Hatzegopteryx

| Hatzegopteryx Temporal range: Late Cretaceous, 66 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| A, left humerus in ventral view; B, distal view | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | †Pterosauria |

| Suborder: | †Pterodactyloidea |

| Family: | †Azhdarchidae |

| Genus: | †Hatzegopteryx Buffetaut, Grigorescu & Csiki, 2002 |

| Species: | †Hatzegopteryx thambema Buffetaut, Grigorescu & Csiki, 2002 |

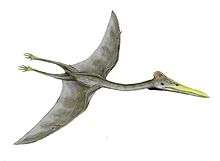

Hatzegopteryx ("Hațeg basin wing") is a genus of azhdarchid pterosaur, known from incomplete remains found in Hunedoara County, Transylvania, Romania. The skull fragments, left humerus, and other fossilized remains indicate it was among the largest pterosaurs. The skeleton of Hatzegopteryx has been considered identical to the known remains of Quetzalcoatlus northropi. Q. northropi has not yet been properly described, and if it is not a nomen dubium, Hatzegopteryx is possibly its junior synonym.[1] However, as issues on Quetzalcoatlus own lack of diagnosis continue, such assessments cannot be made.[2]

Description

Skull

Hatzegopteryx apparently had a robust skull broadened in the rear, and a massive jaw. Its lower jaw featured a unique groove in its point of articulation, also seen in some other pterosaurs, that would have allowed the animal to achieve a very wide gape. Many of the fossilized bones of Hatzegopteryx resemble those of the closely related Quetzalcoatlus sp., though in Hatzegopteryx the skull was much more heavily built, and had a markedly different jaw articulation, similar to that seen in Pteranodon. Based on comparisons with other pterosaurs, Nyctosaurus and Anhanguera, Buffetaut and colleagues when initially describing the specimens estimated that the skull of Hatzegopteryx was probably almost 3 m (9.8 ft) in length, which would have made it larger than that of the largest Quetzalcoatlus species and among the largest skulls of any known non-marine animals.[3]

The skull of Hatzegopteryx was also unique in its heavy, robust construction. Most pterosaur skulls are made up of very lightweight plates and struts. In Hatzegopteryx, the skull bones are stout and robust, with large-ridged muscle insertion areas. In their 2002 description, Buffetaut and colleagues suggested that in order to fly, the skull weight of this pterosaur must have been reduced in some unconventional way (while they allowed that it could have been flightless, they found this unlikely due to the similarity of its wing bones to flying pterosaurs). The authors theorized that the necessary weight reduction was accomplished by the internal structure of the skull bones, which were full of small pits and hollows (alveoli) up to 10 mm long, separated by a matrix of incredibly thin bony struts (trabeculae), a feature also found in some parts of Hatzegopteryx wing bones. The authors pointed out that this unusual construction, which differed significantly from the irregular internal structure of other pterosaur skulls, resembles the structure of expanded polystyrene, the substance used to make Styrofoam. They noted that this would allow a sturdy, stress-resistant construction while remaining lightweight, and would have allowed the huge-headed animal to fly.[3]

Recent studies on Hatzegopteryx showcase that it had a proportionally short, deep beak, grouping with the "blunt-beaked" azhdarchids.[4] This contrasts with at least the smaller Quetzalcoatlus species, which groups with the "slender-beaked" forms, having long, slender jaws.[5]

Vertebrae

Recent studies on Hatzegopteryx's neck vertebrae show them to be considerably robust and short compared to those of other azhdarchids, suggesting a less elongated but more muscular neck.[6]

Size

The authors estimated the size of Hatzegopteryx by comparing the humerus fragment, 236 mm (9.3 in) long, with that of Quetzalcoatlus, of which specimen TMM 41450-3 has a 544 mm (1 ft 9.4 in) long humerus. Observing that the Hatzegopteryx fragment presented less than half of the original bone, they established that it could possibly have been "slightly longer" than that of Quetzalcoatlus. They noted that the wing span of the latter had in 1981 been estimated at 11 to 12 metres (36–39 ft), while earlier estimates had strongly exceeded this at 15 to 20 metres (49-65.6 ft). From this they concluded that an estimate of a 12-metre (39 ft) wing span for Hatzegopteryx was conservative "if its humerus was indeed somewhat longer than that of Q. northropi".[3] In 2003 they moderated the estimates to a close to 12 metres (39 ft) wing span and an over 2.5 m (8.2 ft) skull length.[7] In 2010 Mark Witton e.a. stated that any appearance that the Hatzegopteryx humerus was bigger than TMM 41450-3 had been caused by a distortion of the bone after deposition and that the species thus likely had no larger wingspan than Quetzalcoatlus, today generally estimated at 10 to 11 metres (32.8–36 ft).[8]

Discovery

The genus was named in 2002 by French paleontologist Eric Buffetaut, and Romanian paleontologists Dan Grigorescu and Zoltan Csiki. It is known from only the type species, Hatzegopteryx thambema. The generic name is derived from the Hatzeg (or Hațeg) basin of Transylvania, the so-called Hațeg Island, where the bones were found, and from Greek pteryx, or 'wing'. The specific name thambema is derived from the Greek for 'monster', in reference to its huge size.[3]

Hatzegopteryx hails from the upper part of the Middle Densuș Ciula Formation of Vălioara, northwestern Hațeg Basin, Transylvania, western Romania, which has been dated to the late Maastrichtian stage of the late Cretaceous Period, around 66 million years ago.[9]

The holotype, FGGUB R 1083A, consists of the back part of the skull and the damaged proximal part of a left humerus.[3] A 38.5 centimeter long middle section of a femur found nearby, FGGUB R1625, may also have belonged to Hatzegopteryx.[7] FGGUB R1625 belonged to an individual with a five to six metres wingspan. The later reported fragments represent medium-sized animals.[10]

In 2011, additional finds were reported: the front of a mandibula, the possibly third phalanx of the wing finger, an unfused scapulocoracoid, a scapula, cervical vertebrae and a piece of a humerus.[11] These remains were named Eurazhdarcho in 2013.[10]

Paleobiology

Like all azhdarchid pterosaurs, Hatzegopteryx was a terrestrial predator. Due to its large size in an environment otherwise dominated by island dwarf dinosaurs, with no large theropod in the region, it has at times been implicated to be an apex predator. This assertion may be supported by studies on its neck and jaws, which are more robust than those of other azhdarchids and may imply a speciation towards comparatively larger prey.[12] Another pterosaur, Thalassodromeus, is similarly suggested to be "raptorial".[13]

See also

References

- ↑ Witton, M.P., Martill, D.M. and Loveridge, R.F. (2010). "Clipping the Wings of Giant Pterosaurs: Comments on Wingspan Estimations and Diversity." Acta Geoscientica Sinica, 31 Supp.1: 79-81

- ↑ Quetzalcoatlus: the media concept vs the science

- 1 2 3 4 5 Buffetaut, E., Grigorescu, D., and Csiki, Z. (2002). "A new giant pterosaur with a robust skull from the latest Cretaceous of Romania." Naturwissenschaften, 89(4): 180-184. Abstract

- ↑ Witton, Mark et al (2013). "Pterosaur overlords of Transylvania: short-necked giant azhdarchids in Late Cretaceous Romania". The Annual Symposium of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Comparative Anatomy

- ↑ Witton, M. P. (2013). Pterosaurs: Natural History, Evolution, Anatomy. Princeton University Press.

- ↑ Witton, Mark et al (2013). "Pterosaur overlords of Transylvania: short-necked giant azhdarchids in Late Cretaceous Romania". The Annual Symposium of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Comparative Anatomy

- 1 2 Buffetaut, E., Grigorescu, D. and Csiki, Z. (2003). "Giant azhdarchid pterosaurs from the terminal Cretaceous of Transylvania (western Romania)", Geological Society, London, Special Publications 217: 91-104

- ↑ Witton, M.P. and Habib, M.B. (2010). "On the Size and Flight Diversity of Giant Pterosaurs, the Use of Birds as Pterosaur Analogues and Comments on Pterosaur Flightlessness." PLoS ONE, 5(11): e13982.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013982

- ↑ "Hatzegopteryx thambema". Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- 1 2 Vremir, M., Kellner, A.W.A., Naish, D., Dyke, G.J., 2013, "A New Azhdarchid Pterosaur from the Late Cretaceous of the Transylvanian Basin, Romania: Implications for Azhdarchid Diversity and Distribution", PLoS ONE 8(1): e54268. doi:10.1371

- ↑ Vremir, M., Dyke, G., Csiki, Z., 2011, "Late Cretaceous pterosaurian diversity in the Transylvanian and Hateg basins (Romania): new results", The 8th Romanian Symposium on Palaeontology, Bucharest. Abstract vol: 131–132

- ↑ Witton, Mark et al (2013). "Pterosaur overlords of Transylvania: short-necked giant azhdarchids in Late Cretaceous Romania". The Annual Symposium of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Comparative Anatomy

- ↑ Witton, M. P. (2013). Pterosaurs: Natural History, Evolution, Anatomy. Princeton University Press.