minutes.

- Transrapid, backed by ThyssenKrupp, BHP, Boral, John Holland, Pacific Dunlop, Siemens and Adtranz, made a radical proposal for a 60-minute magnetic-levitation service via Wollongong. Detailed cost estimates were not given, but government sources estimated the cost to be at least $4 billion.

On 4 August 1998, Prime Minister John Howard announced that Speedrail was the preferred party,[34][35] and gave the go ahead for the project to move into the 'proving up' stage, on the understanding that if the project proceeded, it would be at "no net cost to the taxpayer". It was predicted that construction would cost A$3.5 billion ($5.4 billion in 2013), with 15,000 new jobs created during the construction period. It was planned that the line would use the East Hills line to depart Sydney, and then follow the Hume and Federal highways into Canberra. There would be stations at Central, Campbelltown, Southern Highlands, Goulburn and Canberra Airport. Nine eight-car trainsets would be used, departing from each city at 45-minute intervals, and running at a maximum speed of 320 km/h (199 mph) to complete the journey in 81 minutes.[34] The line was to operate under a build–own–operate model, that would allow a private company to manage the network, but would then be transferred to government after 30 years.

In November 1999, Speedrail submitted a feasibility study to the government, claiming that the project satisfied all the government's requirements.[36] However, the media still speculated that A$1 billion in government assistance or tax concessions would be required.[23] In December 2000, the federal government terminated the proposal due to fears it would require excessive subsidies.

Howard government (2000)

In December 2000 in the wake of the termination of the Speedrail proposal, the Howard Government commissioned TMG International Pty Ltd, leading a team of specialist subconsultants, including Arup, to investigate all aspects of the design and implementation of a high-speed rail system linking Melbourne, Canberra, Sydney and Brisbane. The East Coast Very High Speed Train Scoping Study - Phase 1 was released in November 2001 and cost A$2.3 million to prepare.[37] It dealt with high-speed rail technologies, corridor selection, operating performance and transit times, project costs, projected demand, financing, and national development impacts. Although the preliminary study did not undertake a detailed corridor analysis, it recommended the selection of an inland route between Melbourne and Sydney, and a coastal route between Sydney and Brisbane.

The report concluded that although a high-speed rail system could have a place in Australia's transport future, it would require years of bipartisan political vision to realise (construction time was estimated at 10–20 years), and would most likely require significant financial investment from the government - up to 80% of construction costs.[38][37] Construction cost estimates indicated a strong dependence on the chosen design speed; the construction costs for a double-track east coast high speed railway would be (2001 A$):

- 250 km/h: $33 – $41 billion

- 350 km/h: $38 – $47 billion

- 500 km/h (maglev): $56 – $59 billion

These numbers do not include rollingstock or the cost of setting up the operating company. The report noted that these costs could be reduced somewhat upon detailed corridor analysis (especially the lower speed options) if sections of existing rail or highway corridor could be utilised.

In March 2002, the Government decided not to go ahead with phase 2 of the scoping study due to the finding that an enormous amount of public funding would be required for the massive infrastructure project.[37]

Canberra Business Council study

In April 2008 the Canberra Business Council made a submission to Infrastructure Australia, High Speed Rail for Australia: An opportunity for the 21st century.[24] The submission detailed:

- Improvements in technology, competitiveness and supply over the previous decade.

- Travel demand on the East Coast. The Melbourne – Sydney air route is the fourth busiest in the world and Sydney—Brisbane ranks seventh in the Asia-Pacific region.

- Increased standard of living.

- Use for freight. High-speed freight trains are in use in France and soon to expand across Europe.

- Environmental sustainability and reduced greenhouse gas emissions.

- Energy efficiency.

- Better social outcomes, quality of life, and reduced social disadvantage for regional centres on the rail line.

Canberra Airport plan

In 2009, Canberra Airport proposed that it would be the most appropriate location for a Second Sydney Airport, providing a high-speed rail link was built that could reduce travel times between the cities to 50 minutes. Given the existing development within the Sydney basin, a HSR link will probably be required whatever site is chosen, yet the Canberra option save up to A$22 billion which would be needed to develop a greenfields airport site at Badgerys Creek or Wilton.[39][40] In June 2012, Canberra Airport unveiled plans to build a A$140 million rail terminal at the airport if the high-speed link goes ahead.[40]

Intrastate proposals

At various times, state political parties and others have proposed schemes involving fast trains in other localities that included the potential to achieve speeds above the 200 km/h threshold.

In 2004, the Government of New South Wales proposed a A$2 billion privately funded underground and above-ground train line Western FastRail that would link the Sydney CBD with Western Sydney. The concept was re-proposed in December 2006 by then federal Opposition Leader Kevin Rudd during a visit to Penrith, as part of the Australian Labor Party's election platform. The plan received approving comments by the NSW State Government.[41] The line was also backed by a consortium led by union leader Michael Easson, which includes Dutch bank ABN AMRO and Australian construction company Leighton Contractors.[42] Elements of the proposal were incorporated into the Government's West Metro and CBD Relief Line projects. However, these plans were abandoned following the election of the O'Farrell government in 2011.

In 2008, Transrapid made a proposal to the Government of Victoria to build a privately funded and operated magnetic levitation (maglev) line to serve the Greater Melbourne metropolitan area.[43][44] It was presented as an alternative to the Cross-City Tunnel proposed in the Eddington Transport Report, which neglected to investigate above-ground transport options. The maglev route would connect Geelong to metropolitan Melbourne's outer suburban growth corridors, Tullamarine and Avalon domestic and international terminals in under 20 minutes, continuing to Frankston, Victoria, in under 30 minutes. It would serve a population of over 4 million people, and Transrapid claimed a price of A$4 billion. However, the Victorian government dismissed the proposal in favour of the underground metropolitan network suggested by the Eddington Report.

In 2010, Western Australia's Public Transport Authority completed a feasibility study into a high-speed rail link between Perth and Bunbury. The route would follow the existing narrow gauge Mandurah line to Anketell, then the Kwinana Freeway and Forrest Highway to Lake Clifton, including 140 km (87 mi) of new track.[45] It would replace the existing Transwa Australind passenger service, the route of which is under increasing use for freight traffic. The proposed service would have a maximum speed of 160 km/h (99 mph), at which the travel time from Perth Underground to a new station in central Bunbury would be 91 minutes. The corridor would allow for future upgrade to 200 km/h (120 mph).

In the lead-up to the 2010 Victorian state election, Liberal leader Ted Baillieu promised to spend A$4 million to set up a high-speed rail advocacy unit, with the goal of ensuring Melbourne hosted Australia's first high-speed trains. He expressed support for an east coast link, and extensions west of Melbourne to Geelong and Adelaide.[46][47]

The 2010 Infrastructure Partnerships Australia report identified Noosa-Brisbane-Gold Coast as a potentially viable high-speed rail link, and a possible precursor to a full east-coast system.[48] The report predicted that a 350 km/h (220 mph) system would reduce travel times between Cooroy (22 km west of Noosa) and Brisbane to 31 minutes (currently 2:08 hours), capturing as much as 84% of the total commuter market. Travel time between Brisbane and the Gold Coast would be reduced to 21 minutes, capturing up to 27% of commuters.

Soon after winning the 2011 NSW state election, the incoming Liberal premier Barry O'Farrell advocated high-speed rail lines to Melbourne and Brisbane instead of a second Sydney airport, saying of a new airport site in NSW: "Whether the central coast, the south-west or the western suburbs [of Sydney], find me an area that is not going to end up causing enormous grief to people who currently live around it".[49]

High Speed Rail Study (2011-2013)

Rudd/Gillard government (2008-2013)

In December 2008, the Rudd Government announced that a Very Fast Train along the Sydney–Melbourne corridor, estimated to cost A$25 billion, was the government's highest infrastructure priority.[50][51] On 31 October 2010, the Government issued the terms of reference for a strategic study to inform it and the New South Wales, Victorian, Queensland and Australian Capital Territory governments about implementation of HSR on the east coast of Australia between Melbourne and Brisbane.

The initiative was supported by both the Liberal opposition and the Australian Greens, the latter of which called for the study's scope to be extended to encompass Adelaide and Perth.[52][53]

The $20 million study was undertaken in two phases. The report of phase 1,[54] released on 4 August 2011, identified corridors and station locations and potential patronage, and gave indicative estimates of the cost.[55] The first phase of the study was completed in 2011, projecting a financial cost for high-speed rail of between $61 and A$108 billion, depending on the route and station combination that was selected.[54][56][57]

The phase 1 report found that an HSR corridor between Brisbane and Melbourne could:

- cost between A$61 billion and A$108 billion (2011 dollars)

- involve more than 1,600 kilometres of new standard-gauge, double-track

- achieve speeds of up to 350 kilometres per hour and offer journey times as low as 3 hours between both Brisbane and Sydney and Sydney and Melbourne, 40 minutes from Sydney to Newcastle, and 1 hour between Sydney and Canberra

- carry about 54 million passengers a year by 2036

- offer competitive ticket prices.[54]

The report noted that acquiring, or otherwise preserving the corridor in the short term could reduce future costs by reducing the likelihood of additional tunnels as urban areas grow and preferred corridors become unavailable.[54]

Work on phase 2 of the study started in late 2011 and culminated in the release of the High speed rail study phase 2 report[8] on 11 April 2013.[58] Building on the work of phase 1, it was more comprehensive in objectives and scope, and refined many of the phase 1 estimates, particularly demand and cost estimates.[58]

In 2013 the Australian government released a study on the implementation of high-speed rail on the east coast of Australia, linking Melbourne, Canberra, Sydney, and Brisbane.[58] Some have advocated extending the network to Adelaide[59][46] or as far as Perth on the west coast.[60][52]

The phase 2 report found that:[8]

- the corridor would comprise about 1,750 kilometres of dedicated route linking Brisbane, Sydney, Canberra and Melbourne

- the preferred alignment included four capital city stations, four city-peripheral stations, and stations at the Gold Coast, Casino, Grafton, Coffs Harbour, Port Macquarie, Taree, Newcastle, Southern Highlands, Wagga Wagga, Albury-Wodonga and Shepparton

- once fully operational (from 2065) [sic], the corridor could carry about 84 million passengers a year

- express journey times would be less than three hours between Melbourne and Sydney and between Sydney and Brisbane

- optimal staging for the HSR program would involve building the Sydney–Melbourne line first, starting with Sydney–Canberra, followed by Canberra–Melbourne, Newcastle–Sydney, Brisbane–Gold Coast and Gold Coast–Newcastle

- the estimated cost of constructing the corridor in its entirety would be about A$114 billion (2012 dollars)

- the HSR program and the majority of its individual stages would be expected to produce only a small positive financial return on investment. so governments would need to fund the majority of the upfront capital costs

- if passenger projections were met at the fare levels proposed, the HSR system could generate sufficient revenue from fares and other activities to meet operating costs without ongoing public subsidy

- HSR would substantially improve accessibility for the regional centres it served and provide opportunity for – although not the automatic realisation of – regional development.

Also released alongside the phase 2 report were 280 detailed maps showing the preferred alignment identified in the study. They resolve the various earlier alternative routes outlined in the Wikipedia article Corridor selection history for Australian High Speed Rail.

| Melbourne–Sydney | Sydney–Brisbane | Sydney–Canberra | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rhumb-line distance[61] | 730 km | 770 km | Unknown |

| Existing rail distance[61] | 963 km (32% greater) | 988 km (28% greater) | Unknown |

| Existing rail average speed[61] | 92 km/h | 73 km/h | Unknown |

| Existing rail travel time (h:min)[61] | 10:30 | 13:35 | 4:19[62] |

| Existing rail services (daily, each way)[61] | 2 | 1 | 3[63] |

| Air travel time (CBD to CBD*) (h:min)[61] | 3:00 | 3:05 | 0:55 |

| Air services (daily, each way)[64] | 118 | 84 | Unknown |

| High-speed rail travel time (max. 350 km/h (220 mph))[65] | 2:45 | 4:24 | 1:04[66] |

NOTE: Air travel time includes travel from CBD to airport, waiting at terminal, gate-to-gate transit, and travel to destination CBD.

The major issues preventing the adoption of high-speed rail include, according to Philip Laird:[23]

- a high level of competition in domestic air travel, resulting in highly affordable fares.

- excessive domestic air transport subsidies.

- that the great inter-city distances exceed those for which high-speed rail can compete effectively against aircraft.

- a perception of cheap car travel.

- a lack of tolls on the majority of inter-capital roads.

Abbott/Turnbull government (2013-present)

On 8 November 2013 the High Speed Rail Advisory Group, charged with part of the planning for a very fast train between Brisbane and Melbourne, was one of 20 government committees and councils identified to be wound up as part of the newly elected Abbott Government's initial efforts to cut costs and "ensure that the machinery of government is as efficient and as small as possible".[67][68]

However, the following month, former Deputy Prime Minister Warren Truss[69][70][71] announced that the Coalition was committed to acquiring the land corridor identified by the previous government's study, and that he was personally seeking the co-operation of the premiers of Victoria, New South Wales and Queensland, and the Chief Minister of the ACT.

The Labor Party indicated it would support the move.[72]

Beyond Zero Emissions Study (2014)

In 2014, the low-carbon advocacy group Beyond Zero Emissions released a detailed study in response to the Rudd government's Phase 2 report. Prepared in collaboration with the German Aerospace Centre, the study used many of the same cost assumptions but proposed a modified route to minimise construction expense. Although slightly longer (1799 km compared to 1748 km), the length in tunnel was reduced by 44%, and the length on bridges by 25%. Much of the reduction came through making greater use of existing transport corridors for metropolitan access; the government study took the politically uncomplicated but extremely expensive option of simply tunnelling to the terminal stations. Project author Gerard Drew also criticised the Phase 2 Report's 45-year construction timeline, calling it "laughable". Drew also suggested that there was significant "gold plating" evident in the government report's cost estimates. BZE forecast that the high-speed railway would cost $84.3 billion and take 10 years to construct.[73][74]

CLARA Proposal (2016-present)

A newly formed joint venture named CLARA ("Consolidated Land and Rail Australia") met with government and opposition officials to discuss a solution using Japan Railways' SC Maglev, with a trip of 1 hour 50 minutes from Sydney to Melbourne. In March they scheduled a meeting to make an unsolicited offer to the prime minister Malcolm Turnbull, a noted train enthusiast, to link Melbourne to Sydney with a fast train line.[75]

CLARA partners Japan Railways Central, Mitsui and General Electric to provide a commercial funding model using private investors, that could build a SC Maglev linking Sydney, Canberra and Melbourne, while creating 8 new self-sustaining inland cities linked to the high speed connection and contributing to the community.[76][77]

In April, Turnbull suggested that a staged construction could begin with links from capital cities to regional areas, and that construction could be financed by value capture. [78] However, the government did not propose to allocate any taxpayer funds toward the project.

See also

- AVE

- NTV Italo

- TGV

- Intercity-Express

- Eurostar

- Shinkansen

- Peak oil

- High-speed rail

- Rail transport in Australia

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Williams 1998.

- ↑ Crikey - BZE: How we found high speed rail to be commercially viable

- ↑ Melbourne-Sydney is worlf's fifth busiest airline route Australian Business Traveller 10 May 2013

- ↑ Stephen Lacey (3 March 2013). "Speed freak". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ↑ General definitions of highspeed, International Union of Railways, archived from the original on 20 July 2011, retrieved 10 October 2012

- ↑ "Australian transport statistics" (PDF). Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics. June 2008. Retrieved 2 March 2009.

- ↑ "Peak Oil and Australia's National Infrastructure" (PDF). Australian Association for the Study of Peak Oil and Gas. October 2008. Retrieved 2 March 2009.

- 1 2 3 High Speed Rail Study Phase 2 Report 2013.

- ↑ Laird, P.; Michell, M.; Adorni-Braccesi, G (2002). Sydney–Canberra–Melbourne high-speed train options (PDF). 25th Australasian Transport Research Forum 2–4 October. Canberra.

- ↑ May, Murray (2006). "Aviation meets ecology—redesigning policy and practice for air transport and tourism". Transport Engineering in Australia. 10 (2): 117–128.

- ↑ Brunello, Lara R; Bunker, Jonathan M.; Ferreira, Luis (2006). Investigation to Enhance Sustainable Improvements in High Speed Rail Transportation (PDF). CAITR, 6,7,8 December 2006. Sydney.

- ↑ May, Murray; Hill, Stuart B. (November 2006). "Questioning airport expansion—A case study of Canberra International Airport". Journal of Transport Geography. 14 (6): 437–450. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2005.10.004.

- ↑ Brunello, Lara R; Bunker, Jonathan M.; Ferreira, Luis; Ferrara, Renzo (2008). Enhancing Sustainable Road and Rail Interaction. Transport Research Arena Europe 2008: Greener, Safer and Smarter Road Transport for Europe, 21–24 April 2008. Ljubljana, Slovenia.

- ↑ "A Fast Railway for the East Coast". Railway Digest. 44 (8). August 2007.

- ↑ "Fast Future or a Slow Death". Railway Digest. 44 (9). September 2007.

- ↑ "Fast Freight and Passengers". Railway Digest. 44 (10). October 2007.

- ↑ "Mixing Fast Freight and Passenger Trains". Railway Digest. 44 (11). November 2007.

- ↑ "Costing a 21st Century Railway". Railway Digest. 44 (12). December 2007.

- ↑ "Fast Trains – Profit or Loss". Railway Digest. 45 (1). January 2008.

- ↑ "Fast Trains – Financially Viable". Railway Digest. 45 (2). February 2008.

- ↑ "Fast Trains – External Benefits". Railway Digest. 45 (3). March 2008.

- ↑ Colin Butcher. "(Submission)Towards a National Land Transport Plan : A Response to the Green Paper on AUSLINK" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Laird 2001.

- 1 2 3 High Speed Rail for Australia: An opportunity for the 21st century 2008.

- ↑ East Coast Very High Speed Train Scoping Study: Phase 1 – Preliminary Study Final Report 2001, section 1, page 1.

- ↑ Steketee, Mike (26 July 2008). "Greenhouse plans went off the rails". The Australian. News Corp Australia. Retrieved 2 March 2009.

- ↑ Thistleton, John (26 November 2008). "Very fast train tops develops' wish-list". The Canberra Times. Fairfax Media. Retrieved 1 March 2009.

- ↑ "Immigrants 'to fund fast rail'". The Border Mail. Fairfax Media. 17 April 2012. Archived from the original on 28 August 2013.

- ↑ "WILD John Paul". Obituary. ATSE, reprinting article from Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 20 July 2008.

- ↑ East Coast Very High Speed Train Scoping Study: Phase 1 – Preliminary Study Final Report 2001.

- ↑ Boyd, Tony (5 February 2009). "On the wrong track". Business Spectator. Archived from the original on 6 September 2012.

- ↑ "New fast train proposal tilts at VFT.". The Canberra Times. ACT: National Library of Australia. 19 January 1990. p. 5. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- ↑ Philip G. Laird; Peter Newman; Mark Bachels; Jeffry Kenworthy (2001). Back on Track : Rethinking Transport Policy in Australia and New Zealand. UNSW Press.

- 1 2 Philip Laird (2001). The Institutional Problem. Back on Track. UNSW Press. pp. 107–108. ISBN 0-86840-411-X.

- ↑ John Howard; Mark Vaile (4 August 1998). "News release: "It's Speedrail!"". Commonwealth of Australia. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ↑ Mark, David (11 December 2000). "A history of the Very Fast Train". PM. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 8 August 2010.

- 1 2 3 Anderson 2001.

- ↑ East Coast Very High Speed Train Scoping Study: Phase 1 – Preliminary Study Final Report 2001, preamble, page 5.

- ↑ Jano Gibson (10 February 2009). "Sydney to Canberra in 50 minutes: fast tracking second airport". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 5 August 2010.

- 1 2 John Thistleton (18 June 2012). "$22b savings seen in high-speed rail link". Canberra Times. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ↑ Hildebrand, J. Rudd's road and rail cash. Daily Telegraph 19 December 2006

- ↑ Smith, A. Parramatta to city in 11 minutes: now that's a fast train. Sydney Morning Herald 15 March 2005

- ↑ Hast, Mike (3 August 2008). "Rapid train could slash travel times". The Cranbourne Journal. Retrieved 8 August 2010.

- ↑ "Melbourne Concepts – E Page 3: Maglev's relevence(sic) to Western Melbourne". Archived from the original on 12 May 2013.

- ↑ Paul Fisher. "Perth Bunbury Fast Train Feasibility study and route selection". Archived from the original on 13 October 2012.

- 1 2 Clay Lucas (23 November 2010), Baillieu pushes high-speed rail links, Melbourne: The Age, archived from the original on 6 November 2012

- ↑ Baillieu, Ted (23 November 2010). "Coalition to push for high-speed rail" (PDF) (Press release). Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ↑ Tony Moore (19 November 2010), High-speed rail plan: Brisbane to Gold Coast in 21 minutes, Brisbane Times, archived from the original on 8 October 2012

- ↑ Jacob Saulwick and Kelsey Munro (6 April 2011). "O'Farrell calls for high-speed trains instead of second Sydney airport". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012.

- ↑ Peter Veness (20 December 2008). "Melbourne-Sydney very fast train tops wish list for Rudd Government". news.com.au. Archived from the original on 4 February 2009. Retrieved 26 February 2009.

- ↑ "Very fast train has merits: Albanese". ABC. 19 March 2008. Archived from the original on 16 March 2011. Retrieved 26 February 2009.

- 1 2 Needham, Kirsty (1 November 2010). "Study will examine cost of fast rail". The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2010.

- ↑ Lucas, Clay (23 April 2010). "Greens to push A$40bn fast-rail link to Sydney". The Age. Melbourne. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 High Speed Rail Study Phase 1 2011.

- ↑ Albanese, Anthony. "Moving forward with high speed rail". Anthony Albanese MP. Archived from the original on 9 March 2013. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- ↑ High speed rail study underway, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 2 February 2011, archived from the original on 12 November 2012

- ↑ Saulwick, Jacol (28 September 2010). "High speed rail between Sydney and Melbourne too expensive". Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- 1 2 3 "High Speed Rail". Department of Infrastructure and Transport. Archived from the original on 14 August 2013.

- ↑ Russell, Christopher (31 January 2011), Adelaide must be in high-speed rail loop, archived from the original on 1 July 2012

- ↑ Wright, Matthew (27 August 2009). "Fly by rail – Zero Emissions transport capital to capital". Beyond Zero Emissions campaign. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 East Coast Very High Speed Train Scoping Study: Phase 1 – Preliminary Study Final Report 2001, section 1, page 5.

- ↑ Saulwick, Jacob (15 August 2012). "Tilt trains seen as way to lure users to rural rail". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- ↑ "Countrylink". Archived from the original on 6 May 2013.

- ↑ "OAG reveals latest industry intelligence on the busiest routes (Press release)". OAG (UBM Aviation). 21 September 2007. Retrieved 8 August 2010.

- ↑ Jacob Saulwick (26 August 2013). "High-Speed Rail back on track". Canberra Times.

- ↑ John Thistleton (26 August 2013). "Canberra-Sydney high-speed rail link backed in advisory group's report". The Examiner.

- ↑ Marr, Sid and Crowe, David (8 November 2013). "Tony Abbott keeps focus by cutting bodies past use-by date". The Australian. Sydney. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ↑ Abbott, Tony (8 November 2013). "Media release: "Press conference, Melbourne"". Commonwealth of Australia. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ↑ Murphy, Katharine (11 February 2016). "Barnaby Joyce wins Nationals leadership, Fiona Nash named deputy". The Guardian. Australia. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ↑ Gartrell, Adam (11 February 2016). "Parliament pays tribute to retiring deputy PM Warren Truss ahead of Barnaby Joyce elevation". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ↑ Keany, Francis (11 February 2016). "Barnaby Joyce elected unopposed as new Nationals leader". ABC News. Australia. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ↑ Ross Peake (2 December 2013). "Deputy Prime Minister Warren Truss gets high speed rail on track". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 22 June 2014.

- ↑ Gerard Drew, Earth to moon in 8 years, Melbourne to Brisbane in 45, Beyond Zero Emissions, retrieved 1 March 2015

- ↑ Jake Sturmer (29 November 2013), High-speed rail network $30 billion cheaper than first thought: study, ABC, retrieved 1 March 2015

- ↑ "Is this secret meeting with the PM about a speed rail link for Australia?". NewsComAu. Retrieved 2016-06-22.

- ↑ "General Electric, Japan Rail and Mitsui all aboard high-speed rail proposal". Financial Review. 2016-05-12. Retrieved 2016-06-22.

- ↑ "Consolidated Land and Rail Australia Pty Ltd". www.clara.com.au. Retrieved 2016-06-22.

- ↑ High speed rail proposal raised by Malcolm Turnbull 7.30 11 April 2016

Sources

- AECOM; Booz and Co; KPMG; Hyder; Acil Tasman; Grimshaw Architects (April 2013). "High Speed Rail Study Phase 2 Report" (PDF). Australian Government Department of Infrastructure and Transport. Libraries Australia ID 50778307. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 June 2013.

- AECOM; Grimshaw Architects; KPMG; SKM (July 2011). "High Speed Rail Study Phase 1" (PDF). Australian Government Department of Infrastructure and Transport. Libraries Australia ID 47757259. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 May 2013.

- Anderson, John (26 March 2001), Government ends scoping study on East Coast very high speed train network (Media Release) (PDF), Parliament of Australia, retrieved 8 August 2010

- Arup-TMG (November 2001). "East Coast Very High Speed Train Scoping Study: Phase 1 – Preliminary Study Final Report" (PDF). Australian Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2013.

- Brown, Lester R. (17 February 2009). "Restructuring the U.S. Transport System: The Potential of High-Speed Rail". The Permaculture Research Institute of Australia. Archived from the original on 27 March 2012.

- Canberra Business Council (April 2008). "High Speed Rail for Australia: An opportunity for the 21st century" (PDF). Canberra Business Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2013.

- CSIRO (January 1985). VFT – A Fast Railway Between Sydney, Canberra and Melbourne: a CSIRO Proposal. Canberra: CSIRO.

- de Rus, Ginés; Nombela, Gustavo (March 2006), Is Investment in High Speed Rail Socially Profitable? (PDF), Department of Applied Economic Analysis, University of Las Palmas, archived from the original (PDF) on 20 February 2012

- Infrastructure Partnerships Australia; AECOM (2010). "East Coast High Capacity Infrastructure Corridors". Infrastructure Partners Australia. Archived from the original on 10 July 2011.

- Laird, Philip (2001). Where Are We Now: National Patterns and Trends in Transport. Back on Track. UNSW Press. pp. 32–33. ISBN 0-86840-411-X.

- McLennan, David (29 March 2002). "Fast train shelved by lack of vision: Stanhope". The Canberra Times. Archived from the original on 21 October 2009.

- Sarre, Alastair (January 2002). "Looking down the track at very fast trains". Australian Academy of Science. Archived from the original on 29 June 2012.

- Teutsch, Danielle (6 April 2008). "Planes versus trains". Melbourne: The Age. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012.

- Wild, J.P.; Brotchie, J.F.; Nicolson, A.J. (1984), A proposal for a fast railway between Sydney, Canberra and Melbourne : an exploratory study, CSIRO Australia

- Williams, Paula (April 1998), "Australian Very Fast Trains – A Chronology", Background Paper 16, Parliamentary Library, archived from the original on 7 February 2012

_of_Australian_east_coast_high_speed_rail_system.jpg)