Hawking radiation

Hawking radiation is blackbody radiation that is predicted to be released by black holes, due to quantum effects near the event horizon. It is named after the physicist Stephen Hawking, who provided a theoretical argument for its existence in 1974,[1] and sometimes also after Jacob Bekenstein, who predicted that black holes should have a finite, non-zero temperature and entropy.[2]

Hawking's work followed his visit to Moscow in 1973 where the Soviet scientists Yakov Zeldovich and Alexei Starobinsky showed him that, according to the quantum mechanical uncertainty principle, rotating black holes should create and emit particles.[3] Hawking radiation reduces the mass and energy of black holes and is therefore also known as black hole evaporation. Because of this, black holes that do not gain mass through other means are expected to shrink and ultimately vanish. Micro black holes are predicted to be larger net emitters of radiation than larger black holes and should shrink and dissipate faster.

In June 2008, NASA launched the Fermi space telescope, which is searching for the terminal gamma-ray flashes expected from evaporating primordial black holes. In the event that speculative large extra dimension theories are correct, CERN's Large Hadron Collider may be able to create micro black holes and observe their evaporation.[4][5][6][7]

In September 2010, a signal that is closely related to black hole Hawking radiation (see analog gravity) was claimed to have been observed in a laboratory experiment involving optical light pulses. However, the results remain unverified and debatable.[8][9] Other projects have been launched to look for this radiation within the framework of analog gravity.

Overview

| General relativity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

|

Fundamental concepts |

||||||

|

||||||

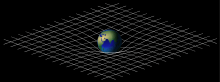

Black holes are sites of immense gravitational attraction. Classically, the gravitation is so powerful that nothing, not even electromagnetic radiation, can escape from the black hole. It is yet unknown how gravity can be incorporated into quantum mechanics. Nevertheless, far from the black hole the gravitational effects can be weak enough for calculations to be reliably performed in the framework of quantum field theory in curved spacetime. Hawking showed that quantum effects allow black holes to emit exact black body radiation. The electromagnetic radiation is produced as if emitted by a black body with a temperature inversely proportional to the mass of the black hole.

Physical insight into the process may be gained by imagining that particle–antiparticle radiation is emitted from just beyond the event horizon. This radiation does not come directly from the black hole itself, but rather is a result of virtual particles being "boosted" by the black hole's gravitation into becoming real particles.[10] As the particle–antiparticle pair was produced by the black hole's gravitational energy, the escape of one of the particles lowers the mass of the black hole.[11]

An alternative view of the process is that vacuum fluctuations cause a particle–antiparticle pair to appear close to the event horizon of a black hole. One of the pair falls into the black hole while the other escapes. In order to preserve total energy, the particle that fell into the black hole must have had a negative energy (with respect to an observer far away from the black hole). This causes the black hole to lose mass, and, to an outside observer, it would appear that the black hole has just emitted a particle. In another model, the process is a quantum tunnelling effect, whereby particle–antiparticle pairs will form from the vacuum, and one will tunnel outside the event horizon.[10]

An important difference between the black hole radiation as computed by Hawking and thermal radiation emitted from a black body is that the latter is statistical in nature, and only its average satisfies what is known as Planck's law of black body radiation, while the former fits the data better. Thus thermal radiation contains information about the body that emitted it, while Hawking radiation seems to contain no such information, and depends only on the mass, angular momentum, and charge of the black hole (the no-hair theorem). This leads to the black hole information paradox.

However, according to the conjectured gauge-gravity duality (also known as the AdS/CFT correspondence), black holes in certain cases (and perhaps in general) are equivalent to solutions of quantum field theory at a non-zero temperature. This means that no information loss is expected in black holes (since the theory permits no such loss) and the radiation emitted by a black hole is probably the usual thermal radiation. If this is correct, then Hawking's original calculation should be corrected, though it is not known how (see below).

A black hole of one solar mass (M☉) has a temperature of only 60 nanokelvins (60 billionths of a kelvin); in fact, such a black hole would absorb far more cosmic microwave background radiation than it emits. A black hole of 4.5×1022 kg (about the mass of the Moon, or about 13 µm across) would be in equilibrium at 2.7 K, absorbing as much radiation as it emits. Yet smaller primordial black holes would emit more than they absorb and thereby lose mass.[10]

Trans-Planckian problem

The trans-Planckian problem is the observation that Hawking's original calculation requires talking about quantum particles in which the wavelength becomes shorter than the Planck length near the black hole's horizon. It is due to the peculiar behavior near a gravitational horizon where time stops as measured from far away. A particle emitted from a black hole with a finite frequency, if traced back to the horizon, must have had an infinite frequency there and a trans-Planckian wavelength.

The Unruh effect and the Hawking effect both talk about field modes in the superficially stationary space-time that change frequency relative to other coordinates which are regular across the horizon. This is necessarily so, since to stay outside a horizon requires acceleration which constantly Doppler shifts the modes.

An outgoing Hawking radiated photon, if the mode is traced back in time, has a frequency which diverges from that which it has at great distance, as it gets closer to the horizon, which requires the wavelength of the photon to "scrunch up" infinitely at the horizon of the black hole. In a maximally extended external Schwarzschild solution, that photon's frequency only stays regular if the mode is extended back into the past region where no observer can go. That region seems to be unobservable and is physically suspect, so Hawking used a black hole solution without a past region which forms at a finite time in the past. In that case, the source of all the outgoing photons can be identified: a microscopic point right at the moment that the black hole first formed.

The quantum fluctuations at that tiny point, in Hawking's original calculation, contain all the outgoing radiation. The modes that eventually contain the outgoing radiation at long times are redshifted by such a huge amount by their long sojourn next to the event horizon, that they start off as modes with a wavelength much shorter than the Planck length. Since the laws of physics at such short distances are unknown, some find Hawking's original calculation unconvincing.[12][13][14][15]

The trans-Planckian problem is nowadays mostly considered a mathematical artifact of horizon calculations. The same effect occurs for regular matter falling onto a white hole solution. Matter which falls on the white hole accumulates on it, but has no future region into which it can go. Tracing the future of this matter, it is compressed onto the final singular endpoint of the white hole evolution, into a trans-Planckian region. The reason for these types of divergences is that modes which end at the horizon from the point of view of outside coordinates are singular in frequency there. The only way to determine what happens classically is to extend in some other coordinates that cross the horizon.

There exist alternative physical pictures which give the Hawking radiation in which the trans-Planckian problem is addressed. The key point is that similar trans-Planckian problems occur when the modes occupied with Unruh radiation are traced back in time.[16] In the Unruh effect, the magnitude of the temperature can be calculated from ordinary Minkowski field theory, and is not controversial.

Emission process

Hawking radiation is required by the Unruh effect and the equivalence principle applied to black hole horizons. Close to the event horizon of a black hole, a local observer must accelerate to keep from falling in. An accelerating observer sees a thermal bath of particles that pop out of the local acceleration horizon, turn around, and free-fall back in. The condition of local thermal equilibrium implies that the consistent extension of this local thermal bath has a finite temperature at infinity, which implies that some of these particles emitted by the horizon are not reabsorbed and become outgoing Hawking radiation.[16]

A Schwarzschild black hole has a metric:

The black hole is the background spacetime for a quantum field theory.

The field theory is defined by a local path integral, so if the boundary conditions at the horizon are determined, the state of the field outside will be specified. To find the appropriate boundary conditions, consider a stationary observer just outside the horizon at position

The local metric to lowest order is

which is Rindler in terms of τ = t/4M. The metric describes a frame that is accelerating to keep from falling into the black hole. The local acceleration, α = 1/ρ, diverges as ρ → 0.

The horizon is not a special boundary, and objects can fall in. So the local observer should feel accelerated in ordinary Minkowski space by the principle of equivalence. The near-horizon observer must see the field excited at a local temperature

this is the Unruh effect.

The gravitational redshift is given by the square root of the time component of the metric. So for the field theory state to consistently extend, there must be a thermal background everywhere with the local temperature redshift-matched to the near horizon temperature:

which can be simplified as:

The inverse temperature redshifted to r′ at infinity is

and r is the near-horizon position, near 2M, so this is really:

So a field theory defined on a black hole background is in a thermal state whose temperature at infinity is:

This can be expressed in a cleaner way in terms of the surface gravity of the black hole; this is the parameter that determines the acceleration of a near-horizon observer. In natural units (G = c = ħ = kB = 1), the temperature is

where κ is the surface gravity of the horizon. So a black hole can only be in equilibrium with a gas of radiation at a finite temperature. Since radiation incident on the black hole is absorbed, the black hole must emit an equal amount to maintain detailed balance. The black hole acts as a perfect blackbody radiating at this temperature.

In SI units, the radiation from a Schwarzschild black hole is blackbody radiation with temperature

where ħ is the reduced Planck constant, c is the speed of light, kB is the Boltzmann constant, G is the gravitational constant, M☉ is the solar mass, and M is the mass of the black hole.

From the black hole temperature, it is straightforward to calculate the black hole entropy. The change in entropy when a quantity of heat dQ is added is:

The heat energy that enters serves to increase the total mass, so:

The radius of a black hole is twice its mass in natural units, so the entropy of a black hole is proportional to its surface area:

Assuming that a small black hole has zero entropy, the integration constant is zero. Forming a black hole is the most efficient way to compress mass into a region, and this entropy is also a bound on the information content of any sphere in space time. The form of the result strongly suggests that the physical description of a gravitating theory can be somehow encoded onto a bounding surface.

Black hole evaporation

When particles escape, the black hole loses a small amount of its energy and therefore some of its mass (mass and energy are related by Einstein's equation E = mc2).

1976 Page numerical analysis

In 1976 Don Page calculated the power produced, and the time to evaporation, for a nonrotating, non-charged Schwarzschild black hole of mass M.[17] The calculations are complicated by the fact that a black hole, being of finite size, is not a perfect black body; the absorption cross section goes down in a complicated, spin-dependent manner as frequency decreases, especially when the wavelength becomes comparable to the size of the event horizon. Note that writing in 1976, Page erroneously postulates that neutrinos have no mass and that only two neutrino flavors exist, and therefore miscalculates the black hole lifetimes.

For a mass much larger than 1017 grams, Page deduces that electron emission can be ignored, and that black holes of mass M in grams evaporate via massless electron and muon neutrinos, photons, and gravitons in a time τ of

For a mass much smaller than 1017 g, but much larger than 5×1014 g, the emission of ultrarelativistic electrons and positrons will accelerate the evaporation, giving a lifetime of

A crude analytic estimate

The power emitted by a black hole in the form of Hawking radiation can easily be estimated for the simplest case of a nonrotating, non-charged Schwarzschild black hole of mass M. Combining the formulas for the Schwarzschild radius of the black hole, the Stefan–Boltzmann law of blackbody radiation, the above formula for the temperature of the radiation, and the formula for the surface area of a sphere (the black hole's event horizon), several equations can be derived:

Black hole surface gravity at the horizon:

Hawking radiation has a blackbody (Planck) spectrum with a temperature T given by:

Hawking radiation temperature:

The peak wavelength of this radiation is nearly 16 times the Schwarzschild radius of the black hole. Using Wien's displacement constant b = hc/4.9651 kB = 2.8978×10−3 m K:

Schwarzschild sphere surface area of Schwarzschild radius rs:

Stefan–Boltzmann power law:

For simplicity, assume a black hole is a perfect blackbody (ε = 1).

Stefan–Boltzmann–Schwarzschild–Hawking black hole radiation power law derivation:

Stefan–Boltzmann–Schwarzschild–Hawking power law:

where P is the energy outflow, ħ is the reduced Planck constant, c is the speed of light, and G is the gravitational constant. It is worth mentioning that the above formula has not yet been derived in the framework of semiclassical gravity.

The power in the Hawking radiation from a solar mass (M☉) black hole turns out to be a minuscule 9×10−29 W. It is indeed an extremely good approximation to call such an object 'black'.

Under the assumption of an otherwise empty universe, so that no matter, cosmic microwave background radiation, or other radiation falls into the black hole, it is possible to calculate how long it would take for the black hole to dissipate:

Given that the power of the Hawking radiation is the rate of evaporation energy loss of the black hole:

Since the total energy E of the black hole is related to its mass M by Einstein's mass–energy formula E = Mc2:

We can then equate this to our above expression for the power:

This differential equation is separable, and we can write:

The black hole's mass is now a function M(t) of time t. Integrating over M from M0 (the initial mass of the black hole) to zero (complete evaporation), and over t from zero to tev:

The evaporation time of a black hole is proportional to the cube of its mass:

The time that the black hole takes to dissipate is:

where M0 is the mass of the black hole.

The lower classical quantum limit for mass for this equation is equivalent to the Planck mass, mP.

Hawking radiation evaporation time for a Planck mass quantum black hole:

where tP is the Planck time.

For a black hole of one solar mass (M☉ = 1.98892×1030 kg), we get an evaporation time of 2.098×1067 years—much longer than the current age of the universe at (13.799±0.021)×109 years.[18]

But for a black hole of 1011 kg, the evaporation time is 2.667 billion years. This is why some astronomers are searching for signs of exploding primordial black holes.

However, since the universe contains the cosmic microwave background radiation, in order for the black hole to dissipate, it must have a temperature greater than that of the present-day blackbody radiation of the universe of 2.7 K = 2.3×10−4 eV. This implies that M must be less than 0.8% of the mass of the Earth[19] – approximately the mass of the Moon.

Cosmic microwave background radiation universe temperature:

Hawking total black hole mass:

where M⊕ is the total Earth mass.

In common units,

So, for instance, a 1-second-life black hole has a mass of 2.28×105 kg, equivalent to an energy of 2.05×1022 J that could be released by 5×106 megatons of TNT. The initial power is 6.84×1021 W.

Black hole evaporation has several significant consequences:

- Black hole evaporation produces a more consistent view of black hole thermodynamics by showing how black holes interact thermally with the rest of the universe.

- Unlike most objects, a black hole's temperature increases as it radiates away mass. The rate of temperature increase is exponential, with the most likely endpoint being the dissolution of the black hole in a violent burst of gamma rays. A complete description of this dissolution requires a model of quantum gravity, however, as it occurs when the black hole approaches Planck mass and Planck radius.

- The simplest models of black hole evaporation lead to the black hole information paradox. The information content of a black hole appears to be lost when it dissipates, as under these models the Hawking radiation is random (it has no relation to the original information). A number of solutions to this problem have been proposed, including suggestions that Hawking radiation is perturbed to contain the missing information, that the Hawking evaporation leaves some form of remnant particle containing the missing information, and that information is allowed to be lost under these conditions.

Large extra dimensions

The formulae from the previous section are only applicable if the laws of gravity are approximately valid all the way down to the Planck scale. In particular, for black holes with masses below the Planck mass (~10−8 kg), they result in impossible lifetimes below the Planck time (~10−43 s). This is normally seen as an indication that the Planck mass is the lower limit on the mass of a black hole.

In a model with large extra dimensions, the values of Planck constants can be radically different, and the formulae for Hawking radiation have to be modified as well. In particular, the lifetime of a micro black hole with a radius below the scale of the extra dimensions is given by equation 9 in Cheung (2002)[20] and equations 25 and 26 in Carr (2005).[21]

where M∗ is the low energy scale, which could be as low as a few TeV, and n is the number of large extra dimensions. This formula is now consistent with black holes as light as a few TeV, with lifetimes on the order of the "new Planck time" ~10−26 s.

Hawking radiation in loop quantum gravity

A detailed study of the quantum geometry of a black hole horizon has been made using loop quantum gravity.[22] Loop-quantization reproduces the result for black hole entropy originally discovered by Bekenstein and Hawking. Further, it led to the computation of quantum gravity corrections to the entropy and radiation of black holes.

Based on the fluctuations of the horizon area, a quantum black hole exhibits deviations from the Hawking spectrum that would be observable were X-rays from Hawking radiation of evaporating primordial black holes to be observed.[23] The quantum effects are centered at a set of discrete and unblended frequencies highly pronounced on top of Hawking radiation spectrum.[24]

Experimental observation of Hawking radiation

Under experimentally achievable conditions for gravitational systems this effect is too small to be observed directly. In September 2010, however, an experimental set-up created a laboratory "white hole event horizon" that the experimenters claimed was shown to radiate Hawking radiation,[25] although its status as a genuine confirmation remains in doubt.[26] Some scientists predict that Hawking radiation could be studied by analogy using sonic black holes, in which sound perturbations are analogous to light in a gravitational black hole and the flow of an approximately perfect fluid is analogous to gravity.[27] [28]

See also

References

- ↑ Rose, Charlie. "A conversation with Dr. Stephen Hawking & Lucy Hawking". charlierose.com. Archived from the original on March 29, 2013.

- ↑ Levi Julian, Hana (3 September 2012). "'40 Years of Black Hole Thermodynamics' in Jerusalem". Arutz Sheva. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- ↑ Hawking, Stephen (1988). A Brief History of Time. Bantam Books. ISBN 0-553-38016-8.

- ↑ Giddings, S.; Thomas, S. (2002). "High energy colliders as black hole factories: The end of short distance physics". Physical Review D. 65 (5): 056010. arXiv:hep-ph/0106219

. Bibcode:2002PhRvD..65e6010G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.65.056010.

. Bibcode:2002PhRvD..65e6010G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.65.056010. - ↑ Dimopoulos, S.; Landsberg, G. (2001). "Black Holes at the Large Hadron Collider". Physical Review Letters. 87 (16): 161602. arXiv:hep-ph/0106295

. Bibcode:2001PhRvL..87p1602D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.87.161602. PMID 11690198.

. Bibcode:2001PhRvL..87p1602D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.87.161602. PMID 11690198. - ↑ "The case for mini black holes". CERN courier. November 2004.

- ↑ Henderson, Mark (September 9, 2008). "Stephen Hawkings 50 bet on the world the universe and the God particle". The Times. London. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- ↑ Belgiorno, F.; Cacciatori, S. L.; Clerici, M.; Gorini, V.; Ortenzi, G.; Rizzi, L.; Rubino, E.; Sala, V. G.; Faccio, D. (2010). "Hawking radiation from ultrashort laser pulse filaments". Phys. Rev. Lett. 105: 203901. arXiv:1009.4634

. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.203901.

. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.203901. - ↑ Grossman, Lisa (September 29, 2010). "Ultrafast Laser Pulse Makes Desktop Black Hole Glow". Wired. Retrieved April 30, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Kumar, K. N. P.; Kiranagi, B. S.; Bagewadi, C. S. (2012). "Hawking Radiation – An Augmentation Attrition Model". Adv. Nat. Sci. 5 (2): 14–33. doi:10.3968/j.ans.1715787020120502.1817.

- ↑ Carroll, Bradley; Ostlie, Dale (1996). An Introduction to Modern Astrophysics. Addison Wesley. p. 673. ISBN 0-201-54730-9.

- ↑ Helfer, A. D. (2003). "Do black holes radiate?". Reports on Progress in Physics. 66 (6): 943–1008. arXiv:gr-qc/0304042

. Bibcode:2003RPPh...66..943H. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/66/6/202.

. Bibcode:2003RPPh...66..943H. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/66/6/202. - ↑ 't Hooft, G. (1985). "On the quantum structure of a black hole". Nuclear Physics B. 256: 727–745. Bibcode:1985NuPhB.256..727T. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(85)90418-3.

- ↑ Jacobson, T. (1991). "Black-hole evaporation and ultrashort distances". Physical Review D. 44 (6): 1731–1739. Bibcode:1991PhRvD..44.1731J. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.44.1731.

- ↑ Brout, R.; Massar, S.; Parentani, R.; Spindel, P. (1995). "Hawking radiation without trans-Planckian frequencies". Physical Review D. 52 (8): 4559–4568. arXiv:hep-th/9506121

. Bibcode:1995PhRvD..52.4559B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.52.4559.

. Bibcode:1995PhRvD..52.4559B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.52.4559. - 1 2 For an alternative derivation and more detailed discussion of Hawking radiation as a form of Unruh radiation see de Witt, Bruce (1980). "Quantum gravity: the new synthesis". In Hawking, S.; Israel, W. General Relativity: An Einstein Centenary. p. 696. ISBN 0-521-29928-4.

- ↑ Page, Don N. (1976). "Particle emission rates from a black hole: Massless particles from an uncharged, nonrotating hole". Physical Review D. 13 (2): 198–206. Bibcode:1976PhRvD..13..198P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.13.198.

- ↑ Planck Collaboration (2016). "Planck 2015 results. XIII. Cosmological parameters". Astron. Astrophys. 594: art. A13 (see Table 4, p. 31). arXiv:1502.01589

. Bibcode:2015arXiv150201589P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201525830.

. Bibcode:2015arXiv150201589P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201525830. - ↑ Kapusta, Joseph (1999). "The Last Eight Minutes of a Primordial Black Hole". arXiv:astro-ph/9911309

.

. - ↑ Cheung, Kingman (2002). "Black Hole Production and Large Extra Dimensions". Phys. Rev. Lett. 88: 221602. arXiv:hep-ph/0110163

. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.221602.

. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.221602. - ↑ Carr, B. J. (2005). "Primordial Black Holes – Recent Developments". 22nd Texas Symposium at Stanford, 12–17 December 2004. arXiv:astro-ph/0504034

.

. - ↑ Ashtekar, A.; Baez, J.; Corichi, A.; Krasnov, K. "Quantum Geometry and Black Hole Entropy". Phys. Rev. Lett. 80: 904–907. arXiv:gr-qc/9710007

. Bibcode:1998PhRvL..80..904A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.80.904.

. Bibcode:1998PhRvL..80..904A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.80.904. - ↑ Ansari, M. H. "Spectroscopy of a canonically quantized horizon". Nucl. Phys. B. 783: 179–212. arXiv:hep-th/0607081

. Bibcode:2007NuPhB.783..179A. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysb.2007.01.009.

. Bibcode:2007NuPhB.783..179A. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysb.2007.01.009. - ↑ Ansari, M. H. "Generic degeneracy and entropy in loop quantum gravity". Nucl. Phys. B. 795: 635–644. arXiv:gr-qc/0603121

. Bibcode:2008NuPhB.795..635A. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysb.2007.11.038.

. Bibcode:2008NuPhB.795..635A. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysb.2007.11.038. - ↑ "First Observation of Hawking Radiation". MIT Technology Review. MIT. September 27, 2010.

- ↑ Matson, John (October 1, 2010). "Artificial event horizon emits laboratory analog to theoretical black hole radiation". Scientific American.

- ↑ Barceló, C.; Liberati, S.; Visser, M. (2003). "Towards the observation of Hawking radiation in Bose–Einstein condensates". Int. J. Mod. Phys. A. 18: 3735–3745. arXiv:gr-qc/0110036

. Bibcode:2003IJMPA..18.3735B. doi:10.1142/s0217751x0301615x.

. Bibcode:2003IJMPA..18.3735B. doi:10.1142/s0217751x0301615x. - ↑ Steinhauer, J. (2016). "Observation of quantum Hawking radiation and its entanglement in an analogue black hole". Nature Phys. 12: 959–965. doi:10.1038/nphys3863.

Further reading

- Hawking, S. W. (1974). "Black hole explosions?". Nature. 248 (5443): 30–31. Bibcode:1974Natur.248...30H. doi:10.1038/248030a0. → Hawking's first article on the topic

- Page, Don N. (1976). "Particle emission rates from a black hole: Massless particles from an uncharged, nonrotating hole". Phys. Rev. D. 13 (2): 198–206. Bibcode:1976PhRvD..13..198P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.13.198. → first detailed studies of the evaporation mechanism

- Carr, B. J.; Hawking, S. W. (1974). "Black holes in the early universe". Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 168 (2): 399–415. Bibcode:1974MNRAS.168..399C. doi:10.1093/mnras/168.2.399. → links between primordial black holes and the early universe

- Barrau, A.; et al. (2002). "Antiprotons from primordial black holes". Astron. Astrophys. 388 (2): 676–687. arXiv:astro-ph/0112486

. Bibcode:2002A&A...388..676B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20020313.

. Bibcode:2002A&A...388..676B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20020313. - Barrau, A.; et al. (2003). "Antideuterons as a probe of primordial black holes". Astron. Astrophys. 398 (2): 403–410. arXiv:astro-ph/0207395

. Bibcode:2003A&A...398..403B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20021588.

. Bibcode:2003A&A...398..403B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20021588. - Barrau, A.; Féron, C.; Grain, J. (2005). "Astrophysical Production of Microscopic Black Holes in a Low–Planck-Scale World". J. Am. Astronom. Soc. 630 (2): 1015–1019. arXiv:astro-ph/0505436

. Bibcode:2005ApJ...630.1015B. doi:10.1086/432033. → experimental searches for primordial black holes thanks to the emitted antimatter

. Bibcode:2005ApJ...630.1015B. doi:10.1086/432033. → experimental searches for primordial black holes thanks to the emitted antimatter - Barrau, A.; Boudoul, G. "Some aspects of primordial black hole physics". arXiv:astro-ph/0212225

. → cosmology with primordial black holes

. → cosmology with primordial black holes - Barrau, A.; Grain, J.; Alexeyev, S. O. (2004). "Gauss–Bonnet black holes at the LHC: beyond the dimensionality of space". Phys. Lett. B. 584 (1–2): 114–122. arXiv:hep-ph/0311238

. Bibcode:2004PhLB..584..114B. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2004.01.019. → searches for new physics (quantum gravity) with primordial black holes

. Bibcode:2004PhLB..584..114B. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2004.01.019. → searches for new physics (quantum gravity) with primordial black holes - Kanti, Panagiota (2004). "Black Holes in Theories with Large Extra Dimensions: a Review". Int. J. Mod. Phys. A. 19 (29): 4899–4951. arXiv:hep-ph/0402168

. Bibcode:2004IJMPA..19.4899K. doi:10.1142/S0217751X04018324. → evaporating black holes and extra-dimensions

. Bibcode:2004IJMPA..19.4899K. doi:10.1142/S0217751X04018324. → evaporating black holes and extra-dimensions - Ida, Daisuke; Oda, Kin'ya; Park, Seong-chan (2003). "Rotating black holes at future colliders: Greybody factors for brane fields". Phys. Rev. D. 67: 064025. arXiv:hep-th/0212108

. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.67.064025.

. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.67.064025. - Ida, Daisuke; Oda, Kin'ya; Park, Seong-chan (2005). "Rotating black holes at future colliders. II. Anisotropic scalar field emission". Phys. Rev. D. 71: 124039. arXiv:hep-th/0503052

. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.71.124039.

. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.71.124039. - Ida, Daisuke; Oda, Kin'ya; Park, Seong-chan (2006). "Rotating Black Holes at Future Colliders. III. Determination of Black Hole Evolution". Phys. Rev. D. 73: 124022. arXiv:hep-th/0602188

. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.73.124022. → determination of black hole's life and extra dimensions

. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.73.124022. → determination of black hole's life and extra dimensions - Nicolaevici, Nistor (2003). "Blackbody spectrum from accelerated mirrors with asymptotically inertial trajectories". J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 36 (27): 7667–7677. doi:10.1088/0305-4470/36/27/317. → consistent derivation of the Hawking radiation in the Fulling–Davies mirror model.

- Smolin, L. (November 2006). "Quantum gravity faces reality" (PDF). Physics Today. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 10, 2008. consists of the recent developments and predictions of loop quantum gravity about gravity in small scales including the deviation from Hawking radiation effect by Ansari.

- Ansari, Mohammad H. (2007). "Spectroscopy of a canonically quantized horizon". Nucl. Phys. B. 783: 179–212. arXiv:hep-th/0607081

. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysb.2007.01.009. → studies the deviation of a loop quantized black hole from Hawking radiation. A novel observable quantum effect of black hole quantization is introduced.

. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysb.2007.01.009. → studies the deviation of a loop quantized black hole from Hawking radiation. A novel observable quantum effect of black hole quantization is introduced. - Shapiro, Stuart L.; Teukolsky, Saul A. (1983). Black Holes, White Dwarfs, and Neutron Stars: The Physics of Compact Objects. Wiley-Interscience. p. 366. ISBN 978-0-471-87316-7. → Hawking radiation evaporation formula derivation.

- Leonhardt, Ulf; Maia, Clovis; Schuetzhold, Ralf (2010). "Focus on Classical and Quantum Analogs for Gravitational Phenomena and Related Effects". New J. Phys. 14: 105032. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/14/10/105032.

External links

- Hawking radiation calculator tool

- The case for mini black holes A. Barrau & J. Grain explain how the Hawking radiation could be detected at colliders

- Black Holes – Anybody out there?

- University of Colorado at Boulder

- Hawking radiation on arxiv.org

- Hawking radiation observed in laboratory?