Henry George

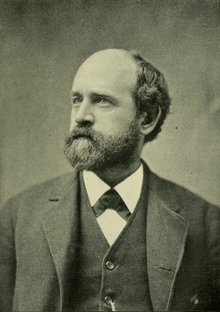

| Henry George | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

September 2, 1839 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA |

| Died |

October 29, 1897 (aged 58) New York City |

| Resting place | Green-Wood Cemetery, Brooklyn, New York |

| Nationality | American |

| Spouse(s) | Annie Corsina Fox |

| School or tradition | Classical economics |

| Influences | |

| Influenced |

|

| Contributions | Georgism; studied land as a factor in economic inequality and business cycles; proposed land value tax |

Henry George (September 2, 1839 – October 29, 1897) was an American political economist, journalist, and philosopher. His immensely popular writing is credited with sparking several reform movements of the Progressive Era, and inspiring the broad economic philosophy known as Georgism, based on the belief that people should own the value they produce themselves, but that the economic value derived from land (including natural resources) should belong equally to all members of society.

His most famous work, Progress and Poverty (1879), sold millions of copies worldwide, probably more than any other American book before that time. The treatise investigates the paradox of increasing inequality and poverty amid economic and technological progress, the cyclic nature of industrialized economies, and the land value tax as a remedy for these social problems.

Biography

Life and career

George was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to a lower-middle-class family, the second of ten children of Richard S. H. George and Catharine Pratt George (née Vallance). His father was a publisher of religious texts and a devout Episcopalian, and sent George to the Episcopal Academy in Philadelphia. George chafed at his religious upbringing and left the academy without graduating.[8][9] Instead he convinced his father to hire a tutor and supplemented this with avid reading and attending lectures at the Franklin institute.[10] His formal education ended at age 14 and he went to sea as a foremast boy at age 15 in April 1855 on the Hindoo, bound for Melbourne and Calcutta. He ended up in the West in 1858 and briefly considered prospecting for gold but instead started work the same year in San Francisco as a type setter.[10]

In California, George fell in love with Annie Corsina Fox, an eighteen-year-old girl from Sydney who had been orphaned and was living with an uncle. The uncle, a prosperous, strong-minded man, was opposed to his niece's impoverished suitor. But the couple, defying him, eloped and married in late 1861, with Henry dressed in a borrowed suit and Annie bringing only a packet of books. The marriage was a happy one and four children were born to them. Fox's mother was Irish Catholic, and while George remained an Evangelical Protestant, the children were raised Catholic. On November 3, 1862 Annie gave birth to future United States Representative from New York, Henry George, Jr. (1862–1916). Early on, even with the birth of future sculptor, Richard F. George (1865 – September 28, 1912),[11][12][13] the family was near starvation.

After deciding against gold mining in British Columbia, George was hired as a printer for the newly created San Francisco Times,[14] and was able to immediately submit editorials for publication, including the popular What the Railroads Will Bring Us., which remained required reading in California schools for decades. George climbed the ranks of the Times, eventually becoming managing editor in the summer of 1867.[15][16] George worked for several papers, including four years (1871–1875) as editor of his own newspaper San Francisco Daily Evening Post and time running the Reporter, a Democratic anti-monopoly publication.[17][18][19] The George family struggled but George's increasing reputation and involvement in the newspaper industry lifted them from poverty.

George's other two children were both daughters. The first was Jennie George, (c. 1867–1897), later to become Jennie George Atkinson.[20] George's other daughter was Anna Angela George (b. 1879), who would become mother of both future dancer and choreographer, Agnes de Mille[21] and future actress Peggy George (who was born Margaret George de Mille).[22][23]

Economic and political philosophy

George began as a Lincoln Republican, but then became a Democrat. He was a strong critic of railroad and mining interests, corrupt politicians, land speculators, and labor contractors. He first articulated his views in an 1868 article entitled "What the Railroad Will Bring Us." George argued that the boom in railroad construction would benefit only the lucky few who owned interests in the railroads and other related enterprises, while throwing the greater part of the population into abject poverty. This had led to him earning the enmity of the Central Pacific Railroad's executives, who helped defeat his bid for election to the California State Assembly.[19][24][25]

One day in 1871 George went for a horseback ride and stopped to rest while overlooking San Francisco Bay. He later wrote of the revelation that he had:

I asked a passing teamster, for want of something better to say, what land was worth there. He pointed to some cows grazing so far off that they looked like mice, and said, 'I don't know exactly, but there is a man over there who will sell some land for a thousand dollars an acre.' Like a flash it came over me that there was the reason of advancing poverty with advancing wealth. With the growth of population, land grows in value, and the men who work it must pay more for the privilege.[26]

Furthermore, on a visit to New York City, he was struck by the apparent paradox that the poor in that long-established city were much worse off than the poor in less developed California. These observations supplied the theme and title for his 1879 book Progress and Poverty, which was a great success, selling over 3 million copies. In it George made the argument that a sizeable portion of the wealth created by social and technological advances in a free market economy is possessed by land owners and monopolists via economic rents, and that this concentration of unearned wealth is the main cause of poverty. George considered it a great injustice that private profit was being earned from restricting access to natural resources while productive activity was burdened with heavy taxes, and indicated that such a system was equivalent to slavery – a concept somewhat similar to wage slavery. This is also the work in which he made the case for a land value tax in which governments would tax the value of the land itself, thus preventing private interests from profiting upon its mere possession, but allowing the value of all improvements made to that land to remain with investors.[27][28]

George was in a position to discover this pattern, having experienced poverty himself, knowing many different societies from his travels, and living in California at a time of rapid growth. In particular he had noticed that the construction of railroads in California was increasing land values and rents as fast as or faster than wages were rising.[24][29]

In 1880, now a popular writer and speaker,[30] George moved to New York City, becoming closely allied with the Irish nationalist community despite being of English ancestry. From there he made several speaking journeys abroad to places such as Ireland and Scotland where access to land was (and still is) a major political issue. In 1886 George campaigned for mayor of New York City as the candidate of the United Labor Party, the short-lived political society of the Central Labor Union. He polled second, more than the Republican candidate Theodore Roosevelt. The election was won by Tammany Hall candidate Abram Stevens Hewitt by what many of George's supporters believed was fraud. In the 1887 New York state elections, George came in a distant third in the election for Secretary of State of New York.[19][31] The United Labor Party was soon weakened by internal divisions: the management was essentially Georgist, but as a party of organized labor it also included some Marxist members who did not want to distinguish between land and capital, many Catholic members who were discouraged by the excommunication of Father Edward McGlynn, and many who disagreed with George's free trade policy. George had particular trouble with Terrence V. Powderly, president of the Knights of Labor, a key member of the United Labor coalition. While initially friendly with Powderly, George vigorously opposed the tariff policies which Powderly and many other labor leaders thought vital to the protection of American workers. George's strident criticism of the tariff set him against Powderly and others in the labor movement.[32]

Death and funeral

George's first stroke occurred in 1890, after a global speaking tour concerning land rights and the relationship between rent and poverty. This stroke greatly weakened him, and he never truly recovered. Despite this, George tried to remain active in politics. Against the advice of his doctors, George campaigned for New York City mayor again in 1897, this time as an Independent Democrat. The strain of the campaign precipitated a second stroke, leading to his death four days before the election.[33][34][35]

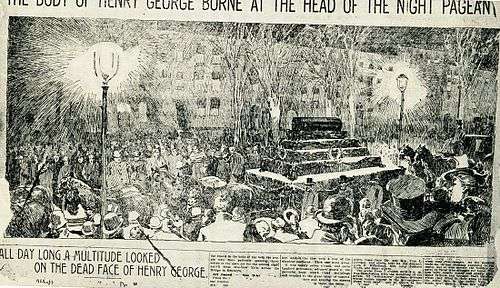

An estimated 100,000 people visited Grand Central Palace during the day to see Henry George's face, with an estimated equal number[36] crowding outside, unable to enter, and held back by police. After the Palace doors closed, the reverend Lyman Abbott, father Edward McGlynn, rabbi Gustav Gottheil, R. Heber Newton (Episcopalian), and John Sherwin Crosby delivered addresses.[37] Separate memorial services were held elsewhere. In Chicago, five thousand people waited in line to hear memorial addresses by the former governor of Illinois, John Peter Altgeld, and John Lancaster Spalding.[38]

The New York Times reported that later in the evening, an organized funeral procession of about 2,000 people left from the Grand Central Palace and made its way through Manhattan to the Brooklyn Bridge. This procession was "all the way . . . thronged on either side by crowds of silent watchers."

The procession then went on to Brooklyn, where the crowd at Brooklyn City Hall "was the densest ever seen there." There were "thousands on thousands" at City Hall who were so far back that they could not see the funeral procession pass. It was impossible to move on any of the nearby streets. The Times wrote, "Rarely has such an enormous crowd turned out in Brooklyn on any occasion," but that nonetheless, "[t]he slow tolling of the City Hall bell and the regular beating of drums were the only sounds that broke the stillness. . . . Anything more impressive . . . could not be imagined."[39] At Court Street, the casket was transferred to a hearse and taken to a private funeral at Fort Hamilton. Commentators disagreed on whether it was the largest funeral in New York history or the largest since the death of Abraham Lincoln. The New York Times reported, "Not even Lincoln had a more glorious death."[40] Even the more conservative New York Sun wrote that "Since the Civil War, few announcements have been more startling than that of the sudden death of Henry George."[41]

-

The grave of Henry George, Green-Wood Cemetery

Policy proposals

Socialization of land and natural resource rents

Henry George is best known for his argument that the economic rent of land (location) should be shared by society. The clearest statement of this view is found in Progress and Poverty: "We must make land common property."[42][43] By taxing land values, society could recapture the value of its common inheritance, raise wages, improve land use, and eliminate the need for taxes on productive activity. George believed it would remove existing incentives toward land speculation and encourage development, as landlords would not suffer tax penalties for any industry or edifice constructed on their land and could not profit by holding valuable sites vacant.[44]

Broadly applying this principle is now commonly known as 'Georgism'. In George's time, it was known as the 'single-tax' movement and sometimes associated with movements for land nationalization, especially in Ireland.[45][46][47] However, in Progress and Poverty, George unequivocally rejected the idea of nationalization.

"I do not propose either to purchase or to confiscate private property in land. The first would be unjust; the second, needless. Let the individuals who now hold it still retain, if they want to, possession of what they are pleased to call their land. Let them continue to call it their land. Let them buy and sell, and bequeath and devise it. We may safely leave them the shell, if we take the kernel. It is not necessary to confiscate land; it is only necessary to confiscate rent."[48]

Municipalization of utilities and free public transit

George considered businesses relying on exclusive right-of-way land privilege to be "natural" monopolies. Examples of these services included the transportation of utilities (water, electricity, sewage), information (telecommunications), goods, and travelers. George advocated that these systems of transport along "public ways" should usually be managed as public utilities and provided for free or at marginal cost. In some cases, it might be possible to allow competition between private service providers along public 'rights of way', such as parcel shipping companies that operate on public roads, but wherever competition would be impossible, George supported complete municipalization. George said that these services would be provided for free because investments in beneficial public goods always tend to increase land values by more than the total cost of those investments. George used the example of urban buildings that provide free vertical transit, paid out of some of the increased value that residents derive from the addition of elevators.[49][50]

Intellectual property reform

George was opposed to or suspicious of all intellectual property privilege, because his classical definition of 'land' included "all natural forces and opportunities". Therefore, George proposed to abolish or greatly limit intellectual property privilege. In George's view, owning a monopoly over specific arrangements and interactions of materials, governed by the forces of nature, allowed title-holders to extract royalty-rents from producers, in a way similar to owners of ordinary land titles. George later supported limited copyright, on the ground that temporary property over a unique arrangement of words or colors did not in any way prevent others from laboring to make other works of art. George apparently ranked patent rents as a less significant form of monopoly than the owners of land title deeds, partly because he viewed the owners of locations as "the robber that takes all that is left". People could choose not to buy a specific new product, but they cannot choose to lack a place upon which to stand, so benefits gained for labor through lesser reforms would tend to eventually be captured by owners and financers of location monopoly.

Free trade

George was opposed to tariffs, which were at the time both the major method of protectionist trade policy and an important source of federal revenue (the federal income tax having not yet been introduced). He believed that tariffs kept prices high for consumers, while failing to produce any increase in wages. He also thought that tariffs protected monopolistic companies from competition, thus augmenting their power. Later in his life, free trade became a major issue in federal politics and his book Protection or Free Trade was read into the Congressional Record by five Democratic congressmen.[51][52]

Spencer MacCallum wrote that Henry George was "Undeniably the greatest writer and orator on free trade who ever lived."[53] Tyler Cowen wrote that George's 1886 book, Protection or Free Trade "remains perhaps the best-argued tract on free trade to this day."[54]

Secret ballot

George was one of the earliest, strongest and most prominent advocates for adoption of the secret ballot in the United States.[55] Harvard historian Jill Lepore asserts that Henry George's advocacy is the reason Americans vote with secret ballots today.[40] George's first article in support of the secret ballot was entitled "Bribery in Elections" and published in the Overland Review of December 1871. His second article was "Money in Elections," published in the North American Review of March 1883. The first secret ballot reform approved by a state legislature was brought about by reformers who said they were influenced by George.[56] The first state to adopt the secret ballot, also called The Australian Ballot, was Massachusetts in 1888 under the leadership of Richard Henry Dana III. By 1891, more than half the states had adopted it too.[57]

Money creation, banking, and national deficit reform

George supported the use of 'debt free' (sovereign money) currency, such as the greenback, which governments would spend into circulation to help finance public spending through the capture of seigniorage rents. He opposed the use of metallic currency (such as gold or silver) and fiat money created by private commercial banks.[58]

Citizen's dividend and universal pension

George proposed to create a pension and disability system, and an unconditional basic income from surplus land rents. It would be distributed to residents "as a right" instead of as charity. Georgists often refer to this policy as a citizen's dividend in reference to a similar proposal by Thomas Paine.

Bankruptcy protection and an abolition of debtors' prisons

George noted that most debt, though bearing the appearance of genuine capital interest, was not issued for the purpose of creating true capital, but instead as an obligation against rental flows from existing economic privilege. George therefore reasoned that the state should not provide aid to creditors in the form of sheriffs, constables, courts, and prisons to enforce collection on these illegitimate obligations. George did not provide any data to support this view, but in today's developed economies, much of the supply of credit is created to purchase claims on future land rents, rather than to finance the creation of true capital. Michael Hudson (economist) and Adair Turner estimate that about 80 percent of credit finances real estate purchases, mostly land.[59][60]

George acknowledged that this policy would limit the banking system but believed that would actually be an economic boon, since the financial sector, in its existing form, was mostly augmenting rent extraction, as opposed to productive investment. "The curse of credit," George wrote, was ". . . that it expands when there is a tendency to speculation, and sharply contracts just when most needed to assure confidence and prevent industrial waste." George even said that a debt jubilee could remove the accumulation of burdensome obligations without reducing aggregate wealth.[61]

Other proposals

Henry George also proposed the following reforms:

- to dramatically reduce the size of the military,

- to replace contract patronage with the direct employment of government workers, with civil-service protections,

- to build and maintain free mass transportation and libraries,[62]

- to extend suffrage to women,[63] and even to have one house of Congress entirely male and the other entirely female,

- to implement campaign finance reform and political spending restrictions.

Legacy

Henry George's ideas on economics, now known as Georgism, had enormous influence in his time. However, his influence slowly waned throughout the 20th century. Nonetheless, it would be difficult to overstate George's impact on turn-of-the-century reform movements and intellectual culture. George's self-published Progress and Poverty was the first popular economics text and one of the most widely printed books ever written. The book's explosive worldwide popularity is often marked as the beginning of the Progressive Era and various political parties, clubs, and charitable organizations around the world were founded on George's ideas. George's message attracts support widely across the political spectrum, including labor union activists, socialists, anarchists, libertarians, reformers, conservatives, and wealthy investors. As a result, Henry George is still claimed as a primary intellectual influence by both classical liberals and socialists. Edwin Markham expressed a common sentiment when he said, "Henry George has always been to me one of the supreme heroes of humanity."[64]

A large number of famous individuals, particularly Progressive Era figures, claim inspiration from Henry George's ideas. John Peter Altgeld wrote that George "made almost as great an impression on the economic thought of the age as Darwin did on the world of science."[65] Jose Marti wrote, "Only Darwin in the natural sciences has made a mark comparable to George's on social science.[66] In 1892, Alfred Russel Wallace stated that George's Progress and Poverty was "undoubtedly the most remarkable and important book of the present century," implicitly placing it above even The Origin of Species, which he had earlier help develop and publicize.[67]

Franklin D. Roosevelt praised George as "one of the really great thinkers produced by our country" and bemoaned the fact that George's writings were not better known and understood.[68] Yet even several decades earlier, William Jennings Bryan wrote that George's genius had reached the global reading public and that he "was one of the foremost thinkers of the world."[69]

John Dewey wrote, "It would require less than the fingers of the two hands to enumerate those who from Plato down rank with him," and that "No man, no graduate of a higher educational institution, has a right to regard himself as an educated man in social thought unless he has some first-hand acquaintance with the theoretical contribution of this great American thinker."[70] Albert Jay Nock wrote that anyone who rediscovers Henry George will find that "George was one of the first half-dozen [greatest] minds of the nineteenth century, in all the world.”[71] The anti-war activist John Haynes Holmes echoed that sentiment by commenting that George was "one of the half-dozen great Americans of the nineteenth century, and one of the outstanding social reformers of all time."[72] Edward McGlynn said, "[George] is one of the greatest geniuses that the world has ever seen, and . . . the qualities of his heart fully equal the magnificent gifts of his intellect. . . . He is a man who could have towered above all his equals in almost any line of literary or scientific pursuit."[73] Likewise, Leo Tolstoy wrote that George was "one of the greatest men of the 19th century."[74]

The social scientist and economist John A. Hobson observed in 1897 that “Henry George may be considered to have exercised a more directly powerful formative and educative influence over English radicalism of the last fifteen years than any other man,”[75] and that George "was able to drive an abstract notion, that of economic rent, into the minds of a large number of ‘practical’ men, and so generate therefrom a social movement. George had all the popular gifts of the American orator and journalist, with something more. Sincerity rang out of every utterance."[76] Many others agree with Hobson. George Bernard Shaw claims that Henry George was responsible for inspiring 5 out of 6 socialist reformers in Britain during the 1880s, who created socialist organizations such as the Fabian Society.[77] The controversial People's Budget and the Land Values (Scotland) Bill were inspired by Henry George and resulted in a constitutional crisis and the Parliament Act 1911 to reform of the House of Lords, which had blocked the land reform. In Denmark, the Danmarks Retsforbund (known in English as the Justice Party or Single-Tax Party) was founded in 1919. The party's platform is based upon the land tax principles of Henry George. The party was elected to parliament for the first time in 1926, and they were moderately successful in the post-war period and managed to join a governing coalition with the Social Democrats and the Social Liberal Party from the years 1957–60, with diminishing success afterwards.

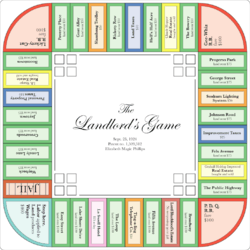

Non-political means have also been attempted to further the cause. A number of "Single Tax Colonies" were started, such as Arden, Delaware and Fairhope, Alabama. In 1904, Lizzie Magie created a board game called The Landlord's Game to demonstrate George's theories. This was later turned into the popular board game Monopoly.

Before reading Progress and Poverty, Helen Keller was a socialist who believed that Georgism was a good step in the right direction.[78] She later wrote of finding "in Henry George’s philosophy a rare beauty and power of inspiration, and a splendid faith in the essential nobility of human nature."[79] Some speculate that the passion, sincerity, clear explanations evident in Henry George's writing account for the almost religious passion that many believers in George's theories exhibit, and that the promised possibility of creating heaven on Earth filled a spiritual void during an era of secularization.[80] Josiah Wedgwood, the Liberal and later Labour Party politician wrote that ever since reading Henry George's work, "I have known 'that there was a man from God, and his name was Henry George.' I had no need hence-forth for any other faith."[81]

Although both advocated worker's rights, Henry George and Karl Marx were antagonists. Marx saw the Single Tax platform as a step backwards from the transition to communism.[82] On his part, Henry George predicted that if Marx's ideas were tried, the likely result would be a dictatorship.[83] Leo Tolstoy deplored that a silence had fallen around George, for he viewed Georgism as reasonable and realistic, as opposed to other utopian movements,[84] and as a "contribution to the enlightenment of the consciousness of mankind, placed on a practical footing,”[85][86] and that it could help do away with what he called the Slavery of Our Times.”[87]

Henry George's popularity waned gradually during the 20th century. However, there are still Georgist organizations. Many influential people who remain famous, such as George Bernard Shaw, were inspired by George or identify as Georgists. In his last book, Where do we go from here: Chaos or Community?, Martin Luther King, Jr referred to Henry George in support of a guaranteed minimum income. Bill Moyers quoted Henry George in a speech and identified George as a "great personal hero".[88] Albert Einstein wrote that "Men like Henry George are rare unfortunately. One cannot imagine a more beautiful combination of intellectual keenness, artistic form and fervent love of justice. Every line is written as if for our generation. The spreading of these works is a really deserving cause, for our generation especially has many and important things to learn from Henry George."[89]

Mason Gaffney, an American economist and a major Georgist critic of neoclassical economics, argued that neoclassical economics was designed and promoted by landowners and their hired economists to divert attention from George's extremely popular philosophy that since land and resources are provided by nature, and their value is given by society, land value – rather than labor or capital – should provide the tax base to fund government and its expenditures.[90]

Joseph Stiglitz wrote that "One of the most important but underappreciated ideas in economics is the Henry George principle of taxing the economic rent of land, and more generally, natural resources."[91] Stiglitz also claims that we now know land value tax "is even better than Henry George thought."

The Robert Schalkenbach Foundation publishes copies of George's works and related texts on economic reform and sponsors academic research into his policy proposals. The Lincoln Institute of Land Policy was founded to promote the ideas of Henry George but now focuses more generally on land economics and policy. The Henry George School of Social Science of New York and its satellite schools teach classes and conduct outreach.

Henry George theorem

In 1977, Joseph Stiglitz showed that under certain conditions, spending by the government on public goods will increase aggregate land rents by at least an equal amount. This result has been dubbed by economists the Henry George theorem, as it characterizes a situation where Henry George's "single tax" is not only efficient, it is also the only tax necessary to finance public expenditures.[92]

Economic contributions

George reconciled the issues of efficiency and equity, showing that both could be satisfied under a system in harmony with natural law.[93] He showed that Ricardo's Law of Rent applied not just to an agricultural economy, but even more so to urban economics. And he showed that there is no inherent conflict between labor and capital provided one maintained a clear distinction between classical factors of production, capital and land.

George developed what he saw as a crucial feature of his own theory of economics in a critique of an illustration used by Frédéric Bastiat in order to explain the nature of interest and profit. Bastiat had asked his readers to consider James and William, both carpenters. James has built himself a plane, and has lent it to William for a year. Would James be satisfied with the return of an equally good plane a year later? Surely not! He'd expect a board along with it, as interest. The basic idea of a theory of interest is to understand why. Bastiat said that James had given William over that year "the power, inherent in the instrument, to increase the productivity of his labor," and wants compensation for that increased productivity.[94]

George did not accept this explanation. He wrote, "I am inclined to think that if all wealth consisted of such things as planes, and all production was such as that of carpenters – that is to say, if wealth consisted but of the inert matter of the universe, and production of working up this inert matter into different shapes – that interest would be but the robbery of industry, and could not long exist."[95] But some wealth is inherently fruitful, like a pair of breeding cattle, or a vat of grape juice soon to ferment into wine. Planes and other sorts of inert matter (and the most lent item of all – money itself) earn interest indirectly, by being part of the same "circle of exchange" with fruitful forms of wealth such as those, so that tying up these forms of wealth over time incurs an opportunity cost.

George's theory had its share of critiques. Austrian school economist Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, for example, expressed a negative judgment of George's discussion of the carpenter's plane. In his treatise, Capital and Interest, he wrote:

(T)he separation of production into two groups, in one of which the vital forces of nature form a distinct element in addition to labour, while in the other they do not, is entirely untenable[...] The natural sciences have long ago told us that the cooperation of nature is universal. [...] The muscular movement of the man who planes would be of very little use, if the natural powers and properties of the steel edge of the plane did not come to his assistance.[96]

Later, George argued that the role of time in production is pervasive. In The Science of Political Economy, he writes:

[I]f I go to a builder and say to him, "In what time and at what price will you build me such and such a house?" he would, after thinking, name a time, and a price based on it. This specification of time would be essential.... This I would soon find if, not quarreling with the price, I ask him largely to lessen the time.... I might get the builder somewhat to lessen the time... ; but only by greatly increasing the price, until finally a point would be reached where he would not consent to build the house in less time no matter at what price. He would say [that the house just could not be built any faster]....The importance ... of this principle – that all production of wealth requires time as well as labor – we shall see later on; but the principle that time is a necessary element in all production we must take into account from the very first.[97]

According to Oscar B. Johannsen, "Since the very basis of the Austrian concept of value is subjective, it is apparent that George's understanding of value paralleled theirs. However, he either did not understand or did not appreciate the importance of marginal utility."[98]

Another spirited response came from British biologist T.H. Huxley in his article "Capital – the Mother of Labour," published in 1890 in the journal The Nineteenth Century. Huxley used the scientific principles of energy to undermine George's theory, arguing that, energetically speaking, labor is unproductive.[99]

Bibliography

- Our Land and Land Policy" 1871

- Progress and Poverty 1879 unabridged text (1912)

- The Land Question 1881 (The Irish Land Question)

- Social Problems 1883

- Protection or Free Trade 1886

- George, Henry (July 1887). "The New Party". The North American Review. University of Northern Iowa. 145 (368): 1–8. ISBN 0-85315-726-X.

- Protection or Free Trade 1886 unabridged text (1905)

- The Standard, New York 1887 to 1890 A weekly periodical started and usually edited by Henry George.

- The Condition of Labor" 1891

- A Perplexed Philosopher 1892

- The Science of Political Economy (unfinished) 1898

See also

- Geolibertarianism

- Georgism

- Charles Hall – An early precursor to Henry George

- Henry George Birthplace

- Henry George Theorem

- History of the board game Monopoly

- Land Value Tax

- Left-libertarianism

- Libertarian socialism

- New York City mayoral elections

- Spaceship Earth

- Tammany Hall#1870-1900

References

- Notes

- ↑ Greenslade, William (2005). Grant Allen : literature and cultural politics at the Fin de Siècle. Aldershot, Hants, England Burlington, VT: Ashgate. ISBN 0754608654.

- ↑ Barnes, Peter (2006). Capitalism 3.0 : a guide to reclaiming the commons. San Francisco Berkeley: Berrett-Koehler U.S. trade Bookstores and wholesalers, Publishers Group West. ISBN 1576753611.

- ↑ Becker, Gary. "Gary Becker Interview". Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ↑ Drewry, John E. (2010). Post Biographies Of Famous Journalists. Kessinger Publishing, LLC.

- ↑ Mace, Elisabeth. "The economic thinking of Jose Marti: Legacy foundation for the integration of America". Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ↑ Nearing, The Making of a Radical, pg. 29.

- ↑ Putz, Paul Emory. "Summer Book List: Henry George (and George Norris) and the Crisis of Inequality". Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ↑ Dictionary of American Biography, 1st. ed., s.v. "George, Henry," edited by Allen Johnson and Dumas Malone, Vol. VII (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1931), pp. 211–212.

- ↑ David Montgomery, American National Biography Online, s.v. "George, Henry," Feb. 2000, http://www.anb.org/articles/15/15-00261.html Accessed September 3, 2011

- 1 2 "American National Biography Online."

- ↑ Obituary, New York Times

- ↑ Richard F. George The Artist at Work

- ↑ "SINGLE TAXERS DINE JOHNSON; Medallion Made by Son of Henry George Presented to Cleveland's Former Mayor", The New York Times – May 31, 1910

- ↑ Formaini, Robert L. "Henry George Antiprotectionist Giant of American Economics" (PDF). Economic Insights of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. 10 (2). Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- ↑ Henry, George, JR. "The Life of Henry George," chap. 11.

- ↑ "George, Henry". http://www.encyclopedia.com/. International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. Retrieved 28 October 2014. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ Charles A. Barker, "Henry George and the California Background of Progress and Poverty," California Historical Society Quartery 24, no. 2 (Jun. 1945), 103–104.

- ↑ Dictionary of American Biography, s.v. "George, Henry," pp. 211–212.

- 1 2 3 Montgomery, American National Biography Online, s.v. "George, Henry," http://www.anb.org/articles/15/15-00261.html Accessed September 3, 2011.

- ↑ Obituary – The New York Times, May 4, 1897

- ↑ Agnes de Mille – Biography

- ↑ Peggy George (I) – Biography

- ↑ Agnes de Mille Papers, 1980–1993 : Biographical and Historical Note

- 1 2 Henry George, "What the Railroad Will Bring Us," Overland Monthly 1, no. 4 (Oct. 1868), http://www.grundskyld.dk/1-railway.html Accessed September 3, 2011.

- ↑ Dictionary of American Biography, s.v. "George, Henry," 213.

- ↑ Nock, Albert Jay. Henry George: Unorthodox American, Part IV.

- ↑ Jurgen G. Backhaus, "Henry George's Ingenious Tax: A Contemporary Restatement," American Journal of Economics and Sociology 56, no. 4 (Oct. 1997), 453–458

- ↑ Henry George, Progress and Poverty, (1879; reprinted, London: Kegan Paul, Tench & Co., 1886), 283–284.

- ↑ Charles A. Barker, "Henry George and the California Background of Progress and Poverty," California Historical Society Quartery 24, no. 2 (Jun. 1945), 97–115.

- ↑ According to his granddaughter Agnes de Mille, Progress and Poverty and its successors made Henry George the third most famous man in the USA, behind only Mark Twain and Thomas Edison.

- ↑ Dictionary of American Biography, s.v. "George, Henry," 214–215.

- ↑ Robert E. Weir, "A Fragile Alliance: Henry George and the Knights of Labor," American Journal of Economics and Sociology 56, no. 4 (Oct. 1997), 423–426.

- ↑ Dictionary of American Biography, s. V. "George, Henry," 215.

- ↑ Montgomery, American National Biography, s.v. "George, Henry," http://www.anb.org/articles/15/15-00261.html

- ↑ "Henry George's Death Abroad. London Papers Publish Long Sketches and Comment on His Career". New York Times. October 30, 1897. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

The newspapers today are devoting much attention to the death of Henry George, the candidate of the Jeffersonian Democracy for the office of Mayor of Greater New York, publishing long sketches of his career and philosophical and economical theories.

- ↑ Gabriel, Ralph (1946). Course of american democratic thought. p. 204.

- ↑ Yardley, Edmund (1905). Addresses at the funeral of Henry George, Sunday, October 31, 1897. Chicago: The Public publishing company. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- ↑ University of Chicago. Office of the President. Harper, Judson and Burton Administrations. Records, [Box 37, Folder 3], Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library

- ↑ "The Funeral Procession". The New York Times. November 1, 1897. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- 1 2 Lepore, Jill. "Forget 9-9-9. Here's a Simple Plan: 1". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- ↑ Henry George, Citizen of the World. By Anna George de Mille. Edited by Don C. Shoemaker. With an Introduction by Agnes de Mille. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1950.

- ↑ George, Henry (1879). "The True Remedy". Progress and Poverty: An Inquiry into the Cause of Industrial Depressions and of Increase of Want with Increase of Wealth. VI. New York: Robert Schalkenbach Foundation. ISBN 0-914016-60-1. Retrieved May 12, 2008.

- ↑ Lough, Alexandra. "The Last Tax: Henry George and the Social Politics of Land Reform in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era". Academia.edu.

George only sought to make land common property through the socialization of land rent, or what many have called the "unearned increment" of land value.

- ↑ Backhaus, "Henry George's Ingenious Tax," 453–458.

- ↑ "Supplement to Encyclopædia Britannica". 1889.

The labor vote in the election was trifling until Henry George had commenced an agitation for the nationalization of land.

- ↑ "The American: A National Journal, Volumes 15-16". 1888.

- ↑ "A RECEPTION TO MR.GEORGE.". The New York Times. 21 October 1882.

Mr. George expressed his thanks for the reception and predicted that soon the movement in favor of land nationalization would be felt all over the civilized world.

- ↑ George, Henry (1879). "How Equal Rights to the Land May Be Asserted and Secured". Progress and Poverty: An Inquiry into the Cause of Industrial Depressions and of Increase of Want with Increase of Wealth. VIII. New York: Robert Schalkenbach Foundation. ISBN 0-914016-60-1. Retrieved Nov 27, 2016.

- ↑ Armstrong, K. L. (1895). The Little Statesman: A Middle-of-the-road Manual for American Voters. Schulte Publishing Company. pp. 125–127. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- ↑ George, Henry (6 October 1886). "Throwing His Hat in the Ring: Henry George Runs for Mayor (Acceptance Speech)". New York World, New York Tribune, New York Star, and New York Times. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- ↑ Weir, "A Fragile Alliance," 425–425

- ↑ Henry George, Protection or Free Trade: An Examination of the Tariff Question, with Especial Regard to the Interests of Labor(New York: 1887).

- ↑ MacCallum, Spencer H. (Summer–Fall 1997). "The Alternative Georgist Tradition" (PDF). Fragments. 35. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ↑ Cowen, Tyler (May 1, 2009). "Anti-Capitalist Rerun". The American Interest. 4 (5). Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ↑ Lepore, Jill (October 13, 2008). "'Rock, Paper, Scissors: How we used to vote'". New Yorker. New Yorker.

- ↑ Saltman, Roy (2008). The history and politics of voting technology : chads and other scandals. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 97. ISBN 0230605982.

- ↑ For a more complete discussion of the adoption of the Australian Ballot, see Saltman, Roy G., (2006), The History and Politics of Voting Technology, Palgrave Macmillan, NY, pp. 96–103.

- ↑ "To illustrate: It is not the business of government to interfere with the views which any one may hold of the Creator or with the worship he may choose to pay him, so long as the exercise of these individual rights does not conflict with the equal liberty of others; and the result of governmental interference in this domain has been hypocrisy, corruption, persecution and religious war. It is not the business of government to direct the employment of labor and capital, and to foster certain industries at the expense of other industries; and the attempt to do so leads to all the waste, loss and corruption due to protective tariffs." "On the other hand it is the business of government to issue money. This is perceived as soon as the great labor saving invention of money supplants barter. To leave it to every one who chose to do so to issue money would be to entail general inconvenience and loss, to offer many temptations to roguery, and to put the poorer classes of society at a great disadvantage. These obvious considerations have everywhere, as society became well organized, led to the recognition of the coinage of money as an exclusive function of government. When in the progress of society, a further labor-saving improvement becomes possible by the substitution of paper for the precious metals as the material for money, the reasons why the issuance of this money should be made a government function become still stronger. The evils entailed by wildcat banking in the United States are too well remembered to need reference. The loss and inconvenience, the swindling and corruption that flowed from the assumption by each State of the Union of the power to license banks of issue ended with the war, and no -one would now go back to them. Yet instead of doing what every public consideration impels us to, and assuming wholly and fully as the exclusive function of the General Government the power to issue money, the private interests of bankers have, up to this, compelled us to the use of a hybrid currency, of which a large part, though guaranteed by the General Government, is issued and made profitable to corporations. The legitimate business of banking – the safekeeping and loaning of money, and the making and exchange of credits, is properly left to individuals and associations; but by leaving to them, even in part and under restrictions and guarantees, the issuance of money, the people of the United States suffer an annual loss of millions of dollars, and sensibly increase the influences which exert a corrupting effect upon their government." The Complete Works of Henry George. "Social Problems", p. 178, Doubleday Page & Co, New York, 1904

- ↑ Turner, Adair (April 13, 2012). "A new era for monetary policy". Berlin: INET. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- ↑ Hudson, Michael. "Scenarios for Recovery: How to Write Down the Debts and Restructure the Financial System" (PDF). Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- ↑ George, Henry. "Consequences of a Growing National Debt". Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- ↑ Brechin, Gray (2003). Indestructable By Reason of Beauty: The Beaumanance of a Public Library Building (PDF). Greenwood Press. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ↑ George, Henry (March 17, 1887). "Henry George on Woman Suffrage.". Providence Evening Telegram. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- ↑ The Single Tax Review Volume 15. New York: Publ. Off., 1915

- ↑ Altgeld, John (1899). Live Questions (PDF). Geo. S Bowen & Son. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ↑ Martí, José (2002). José Martí : selected writings. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0142437042.

- ↑ Buder, Stanley. Visionaries and Planners: The Garden City Movement and the Modern Community. New York: Oxford UP, 1990.

- ↑ Fox, Stephen R. "The Amateur Tradition: People and Politics." The American Conservation Movement: John Muir and His Legacy. Madison, WI: U of Wisconsin, 1985. 353.

- ↑ Bryan, William Jennings (October 30, 1897). "William Jennings Bryan: Henry George One of the World's Foremost Thinkers". The New York Times. The New York Times. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ↑ http://www.wealthandwant.com/HG/PP/Dewey_Appreciation_HG.html

- ↑ http://www.wealthandwant.com/docs/Nock_HGUA.htm

- ↑ A sermon that first appeared as No. VIII, Series 1944-45 of the Community Pulpit, published by The Community Church, New York, New York. Reprinted as a pamphlet by the Robert Schalkenbach Foundation <http://www.cooperative-individualism.org/holmes-john_henry-george-1945.html>

- ↑ Louis F. Post and Fred C. Leubusher, Henry George’s 1886 Campaign: An Account of the George-Hewitt Campaign in the New York Municipal Election of 1886 (New York: John W. Lovell Company, 1887)

- ↑ Sekirin, Peter (2006). Americans in conversation with Tolstoy : selected accounts, 1887-1923. Jefferson, N.C: McFarland. ISBN 078642253X.

- ↑ http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Henry_George.aspx

- ↑ Hobson, John A. (1897). "The Influence of Henry George in England". The Fortnightly. 68. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ↑ Henderson, Archibald. George Bernard Shaw, His Life and Works. London: Hurst and Blackett, 1911.

- ↑ "Wonder Woman at Massey Hall: Helen Keller Spoke to Large Audience Who Were Spellbound.". Toronto Star Weekly. January 1914. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ↑ "Progress & Poverty". Robert Schalkenbach Fdn..

- ↑ Mulvey, Paul (2002). "The Single-Taxers and the Future of Liberalism, 1906–1914". Journal of Liberal Democrat (34/35 Spring/Summer). Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ↑ Mulvey, Paul (2010). The political life of Josiah C. Wedgwood : land, liberty and empire, 1872-1943. Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK Rochester, NY: Boydell Press. ISBN 0861933087.

- ↑ Karl Marx – Letter to Friedrich Adolph Sorge in Hoboken

- ↑ Henry George's Thought

- ↑ L. Tolstoï. Où est l'issu? (1899) In Les Rayons de l’aube (Dernières études philosophiques). (Tr. J-W Bienstock) Paris; P.-V. Stock Éditeur, 1901, chap. xxiii, pp. 393-411.

- ↑ Wikisource:Letter on Henry George (I)

- ↑ Wikisource:Letter on Henry George (II)

- ↑ Wikisource:The Slavery of Our Times

- ↑ "Bill Moyers at the Howard Zinn Lecture". YouTube. 2010-11-12. Retrieved 2012-07-26.

- ↑ http://www.cooperative-individualism.org/einstein-albert_letters-to-anna-george-demille-1934.html

- ↑ Gaffney, Mason and Harrison, Fred. The Corruption of Economics. (London: Shepheard-Walwyn (Publishers) Ltd., 1994) ISBN 978-0-85683-244-4 (paperback).

- ↑ http://masongaffneyreader.com/quotes.htm

- ↑ Arnott, Richard J.; Joseph E. Stiglitz (Nov 1979). "Aggregate Land Rents, Expenditure on Public Goods, and Optimal City Size". Quarterly Journal of Economics. 93 (4): 471–500. doi:10.2307/1884466. JSTOR 1884466.

- ↑ http://masongaffney.org/essays/Henry_George_100_Years_Later.pdf

- ↑ Frédéric Bastiat, That Which is Seen, and That Which is Not Seen," 1850.

- ↑ Henry George, Progress and Poverty,, 161.

- ↑ Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, Capital and Interest: A Critical History of Economic Theory transl. William Smart (London: Macmillan and Co., 1890), 417.

- ↑ Henry George, The Science of Political Economy (New York: Doubleday & McClure Co., 1898), 369–370.

- ↑ Johannsen, Oscar B. Henry George and the Austrian economists. The American Journal of Economics and Sociology (Am. j. econ. sociol.) ISSN 0002-9246. Abstract.

- ↑ T.H. Huxley, "Capital – the Mother of Labour: An Economical Problem Discussed from a Physiological Point of View," The Nineteenth Century (Mar. 1890).

- Further reading

- Barker, Charles Albro Henry George. Oxford University Press 1955 and Greenwood Press 1974. ISBN 0-8371-7775-8

- George, Henry. (1881). Progress and Poverty: An Inquiry into the Cause of Industrial Depressions and of Increase of Want with Increase of Wealth; The Remedy. Kegan Paul (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2009; ISBN 978-1-108-00361-2)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Henry George. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Henry George |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Henry George |

- The Henry George Foundation (United Kingdom)

- Robert Schalkenbach Foundation

- Land Value Taxation Campaign (UK)

- The Henry George Foundation of Australia

- The Life of Henry George, by Henry George Jr, 1904

- Henry George (1839–1897). The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics. Library of Economics and Liberty (2nd ed.). Liberty Fund. 2008.

- The Center for the Study of Economics

- The Henry George Institute – Understanding Economics

- The Henry George School, founded 1932.

- Works by or about Henry George at Internet Archive

- Works by Henry George at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Online Works of Henry George

- Wealth and Want

- Prosper Australia

- Henry George at Find a Grave

- Henry George Foundation OnlyMelbourne

- The Complete Works of Henry George. Publisher: New York, Doubleday, Page & company, 1904. Description: 10 v. fronts (v. 1–9) ports. 21 cm. (searchable facsimile at the University of Georgia Libraries; DjVu & layered PDF format)

- The Crime of Poverty by Henry George

- Centro Educativo Internacional Henry George (Managua, Nicaragua), in Spanish

- The Economics of Henry George's "Progress and Poverty", by Edgar H. Johnson, 1910.