Heart transplantation

| Heart transplantation | |

|---|---|

| Intervention | |

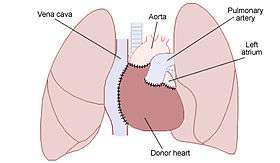

Diagram illustrating the placement of a donor heart in an orthotopic procedure. Notice how the back of the patient's left atrium and great vessels are left in place. | |

| ICD-9-CM | 37.51 |

| MeSH | D016027 |

| MedlinePlus | 003003 |

A heart transplant, or a cardiac transplant, is a surgical transplant procedure performed on patients with end-stage heart failure or severe coronary artery disease when other medical or surgical treatments have failed. As of 2016, the most common procedure is to take a functioning heart (with or without transplantation of a lung or lungs; a cadaveric donor cardiectomy) from a recently deceased organ donor (the cadaveric allograft), and implant it into the patient. The patient's own heart is either removed (the cardiectomy for the recipient) and replaced with the donor heart (orthotopic procedure) or, less commonly, the recipient's diseased heart is left in place to support the donor heart (heterotopic procedure). Approximately 3500 heart transplants are performed every year in the world, more than half of which occur in the US.[1] Post-operation survival periods average 15 years.[2] Heart transplantation is not considered to be a cure for heart disease, but a life-saving treatment intended to improve the quality of life for recipients.[3]

History

One of the first mentions of the possibility of heart transplantation was by American medical researcher Simon Flexner, who declared in a reading of his paper on “Tendencies in Pathology” in the University of Chicago in 1907 that it would be possible in the then-future for diseased human organs substitution for healthy ones by surgery — including arteries, stomach, kidneys and heart.[4]

Norman Shumway is widely regarded as the father of heart transplantation although the world's first adult human heart transplant was performed by a South African cardiac surgeon, Christiaan Barnard, utilizing the techniques developed and perfected by Shumway and Richard Lower.[5] Barnard performed the first transplant on Louis Washkansky on December 3, 1967, at the Groote Schuur Hospital in Cape Town, South Africa.[5][6] Adrian Kantrowitz performed the world's first pediatric heart transplant on December 6, 1967, at Maimonides Hospital in Brooklyn, New York, barely three days after Christiaan Barnard's pioneering operation.[5] Since the 19-day-old infant died little more than six hours after receiving the heart, this operation was considered a failure.[7]Norman Shumway performed the first adult heart transplant in the United States on January 6, 1968, at the Stanford University Hospital.[5]

Worldwide, about 3,500 heart transplants are performed annually. The vast majority of these are performed in the United States (2,000–2,300 annually).[1] Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, California, currently is the largest heart transplant center in the world, having performed 132 adult transplants in 2015[8] alone. About 800,000 people have NYHA Class IV heart failure symptoms indicating advanced heart failure.[9] The great disparity between the number of patients needing transplants and the number of procedures being performed spurred research into the transplantation of non-human hearts into humans after 1993. Xenografts from other species and man-made artificial hearts are two less successful alternatives to allografts.[2]

Most published surgical methods of HT necessarily divide the Vagus nerve and thus amputate parasympathetic control of the myocardium.[10]

Contraindications

Some patients are less suitable for a heart transplant, especially if they suffer from other circulatory conditions related to their heart condition. The following conditions in a patient increase the chances of complications;

Absolute contraindications:

- Advanced kidney, lung, or liver disease

- Active cancer if it is likely to impact the survival of the patient

- Life-threatening diseases unrelated to heart failure including acute infection or systemic disease such as systemic lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, or amyloidosis

- Vascular disease of the neck and leg arteries.

- High pulmonary vascular resistance - over 5 or 6 Wood units.

Relative contraindications:

- Insulin-dependent diabetes with severe organ dysfunction

- Recent thromboembolism such as stroke

- Severe obesity

- Age over 65 years (some variation between centers) - older patients are usually evaluated on an individual basis.

- Active substance abuse, such as alcohol, recreational drugs or tobacco smoking (which increases the chance of lung disease)

Patients who are in need of a heart transplant but do not qualify, may be candidates for an artificial heart [1] or a left ventricular assist device i.e. LVAD.

Complications

Post-operative complications include infection, sepsis, organ rejection, as well as the side-effects of the immunosuppressive medication. Since the transplanted heart originates from another organism, the recipient's immune system typically attempts to reject it. The risk of rejection never fully goes away, and the patient will be on immunosuppressive drugs for the rest of his or her life, but these may cause unwanted side effects, such as increased likelihood of infections or development of certain cancers. Recipients can acquire kidney disease from a heart transplant due to side effects of immunosuppressant medications. Many recent advances in reducing complications due to tissue rejection stem from mouse heart transplant procedures.[12] Surgery death rate is 5-10% in 2011.[13]

Prognosis

The prognosis for heart transplant patients following the orthotopic procedure has increased over the past 20 years, and as of June 5, 2009, the survival rates were:[14]

- 1 year: 88.0% (males), 86.2% (females)

- 3 years: 79.3% (males), 77.2% (females)

- 5 years: 73.2% (males), 69.0% (females)

In a study spanning 1999 to 2007, conducted on behalf of the U.S. federal government by Dr. Eric Weiss of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, it was discovered that, compared to men receiving male hearts, "men receiving female hearts had a 15% increase in the risk of adjusted cumulative mortality" over five years. No significant differences were noted with females receiving hearts from male or female donors.[15]

Famous recipients

- Robert Altman (1925-2006), American film director (M*A*S*H, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, Nashville), transplant in 1995 (survival: 11 years)

- Robert P. Casey (1932-2000), American politician (42nd Governor of Pennsylvania), transplant in 1993 (survival: 7 years)

- Dick Cheney (born 1941), American politician (46th Vice President of the United States), transplant in 2012

- Erik Compton (born 1979), Norwegian-American golfer, transplants in 1992 and 2008

- Glen Gondrezick (1955-2009), American basketball player (New York Knicks, Denver Nuggets), transplant in 2008 (survival: <1 year)

- Jonathan Hardy (1940-2012), Australian actor, writer and director (The Devil's Playground, Mad Max, Mr. Reliable, Moulin Rouge!), transplant in 1988 (survival: 24 years)

- Billy T. James (1948-1991), New Zealand comedian (The Billy T James Show), transplant in 1989 (survival: 2 years)

- Eddie Large (born 1941), British comedian (Little and Large), transplant in 2002

- Mussum (1941-1994), Brazilian comedian and actor (Os Trapalhões), transplant in 1994 (survival: <1 year)

- Norton Nascimento (1962-2007), Brazilian actor, transplant in 2003 (survival: 4 years)

- Kelly Perkins (born 1961), American mountain climber, transplant in 1995

- Jerry Richardson (born 1936), American football player (Baltimore Colts) and team owner (Carolina Panthers), transplant in 2009

- Sandro de América (1945-2009), Argentinian singer, transplant in 2008 (survival: <1 year)[16]

- Sam Wyche (born 1945), NFL player 1968-1976 and Head Coach, (Cincinnati Bengals 1984-1991), (Tampa Bay Buccaneers 1992-1995), transplant in 2016[17]

Other notable recipients

At the time of his death on August 10, 2009, Tony Huesman was the world's longest living heart transplant recipient, having survived for 30 years, 11 months and 10 days, before dying of cancer.[18] Huesman received a heart in 1978 at the age of 20 after viral pneumonia severely weakened his heart.[19] The operation was performed at Stanford University under Dr. Norman Shumway.[20]

As of February 2016, the record holder for longest living heart recipient was Englishman John McCafferty. He received his heart on 20 October 1982.[18] He died aged 73 on 9 February 2016, 33 years after his operation. The operation was performed at Harefield Hospital in Middlesex under Sir Magdi Yacoub.[21]

Former Vice President of the United States Dick Cheney received a heart transplant on March 24, 2012.[22] Because he was 71 years old at the time of the surgery, it sparked discussions about the upper age of transplant patients.[23]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Cook JA, Shah KB, Quader MA, et al. The total artificial heart. Journal of Thoracic Disease. 2015;7(12):2172-2180. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.10.70.

- 1 2 Till Lehmann (director) (2007). The Heart-Makers: The Future of Transplant Medicine (documentary film). Germany: LOOKS film and television.

- ↑ Burch M.; Aurora P. (2004). "Current status of paediatric heart, lung, and heart-lung transplantation". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 89 (4): 386–389. doi:10.1136/adc.2002.017186. PMC 1719883

. PMID 15033856.

. PMID 15033856. - ↑ MAY TRANSPLANT THE HUMAN HEART (.PDF), The New York Times, January 2, 1908.

- 1 2 3 4 McRae, D. (2007). Every Second Counts. Berkley.

- ↑ "Memories of the Heart". Doylestown, Pennsylvania: Daily Intelligencer. November 29, 1987. p. A–18.

- ↑ Lyons, Richard D. "Heart Transplant Fails to Save 2-Week-old Baby in Brooklyn; Heart Transplant Fails to Save Baby Infants' Surgery Harder Working Side by Side Gives Colleague Credit", The New York Times, December 7, 1967. Accessed November 19, 2008.

- ↑ "SRTR -- Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients". www.srtr.org. Retrieved 2016-10-24.

- ↑ Reiner Körfer (interviewee) (2007). The Heart-Makers: The Future of Transplant Medicine (documentary film). Germany: LOOKS film and television.

- ↑ Arrowood, James A.; Minisi, Anthony J.; Goudreau, Evelyne; Davis, Annette B.; King, Anne L. (1997-11-18). "Absence of Parasympathetic Control of Heart Rate After Human Orthotopic Cardiac Transplantation". Circulation. 96 (10): 3492–3498. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.96.10.3492. ISSN 0009-7322. PMID 9396446.

- ↑ Mehra MR, Canter CE, Hannan MM, Semigran MJ, Uber PA, et al. The 2016 International Society for Heart Lung Transplantation listing criteria for heart transplantation: A 10-year update. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2016 Jan. 35 (1):1-23.

- ↑ Bishay R (2011). "The 'Mighty Mouse' Model in Experimental Cardiac Transplantation". Hypothesis. 9 (1): e5. doi:10.5779/hypothesis.v9i1.205.

- ↑ Jung SH, Kim JJ, Choo SJ, Yun TJ, Chung CH, Lee JW (2011). "Long-term mortality in adult orthotopic heart transplant recipients". J. Korean Med. Sci. 26: 599–603. doi:10.3346/jkms.2011.26.5.599. PMC 3082109

. PMID 21532848.

. PMID 21532848. - ↑ Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics--2012 Update The American Heart Association. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ↑ Weiss, E. S.; Allen, J. G.; Patel, N. D.; Russell, S. D.; Baumgartner, W. A.; Shah, A. S.; Conte, J. V. (2009). "The Impact of Donor-Recipient Sex Matching on Survival After Orthotopic Heart Transplantation: Analysis of 18 000 Transplants in the Modern Era". Circulation: Heart Failure. 2 (5): 401–408. doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.844183.

- ↑ "A los 64 años, falleció Sandro". Infobae (in Spanish). 5 January 2010. Archived from the original on 8 January 2010.

- ↑ Keeler, Scott (September 13, 2016). "Furman Hall of Famer Wyche in recovery after transplant". The Greenville News.

- 1 2 Prynne, Miranda (24 December 2013). "Brit sets new record for longest surviving heart transplant patient". The Daily Telegraph. United Kingdom. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ↑ http://www.columbusdispatch.com/live/content/local_news/stories/2009/08/10/aheart.html?sid=101

- ↑ Heart Transplant Patient OK After 28 Yrs (14 September 2006) CBS News. Retrieved 29 December 2006.

- ↑ "Guinness World Record heart transplant patient dies". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ↑ "Cheney undergoes heart transplant surgery". Fox News. 24 March 2012.

- ↑ OLIVIA KATRANDJIAN (March 25, 2012). "Is Dick Cheney Too Old for a Heart Transplant? -". ABC News. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

External links

- - Heart Transplant in India

- - The real first heart transplant.

- Official Heart Transplant Museum - Heart Of Cape Town

- Photograph of first U.S. heart transplant

- Western Cape government; South Africa (21 February 2005). "Chris Barnard Performs World's First Heart Transplant". Cape Gateway. Retrieved 2007-01-10.

- Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery. "Patient's Guide to Heart Transplant Surgery". University of Southern California. Retrieved 2007-01-10.

- Nancy Reid (22 September 2005). "Heart transplant: How is it performed?". Healthwise. Retrieved 2007-01-10.

- The Adrian Kantrowitz Papers Profiles in Science from the National Library of Medicine for Adrian Kantrowitz, the first to perform a pediatric heart transplant

- Orthotopic heart transplantation: the bicaval technique