Happisburgh footprints

The Happisburgh footprints were a set of fossilized hominid footprints that date to the early Pleistocene. They were discovered in May 2013 in a newly uncovered sediment layer on a beach at Happisburgh (![]() i/ˈheɪz.bɜːrə/ HAYZ-bur-ə) in Norfolk, England, and were destroyed by the tide shortly afterwards.

i/ˈheɪz.bɜːrə/ HAYZ-bur-ə) in Norfolk, England, and were destroyed by the tide shortly afterwards.

Results of research on the footprints were announced on 7 February 2014, and identified them as dating to more than 800,000 years ago. They are the oldest known hominid footprints outside Africa.[1][2][3] Before the Happisburgh discovery, the oldest-known footprints in Britain were at Uskmouth in South Wales, from the Mesolithic and carbon-dated to 4,600 BC.[4] Prior to the Happisburgh discovery, the oldest known human footprints in Europe were a set of tracks found at the Roccamonfina volcano in Italy, dated to around 350,000 years ago.[5]

Discovery

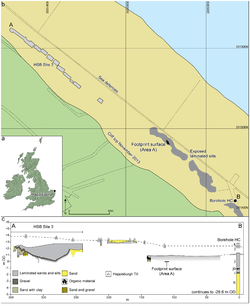

The footprints were discovered in May 2013 by Nicholas Ashton, curator at the British Museum, and Martin Bates from Trinity St David's University, who were carrying out research as part of the Pathways to Ancient Britain (PAB) project.[6] The footprints were found in sediment, partially covered by beach sand, at low tide on the foreshore at Happisburgh. The sediment had been laid down in the estuary of a long-vanished river and subsequently been covered by sand, preserving its surface. The layer of sediment underlies a cliff on the beach, but after stormy weather the protective layer of sand was washed away and the sediment exposed.[3][7] Because of the softness of the sediment, which lay below the high tide mark, tidal action eroded it, and within two weeks the footprints had been destroyed.[1]

Although the researchers were unable to preserve the footprints, they worked during periods of low tide, often in pouring rain, to record 3D images of all the footprints by using photogrammetry. The images were analysed by Isabelle De Groote of Liverpool John Moores University, who was able to confirm that the hollows in the sediment were hominin footprints.[1][8]

Facts concerning the discovery were published by Ashton and other members of the research team in February 2014 in the science journal PLOS ONE.[9]

Description

.png)

Approximately fifty footprints were found in an area measuring nearly 40 square metres (430 sq ft). Twelve were largely complete and two showed details of toes.[10] The footprints of approximately five individuals have been identified, including adults and children. The footprints measured between 140 and 260 millimetres (5.5 and 10.2 in), thought to equate to heights between 0.9 and 1.7 metres (2 ft 11 in and 5 ft 7 in). It is believed that the individuals who made them were from the species Homo antecessor,[8] known to have lived in the Atapuerca Mountains of Spain around 800,000 years ago. No hominin fossils have been found at Happisburgh.[7]

Analysis shows that the group of perhaps five individuals were walking in a southerly direction (upstream) along mudflats in the estuary of an early path of the River Thames that flowed into the sea farther north than it does today when south-east Britain was joined to the European continent.[8][11] Archaeologists have speculated that the group was searching the mudflats for seafood such as lugworms, shellfish, crabs, and seaweed. It is possible that the group might have lived on an island in the estuary that provided safety from predators, and were travelling from their island base to the shore at low tide.[10]

Dating

The Happisburgh site is too old to date using radiocarbon dating, which is not suitable for sites older than approximately 50,000 years. Dating the site has instead been based upon stratigraphy, palaeomagnetism, and the evidence of fossil flora and fauna in the sediments. The combined evidence suggests that the sediments were laid down at the end of a period of reversed magnetism between 780,000 and 1 million years ago.[12]

The exact date of the sediments that contained the footprints has not yet been determined. Magnetic signatures within the sedimentary deposits indicate they were laid down between the two most recent geomagnetic reversals – the Brunhes–Matuyama reversal around 780,000 years ago and the Jaramillo reversal around 950,000 to 1 million years ago. The evidence of fossil flora and fauna using indicators such as the fossilized teeth of voles, which provide very accurate dating evidence, pushes the lower limit back to at least 840,000 years ago. On this basis, two possible dates for the deposition of the sediments that the footprints were found in have been suggested, either c. 850,000 or c. 950,000 years ago, but further research is necessary to determine which is correct.[7][10]

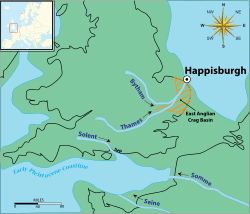

Pleistocene geography

At the time the Happisburgh hominins lived, a land bridge existed between Britain and France before the formation of the English Channel about 450,000 years ago. The River Thames flowed further north than it does today before converging with the ancient Bytham River,[13] while the landscape of a large part of modern-day East Anglia consisted of a series of clay ridges and troughs known as the East Anglian Crag Basin.[14] Happisburgh lay about 15 miles (24 km) further inland than it does today and was the site of an ancient estuary where the Bytham and Thames rivers converged to flow into what would then have been a maritime bay.[7]

When the footprints were made, the estuary occupied a grassy, open valley surrounded by pine forests, with a climate similar to that of modern southern Scandinavia. It would have been inhabited by mammoths, rhinos, hippos, giant deer and bison, which were preyed upon by sabre-toothed cats, lions, wolves and hyenas. As well as an abundant supply of game and edible plants, the river gravels were rich in flint deposits, which early humans would have found an invaluable resource.[7]

The Happisburgh finds mark the first time that evidence of early humans has been found so far north. Palaeontologists believed that hominins of the period required a much warmer climate but the inhabitants of prehistoric Happisburgh had adapted to the cold suggesting that they had developed advanced methods of hunting, clothing, sheltering and warming much earlier than previously thought.[7]

Archaeological context

Happisburgh has produced a number of significant archaeological finds over many years. As the shoreline is subject to severe coastal erosion, new material is constantly being exposed along the cliffs and on the beach. Prehistoric discoveries have been noted since 1820, when fishermen trawling oyster beds offshore found their nets had brought up teeth, bones, horns and antlers from elephants, rhinos, giant deer and other extinct species. An exceptionally high tide in February 1825 exposed more prehistoric remains when it swept away sediment that had buried an ancient landscape of fossilized tree stumps, animal bones and fir cones. In January 1877, a great storm swept huge ironstone slabs from the sea bed onto Happisburgh beach. The slabs preserved the impressions of leaves from oaks, elms, beeches, birches and willows that had lived thousands of years ago. Pleistocene bison bones found in the 1870s provided the first evidence of early human activity; a re-examination of the bones in 1999 found that they were scored with tell-tale cut marks, indicating that the animals had been butchered by humans with stone tools.[7]

In 2000, a black flint handaxe, dating to between 600,000 and 800,000 years ago, was found by a man walking on the beach. In 2012, for the television documentary Britain's Secret Treasures, the handaxe was selected by a panel of experts from the British Museum and the Council for British Archaeology as the most important item on a list of fifty archaeological discoveries made by members of the public.[15][16]

Since the axe's discovery, the palaeolithic history of Happisburgh has been the subject of the Ancient Human Occupation of Britain (AHOB) and Pathways to Ancient Britain (PAB) projects, directed by Nick Ashton and Chris Stringer, funded by grants from the Leverhulme Trust and Calleva Foundation. Between 2005 and 2010, eighty palaeolithic flint tools, mostly cores, flakes and flake tools, were excavated from the foreshore in sediment dating back to up to 950,000 years ago. The tools are believed to have been made by Homo antecessor, the same species thought to have made the footprints, and are the earliest artefacts to have been found in northern Europe.[7][17][18][19]

Archaeologists are hoping to reconstruct the environment in which the footprints were made by analysing remains of flora and fauna from the sediments. The remains of 15 species of mammals, 160 species of insects, and more than 100 species of plants have been recovered so far.[10]

Exhibition

The Happisburgh footprints feature in an exhibition, "Britain: One Million Years of the Human Story", at the Natural History Museum in London from 13 February 2014.[20]

Awards

The Happisburgh footprints won the 'Rescue Dig of the Year' title in the 2015 Current Archaeology Awards, voted for by the general public.[21]

See also

- Ancient footprints of Acahualinca — late Holocene human footprints found near the shore of Lake Managua in Nicaragua, dating to approximately 2,120 years ago.

- Eve's footprint — footprints of a single female found at Langebaan, South Africa in 1995, dating to approximately 117,000 years ago.

- Ileret — footprints of Homo erectus found at Ileret, Northern Kenya, dating to approximately 1.5 million years ago.

- Laetoli footprints — a line of hominid footprints, discovered at Laetoli, Tanzania by Mary Leakey in 1976, dating to approximately 3.6 million years ago.

- List of fossil sites (with link directory)

- List of hominina (hominid) fossils (with images)

References

- 1 2 3 Ghosh, Pallab. "Earliest footprints outside Africa discovered in Norfolk". BBC News. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ↑ Ashton N, Lewis SG, De Groote I, Duffy SM, Bates M, et al. (2014) "Hominin Footprints from Early Pleistocene Deposits at Happisburgh, UK", PLoS ONE 9(2): e88329. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088329

- 1 2 Ashton, Nicholas (7 February 2014). "The earliest human footprints outside Africa". British Museum. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ↑ "Uskmouth". Severn Estuary Levels Research Committee. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ↑ Bennett, Matthew R.; Morse, Sarita A. (2014). Human Footprints: Fossilised Locomotion?. Springer. p. 59. ISBN 978-3-319-08572-2.

- ↑ "Earliest human footprints outside Africa found in Norfolk". British Museum. 7 February 2014. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Colonising Britain: One million years of our human story". Current Archaeology (288): 14–21. March 2014.

- 1 2 3 "New discovery at Happisburgh: The earliest human footprints outside Africa". British Museum. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ↑ "Earliest human footprints outside Africa found – in Norfolk". Current Archaeology. 7 February 2014. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Keys, David (8 February 2014). "Meet the million-year-olds: Human footprints found in Britain are the oldest ever seen outside of Africa". The Independent.

- ↑ Connor, Steve (7 February 2014). "Norfolk footprints: Just who were Homo antecessor and how did they arrive in Britain?". The Independent.

- ↑ "Dating the site". British Museum. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ↑ "What do microfossils tell us about the first humans in Britain? Section 3. Happisburgh about 840,000-950,000 years ago". Natural History Museum, London. 14 November 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- ↑ Ehlers, J.; Gibbard, P.L.; Hughes, P.D. (2011), Quaternary Glaciations - Extent and Chronology: A closer look, Developments in Quaternary Science, UK: Elsevier Science, ISBN 9780444535375

- ↑ "Britain's Secret Treasures Episode Six". Portable Antiquities Scheme. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ↑ "NMS-ECAA52". Portable Antiquities Scheme. 12 July 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- ↑ "Excavation at Happisburgh". British Museum. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ↑ "Studying the finds". British Museum. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ↑ "Early humans in Europe and Asia". British Museum. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ↑ "Britain: One Million Years of the Human Story". Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- ↑ "Current Archaeology Press Release". Retrieved 9 March 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Happisburgh footprints. |

- The earliest human footprints outside Africa found in Norfolk — video of the footprints by the Natural History Museum, London

- Happisburgh project at the British Museum

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).

Coordinates: 52°49′32″N 1°32′06″E / 52.82542°N 1.53500°E