Hall Caine

| Sir Hall Caine | |

|---|---|

|

From a portrait by R E Morrison | |

| Born |

Thomas Henry Hall Caine 14 May 1853 Runcorn, Cheshire, England |

| Died |

31 August 1931 (aged 78) Greeba Castle, Isle of Man |

| Resting place | Maughold, Isle of Man |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Nationality | British |

| Period | Victorian, Edwardian |

| Genre | Novels, biography, religion |

| Subject | romance |

| Spouse | Mary Chandler (m. 1886–his death 1931) |

| Children | |

Sir Thomas Henry Hall Caine CH KBE (14 May 1853 – 31 August 1931), usually known as Hall Caine, was a British author. He is best known as a novelist and playwright of the late Victorian and the Edwardian eras. In his time, he was exceedingly popular, and, at the peak of his success, his novels outsold those of his contemporaries. Many of his novels were also made into films. His novels were primarily romances, involving love triangles, but also addressed some of the more serious political and social issues of the day.

Caine acted as secretary to Dante Gabriel Rossetti and at one time he aspired to become a man of letters. To this end he published a number of serious works, but these had little success. He was a lover of the Isle of Man and Manx culture, and purchased a large house, Greeba Castle, on the Island.

For a time he was a Member of the House of Keys, but he declined to become more deeply involved in Manx politics. A man of striking appearance, he travelled widely and used his travels to provide the settings for some of his novels to good effect. He came into contact with, and was influenced by, many of the leading personalities of the day, particularly those of a socialist leaning.

Caine's novels are considered outdated by creators of English literature curricula today, and despite his immense popularity during his life, he is now virtually unknown or forgotten. However, some of his more popular novels have been published as paperbacks in recent years, predominantly for the Manx market catering for tourists to the Isle of Man.

Early life and influences

Early days

Thomas Henry Hall Caine was born on 14 May 1853 at 29 Bridgewater Street, Runcorn, Cheshire, England,[1][nb 1] the eldest of six children of John Caine (1825-1904) and his wife Sarah Caine (née Hall, (1828-1912)). Sarah was born in Whitehaven, Cumbria, and descended from an old Quaker family of Ralph Halls, china manufacturer.[2] After living for many years in Cumbria the Hall family moved to Liverpool where Sarah, a seamstress, met and married John. As her husband was a member of the Anglican Church and not a Quaker she lost her connection with the Society of Friends. Throughout her life she retained the Quaker simplicity of life and dress.[3] John Caine, a blacksmith, came from the Isle of Man. In the absence of work he emigrated to Liverpool, where he trained as a shipsmith. At the time of Caine's birth, he was working temporarily in Runcorn docks. Within a few months the family were back in Liverpool, where Caine spent his childhood and youth. They rented rooms at 14 Rhyl Street, Toxteth, convenient for Liverpool Docks and within a small Manx expat community. By 1858 they had moved to number 21. Early in 1862 they moved to 5 Brougham Street.[4]

During his childhood Caine was occasionally sent to stay with his grandmother, Isabella, and uncle, William, a butcher-farmer, in their thatched cottage at Ballaugh on the Isle of Man.[5][6] His grandmother nicknamed him 'Hommy-Beg', Manx for 'Little Tommy'.[7] The island has a long history of folklore and superstition, passed from generation to generation.[8] Continuing this tradition Grandmother Caine passed on her knowledge of local myths and legends to her grandson, telling him countless stories of fairies, witches, witch-doctors and the evil eye while they were sat by the fire.[9]

When Caine was nine he lost two of his young sisters within a year. Five year old Sarah developed hydrocephaly after a fever. Fourteen month old Emma died in convulsions brought on by whooping cough she caught from him and his brother John. Caine was to be sent to the Isle of Man to recover from his illness and grief. He was put on a boat to Ramsey by his father, with a label pinned on his coat and assurances that his uncle would meet him. A fierce storm occurred preventing the ferry from reaching land. Caine was rescued by a large rowing boat. He would later draw on this experience when writing the scene in The Bondman in which Stephen Orry is cast ashore there.[10]

The Caine family belonged to the Baptist Church in Myrtle Street, Liverpool, presided over by the charismatic Hugh Stowell Brown, a Manxman and brother of poet Thomas Edward Brown. Brown's public lectures and work among the poor made him a household name in Liverpool. Caine participated in the literary and debating society Brown had established. While Caine was very young he became well known and highly regarded by the people of south Liverpool. There he was in great demand as a speaker, having the ability to engage an audience from his first word.[11] Through studying the works of the Lake School of Poets, and the best writers of the eighteenth century, he combined this knowledge with his own ideas of perfection, and went on to develop his level of eloquence to oratory.[12]

From the age of ten Caine was educated at the public school in Hope Street, Liverpool, becoming head boy in his last year there.[13] He spent many hours on his own avidly reading books, notably at Liverpool's Free Library.[14] Caine also experienced what he described as the ‘scribbling itch’ for writing. He produced essays, poems, novels and overview histories with little thought of them being published.[15]

In common with all 19th century towns Liverpool was unsanitary. In 1832 there had been a cholera epidemic. As panic and fear of this new and misunderstood disease spread, eight major riots had broken out on the streets along with several smaller uprisings.[16] In 1849 a second epidemic occurred.[17] When Caine was thirteen the third outbreak of cholera occurred in July 1866.[18] Memories of that time were to stay with him, the deaths, the large volume of funerals and prayer meetings in open spaces that were happening all around him.[19]

Apprentice and schoolmaster

At fifteen, after leaving school, he was apprenticed to John Murray, an architect and surveyor.[20] Murray was a distant relative of William Ewart Gladstone.[21] On 10 December 1868, the day of the general election when Gladstone was to be elected as Prime Minister, Caine was running to offices in Union Court, belonging to Gladstone’s brother, with telegrams announcing the results of the contests all over the country. Caine was breaking the news of great majorities before Gladstone had time to open his telegrams.[22] Caine was to meet Gladstone on another occasion when he was on Gladstone’s estate at Seaforth, Merseyside. The surveyor-in-chief had not appeared one morning and a fifteen year old Caine took his place.[23] Caine had left a lasting impression on Gladstone, as two years later Caine had a letter from Gladstone’s brother saying the Prime Minister wished to appoint him steward of the Lancashire Gladstone estates. Caine declined the offer.[24]

Caine’s maternal grandparents had lived with the rest of his family while they were growing up in Liverpool. His grandfather, Ralph Hall, died in January 1870, when Caine was seventeen. In the same year of his life Caine was reunited with William Tirebuck, a friend from his school days, when the business of their masters brought them together. United in their interest in literature, they made a juvenile attempt to establish a monthly manuscript magazine, assisted by Tirebuck’s sister. Tirebuck was editor, printer, publisher and postman; Caine was principal author. One of the magazine’s contributors inherited a small fortune which he invested. About ten thousand copies were printed, followed by a delayed issue no.2. After this venture Tirebuck returned to his position as junior clerk in a merchant’s office.[25][26]

Suffering from what he would describe as “the first hint of one of the nervous attacks which even then beset me”, and later as “the first serious manifestation of the nervous attacks which have pursued me through my life",[27] Caine quit his job with Murray and, arriving unannounced, went to live with his uncle and aunt, James and Catherine Teare in Maughold on the Isle of Man.

Teare was the local schoolmaster, and as Caine was to learn, ill with tuberculosis. Caine became his assistant teaching in the schoolhouse. Finding their accommodation in part of the schoolhouse was crowded Caine camped in a nearby tholtan, a half-ruined cottage. Using his stonemason skills, taught to him by his grandfather Hall, he restored and lived in the cottage. On the stone lintel above the door he carved the name Phoenix Cottage and the date 8 January 1871.[28][29]

Encouraged by Teare, after he had written to reassure Caine’s parents that he might one day be able to make a living as a writer, Caine wrote anonymous articles for a local newspaper on a wide range of religious and economic questions.[30]

John Ruskin had started his Guild of St George and began expressing his ideas in his new monthly series, Fors Clavigera, written as a result of his feelings regarding the acute poverty and misery in Great Britain at the time. Rumours of undergraduates, following Ruskin’s ideas, digging the ground outside Oxford, reached Caine. He was inspired by Ruskin to begin writing denunciations of the social system and of the accepted interpretation of the Christian faith.[31] Caine was to become 'an eager pupil and admirer' of Ruskin.[32] He later became a frequent visitor to Ruskin's Coniston home, Brantwood.

Following the death of James Teare in December 1871, Caine carved a headstone for the grave. After officially taking his place as schoolmaster, he also performed the extra unpaid services his uncle had provided, “such as the making of wills for farmers round about, the drafting of agreement and leases, the writing of messages to banks protesting against crushing interest, and occasionally the inditing of love letters for young farm hands to their girls in service on farms that were far away”. Later he would draw on this material to use in his writing.[33] In March 1872, he had a letter from Murray his master, the architect, which said “Why are you wasting your life over there? Come back to your proper work at once.” Caine was on his way back to Liverpool within a week.[34][35]

Journalist and theatre critic

In April 1872, at the age of eighteen, Caine was back home in Liverpool where he set about applying his knowledge, gained working in the drawing office, into articles on architectural subjects, and subsequently published in the Builder and Building News. These were Caine’s first works published for a national audience. The articles caught Ruskin’s attention and he wrote words of encouragement to Caine.[36]

Seeking to be published, he offered his services, without payment, as a theatre critic to a number of Liverpool newspapers, which were accepted. He used the pseudonym ‘Julian’.[37] Before Henry Irving played Hamlet, his intention to play the part differently to any other actor was known to Caine and he contributed many articles on the subject to various papers.[38] The study of Shakespeare and the Bible from his earliest years were his ‘chief mental food’.[39] As he had become more absorbed by literary studies he was not content with reading Shakespeare’s plays, so he was reading all of the most notable playwrights of the Elizabethan age and “he began to make acquaintance with the dramatists’.[40]

He wrote his first extended work of fiction, a play, but could not afford to have it produced.

“Partly from the failure of faith in myself as a draughtsman and partly from a desire to be moving on”[41] Caine left his employment with Murray and joined the building firm of Bromley & Son as a draughtsman.

Together with William Tirebuck and George Rose, his friends from school days,[42] Caine applied himself to establishing Liverpool branches of the Shakespeare Society, and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings.[43] They called their own organisation Notes and Queries Society and held their meetings at the prominent Royal Institution, Colquitt Street. Caine was president of the society and their meetings were reported in the Liverpool newspapers.[44] The ‘Notes’ were often provided by John Ruskin, William Morris and Dante Gabriel Rossetti.[45]

On 16 October 1874 Henry Irving wrote to Caine agreeing to his request to use his portrait in Stray Leaves a new monthly magazine he was launching.[46][47] In his capacity as critic of the Liverpool Town Crier, Caine attended the first night of Hamlet at the Lyceum Theatre, London, on 31 October 1874, with Irving in the title role. Caine was enthralled by Irving’s performance and after his enthusiastic review was published in the newspaper, he was asked to reprint it as a broad-sheet pamphlet, as it was of such a high quality.[48]

Caine’s long narrative poem, Geraldine, appeared in print in March 1876. It was a completion of Coleridge's unfinished poem Christabel.[49][50]

The Caine family had moved into a larger house in 1873, at 59 South Chester Street, Toxteth, where Caine shared a bedroom with his younger brother John, a shipping clerk.[51] John contracted tuberculosis which he passed to his brother. By 1875 Caine had permanent lodgings in New Brighton, spending weekends there “for the sake of his health”.[52] Caine became increasingly unwell from the beginning of January 1877. In April the same year John, died from tuberculosis, aged 21. Dangerously ill, Caine was terrified of suffering the same fate.[53] He recovered, but the disease left him with permanent lung damage, and throughout his life he had attacks of bronchitis. In his 1913 novel The Woman Thou Gavest Me, he describes Mary O’Neil dying of tuberculosis.[54]

Manchester Corporation had covertly been buying land for building the proposed Thirlmere Aqueduct, intended to supply water to the city. When discovered, it outraged the local community. Thirlmere, close to the centre of the Lake District, in an area, not only celebrated in the poetry of early conservationist William Wordsworth and fellow Lake poets, but also used as a summer residence by writers, amongst others.[55] In opposition to damming the lake at Thirlmere to form a reservoir, the first environmental group, Thirlmere Defence Association was formed in 1877.[56] It was supported by the national press, Wordsworth’s son and John Ruskin. Caine, incensed at what he perceived as a threat to his beloved Cumbria, joined the movement, initiating a Parliamentary petition.[57] Thirlmere was to be the setting for his novel The Shadow of a Crime.[58]

In response to his lecture The Supernatural in Shakespeare,[59] given in July 1878, in a meeting chaired by Professor Edward Dowden, Matthew Arnold wrote him a long letter of praise. He was also praised by Keats’s biographer, Lord Houghton.[60]The lecture appeared in Colburn’s New Monthly Magazine in August 1879,[61]

Irving presided at a meeting of the Liverpool Notes and Queries Society in September 1878. At Irving’s invitation, he travelled to London to attend Irving's first night at the Lyceum Theatre under his own management, presenting his new production of Hamlet with Ellen Terry as Ophelia on 30 December. It was at this time that Caine was introduced to Irving’s business manager, Bram Stoker, who was to become one of his closest friends.[62] Stoker was subsequently to dedicate his famous novel Dracula to Caine, under the nickname 'Hommy-Beg'.

In 1879 Caine edited a booklet of the papers presented to the Notes and Queries Society by William Morris, Samuel Huggins and John J. Stevenson on the progress of public and professional thought on the treatment of ancient buildings which was described as “‘well worth reading”.[63][64] At the 1879 Social Science Congress held in Manchester Town Hall, Caine read his paper A New Phase of the Question of Architectural Restoration. He spoke of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, its purpose, actions and achievements.[65] Caine had joined the society the previous year and remained a member for the rest of his life. One of the society's founders was William Morris.

Friendship with Francis Tumblety

As a young man of 21 Caine encountered the self-proclaimed ‘Great American Doctor’, Francis Tumblety, aged 43, after he set up at 177 Duke Street, Liverpool, offering herbal cure-all elixirs and Patent medicines to the public, which he claimed were secrets of the American Indians. Tumblety posed at various times in his life as a surgeon, an officer in the federal army, and a gentleman.[66] He always followed his name with “M.D.” and used the title ‘Doctor’, without the supporting qualifications for which he was fined in Saint John, New Brunswick in 1860.[67]

From September 1874, Tumblety was announcing his arrival in Liverpool by advertising in local newspapers, later including testimonials.[68] Following the death of Edward Hanratty in January 1875, the same night he took a spoon of medicine supplied by Tumblety, and action taken by William Carroll to sue Tumblety for £200 after allegedly publishing a false testimonial, Tumblety fled to London.[69] Many newspapers reported the stories and in the wake of this adverse publicity, Tumblety recruited Caine to edit his biography. Late January Tumblety wrote requesting Caine to obtain a quote for printing ten thousand copies in Liverpool, telling of being betrayed by a supposed friend, and praising Caine for his genuine friendship.[70][71] After Caine forwarded his letters, he wrote February 1 discussing the upcoming biography and enclosed a letter supposedly originating from the Isle of Wight, by Napoleon III.[72] The following day the first advert for the upcoming pamphlet appeared in the Liverpool Mercury.[73] Tumblety changed lodgings, initially missing an urgent telegram from Caine indicating there was a problem with the publication. His response was to tell Caine to stop until he saw the proofs. Tumblety offered to pay for Caine to visit him in London to discuss the pamphlet, his letter dated February 16 indicating Caine had taken up the offer.[74] He told a friend that his visit to Tumblety was “arduous”.[75] A spate of correspondence relating to the publication ensued, Tumblety supplying Caine with names of notable people to be included in the pamphlet, along with money for printing and advertising. Tumblety later wrote of disputes with the printer. Claiming to be too ill to send money, he sent Caine a printer’s bill for payment. Tumblety had hired an assistant who read the proofs to him. The pamphlet entitled Passages from the Life of Dr Francis Tumblety, and the fourth of Tumblety’s biographies, was published March 1875.[76]

Tumblety wrote to Caine in April 1875 that he was contemplating manufacturing his pills in London, and required a partner to share the profits, telling Caine to approach Liverpool chemists as proposed outlets.[77] Caine had declined a further invitation to London, but Tumblety persisted with his invites to join him in London, later made by telegram, additionally inviting him on a planned trip to America.[78] Around the time Alfred Thomas Heap was hanged in Kirkdale Gaol, Liverpool, for an abortion-related death, Tumblety, who had been arrested in 1857 for selling abortion drugs, disappeared. Caine made enquiries as to his whereabouts.[79][80] Briefly Tumblety set up offices in Union Passage, Birmingham. His correspondence turned menacing, demanding money from Caine.[81] Tumblety left London for New York City in August 1876. Failing to entice Caine to join him, he followed months later with a pleading letter from San Francisco, after which there is no record of any further contact.[82][83]

Rossetti years

Caine delivered a series of three lectures on Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s work and the Pre-Raphaelite movement between November 1878 and March 1879, afterwards combining them into an essay which was printed in Colburn’s New Monthly Magazine.[84] Caine sent a copy of the magazine to the poet Rossetti, who by that time had become a virtual recluse and was "ravaged by years of addiction to chloral and too much whisky".[85] Rossetti wrote his first letter to Caine 29 July 1879. This letter was the first of nearly two hundred in quick succession.[86] Around this time Caine’s father was badly injured in an accident at work and Caine took responsibility for supporting his parents and siblings.[87] Early in 1880 he wrote Stones crying Out, a short book on the restoration of old buildings. Two of the chapters were papers he had read at the Social Science Congress and Liverpool Library.[88] Rossetti introduced Caine to Ford Madox Brown, who was at the time working on The Manchester Murals. Following his visit to write an article on Brown's frescoes in July 1880 they became friends. On a later visit Caine accepted Brown’s invitation to sit for one of the figures while he was working on The Expulsion of the Danes from Manchester, the third fresco.[89] Caine and Rossetti eventually met in September 1880 when Caine visited Rossetti in his home 16 Cheyne Walk, Chelsea, London, where he lived "in shabby splendour".[90]

The strain of overworking was affecting Caine's health and in 1881, deciding to focus on his literary career, he left his job at Bromley & Son and went to St John's in the Vale, Cumbria.[91] Before long Rossetti wrote that he too was ill and asked Caine to go to London planning to return to Cumbria with him. By the time Caine arrived in London Rossetti had changed his mind and instead Caine became Rossetti’s housemate.[92] Early in September, persuaded by friends and family Rossetti spent a month with Caine at St John's in the Vale, accompanied by Fanny Cornforth.[93] Whilst there, Caine recited a local myth to Rossetti. The myth was to become the inspiration for his first novel The Shadow of a Crime.[94] He was also delivering weekly lectures in Liverpool.[95]

Caine negotiated the acquisition of Rossetti's largest painting Dante's Dream of the Death of Beatrice by Liverpool's Walker Art Gallery,[96][97] representing the painter at its installation in November 1881.[98]In January 1882 Caine's anthology Sonnets of Three Centuries was published.

After Rossetti “had an attack of paralysis on one side”, his medical adviser Mr John Marshall recommended a change of air.[99] Architect John Seddon offered Rossetti the use of Westcliffe Bungalow at Birchington, Kent. [100] Caine eventually persuaded Rossetti to make the trip to Birchington and they both arrived on February 4 1882, accompanied by Caine's sister and Rossetti’s nurse. Caine stayed with Rossetti’s until his death on Easter Sunday, 1882.[101][102]

The writer

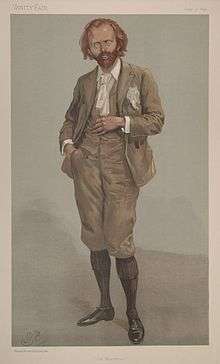

Caine as caricatured in Vanity Fair, July 1896

After Rossetti's death, Caine gained an income by writing articles for the Liverpool Mercury, while at the same time preparing a book about his time with Rossetti. This was entitled Recollections of Dante Gabriel Rossetti; it appeared in October 1882 and sold reasonably well. In 1883 Cobwebs of Criticism was published, a book about reviewers and whether or not their criticisms had been valid. During this time he was maintaining old friendships and building new ones with people who included Ford Madox Brown, Algernon Charles Swinburne, Theodore Watts, R. D. Blackmore, Matthew Arnold, Robert Browning and Christina Rossetti. In consequence of his work as a theatre critic, Caine met the actor-manager Wilson Barrett.

It was at this time that Caine began to consider that his future might lie in writing fiction.[103] After appearing as a serial in the Mercury, Caine's first novel Shadow of a Crime was published by Chatto & Windus in February 1885. Set in the Lake District and based on a love triangle, it sold well and was still in print in the 1900s. It "launched Caine on a career as a romantic novelist of huge popularity which was to span forty years and produce fifteen novels".[104] The same year She's All The World To Me, another love triangle, was published in New York, a book which Watts and Chatto considered was not up to his previous standard — but Caine wanted the money from it, and also exposure in America.[105] The following year Chatto and Windus published A Son of Hagar in three volumes. Again set in the Lake District, it dealt with the theme of illegitimacy. It received some good reviews, but not from George Bernard Shaw who "took a bilious view of the romantic novels of his day with their ridiculous plots". However, in time Shaw and Caine were to become good friends.[106]

Caine craved to be recognised as a man of letters,[107] and to this end he wrote a biography, Life of Coleridge, which was published in 1887. It was a failure, and this confirmed to Caine that his future lay in fiction. Later that year his next novel The Deemster was published, again by Chatto & Windus. It was the first of Caine's novels to be set in the Isle of Man, where judges are called deemsters. It was set in the 18th century, and included the story of a fatal fight, with the body being taken out to sea only to float back to land the next day. It was a big success and the reviews were excellent. It ran to more than 50 editions and was translated into at least 9 languages. Wilson Barrett bought the stage rights and produced a stage version called Ben-my-Chree (Manx for 'Girl of my Heart') which was also successful, despite its changed ending.

In January 1890, the next novel was published after being serialised in the Isle of Man Times. This was The Bondman which was published by Heinemann rather than Chatto & Windus, because they offered better terms. It is set in the Isle of Man and in Iceland. Again it was a great success, despite its complicated story and its being "hopelessly sentimental and melodramatic".[108] Later the same year, in September, the next novel, The Scapegoat, was published. This time the novel was set in Morocco and its main theme is the persecution of the Jews; Caine hated anti-Semitism. It had a pro-Jewish theme and although it was a critical success, it did not sell as well as The Bondman. The Scapegoat brought Caine a considerable correspondence, mainly because of its pro-Jewish stance.[109]

Following this, Caine returned to non-fiction, publishing three lectures on the history of the Isle of Man as a book entitled The Little Manx Nation. His next fiction consisted of three novellas in one volume which were entitled Cap'n Davey's Honeymoon, The Last Confession, and The Blind Mother. This book was published in 1893 and was dedicated to Bram Stoker, but did not sell well. However, his next book, The Manxman, published in 1894, was one of his greatest successes, eventually selling over half a million copies and being translated into 12 languages. This was again set in the Isle of Man and involved a love triangle.

During his career Caine travelled widely, and used his experiences abroad in his writings. Places visited included Iceland, Morocco, Egypt, Palestine, Rome, Berlin, Austria, and the Russian frontier. For many years Caine had been concerned about matters relating to copyright, and in 1895 he travelled via the United States of America to Canada for the Society of Authors and successfully negotiated for the introduction of copyright protection there.

In 1897 came the most successful novel yet, The Christian. It was the first novel in Britain to sell over a million copies[110] although once again it attracted much adverse publicity. As with most of his novels, it was first published in serial form, this time in the Windsor Magazine and then, dramatised by the author, produced as a play. The theme of the novel was the problems encountered by a young woman trying to live an independent life; it was the first time that Caine had taken up the Woman Question. The play was first performed at the Knickerbocker Theatre in New York in October 1898, and it was also a great success. Caine followed it by a lucrative lecture tour. However, when The Christian was first produced in England at the Duke of York's Theatre in October 1899, its reception was only lukewarm.[111]

It was to be four years before the appearance of Caine's next work, The Eternal City. This was set in Rome and was the only novel to be first conceived as a play.[112] It appeared in serial form in The Lady's Magazine and finally in book form in August 1901. This proved to be Caine's most successful novel; it sold more than a million copies in English alone, and appeared in 13 other languages. It was another romance, with the hero being accused of plotting to murder the Italian king. The stage version opened at His Majesty's Theatre, London in October 1902. Once again the reviews were mixed, the literary critics tending to be scathing, while it was praised by many clergymen.[113] Around this time, Caine tried to revive the literary magazine Household Words which had been founded by Charles Dickens.

In August 1902 King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra visited the Isle of Man. The Queen had enjoyed Caine's Manx novels and Caine was invited to join the royal couple on their yacht and to accompany them on their tour of the island the following day. The Eternal City opened as a play in October with incidental music by Mascagni. A few days after the London opening the Caines went to USA for the play's American opening in Washington, which was followed by a tour. In 1902 all of Caine's novels were still in print and towards the end of 1903 six companies were performing The Eternal City, in England, USA, Australia and South Africa. However, that year Household Words ceased publication.

The Prodigal Son was published in November 1904, again by Heinemann, and in the same month it opened as a play at the Grand Theatre, Douglas. It was set mainly in Iceland, with scenes in London and the French Riviera, and is again based on the eternal triangle. The book was again an instant success and once again the criticisms were mixed; it was translated into 13 languages. The play opened in September 1905 at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane with Caine's sister, Lily, playing a main part but it had only a moderate run. In 1906 The Bondman appeared for the first time as a play, produced again at Drury Lane, with Caine's son Derwent aged 16, making a stage début. The setting had been changed from Iceland to Sicily, which gave an opportunity for an eruption of Mount Etna in the last act. Mrs Patrick Campbell took a leading role. Once again while the play was a huge popular success, it was panned by the critics. 1908 saw the publication of My Story, an autobiography which said more about others, particularly Rossetti, than about himself, and much of what was written was not entirely correct.[114] It did not sell particularly well.

Caine's next major work of fiction was The White Prophet which was set in Egypt and which addressed the problems of colonial rule and attempted a synthesis of the world's religions. It appeared first in its stage version in Douglas in August 1908. On the first night one of the actors was ill and Caine himself took his part. It appeared as a book the following month. For the first time in a Caine novel, the strongest element was not romance, but rather adventure, with a degree of theological discussion. The book did not do as well as his previous ones.

The next major work was The Woman Thou Gavest Me, published in 1913, which "caused the biggest furore of any of his novels".[115] Libraries objected to its morals, dealing as it did with the divorce laws of the time and attitudes towards illegitimacy. Once again it addressed the Woman Question. However, it sold extremely well. It was reprinted five times before the end of the year when nearly half a million copies had been sold. Despite the storm of criticism, or maybe because of it, Caine's reputation as a novelist had been restored.

The Great War

In previous years Caine had edited books to raise money for Queen Alexandra's charities in 1905 and 1908. In 1914, following the outbreak of the Great War, he decided to produce another charity book, this time in support of the exiled King Albert of Belgium.[116] King Albert rewarded him by creating him an Officer of the Order of Leopold of Belgium.

Caine tried to involve America in the war by writing articles, mainly for The New York Times and in 1915 he gave a series of lectures in the USA but these were not well received. He wrote a series of articles for The Daily Telegraph about how the war was affecting "ordinary" people. These were published in 1915 as a book entitled The Drama of 365 Days: Scenes in the Great War. In 1916 he was invited to work with Lord Robert Cecil at the Foreign Office towards the creation of the League of Nations after the end of the war. The same year Caine produced a small book entitled Our Girls: Their Work for the War Effort to show that women were also playing an active part in the war. He was also involved in writing a propaganda film to assist the war effort but the war ended before the film could be completed.

Towards the end of 1917 Caine was offered a baronetcy but he declined it and instead he accepted a knighthood as a KBE, insisting on being called, not 'Sir Thomas Hall Caine' but 'Sir Hall Caine'.

After the war

Caine returned to writing novels and in 1921 Heinmann's published The Master of Man: The Story of a Sin. It was set in the Isle of Man and involves infanticide. Initially it sold well but sales soon dropped. It was considered to be old-fashioned; Caine was using old themes and had not kept up with the time. One reviewer referred to Caine as "this Victorian author".[117] The following year Caine acquired the Sunday Illustrated newspaper which had been founded by Horatio Bottomley. In October of that year he was made a Companion of Honour. Caine's last novel The Woman of Knockaloe was brought out in 1923, this time published by Cassell's. It is another love story set on the Isle of Man but this time dealing with the harm caused by racial hatred. That year he sold the Sunday Illustrated and also made his first broadcast, an address on 'Peace'.

Caine's last published work in his lifetime was a revised version of Recollections of Rossetti with a shortened title to coincide with the centenary of Rossetti's birth in 1928. In 1929 Caine was given the Freedom of Douglas. For much of his life Caine worked on a book entitled Life of Christ but it was not published until some time after his death, in 1938 with a foreword by his two sons. It "aroused little or no interest and quickly disappeared".[118]

Politics

In 1901 Caine was elected a Member of the House of Keys as a Liberal for the constituency of Ramsey at a by-election and was re-elected, with a smaller majority, in 1903. This had been helped by the success of his Manx novels benefiting the tourist trade of the island. He continued as a member until 1908, although due to the other pressures on his time he seldom spoke in the House. He also had little time to offer to politics on a larger scale. When he was invited by Lloyd George to stand for the English parliament he refused. He was, however, elected as the first president of the Manx National Reform League.[119]

Films

Some of Caine's novels were made into films, all of which were black-and-white and silent. Unauthorised versions of The Deemster and The Bondman were made by Fox Film Corporation. In 1914, Vitalograph filmed The Bondman, which was also unauthorised.

The first authorised film of a Caine novel was a version of The Christian, made by the London Film Company in 1915 and starred his son Derwent Hall Caine in one of the parts. In 1916, The Manxman, also produced by the London Film Company, was filmed on the Isle of Man and, when released in 1917, drew huge crowds in Britain and America. In 1918 Caine was recruited by the Prime Minister David Lloyd George to write the screenplay for the propaganda film Victory and Peace (1918). A film of The Deemster, also starring Derwent, was made by the Arrow Film Corporation and released in 1918. The Christian was also remade in 1923, produced by Samuel Goldwyn, and directed by the celebrated Maurice Tourneur.

In 1915, the first version of The Eternal City was produced by Paramount Pictures, and in 1923 the Samuel Goldwyn Company shot a remake in Italy. Caine was so unhappy with the latter film that he tried to withdraw his name from it, unsuccessfully.[120]

More films were in progress, including Darby and Joan. This was based on an old novella, was produced by Master Films, and again starred Derwent. A film of The Woman Thou Gavest Me was made in 1919 by Famous Players and this drew good audiences and good reviews. The Woman of Knockaloe was filmed by Paramount Pictures in 1927 as Barbed Wire. Then Alfred Hitchcock arrived on the Isle of Man to film The Manxman (1929) but he and Caine did not get on well and the rest of the film was shot in Cornwall. The Manxman was Hitchcock's last silent film. Caine was not happy with it.[121]

Personal and domestic

In appearance Caine was a short man who tended to dress in a striking fashion. His eyes were dark brown and slightly protuberant, giving him an intense stare. He had red-gold hair and a dark red beard which he trimmed to appear like the Stratford bust of Shakespeare; indeed if people did not notice the likeness he was inclined to point it out to them.[122] He was also preoccupied throughout his life with the state of his health. This was often the result of overwork or other stresses in his life and he would sometimes use nervous exhaustion as an excuse to escape from his problems.[123]

After Rossetti's death when he was living in rooms in Clement's Inn Caine came into contact with a girl named Mary Chandler. Following pressure from her stepfather, Mary came to live with Caine. She was aged 13 (which was at that time the age of consent) while Caine was aged 29. Their friends assumed they were married.[124] Mary had had little schooling and so Caine arranged for her to have some more education at Sevenoaks where she stayed for six months being taught either at a private school or privately by a governess.[125] She then returned to live with Caine and in 1884, at the age of 14, she was pregnant. Their son, to be named Ralph, was born in their rented house in Hampstead in August 1884. The following month they moved to live in Aberleigh Lodge, Bexleyheath, next door to William Morris' Red House. In 1886 they travelled to Scotland where they were married in Edinburgh under Scottish law by declaration before witnesses. After the publication of Caine's first novel, Mary kept a scrapbook of everything relating to him.[126]

In 1888 after the success of The Deemster, the lease on Aberleigh House was nearing its end and Caine wanted to live in the Lake District. He bought a house called Hawthorns in Keswick and the family moved there while Caine rented part of a flat in Victoria Street, London, leaving Mary to supervise the move. She became a devoted wife, reading all his work, advising and criticising when appropriate and was his first secretary. Later Caine distanced himself from her which "nearly destroyed her".[127]

Their second son, Derwent was born in 1891. Caine felt an urge to move to the Isle of Man and in 1893 they rented a castellated house which looked over the Douglas to Peel road called Greeba Castle for six months. Meanwhile, their London home, which had been in Ashley Gardens, became a flat in Whitehall Court between Whitehall and the Victoria Embankment. They did not return to Greeba Castle at this time but took a house in Peel. Hawthorns, which in the meantime had been occupied by Thomas Telford, was sold. After years of haggling, Caine bought Greeba Castle in 1896. He lived there for the rest of his life and made extensive internal and external alterations to it. However, Mary never liked the house. Following the production of The Christian in New York and the subsequent lecture tour, the marriage began to come under strain but it did survive.

In 1902 the Caines rented a large house on Wimbledon Common, The Hermitage, and Mary spent much time there while Caine was abroad or at Greeba Castle. Rumours spread that the marriage was in trouble and, as many of his visitors were male, that Caine was homosexual. However, there was never any reliable substance to this.[128] By 1906 the couple were leading increasingly separate lives but Mary remained loyal and faithful throughout.[129]

In 1912, Derwent Hall Caine had an illegitimate daughter, Elin, and she was brought up as Caine and Mary's child.[130] By 1914 Mary at last had her own London house — Heath Brow which overlooked Hampstead Heath. After the Great War this house had become too big and Mary moved into Heath End House, again overlooking Hampstead Heath. By 1922 they informally separated; Caine could not live with Mary, nor could he break with her completely.[131] From that time, both suffered from various ailments.

In August 1931 at age 78 Caine slipped into a coma and died. On his death certificate was the diagnosis of "cardiac syncope".[132] He was buried in Kirk Maughold churchyard and a slate obelisk was erected over his grave, designed by Archibald Knox. A memorial service was held in St Martin's-in-the-Fields. In March 1932, six months after her husband's death, Mary Hall Caine died from pneumonia. She was buried alongside her husband. A statue of Hall Caine stands in Douglas, financed by money from the estate of Derwent Hall Caine.

Postscript

Caine's legacy

Hall Caine was an enormously popular and best-selling author in his time. Crowds would gather outside his houses hoping to get a glimpse of him. He was "accorded the adulation reserved now for pop stars and footballers",[133] and yet he is now virtually unknown.

Allen suggests two reasons for this. First that, in comparison with Dickens, his characters are not clearly drawn, they are "frequently fuzzy at the edges" while Dickens' characters are "diamond-clear"; and Caine's characters also tend to be much the same as each other. Something similar could also be said about his plots. Possibly the main drawback is that although Caine's books can be romantic and emotionally moving, they lack humour; they are deadly earnest and serious.[134]

At one time the Isle of Man had a second civil airport near Ramsey which was called the Hall Caine Airport. It closed in 1939.[135]

Critical appraisals

- Despite his proving the wealthiest of Victorian novelists,[136] Caine has been largely dismissed as a mere melodramatist by subsequent criticism.[137]

- G. K. Chesterton said in "A Defence of Penny Dreadfuls" that "it is quite clear that this objection, the objection brought by magistrates, has nothing to do with literary merit. Bad story writing is not a crime. Mr. Hall Caine walks the streets openly, and cannot be put in prison for an anticlimax."[138]

- Thomas Hardy criticised Caine for his excessive egotism.[139]

Bibliography

Prose fiction

- 1885 - The Shadow of a Crime

- 1885 - She's All the World to Me: A Manx Novel

- 1886 - A Son of Hagar

- 1887 - The Deemster

- 1890 - The Bondman: A New Saga

- 1890 - The Scapegoat: A Romance

- 1890 - The Prophet, published as a novella

- 1893 - Cap'n Davey's Honeymoon, The Last Confession, The Blind Mother, 3 novellas published in one volume

- 1894 - The Manxman

- 1897 - The Christian

- 1901 - The Eternal City

- 1904 - The Prodigal Son

- 1906 - Drink: A Love Story on a Great Question

- 1909 - The White Prophet

- 1913 - The Woman Thou Gavest Me

- 1914 - Charlie the Cox: A Life Poem, a short story published as a part of Princess Mary's Gift Book[140]

- 1921 - The Master of Man: The Story of a Sin

- 1923 - The Woman of Knockaloe: A Parable (published in 1927 as Barbed Wire)

Theatre and film scripts

- 1894 - The Madhi: or Love and Race, A Drama in Story

- 1896 - Jan the Icelander or Home, Sweet Home, A Lecture Story

- 1888 - The Prophet, a play which was never staged

- 1889 - The Good Old Times, a play

- 1903 - The Isle of Boy: A Comedy, a play

- 1906 - The Bondman Play

- 1916 - The Prime Minister, a play

- 1916 - The Iron Hand, a one-act play

- 1919 - Darby and Joan, a film script

Non-fiction

- 1879 - "The Supernatural in Shakspere"

- 1880 - "The Supernatural Element in Poetry"

- 1880 - "Politics & Art"

- 1882 - Sonnets of Three Centuries: An Anthology edited by Caine

- 1882 - Recollections of Dante Gabriel Rossetti

- 1883 - Cobwebs of Criticism

- 1887 - Life of Samuel Coleridge Taylor

- 1891 - The Little Manx Nation

- 1894 - The Little Man Island: Scenes and Specimen Days in the Isle of Man, a guide to the island

- 1905 - The Queen's Christmas Carol, an anthology edited by Caine, for the queen's charities

- 1906 - My Story, an autobiography

- 1908 - Queen Alexandra's Christmas Gift Book, another anthology edited by Caine

- 1910 - King Edward: A Prince and a Great Man

- 1914 - King Albert's Book, a tribute to the Belgian King and people

- 1915 - The Drama of 365 Days: Scenes in the Great War

- 1916 - Our Girls: Their Work for the War

- 1928 - Recollections of Rossetti, an expanded version of the earlier book

- 1938 - Life of Christ, published posthumously

In addition he wrote countless articles and stories of which an account has never been kept. The above bibliography is based on that compiled by Allen.[141]

Filmography

- 1911 - The Christian, based on the play. Directed by Franklyn Barrett in Australia. 28 minutes

- 1914 - The Christian, based on the play and the novel. Directed by Frederick A. Thomson in USA.

- 1915 - The Eternal City, based on the play and the novel. Directed by Hugh Ford and Edwin S. Porter in USA. 80 minutes

- 1915 - The Christian, based on the novel. Directed by George Loane Tucker in UK.

- 1916 - The Manxman, based on the novel. Directed by George Loane Tucker in UK. 90 minutes

- 1916 - The Bondman, based on the novel. Directed by Edgar Lewis in USA.

- 1917 - The Deemster, based on the novel (also known as The Bishop's Son). Directed by Howell Hansel in USA.

- 1918 - Victory and Peace. Directed by Herbert Brenon in UK.

- 1919 - The Woman Thou Gavest Me, based on the novel. Directed by Hugh Ford in USA. 60 minutes

- 1923 - The Prodigal Son, based on the novel. Directed by A.E. Coleby in UK and Iceland.

- 1923 - The Christian, based on the play and the novel. Directed by Maurice Tourneur in USA. 80 minutes

- 1923 - The Eternal City, based on the novel. Directed by George Fitzmaurice in USA. 80 minutes

- 1924 - Name the Man based on the novel The Master of Man: the Story of a Sin. Directed by Victor Sjöström in USA. 80 minutes

- 1927 - Barbed Wire, based on the novel The Woman of Knockaloe, a Parable. Directed by Rowland V. Lee in USA. 67 minutes

- 1929 - The Bondman, based on the novel. Directed by Herbert Wilcox in UK.

- 1929 - The Manxman, based on the novel. Directed by Alfred Hitchcock in UK. 90 minutes.

The above filmography is based on the Hall Caine page on the Internet Movie Database[142]

Notes

- ↑ Runcorn Urban District Council (7 September 1931). "Council meeting minutes".

- ↑ "Sunday Times Pert WA". 16 February 1913.

- ↑ "Manx Quarterly, #12". June 1913.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 15.

- ↑ Caine 1908, pp. 3–29.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 16.

- ↑ Caine 1908, p. 9.

- ↑ Moore 1891, pp. 1–18.

- ↑ Kenyon 1905, pp. 21–22.

- ↑ Allen 1997, pp. 17–18.

- ↑ Kenyon 1905, pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Kenyon 1905, p. 30.

- ↑ Kenyon 1905, p. 22.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 23.

- ↑ Caine 1908, p. 35.

- ↑ Burrell, Sean; Gill, Geoffrey (1 October 2005). "The Liverpool Cholera Epidemic of 1832 and Anatomical Dissection—Medical Mistrust and Civil Unrest". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 60 (4): 478–498. doi:10.1093/jhmas/jri061. ISSN 0022-5045.

- ↑ "A walk through the Cholera Districts of Liverpool". www.old-merseytimes.co.uk. Liverpool Journal. 24 November 1849.

- ↑ "The cholera and the burial of cholera victims, 1866". www.old-merseytimes.co.uk. Liverpool Mercury. 20 August 1866.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 26.

- ↑ Kenyon 1905, p. 27.

- ↑ Kenyon 1905, p. 27.

- ↑ Caine 1908, p. 33.

- ↑ Caine 1908, p. 34.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 22.

- ↑ Tirebuck 1903, pp. x - xiii.

- ↑ Caine 1908, pp. 36–38.

- ↑ Caine 1908, pp. 38.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 21.

- ↑ Caine 1908, pp. 38–39.

- ↑ Caine 1908, pp. 38–39.

- ↑ Caine 1908, p. 39.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 26.

- ↑ Caine 1908, p. 40.

- ↑ Caine 1908, p. 43.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 29.

- ↑ Caine 1908, pp. 44-46.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 43.

- ↑ Kenyon 1905, p. 34.

- ↑ Kenyon 1905, p. 36.

- ↑ Kenyon 1905, p. 36.

- ↑ Caine 1908, p. 48.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 31.

- ↑ Caine 1908, p. 50.

- ↑ "Local News". Liverpool Mercury. 5 February 1879.

- ↑ Tirebuck 1903, p. xv.

- ↑ Stoker 1906, p. 115.

- ↑ Kenyon 1905, p. 44.

- ↑ Stoker 1906, p. 115.

- ↑ Kenyon 1905, p. 44.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 44.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 32.

- ↑ Kenyon 1905, p. 52.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 55.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 353.

- ↑ Ritvo 2009, p. 12, 102.

- ↑ Ritvo 2009, pp. 1-6.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 62.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 62.

- ↑ "Notes and Queries. Professor Dowden on the study of Shakespere". Liverpool Mercury. 10 July 1878. p. 8.

- ↑ Kenyon 1905, p. 58.

- ↑ "The Magazines For September". Liverpool Mercury. 3 September 1879. p. 6.

- ↑ Foulkes 2008, p. 55.

- ↑ "Literary Notices,". Liverpool Mercury. 22 February 1879.

- ↑ [The Restoration of Ancient Buildings. Papers by William Morris, Samuel Huggins, J. J. Stevenson, etc., edited by T. H. Hall Caine. Royal Institution, Liverpool. 1877. Crown 8vo. 50 pp.]

- ↑ "Social Science Congress". Liverpool Mercury. 7 October 1879. p. 7.

- ↑ Curtis Jr. 2001, p. 29.

- ↑ Storey 2012, p. 93.

- ↑ Storey 2012

- ↑ Storey 2012

- ↑ Storey 2012, p. 116.

- ↑ Riordan 2009, p. 148.

- ↑ Storey 2012, p. 114.

- ↑ Riordan 2009, p. 148.

- ↑ Riordan 2009, p. 149.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 29.

- ↑ Storey 2012, p. 116.

- ↑ Storey 2012, p. 118.

- ↑ Riordan 2009, p. 150.

- ↑ Storey 2012, p. 120.

- ↑ "An Indian Herb Doctor - Curious Case". Liverpool Mercury. 12 October 1857. p. 2.

- ↑ Storey 2012, p. 123.

- ↑ Storey 2012, p. 128.

- ↑ Riordan 2009, p. 152.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 63, 68.

- ↑ Allen 1997, pp. 69–71.

- ↑ Kenyon 1905, pp. 59-62.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 103.

- ↑ Allen 2000, pp. 25, 36, 110.

- ↑ Allen 1997, pp. 88, 105.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 91.

- ↑ Caine 1908, p. 148.

- ↑ Caine 1908, p. 150.

- ↑ Waugh 2011, p. 228.

- ↑ Caine 1908, p. 212.

- ↑ Caine 1908, pp. 173, 190.

- ↑ Caine 1908, p. 149

- ↑ "The sale of 'Dante's Dream at the time of the Death of Beatrice' to the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool: The Correspondence between D. G. Rossetti and T. H. Caine.". Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 109, 133.

- ↑ Rossetti 1895, p. 384, 387.

- ↑ Rossetti 1895, p. 388, 395.

- ↑ Caine 1882, pp. 294-295.

- ↑ Allen 1997, pp. 88, 141.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 164.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 176.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 178.

- ↑ Allen 1997, pp. 182–183.

- ↑ Allen 1997, pp. 185, 268.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 204.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 211.

- ↑ Allen, Vivien (2011) [2004], "Caine, Sir (Thomas Henry) Hall (1853–1931)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, retrieved 3 August 2013 ((subscription or UK public library membership required))

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 269.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 271.

- ↑ Allen 1997, pp. 279–280.

- ↑ Allen 1997, pp. 153, 325–327.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 351.

- ↑ Caine, Hall (ed.), King Albert's Book, a Tribute to the Belgian King and People from representative men and women throughout the World (The Daily Telegraph, in conjunction with The Daily Sketch, The Glasgow Herald and Hodder & Stoughton, Christmas 1914) "Sold in aid of the Daily Telegraph Belgian Fund."

- ↑ Allen 1997, pp. 380–381.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 430.

- ↑ Allen 1997, pp. 282–284.

- ↑ Brownlow 1990, p. 457.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 416.

- ↑ Allen 1997, pp. 35–36.

- ↑ Allen 1997, pp. 24, 213.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 159.

- ↑ Allen 1997, pp. 159–160.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 176. Now held in the Manx Museum, Douglas

- ↑ Allen 1997, pp. 205–206.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 292.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 313.

- ↑ Allen 1997, pp. 348–350.

- ↑ Allen 1997, pp. 388–389.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 423.

- ↑ Allen 1997, p. 7.

- ↑ Allen 1997, pp. 430–431.

- ↑ Hall Caine Airport, Mers Online, retrieved 2007-09-02

- ↑ J. Sutherland, The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction (1990) p. 97-9

- ↑ I. Ousby ed., The Cambridge Guide to Literature in English (1995) p. 144

- ↑ A DEFENCE OF PENNY DREADFULS at www.cse.dmu.ac.uk

- ↑ M. Seymour-Smith, Thomas Hardy (1994) p. 645

- ↑ Princess Mary's Gift Book available on www.archive.org (accessed 23 March 2015)

- ↑ Allen 1997, pp. 433–435.

- ↑ Hall Caine at the Internet Movie Database

References

- Caine, Hall (1908), My Story, London: Collier & Co

- Kenyon, Charles Fredrick (1901), Hall Caine: The Man and the Novelist, London: Greening & Co Ltd

- Allen, Vivien (1997), Hall Caine: Portrait of a Victorian Romancer, Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, ISBN 1-85075-809-3

- Brownlow, Kevin (1990), Behind the Mask of Innocence, New York: Alfred Knopf, ISBN 978-0-520-07626-6

- Moore, A.W. (1891), The Folk-Lore of the Isle of Man, Isle of Man: Brown & Son

- Tirebuck, William Edwards (1903), Twixt God and Mammon, New York: D. Appleton and Company

- Stoker, Bram (1906), Personal Reminiscences of Henry Irving Volume II, London: William Heinemann

- Ritvo, Harriet (2009), The Dawn of Green: Manchester, Thirlmere, and Modern Environmentalism, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 9780226720821

- Foulkes, Richard (2008), Henry Irving: ARe-Evaluation of the Pre-Eminent Victorian Actor-Manager, Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Limited, ISBN 978-1-138-66565-1

- Riordan, Timothy B. (2009), Prince of Quacks: The Notorious Life of Dr. Francis Tumblety, Charlatan and Jack the Ripper Suspect, Jefferson, North Carolina, and London: MaFarland & Company, Inc, ISBN 978-0-786-44433-5

- Storey, Neil R. (2012), The Dracula Secrets: Jack the Ripper and the Darkest Sources of Bram Stoker, Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press, ISBN 978-0-752-48048-0

- Caine, Hall (1882), Recollections of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, London: Elliot Stock

- Rossetti, William Michael (1895), Dante Gabriel Rossetti; his family-letters, with a memoir by William Michael Rossetti, London: Ellis and Elvey

- Allen, Vivien (2000), Dear Mr Rossetti: The Letters of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Hall Caine 1878-1881, Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, ISBN 1-84127-049-0

Footnotes

- ↑ House numbers were not in use in Bridgewater Street at the time of Caine's birth.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hall Caine. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Caine, Thomas Henry Hall. |

- Works by Hall Caine at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Hall Caine at Internet Archive

- Works by Hall Caine at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Hall Caine's page on the Manx Literature website

- Information from manxnotebook website

- "Archival material relating to Hall Caine". UK National Archives.

- Portraits in the National Portrait Gallery

- The Sir Hall Caine Papers (Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University, Houston, TX, USA)

- Film footage of Hall Caine and son, Derwent, in the middle of the film, The King's Ride in the Isle of Man (1902), from the BFI