Telli Hasan Pasha

| Hasan Predojević | |

|---|---|

| Native name | Hasan Predojević |

| Birth name | Nikola Predojević |

| Born |

c. 1530 either Lušci Palanka, Sanjak of Bosnia; or Bijela Rudina, Sanjak of Herzegovina, Ottoman Empire |

| Died |

22 June 1593 (aged 63) Sisak, Kingdom of Croatia, Habsburg Monarchy |

| Allegiance |

|

| Years of service | –1593 |

| Rank | Beylerbey of Bosnia Eyalet, Vizier |

| Battles/wars |

|

Hasan Predojević (c. 1530 – 22 June 1593), known in Ottoman Turkish as Telli Hasan Pasha (Turkish: Telli Hasan Paşa)[a], was the fifth Ottoman beylerbey (vali) of Bosnia and a notable Ottoman Bosnian military commander, who led an invasion of the Habsburg Kingdom of Croatia during the Ottoman wars in Europe.

Early life

He was born Nikola Predojević[1][2] into the Predojević clan, Orthodox Vlachs[3][4] from Eastern Herzegovina. According to Muvekkit Hadžihuseinović he was born in Lušci Palanka, in the Bosanska Krajina region,[5] however, according to his nickname Hersekli, he was from Herzegovina.[6] The birthplace has been given specifically as Bijela Rudina, Bileća.[7]

An Ottoman sultan wrote in a book that he had requested from a notable lord in Herzegovina, named Predojević, that 30 small Serb[b] children (including Predojević's only son Jovan, and his nephew Nikola) to be sent to Ottoman service (see devshirme).[8] The very young Nikola was then taken to Constantinople as acem-i oğlan (foreign child) and brought up in the Sultan's court, converting to Islam, adopting the name Hasan and advancing to the post of çakircibaşa (chief falconer and commander of falconers in the Sultan's court).[9]

After having been appointed Beglerbeg of Bosnia, Telli Hasan Pasha had the Rmanj Monastery renewed as a seat of his brother, Orthodox monk Gavrilo Predojević.[10] He also founded a mosque in Polje, Grabovica, in the Bileća municipality.[9]

Ottoman service

Sanjak-bey of Segedin

During the rule of Murat III (1574–1595) he became Sanjak-bey of the Sanjak of Segedin,[11] where he stayed until June 1591.[9]

Beylerbey of Bosnia

He was elevated and appointed Beglerbeg (Governor-General) of the Bosnia Eyalet in 1591. A bellicose and dynamic military leader,[12] Hasan strengthened the army of the Eyalet equipping it with better horses and erecting a bridge at Gradiška with the purpose of easier maneuvering between Bosnia and Slavonia.[13]

.jpg)

In August 1591, without a declaration of war, Hasan Pasha attacked Habsburg Croatia and reached Sisak, but was repelled after 4 days of fighting. Thomas Erdődy, the Ban of Croatia, launched a counterattack and seized much of the Moslavina region. The same year Hasan Pasha launched another attack, taking the town of Ripač on the Una River. These raids forced the Ban to declare a general uprising to defend the country in late January, 1592.[14] These actions of the Ottoman regional forces under Hasan Pasha seem to have been contrary to the interest and policy of the central Ottoman administration in Constantinople,[15] and due rather to aims of conquest and organized plundering by the war-like Bosnian sipahi, although perhaps also under the pretext of putting an end to Uskok (Balkan Habsburg-sided pirates and bandits engaged in guerrilla warfare against the Ottomans) raids into the Eyalet; since the two realms had signed a nine-year peace treaty earlier in 1590. Hasan Pasha's forces of approximately 20,000 janissaries[16] continued to raid the region, with the goal of seizing the strategically important town of Senj and its port, and to eliminate the Uskoci as well; because of all this, the Holy Roman Emperor sent his ambassador so he would beg that Hasan Pasha be removed from his post, or otherwise an end would be put to the existing truce. The ambassador was told in reply, that it belonged to the Grand Vizier and to Derviš-paša, the Sultan's favourite, to repel their aggressions against the Ottoman Empire; that, the imperial ambassador was told, was a sufficient answer.[17] After learning this, Hasan Pasha felt himself encouraged enough to lead his forces towards Bihać,[18] which was conquered on June 19, 1592[19] after eight days of siege,[20] along with several surrounding forts.[9] Records show that nearly 2,000 people died in defense of the town, and an estimated 800 children were taken for Ottoman servitude (see devshirme), to be educated in Islam and become janissaries, as Hasan had been himself. After having placed a sufficient garrison in Bihać, he erected two other fortresses in its vicinity; the command of which he conferred to Rustem-beg, who was the leader of the Grand Vizier Ferhad Pasha's militia.[21] In all, during this two-year campaign, the Ottoman Bosnian regional invading forces, led by Hasan Pasha, burned to the ground 26 cities throughout the Croatian Frontier and took some 35,000 war captives.[22][23] At the same time, at Predojević's order, Orthodox Serbs were settled in the "whole region around Bihać" from 1592 to 1593,[24] while Orthodox Vlachs from Eastern Herzegovina, and with them some Turkish and Bosnian Muslim aristocratic feudal landlords as well,[c] were settled in the central part of the Una river region (Pounje), around Brekovica, Ripač, Ostrovica and Vrla Draga up to Sokolovac, in such numbers that they formed a significant population of this region.[25][26][27]

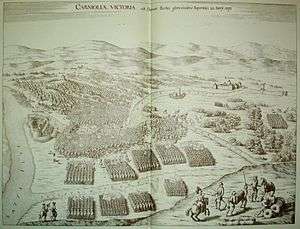

At first, Telli Hasan Pasha's troops met little resistance, allowing them to capture numerous Uskoci settlements, where they enslaved or slaughtered the entire population and burned the settlements. His forces soon besieged and captured Senj and exterminated the Uskoci population. For his successes, the Pasha was awarded the title of "Vizier" by the Sultan. However, the following year, Telli Hasan Pasha decided to advance further into Croatia. His force of some twenty-thousand was soundly defeated in his third attempt to conquer Sisak, in the battle that took place near by that fortified town,[28] in which Hasan Pasha is generally reported to have died,[29][30] alongside his brother Džafer Bey (governor of the Sanjak of Pakrac-Cernica), Mehmed Pasha (the sultan's nephew and governor of the Sanjak of Herzegovina), Opardi Bey (governor of the Sanjak of Klis-Livno),[31][32] and many other Turkish and Bosnian Muslim Pashas, Beys and Aghas,[33] who accompanied the Vizier in his campaign, having been routed. According to Mustafa Naima: "The brave Hasan Pasha himself also met with his fate, having fallen into the river with one of the bridges which had been cut to prevent the pursuit of the enemy. Such was the result of this terrible day."[34] Indeed, after he had drowned in the river, his dress was taken as a trophy to Ljubljana where it was remade into the sacerdotal coat worn by the bishop during the celebration of the Thanksgiving mass.[35]

Aftermath and legacy

A monastery was built on the location of his grave, after requests of a Predojević to Sultan Murad, who also granted Kolunić and Smiljan (metochion).[2] Safvet-beg Bašagić praises him as a meritorious general and statesman, as well as a great and fearless hero.[9]

Annotations

- ^ His birth name was Nikola Predojević.[2] Chroniclers and historians call him by various names, such as (in Serbo-Croatian): "Gazi Hasan-paša", "Hasan-paša Došen" (this is the name Evliya Çelebi calls him by),[9] "Predojević", "Klobučarić", "Hersekli", "Deli Hasan-paša" and "Derviš Hasan-paša".[36]

- ^ In Serb historiography the Vlach ethnonym is usually claimed to be a synonym of Serbs during this period.[37] But historians such as Tihomir Đorđević point to the already known fact that the name Vlach didn't only refer to genuine Vlachs or Serbs, but also to cattle breeders in general.[37] Vlach (Ottoman Turkish: Eflak) was a social class within the Millet system in the Ottoman Empire, with considerable socio-economical privileges, even in military matters (they were allowed, for example, as they served regularly as Ottoman Auxiliary troops, to bear arms and to ride horses; privileges that were denied to all other Zimmîs by the Šerijat or Islamic Law),[38] compared to the class of the Reaya (see the Vlach (social class) article for further information).[39] Croatian nationalist historians, such as friar Dominik Mandić in his Hrvati i Srbi: dva stara, razlicita naroda ("Croats and Serbs: two old and different nations"), ignored this and proclaimed all >>Vlachs<< as a separate Aromanian nation, with the suggestion that in Bosnia as supposedly Croatian land there were no Serbs, but these were all Aromanians.

- ^ As it is reported in the Turali-beg's Vakufname of 1562, some great Turkish and Bosnian Muslim landholding military nobles (Sipahi and Timarli) brought with them Orthodox Vlach population from the Sandžak of Smederevo into Bosnia, in order that they farmed their lands.[40][41] The Turks often profited greatly from Vlach experience in carrying goods and the skill and speed with which they crossed the mountain regions. For that very reason, aside of serving as auxiliary soldiers in the Ottoman military (see Martolos and Vlach), they always accompanied the Ottoman armies in their expeditions throughout the Balkans, up to the North-West, in whole communities; being intended for populating the newly conquered territories as border military colonies, called katun or džemaat (which were composed of about 20 to 50 houses); at the head of which there was a katunar or primikur ("headman"). In addition, these Vlachs often served the advancing Ottoman forces by spying in enemy Christian territory. In exchange for their regular duties in the military and in guarding the borders; Ottoman authorities granted them by law certain rights, such as that of being largely exempted of paying any tax but only that of an annual rent of one gold 'ducat' or 'florin' to pay by each one of their households, hence coming to be called as "Florin" or "Ducat Vlachs" (Ottoman Turkish: Filurîci Eflakân).[42] Therefore, it can be similarly concluded that, this time, as Hasan Predojević's armies were advancing throughout the Croatian Frontier, the Spahije who were participating in the Beglerbeg's campaigns in Habsburg Croatia; were, at the same time, to establish themselves as landowning lords in those newly conquered regions, while, at the same time, taking advantage of the Vlach-Serb manpower to work their newly acquired estates.

References

- ↑ Гласник 3. М. 9, 1897, 695, упор. и Б. Вила 19, 1904, 71. — 25.

»Никола Предојевић« је и име пастира (доцније Хасан паше) који је освојио Бихаћ. Он је пасао овце на »Предојевића Главици«

- 1 2 3 Bosanska vila, Vol. 19. Nikola T. Kašiković. 1904. p. 71.

Предојевић ... Никола [...] Цар турски, Мурат П. допусти Предојевићу да цркву саградити може, а царица (султанија) му пак даде све трошкове, што су за градњу требали. Предојевић на гробници убијеног Николе сагради манастир, те по томе и манастир ...

- ↑ Kurtović, Esad (2011). Iz historije vlaha Predojevića [About the history of Predojević Vlachs]. Godišnjak (in Bosnian). Academy of Sciences and Arts of Bosnia and Herzegovina. ISSN 2232-7770.

- ↑ Dominik Mandić (1990). Hrvati i Srbi: dva stara, razlicita naroda. Nakladni zavod Matice Hrvatske. p. 201. ISBN 978-86-401-0081-6.

[After the fall of Bihać in 1592 the Bosnian Beylerbey Hasan Pasha Predojević settled Orthodox Vlachs from Eastern Herzegovina, especially those of his own Predojević clan, in the central part of Pounje around Brekovica, Ripač, Ostrovica and Vrla Draga up to Sokolovac.]

- ↑ Mithad Kozličić (2003). Unsko-sansko područje na starim geografskim kartama. Nacionalna i Univerzitetska Biblioteka Bosne i Hercegovine. ISBN 978-9958-500-22-0.

To je doista Hasan-paša Predojević. Prema HADŽIHUSEINOVIĆ MUVEKKIT, S. S., 1999, svezak l, str. 183, Hasan- paša je islamizirani Bosanac iz "sela Lušci, u kadiluku Mejdan", tj. iz današnjeg naselja Lušci- Palanka pored Starog Majdana ...

- ↑ Srpski etnografski zbornik. 12. 1909. p. 119.

Predoeuich Vlachus comitis Pauli", који је на двадест и пет коња изгонио со из Дубравника.") Осим тога зна се, да је био и један паша који се звао Херцегли Гази Хасан паша Предојевић, за кога неки тврде, да је поријеклом нз Б. Крајине, али из самог атрибута Херцегли види се да је из Херцеговине, као што је то и Башагић тачно опазио ...

- ↑ Književnost. 1991.

Ријеч је о предању да је израду ове фреске платио Хасан-паша Предојевић, поријеклом с Бијеле Рудине, који је у Планој код Би- леће саградио џамију с четвртастим минаретом, а у Пријевору је за мајку саградио цркву која на ...

- ↑ "Предојевић кнез и његов братић Никола". Srpski etnografski zbornik, Vol. 41. Državna štamparija. 1927. p. 392.

У старо вријеме писао је цар турски књигу у Херцеговину некаквом знатном кнезу, званом Предо- јевићу, да му пошаље тридесет малијех српскијех дјечака, и с њима свога јединог сина Јована. Када је Предојевић ...

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hivzija Hasandedić (1990). Muslimanska baština u istočnoj Hercegovini (Muslim heritage in eastern Herzegovina). El-Kalem, Sarajevo. p. 168.

- ↑ Ljiljana Ševo (1998). Monasteries and wooden churches of the Banja Luka eparchy. Glas Srpski. p. 28.

and the monastery of Rmanj was renewed by Hasan Pasha Predojević, as a chair to his brother, the monk Gavrilo Predojevic.

- ↑ Historical review. 37. Prosveta. 1991. p. 65.

Хасан-паша Предоевип до тада готово непозна- ти санцак-бег Сегедина.

- ↑ Mustafa Naima (1832). Annals of the Turkish Empire from 1591 to 1659 of the Christian Era. Oriental Translation Fund. p. 4.

- ↑ R. Lopašić, Spomenici Hrvatske krajine, III. (Zagreb, 1889)

- ↑ Vjekoslav Klaić: Povijest Hrvata od najstarijih vremena do svršetka XIX. stoljeća, Knjiga peta, Zagreb, 1988, p. 471

- ↑ Moačanin, Nenad: Some Problems of Interpretation of Turkish Sources concerning the Battle of Sisak in 1593, in: Nazor, Ante et al (ed.), Sisačka bitka 1593, Proceedings of the Meeting from 18–19 June 1993. Zagreb-Sisak (1994); pp. 125–130.

- ↑ Joseph Hammer-Purgstall (Freiherr von) (1829). Geschichte des osmanischen Reiches: Bd. 1574-1623. C. A. Hartleben.

- ↑ Mustafa Naima (1832). Annals of the Turkish Empire from 1591 to 1659 of the Christian Era. Oriental Translation Fund. p. 4.

- ↑ Mustafa Naima (1832). Annals of the Turkish Empire from 1591 to 1659 of the Christian Era. Oriental Translation Fund. p. 4.

- ↑ Mihailo Petrović (1941). Đerdapski ribolovi u prošlosti i u sadašnjosti. Izd. Zadužbine Mikh. R. Radivojeviča.

- ↑ Mustafa Naima (1832). Annals of the Turkish Empire from 1591 to 1659 of the Christian Era. Oriental Translation Fund. p. 4.

- ↑ Mustafa Naima (1832). Annals of the Turkish Empire from 1591 to 1659 of the Christian Era. Oriental Translation Fund. p. 5.

- ↑ Lopašić (1890). Bihać i Bihaćka krajina, mjestopisne i poviestne crtice. Matica hrvatska. pp. 60, 95.

- ↑ Izbor LASZOWSKI. Habsburski spomenici, I. pp. 176, 180.

- ↑ Milan Vasić (1995). Bosna i Hercegovina od srednjeg veka do novijeg vremena: međunarodni naučni skup 13-15. decembar 1994. Istorijski institut SANU.

- ↑ Dominik Mandić. Hrvati i Srbi: dva stara, razlicita naroda. p. 145.

- ↑ Mužić (Radoslav Lopašić) 2010, p. 34.

- ↑ Ivan Mužić (2010). Vlasi u starijoj hrvatskoj historiografiji (PDF) (in Croatian). Split: Muzej hrvatskih arheoloških spomenika. ISBN 978-953-6803-25-5.

- ↑ Luthar 2008, p. 215

- ↑ Hasan Celâl Güzel; Cem Oğuz; Osman Karatay; Murat Ocak (2002). The Turks: Ottomans (2 v. ). Yeni Türkiye.

- ↑ Ivo Goldstein: Croatia. A History, Transl. by Nikolina Jovanović, London: C. Hurst & Co., 1999, p. 39 ISBN 1-85065-525-1, ISBN 978-1-85065-525-1

- ↑ Alfred H. Loebl, Das Reitergefecht bei Sissek vom 22. Juni 1593. Mitteilungen des Instituts für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung IX (1915): p. 767-787.

- ↑ Peter Radics, Die Schlacht bei Sissek, 22. Juni 1593. (Ljubljana: Josef Blasnik, 1861)

- ↑ Dominik Mandić. Croats and Serbs: Two Old and Different Nations. p. 112.

- ↑ Mustafa Naima (1832). Annals of the Turkish Empire from 1591 to 1659 of the Christian Era. Oriental Translation Fund. p. 15.

- ↑ Bojan Baskar. "Ambivalent Dealings with an Imperial Past: The Habsburg Legacy and New Nationhood in ex-Yugoslavia" (PDF): 4.

- ↑ Đenana Buturović (1992). Bosanskomuslimanska usmena epika. Institut za književnost. p. 382.

- 1 2 D. Gavrilović (2003). "Elements of ethnic identification of the Serbs" (PDF). Niš: 720.

- ↑ Vjeran Kursar. OTAM, 34/Güz 2013, 115-161: Being an Ottoman Vlach: On Vlach Identity (Ies), Role and Status in Western Parts of the Ottoman Balkans (15th-18th Centuries). Bir Osmanlı Eflakı Olmak: Osmanlı Balkanlarının Batı Bölgelerinde Eflak Kimliği, Görevi ve Vaziyetine Dair (15.-18. Yüzyıllar). OTAM, Ankara Üniversitesi. p. 135.

- ↑ Vjeran Kursar. OTAM, 34/Güz 2013, 115-161: Being an Ottoman Vlach: On Vlach Identity (Ies), Role and Status in Western Parts of the Ottoman Balkans (15th-18th Centuries). Bir Osmanlı Eflakı Olmak: Osmanlı Balkanlarının Batı Bölgelerinde Eflak Kimliği, Görevi ve Vaziyetine Dair (15.-18. Yüzyıllar). OTAM, Ankara Üniversitesi. p. 115.

- ↑ Hamdija Kreševljaković (1914). Odakle su i sta su bili Bosne i Hercegovine Muslimani?. Hrvatska Svijest. p. 10.

- ↑ Krunoslav S. Draganović (1940). Hrvati i Herceg-Bosna: Povodom polemike o nacionalnoj pripadnosti Herceg-Bosne. Dr.: Vrček, Sarajevo. p. 20.

- ↑ Dominik Mandić. Hrvati i Srbi: dva stara, razlicita naroda. p. 256.