Health (gaming)

Health is an attribute assigned to entities within a role-playing or video game that indicates its state in combat.[1] Health is usually measured in hit points or health points, often shortened as HP. When the HP of a player character reaches zero, the player may lose a life or their character might become incapacitated or die. When the HP of an enemy reaches zero, the player might be rewarded in some way.

Any entity within a game could have a health value, including the player character, non-player characters and objects. Indestructible entities have no diminishable health value.

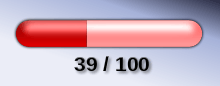

Health might be displayed as a numeric value, such as "50/100". Here, the first number indicates the current amount of HP an entity has and the second number indicates the entity's maximum HP. In video games, health can also be displayed graphically, such as with a bar that empties itself when an entity loses health (a health bar), icons that are "chipped away" from, or in more novel ways.[2][3]

History

Dungeons & Dragons co-creator Dave Arneson described the origin of hit points in a 2002 interview. When Arneson was adapting the medieval wargame Chainmail (1971) to a fantasy setting, a process that with Gary Gygax would lead to Dungeons & Dragons, he saw that the emphasis of the gameplay was moving from large armies to small groups of heroes and eventually to the identification of one player and one character that is essential to role-playing as it was originally conceived. Players became attached to their heroes and did not want them to die every time they lost a die roll. Players were thus given multiple hit points which were incrementally decreased as they took damage. Arneson took the concept, along with armor class, from a set of a naval American Civil War game's rules.[4]

One of the first games to use a visual health meter was Namco's 1984 video game Dragon Buster. This allowed players in action games to withstand multiple hits before losing a life and for different enemies to deal different amounts of damage.[5] A visual power meter representing stamina was also used earlier in Nintendo's 1983 arcade game Punch-Out!![6] and Data East's 1981 DECO Cassette System arcade game Flash Boy.[7]

Usage

In action video games as well as in role-playing games, health points can usually be depleted by attacking the entity. A defense attribute might reduce the amount of HP that is lost when a character is damaged. It is common in role-playing games for a character's maximum health and defense attributes to be gradually raised as the character levels up.[8] In game design, it is deemed important that a player is aware of it when they are losing health, each hit playing a clear sound effect. Author Scott Rogers states that "health should deplete in an obvious manner, because with every hit, a player is closer to losing their life."[3] The display of health also helps to dramatize the near-loss of a life.[9]

Regenerating health

Player characters can often restore their health points by consuming certain items, such as health potions, food or first-aid kits.[1] Staying a night at an inn fully restores a character's health in many role-playing video games.[10] In general, the different methods of regenerating health has its uses in a particular genre. In action games, this method is very quick, whereas role-playing games feature slower paced methods to match the gameplay and realism.[9]

Some video games feature automatically regenerating health, where lost health points are regained over time. This can be useful to not "cripple" the player, making them still able to continue even after losing lots of health. However, automatically regenerating health may also cause a player to "power through" sections they might otherwise have had to approach cautiously, simply because there are no lasting consequences to losing a large amount of health.[11]

This mechanic initially appeared in action role-playing games, with early examples popularizing the mechanic including Hydlide and the Ys series.[12][13] In these games, the player character has to stand still for their health to automatically regenerate.[14] This system was popularized in first-person shooters by Halo: Combat Evolved (2001),[3] though regenerating health in The Getaway (2002) has been cited to be more comparable to later use of the mechanic in first-person shooters.[12]

Display

The way health is displayed on the screen has an effect on the player. Many games only show the health of the player character, while keeping the health of enemies hidden. This is done in the Legend of Zelda series and Monster Hunter series to keep the player's progress in defeating their enemy unclear and therefore exciting. In these games, the fact that the enemies are being damaged is indicated by their behavior.[15] On the other hand, fighting games like the Street Fighter series use easy-to-read health bars to clearly indicate the progress the player is making with each hit.[16]

It is common in first-person shooters to indicate low health of the player character by blood spatters or by a distorted red hue on the screen, attempting to mimic the effects of wounding and trauma. These visual effects fade as health regenerates.[17]

References

- 1 2 Moore, Michael (2011-03-23). Basics of Game Design. CRC Press. pp. 151, 194. ISBN 1439867763. Retrieved 2014-12-09.

- ↑ Chris Antista. "The 10 most creative life bars.". GamesRadar. 2010-08-17. p. 2. Archived from the original on 2015-12-28.

- 1 2 3 Rogers, Scott (2010-09-29). Level Up!: The Guide to Great Video Game Design. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 276–277. ISBN 0470970928. Retrieved 2014-11-21.

- ↑ Allen Rausch (2004-08-19). "Dave Arneson Interview.". GameSpy. Retrieved 2014-01-09.

- ↑ "Gaming's most important evolutions". GamesRadar. Oct 8, 2010. p. 4. Retrieved 2011-03-29.

- ↑ "Glass Joe Boxes Clever". Computer+Video Games. Future Publishing: 47. August 1984. Retrieved 2015-01-02.

- ↑ John Szczepaniak, History of Japanese Video Games, Kinephanos, ISSN 1916-985X

- ↑ Nickogibson (2012-09-12). "What is an RPG - Intro to RPG Games". Slideshare. Retrieved 2015-01-09.

- 1 2 Fullerton, Tracy (2008-02-08). Game Design Workshop: A Playcentric Approach to Creating Innovative Games. CRC Press. pp. 72, 73. ISBN 0240809742. Retrieved 2014-12-19.

- ↑ Duggan, Michael (2011). RPG Maker for Teens. Cengage Learning. pp. 109, 141. ISBN 1435459679. Retrieved 2014-12-09.

- ↑ Jonathan Moriarty (2010-12-02). "Video Game Basics: The Health Bar". Baltimoregamer.com. Archived from the original on 28 April 2012. Retrieved 2014-11-21.

- 1 2 Dunn, Jeff (2012-11-15). "Stop, Drop, and Heal: The history of regenerating health". GamesRadar. Retrieved 2015-01-08.

- ↑ Sulliven, Lucas. "Top 7… Games you didn't know did it first". GamesRadar. Retrieved 2015-01-08.

- ↑ Szczepaniak, John (7 July 2011). "Falcom: Legacy of Ys". GamesTM (111): 152–159 [153].(cf. Szczepaniak, John (July 8, 2011). "History of Ys interviews". Hardcore Gaming 101. Retrieved 6 September 2011.)

- ↑ Jon Martindale (2012-10-03). "Let's Kill off Health Bars". Kit Guru Gaming. Archived from the original on May 28, 2015. Retrieved 2014-11-21.

- ↑ Novak, Jeannie (2013-04-11). The Official GameSalad Guide to Game Development. Cengage Learning. p. 31. ISBN 1133605648. Retrieved 2014-11-21.

- ↑ Voorhees, Gerald A.; Call, Joshua; Whitlock, Katie (2012-11-02). "Disposable Bodies:Cyborg Regeneration and FPS Mechanics". Guns, Grenades, and Grunts: First-Person Shooter Games (Google eBook). Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 1441191445. Retrieved 2014-11-21.