Haloarchaea

| Haloarchaea | |

|---|---|

| |

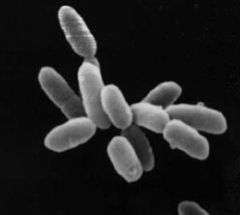

| Halobacterium sp. strain NRC-1, each cell about 5 µm in length. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Archaea |

| Kingdom: | Archaea |

| Phylum: | Euryarchaeota |

| Class: | Halobacteria Grant et al. 2002 |

| Order | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

In taxonomy, the Halobacteria (also Halobacteriacea) are a class of the Euryarchaeota,[1] found in water saturated or nearly saturated with salt. Halobacteria are now recognized as archaea, rather than bacteria. The name 'halobacteria' was assigned to this group of organisms before the existence of the domain Archaea was realized, and remains valid according to taxonomic rules. In a non-taxonomic context, halophilic archaea are referred to as haloarchaea to distinguish them from halophilic bacteria.

These microorganisms are members of the halophile community, in that they require high salt concentrations to grow. They are a distinct evolutionary branch of the Archaea, and are generally considered extremophiles, although not all members of this group can be considered as such.

Haloarchaea can grow aerobically or anaerobically. Parts of the membranes of haloarchaea are purplish in color, and large blooms of haloarchaea appear reddish, from the pigment bacteriorhodopsin, related to the retinal pigment rhodopsin which it uses to transform light energy into chemical energy by a process unrelated to chlorophyll-based photosynthesis.

Taxonomy

The extremely halophilic, aerobic members of Archaea are classified within the family Halobacteriaceae, order Halobacteriales in Class III. Halobacteria of the phylum Euryarchaeota (International Committee on Systematics of Prokaryotes, Subcommittee on the taxonomy of Halobacteriaceae). As of May 2016, the family Halobacteriaceae comprises 50 genera 213 species.

Domain : Archaea

Euryarchaeota

- Halobacteria

- Halobacteriales

- Halobacteriaceae

- Haladaptatus [Hap.]

- Haladaptatus cibarius

- Haladaptatus litoreus

- Haladaptatus pallidirubidus

- Haladaptatus paucihalophilus (Type species)

- Halalkalicoccus [Hac.]

- Halalkalicoccus jeotgali

- Halalkalicoccus paucihalophilus

- Halalkalicoccus tibetensis (Type species)

- "Halanaeroarchaeum" ["Haa".]

- "Halanaeroarchaeum sulfurireducens" (Type species) (IJSEM, in press)

- Halapricum [Hpr.]

- Halapricum salinum (Type species)

- Halarchaeum [Hla.]

- Halarchaeum acidiphilum (Type species)

- Halarchaeum grantii

- Halarchaeum nitratireducens

- Halarchaeum rubridurum

- Halarchaeum salinum

- Halarchaeum solikamskense

- Haloarchaeobius [Hab.]

- Haloarchaeobius amylolyticus

- Haloarchaeobius baliensis

- Haloarchaeobius iranensis (Type species)

- Haloarchaeobius litoreus

- Haloarchaeobius salinus

- Haloarcula [Har.]

- Haloarcula amylolytica

- Haloarcula argentinensis

- Haloarcula hispanica

- Haloarcula japonica

- Haloarcula marismortui

- Haloarcula quadrata

- Haloarcula salaria

- Haloarcula tradensis

- Haloarcula vallismortis (Type species)

- Halobacterium [Hbt.] (Type genus)

- Halobacterium jilantaiense

- Halobacterium noricense

- "Halobacterium piscisalsi" (subjective junior synonym of Halobacterium salinarum)[2]

- Halobacterium ruburm

- Halobacterium salinarum (Type species)

- Halobaculum [Hbl.]

- Halobaculum gomorrense (Type species)

- Halobaculum magnesiiphilum

- Halobellus [Hbs.]

- Halobellus clavatus (Type species)

- Halobellus inordinatus

- Halobellus limi

- Halobellus litoreus

- Halobellus ramosii

- Halobellus rarus

- Halobellus rufus

- Halobellus salinus

- Halobiforma [Hbf.]

- Halobiforma haloterrestris (Type species)

- Halobiforma lacisalsi

- Halobiforma nitratireducens

- Halocalculus [Hcl.]

- Halocalculus aciditolerans (Type species)

- Halococcus [Hcc.]

- Halococcus agarilyticus

- Halococcus dombrowskii

- Halococcus hamelinensis

- Halococcus morrhuae (Type species)

- Halococcus qingdaonensis

- Halococcus saccharolyticus

- Halococcus salifodinae

- Halococcus sediminicola

- Halococcus thailandensis

- Haloferax [Hfx.]

- Haloferax alexandrinus

- Haloferax chudinovii

- Haloferax denitrificans

- Haloferax elongans

- Haloferax gibbonsii

- Haloferax larsenii

- Haloferax lucentense

- Haloferax mediterranei

- Haloferax mucosum

- Haloferax prahovense

- Haloferax sulfurifontis

- Haloferax volcanii (Type species)

- Halogeometricum [Hgm.]

- Halogeometricum borinquense (Type species)

- Halogeometricum limi

- Halogeometricum pallidum

- Halogeometricum rufum

- Halogranum [Hgn.]

- Halogranum amylolyticum

- Halogranum gelatinilyticum

- Halogranum rubrum (Type species)

- Halogranum salarium

- Halohasta [Hht.]

- Halohasta litorea (Type species)

- Halohasta litchfieldiae

- Halolamina [Hlm.]

- Halolamina pelagica (Type species)

- Halolamina rubra

- Halolamina salifodinae

- Halolamina salina

- Halolamina sediminis

- Halomarina [Hmr.]

- Halomarina oriensis (Type species)

- Halomicroarcula [Hma.]

- Halomicroarcula limicola

- Halomicroarcula pellucida (Type species)

- Halomicroarcula salina

- Halomicrobium [Hmc.]

- Halomicrobium katesii

- Halomicrobium mukohataei (Type species)

- Halomicrobium zhouii

- Halonotius [Hns.]

- Halonotius pteroides (Type species)

- "Haloparvum" ["Hpv".]

- "Haloparvum sedimenti" (Type species) (IJSEM, in press)

- Halopelagius [Hpl.]

- Halopelagius inordinatus (Type species)

- Halopelagius fulvigenes

- Halopelagius longus

- Halopenitus [Hpt.]

- Halopenitus malekzadehii

- Halopenitus persicus (Type species)

- Halopenitus salinus

- Halopiger [Hpg.]

- Halopiger aswanensis

- Halopiger salifodinae

- Halopiger xanaduensis (Type species)

- Haloplanus [Hpn.]

- Haloplanus aerogenes

- Haloplanus litoreus

- Haloplanus natans (Type species)

- Haloplanus ruber

- Haloplanus salinus

- Haloplanus vescus

- Haloquadratum [Hqr.]

- Haloquadratum walsbyi (Type species)

- Halorhabdus [Hrd.]

- Halorhabdus tiamatea

- Halorhabdus utahensis (Type species)

- "Halorhabdus rudnickae" (Syst Appl Microbiol., in press)

- Halorientalis [Hos.]

- Halorientalis brevis

- Halorientalis persicus

- Halorientalis regularis (Type species)

- Halorubellus [Hrb.]

- Halorubellus litoreus

- Halorubellus salinus (Type species)

- Halorubrum [Hrr.]

- Halorubrum aquaticum

- Halorubrum aidingense

- Halorubrum alkaliphilum

- Halorubrum arcis

- Halorubrum californiense

- Halorubrum chaoviator

- Halorubrum cibi

- Halorubrum coriense

- Halorubrum distributum

- Halorubrum ejinorense

- Halorubrum ezzemoulense

- Halorubrum gandharaense

- Halorubrum halodurans

- Halorubrum halophilum

- Halorubrum kocurii

- Halorubrum lacusprofundi

- Halorubrum laminariae

- Halorubrum lipolyticum

- Halorubrum litoreum

- Halorubrum luteum

- Halorubrum orientale

- Halorubrum persicum

- Halorubrum rubrum

- "Halorubrum rutilum" (Arch Microbiol.,2015, 197(10):1159-1164)

- Halorubrum saccharovorum (Type species)

- Halorubrum salinum

- Halorubrum sodomense

- Halorubrum tebenquichense

- Halorubrum terrestre

- Halorubrum tibetense

- Halorubrum trapanicum

- Halorubrum vacuolatum

- Halorubrum yunnanense

- Halorubrum xinjiangense

- Halorussus [Hrs.]

- Halorussus amylolyticus

- Halorussus rarus

- Halorussus ruber

- "Halosiccatus" ["Hsc".]

- "Halosiccatus urmianus" (Type species) (IJSEM, in press)

- Halosimplex [Hsx.]

- Halosimplex carlsbadense (Type species)

- Halosimplex litoreum

- Halosimplex pelagicum

- Halosimplex rubrum

- Halostagnicola [Hst.]

- Halostagnicola alkaliphila

- Halostagnicola bangensis

- Halostagnicola kamekurae

- Halostagnicola larsenii (Type species)

- "Halostella" ["Hsl".]

- "Halostella salina" (Type species) (IJSEM, in press)

- Haloterrigena [Htg.]

- Haloterrigena daqingensis

- Haloterrigena hispanica

- Haloterrigena jeotgali

- Haloterrigena limicola

- Haloterrigena longa

- Haloterrigena saccharevitans

- Haloterrigena salina

- Haloterrigena thermotolerans

- Haloterrigena turkmenica (Type species)

- Halovarius [Hvr.]

- Halovarius luteus (Type species)

- Halovenus [Hvn.]

- Halovenus aranensis (Type species)

- Halovenus rubra

- Halovenus salina

- Halovivax [Hvx.]

- Halovivax asiaticus (Type species)

- Halovivax cerinus

- Halovivax limisalsi

- Halovivax ruber

- Natrialba [Nab.]

- Natrialba aegyptia

- Natrialba asiatica (Type species)

- Natrialba chahannaoensis

- Natrialba hulunbeirensis

- Natrialba magadii

- Natrialba taiwanensis

- Natribaculum [Nbl.]

- Natribaculum breve (Type species)

- Natribaculum longum

- Natrinema [Nnm.]

- Natrinema altunense

- Natrinema ejinorense

- Natrinema gari

- Natrinema pallidum

- Natrinema pellirubrum (Type species)

- Natrinema salaciae

- Natrinema versiforme

- Natronoarchaeum [Nac.]

- Natronoarchaeum mannanilyticum (Type species)

- Natronoarchaeum philippinense

- Natronoarchaeum rubrum

- Natronobacterium [Nbt.]

- Natronobacterium gregoryi (Type species)

- Natronobacterium texcoconense

- Natronococcus [Ncc.]

- Natronococcus amylolyticus

- Natronococcus jeotgali

- Natronococcus occultus (Type species)

- Natronococcus roseus

- Natronolimnobius [Nln.]

- Natronolimnobius baerhuensis (Type species)

- Natronolimnobius innermongolicus

- Natronomonas [Nmn.]

- Natronomonas gomsonensis

- Natronomonas moolapensis

- Natronomonas pharaonis (Type species)

- Natronorubrum [Nrr.]

- Natronorubrum aibiense

- Natronorubrum bangense (Type species)

- Natronorubrum sediminis

- Natronorubrum sulfidifaciens

- Natronorubrum texcoconense

- Natronorubrum tibetense

- Salarchaeum [Sar.]

- Salarchaeum japonicum (Type species)

- Salinarchaeum [Saa.]

- Salinarchaeum laminariae (Type species)

- Salinigranum [Sgn.]

- Salinigranum rubrum (Type species)

- Salinirubrum [Srr.]

- Salinirubrum litoreum (Type species)

- Haladaptatus [Hap.]

- Halobacteriaceae

- Halobacteriales

non-valid

- "Halorubrum sfaxense"

- "Candidatus Halobonum tyrrellensis[3]。

- "Candidatus Haloectosymbiotes riaformosensis"[4]。

- "Halopiger djelfamassiliensis sp"[5]。

- "Halopiger goleamassiliensis"[6]。

- "Haloferax namakaokahaiae"'[7]。

- "Halorubrum tropicale"[8]。

- "Haloarcula rubripromontorii"[9]。

- "Halobacterium hubeiense"[10]。

Classification of Gupta et al.[11][12]

Halobacteriales

- Halobacteriaceae (Type genera: Halobacterium)

Haladaptatus, Halalkalicoccus, Haloarchaeobius, Halarchaeum, Halobacterium, Halocalculus, Halorubellus, Halorussus, "Halosiccatus", Halovenus, Natronoarchaeum, Natronomonas, Salarchaeum.

- Haloarculaceae (Type genera: Haloarcula)

Halapricum, Haloarcula, Halomicroarcula, Halomicrobium, Halorientalis, Halorhabdus, Halosimplex.

- Halococcaceae (Type genera: Halococcus)

Halococcus.

Haloferacales

- Haloferacaceae (Type genera: Haloferax)

Halabellus, Haloferax, Halogeometricum, (Halogranum), Halopelagius, Haloplanus, Haloquadratum, Halosarcina.

- Halorubraceae (Type genera: Halorubrum)

Halobaculum, (Halogranum), Halohasta, Halolamina, Halonotius, Halopenitus, Halorubrum, Salinigranum.

Natrialbales

- Natrialbaceae (Type genera: Natrialba)

Halobiforma, Halopiger, Halostagnicola, Haloterrigena, Halovarius, Halovivax, Natrialba, Natribaculum, Natronobacterium, Natronococcus, Natronolimnobius, Natronorubrum, Salinarchaeum.

Living environment

Haloarchaea require salt concentrations in excess of 2 M (or about 10%) to grow, and optimal growth usually occurs at much higher concentrations, typically 20–25%. However, Haloarchaea can grow up to saturation (about 37% salts).

Haloarchaea are found mainly in hypersaline lakes and solar salterns. Their high densities in the water often lead to pink or red colourations of the water (the cells possessing high levels of carotenoid pigments, presumably for UV protection).[13]

Phototrophy in haloarchaea

Bacteriorhodopsin is used to absorb light, which provides energy to transport protons (H+) across the cellular membrane. The concentration gradient generated from this process can then be used to synthesize ATP. Many haloarchaea also possess related pigments, including halorhodopsin, which pumps chloride ions in the cell in response to photons, creating a voltage gradient and assisting in the production of energy from light. The process is unrelated to other forms of photosynthesis involving electron transport however, and haloarchaea are incapable of fixing carbon from carbon dioxide.[14]

Cellular shapes

Haloarchaea are often considered pleomorphic, or able to take on a range of shapes—even within the one species. This makes identification by microscopic means difficult, and it is now more common to use gene sequencing techniques for identification instead.

One of the more unusually shaped Haloarchaea is the "Square Haloarchaeon of Walsby." It was classified in 2004 using a very low nutrition solution to allow growth along with a high salt concentration, square in shape and extremely thin (like a postage stamp). This shape is probably only permitted by the high osmolarity of the water, permitting cell shapes that would be difficult, if not impossible, under other conditions.

Haloarchaea as Exophiles

Haloarchaea have been proposed as a kind of life that could live on Mars; since the Martian atmosphere has a pressure below the triple point of water, freshwater species would have no habitat on the Martian surface.[15]

See also

References

- ↑ See the NCBI webpage on Halobacteria. Data extracted from the "NCBI taxonomy resources". National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 2007-03-19.

- ↑ Minegishi, H., Echigo, A., Shimane, Y., Kamekura, M., Tanasupawat, S., Visessanguan, W., Usami, R. (2012) "Halobacterium piscisalsi Yachai et al. 2008 is later heterotypic synonym of Halobacterium salinarum Elazari-Volcani 1957." Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 62: 2160-2162

- ↑ Ugalde JA, Narasingarao P, Kuo S, Podell S, Allen EE. (2013) Draft Genome Sequence of "Candidatus Halobonum tyrrellensis" Strain G22, Isolated from the Hypersaline Waters of Lake Tyrrell, Australia. Genome Announc. 12;1(6).

- ↑ Filker S, Kaiser M, Rosselló-Móra R, Dunthorn M, Lax G, Stoeck T. (2014) "Candidatu Haloectosymbiotes riaformosensis" (Halobacteriaceae), an archaeal ectosymbiont of the hypersaline ciliate Platynematum salinarum. Syst Appl Microbiol. 37(4):244-251.

- ↑ Hassani II, Robert C, Michelle C, Raoult D, Hacène H, Desnues C. (2013) Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Halopiger djelfamassiliensis sp. nov.Stand Genomic Sci. 9(1):160-174.

- ↑ Ikram HI, Catherine R, Caroline M, Didier R, Hocine H, Christelle D. (2014) Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Halopiger goleamassiliensis sp. nov.Stand Genomic Sci. 9(3):956-959.

- ↑ McDuff S, King GM, Neupane S, Myers MR. (2016) Isolation and characterization of extremely halophilic CO-oxidizing Euryarchaeota from hypersaline cinders, sediments and soils, and description of a novel CO oxidizer, Haloferax namakaokahaiae Mke2.3T, sp. nov.FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 92(4).

- ↑ Sánchez-Nieves R, Facciotti MT, Saavedra-Collado S, Dávila-Santiago L, Rodríguez-Carrero R, Montalvo-Rodríguez R. (2016) Draft genome sequence of Halorubrum tropicale strain V5, a novel halophilic archaeon isolated from the solar salterns of Cabo Rojo, Puerto Rico. Genom Data. 6;7:284-286.

- ↑ Sánchez-Nieves R, Facciotti MT, Saavedra-Collado S, Dávila-Santiago L, Rodríguez-Carrero R, Montalvo-Rodríguez R. (2016) Draft genome of Haloarcula rubripromontorii strain SL3, a novel halophilic archaeon isolated from the solar salterns of Cabo Rojo, Puerto Rico. Genom Data. 6;7:287-289.

- ↑ Jaakkola ST, Pfeiffer F, Ravantti JJ, Guo Q, Liu Y, Chen X, Ma H, Yang C, Oksanen HM, Bamford DH.(2016) The complete genome of a viable archaeum isolated from 123-million-year-old rock salt. Environ Microbiol. 18(2):565-579.

- ↑ Gupta, R.S., Naushad, S., Baker, S. (2015) CPhylogenomic analyses and molecular signatures for the class Halobacteria and its two major clades: a proposal for division of the class Halobacteria into an emended order Halobacteriales and two new orders, Haloferacales ord. nov. and Natrialbales ord. nov., containing the novel families Haloferacaceae fam. nov. and Natrialbaceae fam. nov.." Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 65: 1050-1069

- ↑ Gupta RS, Naushad S, Fabros R, Adeolu M. (2016) "A phylogenomic reappraisal of family-level divisions within the class Halobacteria: proposal to divide the order Halobacteriales into the families Halobacteriaceae, Haloarculaceae fam. nov., and Halococcaceae fam. nov., and the order Haloferacales into the families, Haloferacaceae and Halorubraceae fam nov." Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2016 Feb 2. [Epub ahead of print]

- ↑ DasSarma, Shiladitya (2007). "Extreme Microbes". American Scientist. 95 (3): 224–231. doi:10.1511/2007.65.1024. ISSN 0003-0996.

- ↑ This paragraph taken directly from the Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias page on Halobacterium

- ↑ DasSarma, Shiladitya. "Extreme Halophiles Are Models for Astrobiology" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-02-02. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

Further reading

Scientific journals

- Soppa J (March 2006). "From genomes to function: haloarchaea as model organisms". Microbiology (Reading, Engl.). 152 (Pt 3): 585–90. doi:10.1099/mic.0.28504-0. PMID 16514139.

- Cavalier-Smith, T (2002). "The neomuran origin of archaebacteria, the negibacterial root of the universal tree and bacterial megaclassification". Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52 (Pt 1): 7–76. doi:10.1099/00207713-52-1-7. PMID 11837318.

- Woese, CR; Kandler O; Wheelis ML (1990). "Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 87 (12): 4576–4579. Bibcode:1990PNAS...87.4576W. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. PMC 54159

. PMID 2112744.

. PMID 2112744. - Cavalier-Smith, T (1986). "The kingdoms of organisms". Nature. 324 (6096): 416–417. Bibcode:1986Natur.324..416C. doi:10.1038/324416a0. PMID 2431320.

Scientific books

- Grant WD, Kamekura M, McGenity TJ, Ventosa A (2001). "Class III. Halobacteria class. nov.". In DR Boone, RW Castenholz. Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology Volume 1: The Archaea and the deeply branching and phototrophic Bacteria (2nd ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-387-98771-2.

- Garrity GM, Holt JG (2001). "Phylum AII. Euryarchaeota phy. nov.". In DR Boone, RW Castenholz. Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology Volume 1: The Archaea and the deeply branching and phototrophic Bacteria (2nd ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-387-98771-2.

Scientific databases

- PubMed references for Halobacteria

- PubMed Central references for Halobacteria

- Google Scholar references for Halobacteria

External links

- NCBI taxonomy page for Halobacteria

- Search Tree of Life taxonomy pages for Halobacteria

- Search Species2000 page for Halobacteria

- MicrobeWiki page for Halobacteria

- LPSN page for Halobacteria

- An educational website on haloarchaea

- HaloArchaea.com

- Mike Dyall-Smith's Homepage