Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump

| Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump | |

|---|---|

|

Native name | |

|

The cliffs at Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump | |

| Location |

Municipal District of Willow Creek No. 26 near Fort Macleod Alberta |

| Coordinates | 49°44′58″N 113°37′30″W / 49.74944°N 113.62500°WCoordinates: 49°44′58″N 113°37′30″W / 49.74944°N 113.62500°W |

| Area | 73.29 square kilometres (28.30 sq mi) |

| Founded | 1955 |

| Governing body | Alberta Community Development |

IUCN Category III (Natural Monument) | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | vi |

| Designated | 1981 (5th session) |

| Reference no. | 158 |

| Country | Canada |

| Region | Europe and North America |

| Official name: Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump National Historic Site of Canada | |

| Designated | 1968 |

| Type | Provincial Historic Site |

| Designated | 1979 |

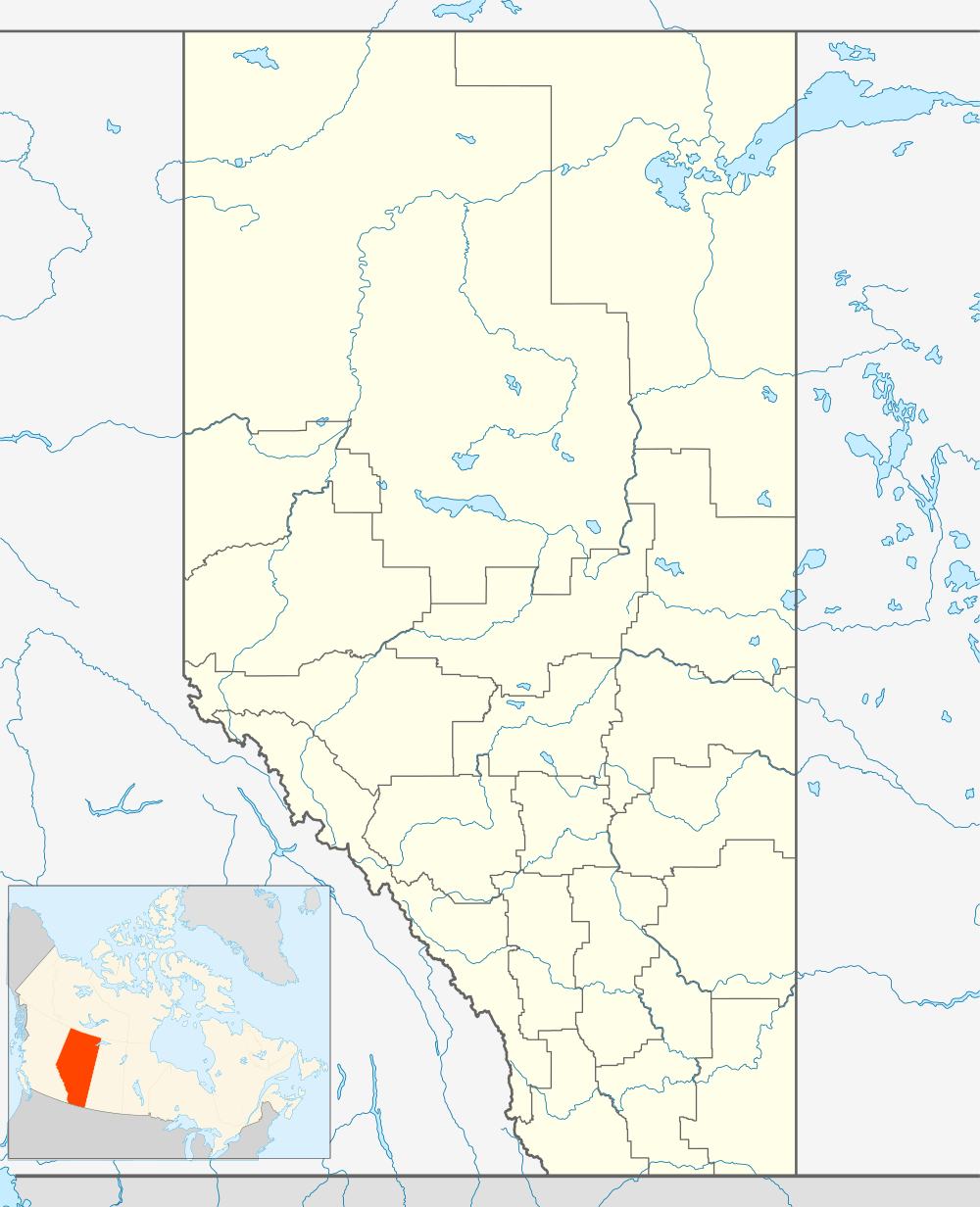

Location of Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump in Alberta | |

Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump is a buffalo jump located where the foothills of the Rocky Mountains begin to rise from the prairie 18 km northwest of Fort Macleod, Alberta, Canada on highway 785. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and home of a museum of Blackfoot culture. Joe Crowshoe Sr. OC (1903 - 1999) - Aapohsoy’yiis (Weasel Tail) - a ceremonial Elder of the Piikani Nation in southern Alberta - was instrumental in the development of the Site. The Joe Crow Shoe Sr. Lodge is dedicated to his memory. He dedicated his life to preserving Aboriginal culture and promoting the relationship between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people and in 1998 was awarded the National Aboriginal Achievement Award for "saving the knowledge and practices of the Blackfoot people."[1]

History

The buffalo jump was used for 5,500 years by the indigenous peoples of the plains to kill buffalo by driving them off the 11 metre (36 foot) high cliff. Before the late introduction of horses, the Blackfoot drove the buffalo from a grazing area in the Porcupine Hills about 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) west of the site to the "drive lanes", lined by hundreds of cairns, by dressing up as coyotes and wolves. These specialized "buffalo runners" were young men trained in animal behavior to guide the buffalo into the drive lanes. Then, at full gallop, the buffalo would fall from the weight of the herd pressing behind them, breaking their legs and rendering them immobile. The cliff itself is about 300 metres (1000 feet) long, and at its highest point drops 10 metres into the valley below. The site was in use at least 6,000 years ago, and the bone deposits are 12 metres (39 feet) deep. After falling off the cliff, the buffalo carcasses were processed at a nearby camp. The camp at the foot of the cliffs provided the people with everything they needed to process a buffalo carcass, including fresh water. The majority of the buffalo carcass was used for a variety of purposes, from tools made from the bone, to the hide used to make dwellings and clothing. The importance of the site goes beyond just providing food and supplies. After a successful hunt, the wealth of food allowed the people to enjoy leisure time and pursue artistic and spiritual interests. This increased the cultural complexity of the society.

In Blackfoot, the name for the site is Estipah-skikikini-kots. According to legend, a young Blackfoot wanted to watch the buffalo plunge off the cliff from below, but was buried underneath the falling buffalo. He was later found dead under the pile of carcasses, where he had his head smashed in.[2]

World Heritage Site

Head-Smashed-In was abandoned in the 19th century after European contact. The site was first recorded by Europeans in the 1880s, and first excavated by the American Museum of Natural History in 1938. It was designated a National Historic Site in 1968, a Provincial Historic Site in 1979, and a finally a World Heritage Site in 1981 for its testimony of prehistoric life and the customs of aboriginal people.[3]

Interpretive centre and museum

Opened in 1987, the interpretive centre at Head-Smashed-In is built into the ancient sandstone cliff in naturalistic fashion. It contains five distinct levels depicting the ecology, mythology, lifestyle and technology of Blackfoot peoples within the context of available archaeological evidence, presented from the viewpoints of both aboriginal peoples and European archaeological science.

The centre also offers tipi camping and hands-on educational workshops in facets of First Nations life, such as making moccasins, drums, etc. Each year Head-Smashed-In hosts a number of special events and native festivals known throughout the world for their color, energy and authenticity, including a special Christmas festival called Heritage Through My Hands, which brings together First Nations artists and craftspeople who display a wide variety of jewelry, clothing, art and crafts. Visitors can witness traditional drumming and dancing demonstrations every Wednesday from July to August at 11 a.m and 1:30 p.m. at the centre.

There is now a permanent exhibition at Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump. Lost Identities: A Journey of Rediscovery made its first appearance here in 1999, but now it is back to stay. The exhibition, is a collaboration of many historical societies and museums that have given voice to otherwise silent photographs. These photographs have been unidentified for some time. But "the exhibit travel led to the Aboriginal communities" finding the voice and story behind the photographs taken in these communities.

The facility was designed by Le Blond Partnership, an architectural firm in Calgary. The design was awarded the Governor General's Gold Medal for Architecture in 1990.[4][5]

See also

References

Archaeology of Native North America, 2010, Dean R. Snow, Prentice-Hall, New York.

- ↑ http://history.alberta.ca/headsmashedin/about/about.aspx#3

- ↑ "Legend of Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump". Bison in Mythology and Religious Ritual. University of Calgary, the Applied History Research Group. 1997. Retrieved 2012-07-14.

- ↑ UNESCO. "Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump". Retrieved 2006-01-10.

- ↑ The Architecture - History Alberta webpage. Retrieved 2014-02-05

- ↑ RAIC Awards and Honours, past recipients. Retrieved 2014-02-05