Hans-Ulrich Rudel

| Hans-Ulrich Rudel | |

|---|---|

Hans-Ulrich Rudel in 1944 | |

| Nickname(s) | Eagle of the Eastern Front |

| Born |

2 July 1916 Konradswaldau, German Empire |

| Died |

18 December 1982 (aged 66) Rosenheim, West Germany |

| Buried at | Dornhausen, near Gunzenhausen |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1936–45 |

| Rank | Oberst (Colonel) |

| Unit |

2.(F)/AufklGrp 121 StG 3, StG 2, SG 2 |

| Commands held | III./StG 2, SG 2 |

| Battles/wars |

See battles |

| Awards | Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Golden Oak Leaves, Swords, and Diamonds |

| Other work | Writer, businessman, founded relief organization for Nazi war criminals that helped fugitive escape to Latin America or the Middle East, and member of the German Reich Party |

Hans-Ulrich Rudel (2 July 1916 – 18 December 1982) was a Luftwaffe military aviator during World War II, a ground-attack pilot credited with the destruction of 519 tanks, as well as a number of ships. He also claimed 9 aerial victories, and the destruction of more than 800 vehicles of all types, over 150 artillery, anti-tank and anti-aircraft positions, 4 armored trains, and numerous bridges and supply lines.[Note 1] He flew 2,530 ground-attack missions exclusively on the Eastern Front, usually flying the Junkers Ju 87 "Stuka" dive bomber, and 430 missions flying the Focke-Wulf Fw 190.

Born in the Province of Silesia, Rudel volunteered for military service in the Luftwaffe in 1936. Following flight training, he served in an aerial reconnaissance unit at the outbreak of World War II in Europe. He transferred to the dive bomber force, and was posted to France. Rudel flew his first combat missions as a dive bomber pilot at the beginning of Operation Barbarossa in June 1941. On 23 September 1941, he was credited with severely damaging the Soviet battleship Marat, which effectively put her out of action for several months. He was posted to the Luftwaffe main testing ground at Rechlin, and experimented with the Bordkanone BK 3,7 equipped Ju 87G in the anti-tank role. Back on the Eastern Front, Rudel flew a Ju 87G in combat over the Kuban bridgehead, destroying numerous landing craft. He destroyed his 100th tank on 30 October 1943 and on 22 February 1944 was appointed Gruppenkommandeur (group commander) of III. Gruppe of Schlachtgeschwader 2 "Immelmann" (SG 2—2nd Ground Support Wing).

By 29 March 1944, Rudel was credited with over 200 tanks destroyed, and more than 1,800 combat missions logged. He was placed in command of SG 2 "Immelmann" in October 1944. Rudel flew his 2,400th combat mission on 22 December 1944, and on the following day destroyed his 463rd tank. For these achievements, he was awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Golden Oak Leaves, Swords, and Diamonds,[Note 2] presented to him by Adolf Hitler on 1 January 1945. Rudel was severely injured in combat on 8 February 1945, requiring the amputation of his right lower leg, and time in the hospital. On 25 March 1945, Rudel began flying again, before surrendering to US forces at the Kitzingen Airfield on 8 May 1945.

After his release from captivity in April 1946, Rudel owned and operated a haulage company in Coesfeld. In 1948, he emigrated to Argentina and founded the "Kameradenwerk", a relief organization for Nazi war criminals that helped fugitive Nazis escape to Latin America or the Middle East. Together with Willem Sassen, he helped conceal and protect Josef Mengele, a former SS doctor in the Auschwitz concentration camp, responsible for the selection of victims to be killed in the gas chambers. He also worked in the arms industry and as a military advisor. Through Juan Perón, the President of Argentina, he secured financially lucrative government military contracts. He was also active as a military adviser and arms dealer for the regime in Bolivia, for Augusto Pinochet in Chile, and for Alfredo Stroessner in Paraguay. Due to these activities, he was placed under observation by the US Central Intelligence Agency.

In the West German federal election of 1953, Rudel, who had returned to West Germany, was the top candidate for the far-right Deutsche Reichspartei (German Reich Party), but was not elected to the Bundestag. Following the Revolución Libertadora in 1955, the uprising that ended the second presidential term of Perón, Rudel was forced to move to Paraguay, where he frequently acted as a foreign representative for several German companies doing business in South America. In 1977, he became a spokesman for the Deutsche Volksunion (German People's Union), a nationalist political party founded by Gerhard Frey. Rudel died in Rosenheim in 1982, and was buried in Dornhausen.

Early life and career

Rudel was born on 2 July 1916 in Konradswaldau, Silesia, a province in the Kingdom of Prussia (present-day Grzędy) in the administrative district of Gmina Czarny Bór, within Wałbrzych County, Lower Silesian Voivodeship, in Poland. He was the third child of Lutheran minister Johannes Rudel and his wife Martha, née Mückner. He had two older sisters, Ingeborg and Johanna.[2] The children were raised in a number of different parishes, which included Schweidnitz (present-day Świdnica), Sagan (present-day Żagań), Niesky, Görlitz and Lauban (present-day Lubań).[3] As a boy, Rudel was a poor scholar, but a very keen sportsman. From 1922 to 1936, he attended the Volksschule, a primary school, and the humanities oriented Gymnasium, a secondary school, in Lauban, and graduated with his Abitur (university-preparatory high school diploma).[4] In late 1936, he attended the compulsory Reichsarbeitsdienst (Reich Labor Service) at Muskau, working on the banks of the Lusatian Neisse.[5]

On 4 December 1936, Rudel joined the Luftwaffe as a Fahnenjunker (officer cadet). Following basic training, his flight training began in June 1937 at the Luftkriegsschule 3 (3rd Air Warfare School) at Wildpark-Werder near Berlin.[5] In June 1938, now an Oberfähnrich (officer candidate), he joined I. Gruppe (1st group) of Sturzkampfgeschwader 168 (StG 168—168th Dive Bomber Wing) at Graz-Thalerhof, present-day Graz Airport.[Note 3] There, he was assigned to the 1. Staffel (1st squadron) for dive bombing training.[6] Rudel, as a teetotaler and non-smoker, was not well accepted among his peers. He also had difficulties learning the new techniques, and was considered unsuitable for combat flying, so on 1 December 1938, he was transferred to the Aufklärungsschule (Reconnaissance Flying School) at Hildesheim for air observer training in operational aerial reconnaissance.[7] He was promoted to Leutnant (second lieutenant) on 1 January 1939. In June 1939, he was posted to the 2. Staffel (2nd squadron) of Fernaufklärungsgruppe 121 (121st Long-Range Reconnaissance Group) at Prenzlau.[8]

World War II

On Friday 1 September 1939, German forces invaded Poland starting World War II in Europe. Shortly before the invasion, Aufklärungsgruppe 121 was moved to Schneidemühl, present-day Piła, at the time close to the Polish Corridor.[7] As an air observer, Rudel flew on long-range reconnaissance missions over Poland. He flew several missions over the Brest-Litovsk – Kovel – Lutsk railway line,[9] and earned the Iron Cross 2nd Class (Eisernes Kreuz zweiter Klasse) on 10 November 1939.[10] Following the invasion, Rudel submitted several requests for transfer back to the dive bomber force.[8] On 2 March 1940, he was posted to Fliegerausbildungs-Regiment 43 (43rd Aviators Training Regiment), based at Vienna-Stammersdorf and later at Crailsheim. There he served as a regimental adjutant.[10] During his time with Fliegerausbildungs-Regiment 43, Rudel participated in various sporting events, including a cross Vienna relay race, and on 6 October 1940, he took third place in the Silesian decathlon championship.[8] In late June 1940, he was transferred to I. Gruppe of Sturzkampfgeschwader 3 (StG 3—3rd Dive Bomber Wing), formerly his old unit I. Gruppe of StG 168, which had been renamed, and was based at Caen, France.[10]

Rudel did not fly operationally during the Battle of Britain, since he was still regarded a poor pilot.[8] Serving in a non-combatant role, he was promoted to Oberleutnant (first lieutenant) on 1 September 1940. In early 1941, he was transferred to the Stuka-Ergänzungsstaffel (Supplementary Dive Bomber Squadron) at Graz-Thalerhof, a specialized training unit for new dive bomber pilots.[11] There, according to his own account, he finally learned to master the Junkers Ju 87 two-man dive bomber. In mid-April 1941, he was assigned to I. Gruppe of Sturzkampfgeschwader 2 "Immelmann" (StG 2—2nd Dive Bomber Wing), named after the World War I fighter ace Max Immelmann, and based at Molaoi, Greece. His poor reputation as a pilot preceded him, and he spent the Battle of Crete in a non-combat role.[8] At the time, the Geschwader was commanded by Geschwaderkommodore (wing commander) Major Oskar Dinort, and Rudel's I. Gruppe was headed by Gruppenkommandeur (group commander) Hauptmann (captain) Hubertus Hitschhold.[12]

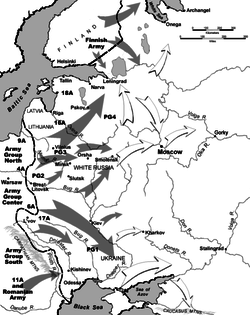

War against the Soviet Union

In June 1941, StG 2 "Immelmann" was moved to Raczki in preparation for Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union.[13] Initially for this campaign, the Geschwaderstab (headquarters unit), I. and III. Gruppe of StG 2 "Immelmann" had been placed under the control of VIII. Fliegerkorps (8th Air Corps), led by General der Flieger (General of the Aviators) Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen, subordinated to Luftflotte 2 (2nd Air Fleet) under the command of Generalfeldmarschall (Field Marshal) Albert Kesselring, and supported the northern or left flank of Army Group Center.[14] The main objective of this army group, under the command of Feldmarschall Fedor von Bock, was to capture the capital of the Soviet Union, Moscow.[15][16]

Rudel, who had been ordered to shuttle a Ju 87 to the production facility at Cottbus for a maintenance overhaul of the aircraft, heard over the radio news of the invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941. That day, he flew another aircraft to Insterburg, present-day Tschernjachowsk, and then southeast to Raczki. There, he was assigned to 1. Staffel commanded by Oberleutnant Ewald Janssen. As Janssen's wingman, Rudel flew his first four combat missions as a dive bomber pilot against Soviet tank and troop deployments in the vicinity of Grodno and Vawkavysk on 23 June 1941.[13][17] During the first two weeks of the campaign, StG 2 "Immelmann" flew ground support missions for armored units of Panzergruppe 3 (3rd Panzer Group) advancing towards Smolensk.[18] He was then transferred to the III. Gruppe of StG 2 "Immelmann", under command of Hauptmann Heinrich Brücker, and appointed Technischer Offizier (TO—Technical Officer), a role in which he was responsible for the supervision of all technical aspects, such as routine maintenance, servicing, and modifications of the Gruppe.[8] On 18 July 1941, he was awarded the Iron Cross 1st Class (Eisernes Kreuz erster Klasse) and the Front Flying Clasp of the Luftwaffe for Ground Attack Fighters in Gold (Frontflugspange für Schlachtflieger in Gold).[6]

By August 1941, Adolf Hitler had shifted VIII. Fliegerkorps northwards in support of Army Group North, under command of Feldmarschall Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb, in its attempt to capture Leningrad, present-day Saint Petersburg.[16] As a consequence of this decision, on 29 August 1941, III. Gruppe was ordered to an airfield south of Luga. There, Rudel flew numerous combat missions in support of the 16th Army and 18th Army advancing northwards.[19] The Soviet Navy Baltic Fleet, with its capital ships Marat and Oktyabrskaya Revolutsiya, supported by the heavy cruisers Kirov and Maxim Gorky, bombarded German forces on their advance towards Leningrad. Subsequently, Richthofen ordered StG 2 "Immelmann" to attack this Soviet naval task force. On 21 September 1941, Rudel flew his first mission against this task force, claiming a hit on the Marat with a 500 kg (1,100 lb) bomb.[20] On 23 September, StG 2 "Immelmann", now armed with 1,000 kg (2,200 lb) armor-piercing bombs, again attacked the Soviet ships based at Kronstadt harbor. Oberleutnant Lothar Lau scored a hit on Marat, causing a fire. Rudel also hit Marat, causing an enormous explosion that put her out of action for several months.[21][22][23] That day, III. Gruppe flew a second mission against the Soviet fleet at Kronstadt. Rudel did not participate in this mission. An accident while taxiing had rendered the aircraft of III. Gruppe commander, Hauptmann Ernst-Siegfried Steen, unserviceable, and Steen ordered Rudel to hand over his Ju 87 to him. Steen, with Unteroffizier Alfred Scharnowski, Rudel's regular air gunner, led the Gruppe in this attack. Flying into intense anti-aircraft fire over Kronstadt, Steen and Scharnowski took a direct hit while attacking Kirov, and both were killed in action.[24][25] In October 1941, Erwin Hentschel joined Rudel as his new radio operator and air gunner.[26]

Army Group Center opened Operation Taifun, the Battle of Moscow, on 30 September 1941 and VIII. Fliegerkorps was again placed under the command of Luftflotte 2.[16] On 20 October 1941, Rudel was awarded the Honor Goblet of the Luftwaffe (Ehrenpokal der Luftwaffe), and on 2 December 1941, the German Cross in Gold (Deutsches Kreuz in Gold), the first pilot of III. Gruppe to receive this distinction.[Note 4] By the end of December, he had flown his 400th mission, and on 6 January 1942 received the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross (Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes). The presentation was made by Richthofen on 15 January.[28] Rudel had been nominated for the Knight's Cross for severely damaging the battleships Marat and Oktyabrskaya Revolutsiya, sinking one heavy cruiser, and rendering another one unserviceable. In actions against land targets, he was credited with damaging or destroying 15 bridges, 23 artillery positions, 4 armored trains, and 17 tanks or assault guns.[8] In the winter of 1941–42, Rudel fought in the combat zones of the Volga–Daugave–Dnieper rivers near the Valdai Hills, in the vicinity of the Kholm and Demyansk Pockets, both pockets resulting from the German retreat following their defeat during the Battle of Moscow, in the area west of Rzhev, and over the railway line at Sychyovka.[29]

In early 1942, Rudel was granted home leave. During his vacation, he stayed with his parents in Alt-Kohlfurt, present-day Stary Węgliniec, and got married. He and his wife then took a skiing vacation in Tirol, Austria.[29] From March to August 1942, Rudel was appointed leader of the Ergänzungsstaffel at Graz-Thalerhof, and transferred with this Staffel to Sarabus, present-day Hwardijske, located 10 kilometers (6.2 miles) north of Simferopol on the Crimean peninsula. Beginning on 15 August 1942, flying with the Stuka-Ergänzungsstaffel and as Staffelkapitän (squadron leader) of 9. Staffel (9th squadron) of StG 2 "Immelmann", Rudel flew missions in the Caucasus and over the Black Sea.[30] On 23 September 1942, he damaged a 4,000 gross register tons (GRT) merchant ship in the harbor of Tuapse, and flew his 500th combat mission the following day. In early November 1942, Rudel was briefly hospitalized in Rostov-on-Don and treated for hepatitis. On 17 November 1942, Rudel was appointed Staffelkapitän of the 1. Staffel (1st squadron) of StG 2 "Immelmann", and flew with this unit in the Battle of Stalingrad.[31] Besides StG 2 "Immelmann", Richthofen had ordered the Stukas of II. Gruppe of Sturzkampfgeschwader 1 (StG 1—1st Dive Bomber Wing) and elements of Sturzkampfgeschwader 77 (StG 77—77th Dive Bomber Wing) to break Soviet opposition from the air.[32] On 25 November 1942, I. Gruppe of StG 2 "Immelmann" defended an airfield occupied by StG 1 at Oblivskaya against attacks from an Soviet cavalry division. That day, Rudel flew 17 combat missions in its defense.[33] Following his 750th combat mission, he was nominated for—but not awarded—the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves (Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes mit Eichenlaub) on 14 December 1942.[34]

Anti-tank operations

On 10 February 1943, Rudel flew his 1,000th combat mission from Gorlovka against forces of the 57th Army in the vicinity of Izium.[34][35] He was then sent on fourteen days home leave, which he spent at St. Anton, skiing on the Arlberg.[36]

Following this vacation, he was ordered to the Luftwaffe main testing ground at Rechlin. There, under the command of Hauptmann Hans-Karl Stepp, the Luftwaffe was experimenting with using the Ju 87 G in the anti-tank role, armed with two 37-millimeter (1.5-inch) Bordkanone BK 3,7 under-wing autocannons.[36] On 1 April 1943, he was promoted to Hauptmann with a rank age backdated to 1 April 1942.[30] The anti-tank unit Versuchskommando zur Panzerbekämpfung was later located at Bryansk-Desna, and then at an airfield at Kerch on the Kerch Peninsula. The airfield was also used by StG 2 "Immelmann", which at the time was flying missions against the Kuban bridgehead near Krymsk.[36] There, flying along with StG 2 "Immelmann", Rudel was credited with the destruction of 70 Soviet landing crafts, flying the cannon equipped Ju 87.[30] Some of these attacks were filmed by an onboard gun camera and shown in Die Deutsche Wochenschau, a newsreel released in German cinemas, its production supervised and censored by the Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda under Joseph Goebbels.[36] Der Adler, a biweekly Nazi propaganda magazine published by the Luftwaffe, also reported his actions in volume 12 of 1943. On 14 April 1943, Rudel was awarded the Oak Leaves to his Knight's Cross for his achievements in over 1,000 combat missions. He was the 229th member of the German armed forces to be so honored. Rudel received the Oak Leaves from Hitler personally at his office in the New Reich Chancellery in Berlin.[34]

On 5 July 1943, the first day of the Battle of Kursk, Rudel flew his first combat missions with the cannon equipped Ju 87 G against Soviet tanks in the area of Belgorod, destroying four T-34s on the first mission. In total, he was credited with twelve tanks destroyed that day.[37][Note 5] The same day, Rudel and his squadron flew in support of 2nd SS Panzer Division Das Reich and its advance towards Teterevino. At 10:30, a group of about 30 T-34s from the 5th Guards Tank Corps, possibly belonging to the 22nd Guards Tank Brigade, attacked SS-Obersturmbannführer Hans Albin Freiherr von Reitzenstein's Panzers. In two days, 5th Guards Tank Corps lost approximately 100 of its 200 tanks to Rudel's Stukas and SS Panzers.[39] On 17 July 1943, Hauptmann Walter Krauß, Gruppenkommandeur of III. Gruppe, was killed in action near Oryol. Two days later, Rudel was appointed leader of III. Gruppe. On the morning of 12 August 1943, Rudel and Hentschel respectively completed their 1,300th and 1,000th combat mission. Hentschel was the first air gunner to achieve this mark.[37]

On the morning of 9 October 1943, Rudel and Hentschel respectively completed their 1,500th and 1,200th combat mission. Rudel was the first pilot to achieve this mark. The event was celebrated at an airfield at Kostromka, south of Kryvyi Rih, and was attended by General der Flieger Kurt Pflugbeil, commanding general of the IV. Fliegerkorps (4th Air Corps).[40] StG 2 "Immelmann" was redesignated to Schlachtgeschwader 2 "Immelmann" (SG 2—2nd Ground Support Wing) on 18 October 1943. On 30 October 1943, Rudel, flying the Ju 87 G near Kirovohrad, was credited with the destruction of his 100th tank.[41] He flew his 1,600th mission in November 1943, and was credited with seven tanks destroyed on 23 November 1943.[42] For this achievement, on 25 November, he was awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords (Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes mit Eichenlaub und Schwertern), the 42nd member of the German armed forces to be so honored. On that day, Hentschel was awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross.[43] The presentation to Rudel and Hentschel was made by Hitler at the Führer Headquarter Wolfsschanze (Wolf's Lair) in Rastenburg, now Kętrzyn in Poland. At Rastenburg that day, Oberstleutnant (Lieutenant Colonel) Dietrich Hrabak, Geschwaderkommodore of Jagdgeschwader 52 (JG 52—52nd Fighter Wing), was also present at the award ceremony, and received the Oak Leaves to his Knight's Cross.[42]

Defeat on the Eastern Front

In January 1944, Rudel led III. Gruppe in defensive support of the 8th Army. During the Kirovohrad Offensive (1–16 January 1944), the 2nd Ukrainian Front, under command of Ivan Konev, attacked the German 8th Army. The Soviet operation was successful and led to German forces being encircled in the Battle of the Korsun–Cherkassy Pocket (24 January – 16 February 1944).[44] From 7 to 10 January 1944, Rudel was credited with the destruction of 17 Soviet tanks in these battles; he claimed his 150th tank victory on 11 January 1944, and flew his 1,700 mission on 16 January 1944.[45] He was officially appointed Gruppenkommandeur of III. Gruppe on 22 February 1944, and promoted to Major on 1 March 1944, with his seniority back dated to 1 October 1942.[30] On 20 March, Rudel landed behind Soviet lines to save a downed crew from captivity. This was his eighth mission of the day; the target area had been a bridge spanning the Dniester near Yampil. Unable to take off as the wheels of his aircraft had sunk into the soft ground, the four headed back to German held territory on foot. Pursued by Soviet troops, the men attempted to swim across the Dniester River. Rudel and two of the others made it across, while the fourth, Hentschel, drowned in the attempt.[26] Soon afterwards, the three were captured. Rudel was wounded by small arms fire in the shoulder as he made his escape and returned to German held territory the following day.[46] Upon his return, Ernst Gadermann, previously the troop doctor of III. Gruppe, joined Rudel as his new radio operator and air gunner.[47]

"Only he is lost who gives himself up for lost."[48]

Hans-Ulrich Rudel's motto in life

Rudel completed his 1,800 combat mission on 25 March 1944. The next day he flew several more sorties during the prelude of the First Jassy–Kishinev Offensive (8 April – 6 June 1944), and was credited with the destruction of 17 tanks at Fălești, 40 kilometers (25 mi) north of Iași. This achievement was mentioned in the Wehrmachtbericht, a propaganda radio report, the first of five such mentions, on 27 March 1944.[49] The next day, Rudel was again mentioned in the Wehrmachtbericht, which reported his 202nd tank kill. For this he was awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds (Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes mit Eichenlaub, Schwertern und Brillanten) on 29 March 1944. Rudel was the tenth member of the Wehrmacht, and the seventh pilot, who had received this award. The presentation was made at the Berghof, Hitler's home in the Obersalzberg of the Bavarian Alps near Berchtesgaden.[50] Following the presentation, Rudel went on vacation, and stayed with his wife and son at Alt-Kohlfurt. He then returned to the Eastern Front, flying to join his Gruppe, which was based at Huși, southeast of Iași.[51] Rudel flew his 2,000th combat mission on 1 June 1944, destroying his 301st tank that day, 78 of which had been destroyed with bombs and 223 with the 37 mm cannon.[30] This event earned him his third mention in the Wehrmachtbericht, which was broadcast on 3 June 1944. The Commander-in-Chief of the Luftwaffe, Reichsmarschall (Marshal of the Reich) Hermann Göring, presented Rudel with the Combined Pilots-Observation Badge in Gold with Diamonds (Flugzeugführer- und Beobachterabzeichen in Gold mit Brillanten), and the Golden Front Flying Clasp of the Luftwaffe for Ground Attack Fighters with Pennant "2,000" (Frontflugspange für Schlachtflieger in Gold mit Anhänger "2,000").[52]

On 13 July 1944, III. Gruppe was transferred from Huși, Romania to the central sector of the Eastern Front, where the Red Army was attacking towards the Vistula in Operation Bagration. Flying from an airfield at Chełm, the Gruppe targeted Rava-Ruska and other targets in the Ukraine and Belarus area. On 22 July, the Gruppe moved to Mielec in the Vistula-San triangle; from Mielec missions against armored columns at Jarosław, Rzeszów, and the Wisłok were flown.[53] On 5 August 1944, Rudel claimed 11 tanks destroyed, earning him his fourth mention in the Wehrmachtbericht. Rudel's number of tank kills had now reached 378, including 300 destroyed with the 37 mm cannon.[54] Fighting on the Courland front, he was credited with 8 tank kills on 14 August 1944, taking the total to 320 tank kills with the 37 mm cannon. On 19 August, Rudel's aircraft was hit by anti-aircraft fire in the vicinity of Ērgļi, Latvia. In the resulting forced landing, both he and Gadermann were injured, Rudel in the leg, and Gadermann suffering several broken ribs.[52] Rudel's unit was then ordered to transfer back to Romania, and then to Hungary. From 28 August onwards, Rudel operated from airfields at Buzău, 70 kilometers (43 mi) northeast of the vital oil refineries at Ploiești, namely Tășnad near Tokaj, Miskolc, Sajókaza northeast of Lake Balaton, Farmos near Szolnok, Vecsés near Budapest, and Börgönd near Székesfehérvár.[55]

Wing Commander

Rudel was promoted to Oberstleutnant on 1 September 1944, and appointed leader of SG 2 "Immelmann", replacing Stepp, on 1 October 1944.[56][Note 6] He handed over command of his III. Gruppe to Hauptmann Kurt Lau. On 17 November 1944, he was wounded in the thigh, and had to make an emergency landing at a fighter airfield near Budapest. Following his release from the hospital, he flew subsequent missions with his leg in a plaster cast.[58]

On 22 December 1944, Rudel completed his 2,400th combat mission, and the next day, he reported his 463rd tank destroyed. On 29 December 1944, Rudel was promoted to Oberst (colonel), and was awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Golden Oak Leaves, Swords, and Diamonds (Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes mit Goldenem Eichenlaub, Schwertern und Brillanten), the first and only person to receive this distinction. This award was presented to him by Hitler at the Adlerhorst, Hitler's headquarters in the Taunus mountains during the Battle of the Bulge, on 1 January 1945. On 14 January 1945, Rudel received the Hungarian Golden Medal for Bravery (Vitézségi Érem Arany), which was presented to him by Hungary's Head of State Ferenc Szálasi at Sopron, Hungary.[56]

On 8 February 1945, Rudel was credited with the destruction of 13 tanks near Lebus on the Oder River, earning him his fifth mention in the Wehrmachtbericht on 10 February 1945.[58] During the attack on the 13th tank, a 40 mm (1.6 in) shell hit his aircraft. He was badly wounded in the right foot, and crash landed inside German lines. His observer/gunner Gadermann stemmed the bleeding. Rudel was taken to a field hospital of the Waffen-SS at Seelow, where his leg had to be amputated below the knee.[59] He was then hospitalized in the Zoo flak tower in Berlin, and was flying operationally again with a modified rudder pedal on 25 March 1945. He claimed 26 more tanks destroyed by the end of the war.[60] On 19 April 1945, the day before Hitler's final birthday, Rudel spent the evening talking to Hitler in the Führerbunker, an air-raid shelter located near the Reich Chancellery in Berlin.[61] According to John Toland, author of the book Adolf Hitler, who based his statement on Rudel's book Stuka Pilot and personal interviews with Rudel, Hitler had ordered him to take charge of all jet fighter aircraft. Rudel refused, as he preferred flying to a desk job. By the time Rudel left, it was after midnight.[62]

On 8 May 1945, determined not to fall into Soviet hands, he left his ground personnel behind and led three Ju 87s and four Fw 190s westward from an airfield at Klecany, north of Prague, landing at Kitzingen airfield, which was held by the United States Army Air Forces 405th Fighter Group.[63][64] Rudel had his men lock the brakes and collapse the landing gear to render the aircraft useless; all but one obeyed his order and wiped off their undercarriage.[65] There he surrendered to US forces, and was taken prisoner of war. Over the next eleven months, he was held captive in Erlangen and Wiesbaden, then in prison camps in England and France, before he was taken to Fürth in Bavaria.[66]

Later life

In April 1946, Rudel was released from captivity at Fürth. While Rudel was interned, his family fleeing from the advancing Red Army had found refuge with Gadermann's parents in Wuppertal. There, Gadermann helped Rudel look for work. He was offered an office job, but he did not accept the position.[67] He then owned and operated a haulage company in Coesfeld.[37] In 1948, he emigrated to Argentina via the ratlines, travelling via the Austrian Zillertal to Italy. In Rome, with the help of South Tyrolean smugglers, and aided by the Austrian titular bishop Alois Hudal, he bought himself a fake Red Cross passport with the cover name "Emilio Meier", and took a flight from Rome to Buenos Aires, where he arrived on 8 June 1948.[68][69]

In South America

After Rudel moved to Argentina, he became a close friend and confidant of the President of Argentina Juan Perón, and Paraguay's dictator and Nazi Germany admirer Alfredo Stroessner. In Argentina, he founded the "Kameradenwerk" (lit. "comrades work" or "comrades act"), a relief organization for Nazi war criminals. Prominent members of the "Kameradenwerk" included SS officer Ludwig Lienhardt, whose extradition from Sweden had been demanded by the Soviet Union on war crime charges,[70] Kurt Christmann, a member of the Gestapo sentenced to 10 years for war crimes committed at Krasnodar, Austrian war criminal Fridolin Guth, and the German spy in Chile, August Siebrecht. The group maintained close contact with other internationally wanted fascists, such as Ante Pavelić, Carlo Scorza, Vittorio Mussolini, the son of Benito Mussolini, and Konstantin von Neurath. In addition to these war criminals that fled to Argentina, the "Kameradenwerk" also assisted Nazi criminals imprisoned in Europe, including Rudolf Hess and Karl Dönitz, with food parcels from Argentina and sometimes by paying their legal fees.[71] In Argentina, Rudel became acquainted with notorious Nazi concentration camp doctor and war criminal Josef Mengele.[72] Rudel, together with Willem Sassen, a former member of the Waffen-SS and a Wehrmacht propaganda and war correspondent unit, who initially worked as Rudel's driver and later for the Dürer-Verlag,[73] helped to relocate Mengele to Brazil by introducing him to Nazi supporter Wolfgang Gerhard.[74][75] In 1957, Rudel and Mengele together travelled to Chile to meet with Walter Rauff, the inventor of the mobile gas chamber.[76]

"What valuable substance of our people has often been saved of certain death by the Church in these years should justly remain unforgotten."

("Was in diesen Jahren durch die Kirche an wertvoller Substanz unseres Volkes oft vor dem sicheren Tode gerettet worden ist, soll billigerweise unvergessen bleiben.")[77]

Hans-Ulrich Rudel

In Argentina, Rudel lived in Villa Carlos Paz, roughly 36 kilometers (22 mi) from the populous Córdoba City, where he rented a house and operated a brickworks.[78] There, Rudel wrote his wartime memoirs Trotzdem ([Nevertheless] or [In Spite of Everything]).[79] The book was published in November 1949 by the Dürer-Verlag in Buenos Aires.[Note 7] Discussion ensued in Germany on Rudel being allowed to publish the book, because he was a known Nazi. In the book, he supported Nazi policies. This book was later re-edited and published in the United States, as the Cold War intensified, under the title, Stuka Pilot, which supported the German invasion of the Soviet Union. Pierre Clostermann, a French fighter pilot, had befriended Rudel and wrote the foreword to the French edition of his book Stuka Pilot.[81] In 1951, he published a pamphlet Dolchstoß oder Legende? ([Backstab or Legend?] or [Daggerthrust or Legend?]), in which he claimed that "Germany's war against Bolshevism was a defensive war", moreover, "a crusade for the whole world".[82] In the 1950s, Rudel became friends with Savitri Devi, a writer and proponent of Hinduism and Nazism and introduced her to a number of Nazi fugitives in Spain and the Middle East.[83]

With the help of Perón, Rudel secured financially lucrative governmental military contracts. He was also active as a military adviser and arms dealer for the regime and "Cocaine Generals" in Bolivia, for Augusto Pinochet in Chile and Stroessner in Paraguay.[84] In addition, he was in contact with Werner Naumann, formerly a State Secretary in Goebbels' Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda in Nazi Germany. Following the Revolución Libertadora in 1955, a military and civilian uprising that ended the second presidential term of Perón, Rudel was forced to leave Argentina and move to Paraguay. During the following years in South America, Rudel frequently acted as a foreign representative for several German companies, including Salzgitter AG, Dornier Flugzeugwerke, Focke-Wulf, Messerschmitt, Siemens and Lahmeyer International, a German consulting engineering firm.[85] Rudel's input was used during the development of the A-10 Thunderbolt II, a United States Air Force aircraft designed solely for close air support, including attacking tanks, armored vehicles and other ground targets.[86]

According to the historian Peter Hammerschmidt, based on files of the German Bundesnachrichtendienst (BND—Federal Intelligence Service) and the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), his research revealed that the BND, via the cover-up company "Merex", was in close contact with former members of the SS and the Nazi Party. In 1966, Merex, represented by Walter Drück, formerly a Generalmajor in the Wehrmacht and then an agent of the BND and under observation of the CIA, via contacts established by Rudel and Sassen, sold discarded equipment of the Bundeswehr (Federal Defence) to various dictators in Latin America. According to Hammerschmidt, Rudel assisted in establishing contact between Merex and Friedrich Schwend, a former member of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (Reich Main Security Office) and involved in Operation Bernhard. Schwend, according to Hammerschmidt, had close links with the military services of Peru and Bolivia. In the early sixties, Rudel, Schwend and Klaus Barbie, founded a company called "La Estrella", the star. This company employed a number of former SS officers, who, after the war, had found refuge in Latin America.[87][88] Rudel, through his involvement in La Estrella, was also in contact with Otto Skorzeny, who had his own network of former SS and Wehrmacht officers.[89]

Sport and political ambitions

Although missing one leg, he remained an active sportsman, playing tennis, skiing, and mountain climbing. In 1949, he competed in an international skiing competition held at Bariloche.[66] In this competition, Rudel took fourth place in the men's slalom, first place went to Stein Eriksen.[90] In 1951, he climbed the highest peak in the Americas, Aconcagua, at 6,960.8 meters (22,837 ft), and by extension the highest point in both the Western Hemisphere and the Southern Hemisphere. Due to deteriorating weather conditions, Rudel had to turn back short of the summit on 31 December 1951.[91] In 1953, Rudel ascended the Llullay-Yacu in the Argentine Andes, at 6,739 meters (22,110 feet) the fifth highest volcano, three times. On his second expedition, the team photographer Erwin Neubart was killed in a fall. His body was recovered and buried on the third expedition.[58] Rudel suffered a stroke on 26 April 1970.[92]

Rudel returned to West Germany in 1953 and became a leading member of the Neo-Nazi nationalist political party, the German Reich Party (DRP—Deutsche Reichspartei).[93] In the West German federal election of 1953, Rudel was the top candidate for the DRP, but was not elected to the Bundestag.[94] According to Josef Müller-Marein, journalist and editor-in-chief of Die Zeit, Rudel had an egocentric character. In his political speeches, Rudel made generalizing statements, claiming that he was speaking on behalf of most, if not all, former German soldiers of World War II. Rudel heavily criticized the Western Allies during World War II for not having supported Germany in its war against the Soviet Union. Rudel's political demeanor subsequently alienated him from his former comrades, foremost Gadermann. Müller-Marein concluded his article with the statement: "Rudel no longer has a Geschwader!"[95] In 1977, he became a spokesman for the Deutsche Volksunion (German People's Union), a nationalist political party founded by Gerhard Frey.[96] In 2004, Frey and Hajo Herrmann published an abstract of Rudel's biography in the book Helden der Wehrmacht – Unsterbliche deutsche Soldaten [Heroes of the Wehrmacht – Immortal German soldiers]. This publication was classified as a far-right wing publication by the German scholars Claudia Fröhlich and Horst-Alfred Heinrich.[97]

Public scandals

In October 1976, Rudel inadvertently triggered a chain of events, which were later dubbed the Rudel-Affäre (Rudel Scandal). Aufklärungsgeschwader 51 (51st Reconnaissance Wing) the latest unit to hold the name "Immelmann", held a reunion for members of the unit including those from World War II. The Secretary of State in the Federal Ministry of Defence, Hermann Schmidt authorized the event. Fearing that Rudel would spread Nazi propaganda on the German Air Force airbase in Bremgarten near Freiburg, Schmidt ordered that the meeting could not be held at the airbase. News of this decision reached Generalleutnant Walter Krupinski, at the time commanding general of NATO's Second Allied Tactical Air Force, and a former World War II fighter pilot. Krupinski contacted Gerhard Limberg, Inspector of the Air Force, requesting that the meeting be allowed to be held at the airbase. Limberg later confirmed Krupinski's request, and the meeting was held on Bundeswehr premises, a decision which Schmidt still did not agree to. Rudel attended the meeting, where besides signing his book and a few autographs, he refrained from making any political statements.[98]

During a routine press event, journalists, who had been briefed by Schmidt, questioned Krupinski and his deputy Karl Heinz Franke about Rudel. In this interview, the generals compared Rudel's past as a Nazi and Neo-Nazi supporter to the career of prominent Social Democrat leader Herbert Wehner, who had been a member of the German Communist Party in the 1930s, and who had lived in Moscow during World War II, where he was allegedly involved in NKVD operations. Calling Wehner an extremist, they described Rudel as an honorable man, who "hadn't stolen the family silver or anything else". When these remarks became public, the Federal Minister of Defense Georg Leber, complying with §50 of the Soldatengesetz (military law), ordered the generals into early retirement as of 1 November 1976. Leber, however, a member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), was heavily criticized for his actions by the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) opposition, and the scandal contributed to the minister's retirement in early 1978.[98] On 3 February 1977, the German Bundestag debated the scandal and its consequences. The Rudel Scandal subsequently triggered a military-tradition discussion, which the Federal Minister of Defense Hans Apel ended with the introduction of "Guidelines for Understanding and Cultivating Tradition" on 20 September 1982.[99]

During the 1978 FIFA World Cup, held in Argentina, Rudel visited the German national football team in their training camp in Ascochinga. The German media criticized the German Football Association (DFB—Deutscher Fußball-Bund), and viewed Rudel's visit as being sympathetic to the military dictatorship that ruled Argentina following the 1976 Argentine coup d'état. The president of the DFB, Hermann Neuberger, justified the visit, and stated that criticizing Rudel's visit was "an insult to all German soldiers" ("käme einer Beleidigung aller deutschen Soldaten gleich").[100] The German team captain, Berti Vogts, further fostered the criticism by stating after the World Cup: "Argentina is a country governed by law and order. I have not seen a single political prisoner." ("Land, in dem Ordnung herrscht. Ich habe keinen einzigen politischen Gefangenen gesehen")[101] Rudel had already visited a German team at a World Cup before. He was a spectator of the 1954 FIFA World Cup Final in Switzerland, and during the 1958 FIFA World Cup in Sweden, he visited the German team at Malmö following its 3:1 victory over Argentina on 8 June 1958. There he was welcomed by team manager Sepp Herberger.[102]

Personal life

Rudel was married three times. His 1942 marriage to Ursula, nicknamed "Hanne", produced two sons, Hans-Ulrich and Siegfried. They divorced in 1950. According to the news magazine Der Spiegel, one reason for the divorce was that his wife had sold some of his decorations, including the Oak Leaves with Diamonds, to an American collector, but she also refused to move to Argentina.[103] On 27 March 1951, Der Spiegel published Ursula Rudel's denial of selling his decorations, and further stated she had no intention of doing so.[104] Rudel married his second wife, Ursula née Daemisch in 1965. The marriage produced his third son, Christoph, born in 1969. Following his divorce in 1977, he married Ursula née Bassfeld.[105]

Death and funeral

Rudel died after suffering another stroke in Rosenheim on 18 December 1982,[82] and was buried in Dornhausen on 22 December 1982. During Rudel's burial ceremony, two Bundeswehr F-4 Phantoms appeared to make a low altitude flypast over his grave. Although Dornhausen was situated in the middle of a flightpath regularly flown by military aircraft, Bundeswehr officers denied deliberately flying aircraft over the funeral. Four mourners were photographed giving Nazi salutes at the funeral, and were investigated under a law banning the display of Nazi symbols. The Federal Minister of Defense Manfred Wörner declared that the flight of the aircraft had been a normal training exercise.[106]

Summary of military career

Rudel flew 2,530 combat missions on the Eastern Front of World War II. The majority of these were undertaken while flying the Junkers Ju 87, although 430 were flown in the ground-attack variant of the Focke-Wulf Fw 190. He was credited with the destruction of 519 tanks, severely damaging the battleship Marat, as well as sinking a cruiser, a destroyer and 70 landing craft. Rudel also claimed to have destroyed more than 800 vehicles of all types, over 150 artillery, anti-tank or anti-aircraft positions, 4 armored trains, as well as numerous bridges and supply lines. Rudel was also credited with 9 aerial victories, 7 of which were fighter aircraft and 2 Ilyushin Il-2s. He was shot down or forced to land 30 times due to anti-aircraft artillery, was wounded five times and rescued six stranded aircrew from enemy held territory.[56]

Awards

- Honor Goblet of the Luftwaffe (Ehrenpokal der Luftwaffe) as Oberleutnant in a Sturzkampfgeschwader (20 October 1941)[107]

- Wound Badge in Gold[108]

- Pilot/Observer Badge in Gold with Diamonds[108]

- German Cross in Gold on 2 December 1941 as Oberleutnant in the III./Sturzkampfgeschwader 2[Note 4]

- Iron Cross (1939)

- Front Flying Clasp of the Luftwaffe in Gold and Diamonds with Pennant "2000"

- Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Golden Oak Leaves, Swords, and Diamonds

- Knight's Cross on 6 January 1942 as Oberleutnant and Staffelkapitän of the 9./Sturzkampfgeschwader 2 "Immelmann"[110][111][Note 9]

- 229th Oak Leaves on 14 April 1943 as Oberleutnant and Staffelkapitän of the 1./Sturzkampfgeschwader 2 "Immelmann"[112][113][114]

- 42nd Swords on 25 November 1943 as Hauptmann and Gruppenkommandeur of the III./Sturzkampfgeschwader 2 "Immelmann"[115][111][Note 10]

- 10th Diamonds on 29 March 1944 as Major and Gruppenkommandeur of the III./Schlachtgeschwader 2 "Immelmann"[112][116][117]

- 1st Golden Oak Leaves on 29 December 1944 as Oberstleutnant and Geschwaderkommodore of Schlachtgeschwader 2 "Immelmann"[112][118][119]

- 8th (1st and only foreign) Hungarian Gold Medal of Bravery (14 January 1945)[10]

- Italian Silver Medal of Military Valor[108]

- Mentioned five times in the Wehrmachtbericht (27 March 1944, 28 March 1944, 3 June 1944, 6 August 1944, 10 February 1945)

Promotions

| 1 January 1939: | Leutnant (second lieutenant)[6] |

| 1 September 1940: | Oberleutnant (first lieutenant)[6] |

| 1 April 1943: | Hauptmann (captain), with a rank age of 1 April 1942[30] |

| 1 March 1944: | Major (major), with a rank age of 1 October 1942[30] |

| 1 September 1944: | Oberstleutnant (lieutenant colonel)[30] |

| 29 December 1944: | Oberst (colonel)[56] |

Notes

- ↑ For a list of Luftwaffe ground attack aces see List of German World War II ground attack aces.

- ↑ The Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Golden Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds was second only to the Grand Cross of the Iron Cross (Großkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes), which was awarded only to senior commanders for winning a major battle or campaign. The Grand Cross of the Iron Cross was awarded only to Hermann Göring (for the Luftwaffe's victories in the Battle of France), making the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Golden Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds the highest decoration the average soldier could achieve.[1]

- ↑ For an explanation of Luftwaffe unit designations see Organization of the Luftwaffe during World War II.

- 1 2 According to Patzwall and Scherzer, the presentation was made on 2 December 1941.[27] Just and Obermaier state that this occurred on 8 December 1941.[24][10]

- ↑ Bergström indicates that the exact date on which Rudel destroyed 12 tanks at Kursk is not entirely clear, circumstantial data indicates that it may have been 12 July and not 5 July.[38]

- ↑ According to Brütting, Rudel took command of SG 2 "Immelmann" on 1 August 1944.[57]

- ↑ The Dürer-Verlag (1947–1958) published a variety of apologia by former Nazis and their collaborators. Besides Rudel, among the early editors are Wilfred von Oven, the personal Press adjutant of Goebbels, and Naumann. Sassen convinced Adolf Eichmann to share his view on the Holocaust. Together with Eberhard Fritsch, a former Hitler Youth leader, Sassen began interviewing Eichmann in 1956 with the intent of publishing his views.[73] The Dürer-Verlag went bankrupt in 1958.[80]

- ↑ According to Thomas on 15 July 1941.[109]

- ↑ According to Scherzer as pilot and technical officer in the III./Sturzkampfgeschwader 2 "Immelmann".[112]

- ↑ According to Scherzer as leader of the III./Sturzkampfgeschwader 2 "Immelmann".[112]

Publications

- Wir Frontsoldaten zur Wiederaufrüstung [We Frontline Soldiers and Our Opinion on the Rearmament of Germany] (in German). Buenos Aires, Argentina: Dürer-Verlag. 1951. OCLC 603587732.

- Dolchstoß oder Legende? [Daggerthrust or Legend?]. Schriftenreihe zur Gegenwart, Nr. 4 (in German). Buenos Aires, Argentina: Dürer-Verlag. 1951. OCLC 23669099.

- Es geht um das Reich [It is about the Reich]. Schriftenreihe zur Gegenwart, Nr. 6 (in German). Buenos Aires, Argentina: Dürer-Verlag. 1952. OCLC 48951914.

- Trotzdem [Nevertheless] (in German). Göttingen, Germany: Schütz. 1966 [1949]. OCLC 2362892.

- Stuka Pilot. Translated by Hudson, Lynton. New York: Ballantine Books. 1958. OCLC 2362892.

- Hans-Ulrich Rudel—Aufzeichnungen eines Stukafliegers—Mein Kriegstagebuch [Hans-Ulrich Rudel—Notes by a Dive Bomber Pilot—My War Diary] (in German). Kiel, Germany: ARNDT-Verlag. 2001. ISBN 978-3-88741-039-1.

- Mein Leben in Krieg und Frieden [My life in war and peace] (in German). Rosenheim, Germany: Deutsche Verlagsgesellschaft. 1994. OCLC 34396545.

References

Citations

- ↑ Williamson & Bujeiro 2004, pp. 3, 7.

- ↑ Just 1986, p. 9.

- ↑ Just 1986, p. 11.

- ↑ Obermaier 1976, p. 30.

- 1 2 Stockert 1997, p. 106.

- 1 2 3 4 Obermaier 1976, p. 34.

- 1 2 Just 1986, p. 12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Stockert 1997, p. 107.

- ↑ Just 1986, p. 13.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Obermaier 1976, p. 31.

- ↑ Obermaier 1976, p. 32.

- ↑ Brütting 1992, pp. 266–267.

- 1 2 Brütting 1992, p. 68.

- ↑ Bergström & Mikhailov 2000, pp. 31, 264.

- ↑ Weal 2012, p. 7.

- 1 2 3 Bergström 2008, p. 13.

- ↑ Just 1986, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Murawski 2013, p. 11.

- ↑ Just 1986, p. 17.

- ↑ Just 1986, p. 18.

- ↑ Bergström & Mikhailov 2000, p. 187.

- ↑ Rohwer 2005, p. 102.

- ↑ Bergström 2007a, p. 85.

- 1 2 Just 1986, p. 20.

- ↑ Ward 2004, p. 220.

- 1 2 Ward 2004, p. 217.

- ↑ Patzwall & Scherzer 2001, p. 389.

- ↑ Brütting 1992, p. 75.

- 1 2 Just 1986, p. 22.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Obermaier 1976, p. 35.

- ↑ Stockert 1997, p. 108.

- ↑ Bergström et al. 2006, p. 214.

- ↑ Murawski 2013, p. 24.

- 1 2 3 Stockert 1997, p. 109.

- ↑ Weal 2012, p. 66.

- 1 2 3 4 Just 1986, p. 26.

- 1 2 3 Stockert 1997, p. 110.

- ↑ Bergström 2007b, p. 79.

- ↑ Nipe 2011, p. 167.

- ↑ Weal 2012, p. 75.

- ↑ Stockert 1997, p. 111.

- 1 2 Stockert 1997, p. 112.

- ↑ Just 1986, p. 28.

- ↑ Bergström 2008, p. 38.

- ↑ Stockert 1997, p. 113.

- ↑ Just 1986, pp. 29–30.

- ↑ Brütting 1992, p. 93.

- ↑ Bourne 2013, p. 277.

- ↑ Stockert 1997, p. 114.

- ↑ Stockert 1997, p. 115.

- ↑ Just 1986, p. 182.

- 1 2 Stockert 1997, p. 116.

- ↑ Just 1986, p. 207.

- ↑ Bergström 2008, p. 81.

- ↑ Just 1986, p. 211.

- 1 2 3 4 Obermaier 1976, p. 36.

- ↑ Brütting 1992, pp. 95, 266.

- 1 2 3 Just 1986, p. 43.

- ↑ Just 1986, p. 34.

- ↑ Hamilton 1996, p. 425.

- ↑ Fraschka 1994, p. 132.

- ↑ Toland 1977, p. 1183.

- ↑ Just 1986, p. 35, 43.

- ↑ Scutts 1999, p. 90.

- ↑ Weal 2003, p. 116.

- 1 2 Just 1986, p. 36.

- ↑ Müller-Marein 1953, p. 2.

- ↑ Goñi 2003, p. 287.

- ↑ Steinacher 2011, chpt. 1.6 "Fake Papers".

- ↑ Goñi 2003, p. 130.

- ↑ Goñi 2003, p. 134.

- ↑ Astor 1986, p. 170.

- 1 2 Benz 2013, p. 160.

- ↑ Levy 2006, p. 273.

- ↑ Posner & Ware 1986, p. 162.

- ↑ Goñi 2003, p. 290.

- ↑ Der Spiegel Volume 36/2001.

- ↑ Der Spiegel Volume 51/1950.

- ↑ Just 1986, p. 237.

- ↑ Benz 2013, p. 161.

- ↑ Just 1986, p. 272.

- 1 2 Der Spiegel Volume 52/1982.

- ↑ Goodrick-Clarke 2002, pp. 102–103.

- ↑ Goñi 2003, p. 288.

- ↑ Wulffen 2010, p. 139.

- ↑ Coram 2004, p. 235.

- ↑ Hammerschmidt 2014, pp. 254–257.

- ↑ Gessler 2011.

- ↑ Hammerschmidt 2014, p. 257.

- ↑ Just 1986, p. 239.

- ↑ Just 1986, pp. 36–37, 242.

- ↑ Just 1986, p. 37.

- ↑ Hamilton 1996, p. 426.

- ↑ Federal Election 1953.

- ↑ Müller-Marein 1953, pp. 1–3.

- ↑ Der Tagesspiegel—Visit.

- ↑ Fröhlich & Heinrich 2004, p. 134.

- 1 2 Die ZEIT Volume 46/1976.

- ↑ The Rudel-Scandal.

- ↑ Spiegel Online—WM-Anekdoten.

- ↑ Burkhardt 2010.

- ↑ Just 1986, p. 270.

- ↑ Der Spiegel Volume 48/1950.

- ↑ Der Spiegel Volume 13/1951.

- ↑ Neitzel, Sönke 2005, p. 160.

- ↑ Der Spiegel Volume 1/1983.

- ↑ Patzwall 2008, p. 174.

- 1 2 3 4 Berger 1999, p. 297.

- 1 2 Thomas 1998, p. 229.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, p. 366.

- 1 2 Von Seemen 1976, p. 15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Scherzer 2007, p. 643.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, p. 68.

- ↑ Von Seemen 1976, p. 34.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, p. 41.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, p. 37.

- ↑ Von Seemen 1976, p. 12.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, p. 35.

- ↑ Von Seemen 1976, p. 11.

Bibliography

- Astor, Gerald (1986). The Last Nazi: Life and Times of Doctor Joseph Mengele. Weidenfeld. ISBN 978-0-297-78853-9.

- Benz, Wolfgang (2013). Handbuch des Antisemitismus [Handbook of Anti-Semitism] (in German). 6. Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter Saur. ISBN 978-3-11-030535-7.

- Berger, Florian (1999). Mit Eichenlaub und Schwertern. Die höchstdekorierten Soldaten des Zweiten Weltkrieges [With Oak Leaves and Swords. The Highest Decorated Soldiers of the Second World War] (in German). Vienna, Austria: Selbstverlag Florian Berger. ISBN 978-3-9501307-0-6.

- Bergström, Christer; Mikhailov, Andrey (2000). Black Cross / Red Star Air War Over the Eastern Front, Volume I, Operation Barbarossa 1941. Pacifica, California: Pacifica Military History. ISBN 978-0-935553-48-2.

- Bergström, Christer; Dikov, Andrey; Antipov, Vlad; Sundin, Claes (2006). Black Cross / Red Star Air War Over the Eastern Front, Volume 3, Everything for Stalingrad. Hamilton MT: Eagle Editions. ISBN 978-0-9761034-4-8.

- Bergström, Christer (2007a). Barbarossa—The Air Battle: July–December 1941. Hersham, Surrey: Classic Publications. ISBN 978-1-85780-270-2.

- Bergström, Christer (2007b). Kursk—The Final Air Battle: July 1943. Hersham, Surrey: Classic Publications. ISBN 978-1-903223-88-8.

- Bergström, Christer (2008). Bagration to Berlin—The Final Air Battles in the East: 1944–1945. Burgess Hill: Classic Publications. ISBN 978-1-903223-91-8.

- Bourne, Merfyn (2013). The Second World War in the Air: The Story of Air Combat in Every Theatre of World War Two. Leicester: Troubador Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78088-441-7.

- Brütting, Georg (1992) [1976]. Das waren die deutschen Stuka-Asse 1939 – 1945 [These were the German Stuka Aces 1939 – 1945] (in German) (7th ed.). Stuttgart, Germany: Motorbuch. ISBN 978-3-87943-433-6.

- Burkhardt, Peter (17 May 2010). "Jubel in Hörweite der Folterkammern" [Cheers within hearing distance of the torture chambers]. Süddeutsche Zeitung (in German). ISSN 0174-4917. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- Coram, Robert (2004). Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War. Back Bay Books. ISBN 978-0-316-79688-0.

- Fellgiebel, Walther-Peer (2000) [1986]. Die Träger des Ritterkreuzes des Eisernen Kreuzes 1939–1945 — Die Inhaber der höchsten Auszeichnung des Zweiten Weltkrieges aller Wehrmachtteile [The Bearers of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross 1939–1945 – The Owners of the Highest Award of the Second World War of all Wehrmacht Branches] (in German). Friedberg, Germany: Podzun-Pallas. ISBN 978-3-7909-0284-6.

- Fraschka, Günther (1994). Knights of the Reich. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Military/Aviation History. ISBN 978-0-88740-580-8.

- Fröhlich, Claudia; Heinrich, Horst-Alfred (2004). Geschichtspolitik: Wer sind ihre Akteure, wer ihre Rezipienten? [Political History: Who are their Players, who their Recipients?] (in German). Stuttgart, Germany: Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 978-3-515-08246-4.

- Gessler, Philipp (20 June 2011). "Code-Name "Uranus"". Die Tageszeitung (in German). ISSN 0931-9085. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- Goñi, Uki (2003) [2002]. The Real Odessa: How Perón Brought the Nazi War Criminals to Argentina. London, UK: Granta. ISBN 978-1-86207-552-8.

- Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas (2002). Black Sun: Aryan Cults, Esoteric Nazism, and the Politics of Identity. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-3155-0.

- Hamilton, Charles (1996). Leaders & Personalities of the Third Reich, Vol. 2. R. James Bender Publishing. ISBN 978-0-912138-66-4.

- Hammerschmidt, Peter (2014). Deckname Adler: Klaus Barbie und die westlichen Geheimdienste [Codename Eagle: Klaus Barbie and the Western Intelligence Agencies] (in German). Frankfurt am Main, Germany: S. Fischer. ISBN 978-3-10-029610-8.

- Just, Günther (1986). Stuka Pilot Hans Ulrich Rudel. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Military History. ISBN 978-0-88740-252-4.

- Levy, Alan (2006) [1993]. Nazi Hunter: The Wiesenthal File (Revised 2002 ed.). London: Constable & Robinson. ISBN 978-1-84119-607-7.

- Müller-Marein, Josef (27 August 1953). "Der Fall Rudel" [The Case Rudel]. Die Zeit (in German). ISSN 0044-2070. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- Murawski, Marek J. (2013). St.G 2 "Immelmann". Lublin, Poland: Kagero. ISBN 978-83-62878-51-2.

- Neitzel, Sönke (2005), "Rudel, Hans-Ulrich", Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB) (in German), 22, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 160–161; (full text online)

- Nipe, George M. (2011). Blood, Steel and Myth—The II. SS-Panzer-Korps and the road to Prochorowka, July 1943. Stamford, CT: RZM Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9748389-4-6.

- Obermaier, Ernst (1976). Die Ritterkreuzträger der Luftwaffe 1939–1945 Band II Stuka- und Schlachtflieger [The Knight's Cross Bearers of the Luftwaffe 1939–1945 Volume II Dive Bomber and Attack Aircraft] (in German). Mainz, Germany: Verlag Dieter Hoffmann. ISBN 978-3-87341-021-3.

- Patzwall, Klaus D. (2008). Der Ehrenpokal für besondere Leistung im Luftkrieg [The Honor Goblet for Outstanding Achievement in the Air War] (in German). Norderstedt, Germany: Verlag Klaus D. Patzwall. ISBN 978-3-931533-08-3.

- Patzwall, Klaus D.; Scherzer, Veit (2001). Das Deutsche Kreuz 1941 – 1945 Geschichte und Inhaber Band II [The German Cross 1941 – 1945 History and Recipients Volume 2] (in German). Norderstedt, Germany: Verlag Klaus D. Patzwall. ISBN 978-3-931533-45-8.

- Posner, Gerald L.; Ware, John (1986). Mengele: The Complete Story. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-050598-8.

- Rohwer, Jürgen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two (Third Revised ed.). Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-119-8.

- Saueier, Hans (1976). "Die Generäle von gestern". Die Zeit (in German). 46. ISSN 0044-2070. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- Scherzer, Veit (2007). Die Ritterkreuzträger 1939–1945 Die Inhaber des Ritterkreuzes des Eisernen Kreuzes 1939 von Heer, Luftwaffe, Kriegsmarine, Waffen-SS, Volkssturm sowie mit Deutschland verbündeter Streitkräfte nach den Unterlagen des Bundesarchives [The Knight's Cross Bearers 1939–1945 The Holders of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross 1939 by Army, Air Force, Navy, Waffen-SS, Volkssturm and Allied Forces with Germany According to the Documents of the Federal Archives] (in German). Jena, Germany: Scherzers Militaer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-938845-17-2.

- Scutts, Jerry (1999). P-47 Thunderbolt Aces of the Ninth and Fifteenth Air Forces. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85532-906-5.

- Stockert, Peter (1997). Die Eichenlaubträger 1939–1945 Band 3 [The Oak Leaves Bearers 1939–1945 Volume 3] (in German). Bad Friedrichshall, Germany: Friedrichshaller Rundblick. ISBN 978-3-932915-01-7.

- Steinacher, Gerald (2011). Nazis on the Run: How Hitler's Henchmen Fled Justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-165377-3.

- Thomas, Franz (1998). Die Eichenlaubträger 1939–1945 Band 2: L–Z [The Oak Leaves Bearers 1939–1945 Volume 2: L–Z] (in German). Osnabrück, Germany: Biblio-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7648-2300-9.

- Toland, John (1977) [1976]. Adolf Hitler. New York: Ballantine. ISBN 978-0-345-25899-1.

- Von Seemen, Gerhard (1976). Die Ritterkreuzträger 1939–1945 : die Ritterkreuzträger sämtlicher Wehrmachtteile, Brillanten-, Schwerter- und Eichenlaubträger in der Reihenfolge der Verleihung : Anhang mit Verleihungsbestimmungen und weiteren Angaben [The Knight's Cross Bearers 1939–1945 : The Knight's Cross Bearers of All the Armed Services, Diamonds, Swords and Oak Leaves Bearers in the Order of Presentation: Appendix with Further Information and Presentation Requirements] (in German). Friedberg, Germany: Podzun-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7909-0051-4.

- Ward, John (2004). Hitler's Stuka Squadrons: The Ju 87 at War, 1936–1945. St. Paul, MN: MBI. ISBN 978-0-7603-1991-8.

- Weal, John (2003). Luftwaffe Schlachtgruppen. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-608-9.

- Weal, John (2012). Junkers Ju 87 Stukageschwader of the Russian Front. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78200-530-8.

- Williamson, Gordon; Bujeiro, Ramiro (2004). Knight's Cross and Oak Leaves Recipients 1939–40. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-641-6.

- Wulffen, Bernd (2010). Deutsche Spuren in Argentinien—Zwei Jahrhunderte wechselvoller Beziehungen [German Traces in Argentina—Two Centuries of Eventful Relations]. Berlin, Germany: Ch. Links Verlag. ISBN 978-3-86153-573-7.

- "Wahl zum 2. Deutschen Bundestag am 6. September 1953" (in German). Bundeswahlleiter. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- "Die Rudel-Affäre" [The Rudel-Scandal]. Bundeswehr (in German). 1 October 1976. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- "Hans Ulrich Rudel". Der Spiegel (in German). 48. 1950. ISSN 0038-7452. Retrieved 17 August 2014.

- "Kampfflieger—Trotzdem zu spät" [Combat Flyer—Nevertheless, too late]. Der Spiegel (in German). 51. 1950. ISSN 0038-7452. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- "Ursula Rudel". Der Spiegel (in German). 13. 1951. ISSN 0038-7452. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- "Hans-Ulrich Rudel". Der Spiegel (in German). 52. 1982. ISSN 0038-7452. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- "Letzter Flug" [Last Flight]. Der Spiegel (in German). 1. 1983. ISSN 0038-7452. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- "Im Visier der Nazi-Jäger" [In the Focus of Nazi Hunters]. Der Spiegel (in German). 36. 2001. ISSN 0038-7452. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- Schulze-Marmeling, Dietrich (2 June 2008). "Ein Besuch bei alten Kameraden — Der Nazi Rudel kam 1978" [A Visit to old Comrades — The Nazi Rudel came in 1978]. Der Tagesspiegel (in German). ISSN 0941-9373. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- "WM-Anekdoten: Ein Jahrhundertspiel und ein Jahrhundertskandal" [WM Anecdotes: A Match of the Century and a Century Scandal]. Spiegel Online (in German). Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- Die Wehrmachtberichte 1939–1945 Band 3, 1. Januar 1944 bis 9. Mai 1945 [The Wehrmacht Reports 1939–1945 Volume 3, 1 January 1944 to 9 May 1945] (in German). München, Germany: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag GmbH & Co. KG. 1985. ISBN 978-3-423-05944-2.

Further reading

- Rees, Philip (1991). Biographical Dictionary of the Extreme Right Since 1890. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-13-089301-7.

- Tauber, Kurt P. (1967). Beyond Eagle and Swastika: German Nationalism Since 1945. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press. OCLC 407180.

External links

- Hans-Ulrich Rudel in the German National Library catalogue

- "Hans Rudel" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- "Hans-Ulrich Rudel". Der Spiegel (in German). 19. 1953. ISSN 0038-7452. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- "Hans-Ulrich Rudel". Der Spiegel (in German). 20. 1956. ISSN 0038-7452. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- "Hans-Ulrich Rudel". Der Spiegel (in German). 35. 1957. ISSN 0038-7452. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- "Hans-Ulrich Rudel". Der Spiegel (in German). 16. 1959. ISSN 0038-7452. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- "Dunkle Seite des Mondes" [Dark Side of the Moon]. Der Spiegel (in German). 12. 1992. ISSN 0038-7452. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

| Military offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Oberstleutnant Hans-Karl Stepp |

Commander of Schlachtgeschwader 2 "Immelmann" 1 October 1944 – 8 February 1945 |

Succeeded by Major Friedrich Lang |

| Preceded by Oberstleutnant Kurt Kuhlmey |

Commander of Schlachtgeschwader 2 "Immelmann" April 1945 – 8 May 1945 |

Succeeded by none |