Hendecagon

| Regular hendecagon | |

|---|---|

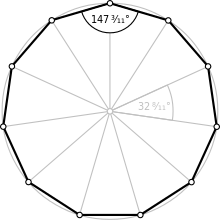

A regular hendecagon | |

| Type | Regular polygon |

| Edges and vertices | 11 |

| Schläfli symbol | {11} |

| Coxeter diagram |

|

| Symmetry group | Dihedral (D11), order 2×11 |

| Internal angle (degrees) | ≈147.273° |

| Dual polygon | Self |

| Properties | Convex, cyclic, equilateral, isogonal, isotoxal |

In geometry, a hendecagon (also undecagon [1][2] or endecagon[3]) or 11-gon is an eleven-sided polygon. (The name hendecagon, from Greek hendeka "eleven" and gon– "corner", is often preferred to the hybrid undecagon, whose first part is formed from Latin undecim "eleven".[4])

Regular hendecagon

A regular hendecagon is represented by Schläfli symbol {11}.

A regular hendecagon has internal angles of 147.27 degrees.[5] The area of a regular hendecagon with side length a is given by[2]

As 11 is not a Fermat prime, the regular hendecagon is not constructible with compass and straightedge.[6] Because 11 is not a Pierpont prime, construction of a regular hendecagon is still impossible even with the usage of an angle trisector. It can, however, be constructed via neusis construction.[7]

Close approximations to the regular hendecagon can be constructed, however. For instance, the ancient Greek mathematicians approximated the side length of a hendecagon inscribed in a unit circle as being 14/25 units long.[8]

Approximate construction

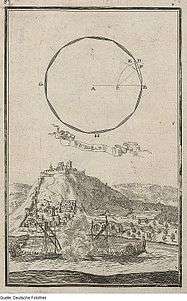

Corresponds to the copper engraving by Anton Ernst Burkhard of Birckenstein.

The following construction description is given by T. Drummond from 1800:[9]

- Draw the radius A B, bisect it in C—with an opening of the compasses equal to half the radius, upon A and C as centres describe the arcs C D I and A D—with the distance I D upon I describe the arc D O and draw the line C O, which will be the extent of one side of an endecagon sufficiently exact for practice.

On a unit circle:

- Constructed hendecagon side length

- Theoretical hendecagon side length

- Absolute error – if AB is 10 m then this error is approximately 2.3 mm.

Symmetry

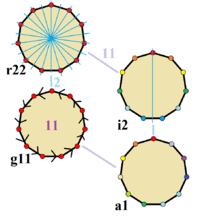

The regular hendecagon has Dih11 symmetry, order 22. Since 11 is a prime number there is one subgroup with dihedral symmetry: Dih1, and 2 cyclic group symmetries: Z11, and Z1.

These 4 symmetries can be seen in 4 distinct symmetries on the hendecagon. John Conway labels these by a letter and group order.[10] Full symmetry of the regular form is r22 and no symmetry is labeled a1. The dihedral symmetries are divided depending on whether they pass through vertices (d for diagonal) or edges (p for perpendiculars), and i when reflection lines path through both edges and vertices. Cyclic symmetries in the middle column are labeled as g for their central gyration orders.

Each subgroup symmetry allows one or more degrees of freedom for irregular forms. Only the g11 subgroup has no degrees of freedom but can seen as directed edges.

Use in coinage

The Canadian dollar coin, the loonie, is similar to, but not exactly, a regular hendecagonal prism,[11] as are the Indian 2-rupee coin[12] and several other lesser-used coins of other nations.[13] The cross-section of a loonie is actually a Reuleaux hendecagon. The United States Susan B. Anthony dollar has a hendecagonal outline along the inside of its edges.[14]

Related figures

The hendecagon shares the same set of 11 vertices with four regular hendecagrams:

{11/2} |

{11/3} |

{11/4} |

{11/5} |

See also

- 10-simplex - can be seen as a complete graph in a regular hendecagonal orthogonal projection

References

- ↑ Haldeman, Cyrus B. (1922), "Construction of the regular undecagon by a sextic curve", Discussions, American Mathematical Monthly, 29 (10), JSTOR 2299029.

- 1 2 Loomis, Elias (1859), Elements of Plane and Spherical Trigonometry: With Their Applications to Mensuration, Surveying, and Navigation, Harper, p. 65.

- ↑ Brewer, Ebenezer Cobham (1877), Errors of speech and of spelling, London: W. Tegg and co., p. iv.

- ↑ Hendecagon – from Wolfram MathWorld

- ↑ McClain, Kay (1998), Glencoe mathematics: applications and connections, Glencoe/McGraw-Hill, p. 357, ISBN 9780028330549.

- ↑ As Gauss proved, a polygon with a prime number p of sides can be constructed if and only if p − 1 is a power of two, not true for 11. See Kline, Morris (1990), Mathematical Thought From Ancient to Modern Times, 2, Oxford University Press, pp. 753–754, ISBN 9780199840427.

- ↑ BENJAMIN, ELLIOT; SNYDER, C. Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society156.3 (May 2014): 409-424.; http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0305004113000753

- ↑ Heath, Sir Thomas Little (1921), A History of Greek Mathematics, Vol. II: From Aristarchus to Diophantus, The Clarendon Press, p. 329.

- ↑ T. Drummond, (1800) The Young Ladies and Gentlemen's AUXILIARY, in Taking Heights and Distances ..., Construction description pp. 15–16 Fig. 40: scroll from page 69 ... to page 76 Part I. Second Edition, retrieved on 26th March 2016

- ↑ John H. Conway, Heidi Burgiel, Chaim Goodman-Strauss, (2008) The Symmetries of Things, ISBN 978-1-56881-220-5 (Chapter 20, Generalized Schaefli symbols, Types of symmetry of a polygon pp. 275-278)

- ↑ Mossinghoff, Michael J. (2006), "A $1 problem" (PDF), American Mathematical Monthly, 113 (5): 385–402, doi:10.2307/27641947, JSTOR 27641947

- ↑ Cuhaj, George S.; Michael, Thomas (2012), 2013 Standard Catalog of World Coins 2001 to Date, Krause Publications, p. 402, ISBN 9781440229657.

- ↑ Cuhaj, George S.; Michael, Thomas (2011), Unusual World Coins (6th ed.), Krause Publications, pp. 23, 222, 233, 526, ISBN 9781440217128.

- ↑ U.S. House of Representatives, 1978, p. 7.

External links

- Properties of an Undecagon (hendecagon) With interactive animation

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Hendecagon". MathWorld.