High Speed 1

| High Speed 1 | |

|---|---|

| |

|

High Speed 1 approaching the Medway Viaducts. | |

| Overview | |

| Type |

High-speed rail Heavy rail |

| Status | Operational |

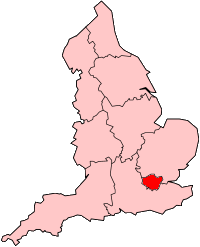

| Locale |

Greater London Essex Kent South East England |

| Termini |

London St Pancras Channel Tunnel (UK portal) |

| Stations | 4 |

| Operation | |

| Opened |

2003 (Section 1) 2007 (Section 2) |

| Owner |

UK Government Borealis Infrastructure and Ontario Teachers' Pension Plan (concession until 2040) |

| Operator(s) | Eurostar, Southeastern, DB Cargo UK |

| Rolling stock |

|

| Technical | |

| Line length | 108 km (67 mi) |

| Number of tracks | Double track throughout |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge |

| Loading gauge | UIC GC[2] |

| Electrification | 25 kV 50 Hz OHLE |

| Operating speed |

300 km/h (186 mph) on section 1, 230 km/h (143 mph) on section 2[3][4][5] |

| High Speed 1 / Channel Tunnel Rail Link | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Legend | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

High Speed 1 (HS1), legally the Channel Tunnel Rail Link (CTRL), is a 109-kilometre (68 mi) high-speed railway between London and the United Kingdom end of the Channel Tunnel.

The line carries international passenger traffic between the United Kingdom and Continental Europe; it also carries domestic passenger traffic to and from stations in Kent and east London, and Berne gauge freight traffic. The line crosses the River Medway, and under the River Thames, terminating at St Pancras railway station on the north side of central London. It cost £5.8 billion to build and opened on 14 November 2007.[6][7] Trains reach speeds of up to 300 kilometres per hour (186 mph) on section 1 and up to 230 kilometres per hour (143 mph) on section 2. Intermediate stations are at Stratford International in London and Ebbsfleet International and Ashford International in Kent.

International passenger services are provided by Eurostar, with journey times of London St Pancras to Paris Gare du Nord in 2 hours 15 minutes, and St Pancras to Brussels-South in 1 hour 51 minutes.[8] As of November 2015, Eurostar has used a fleet of 27 Class 373/1 multi-system trains capable of 300 kilometres per hour (186 mph) and 320 kilometres per hour (199 mph) Class 374 trains. Domestic high-speed commuter services serving the intermediate stations and beyond began on 13 December 2009. The fleet of 29 Class 395 passenger trains reach speeds of 225 kilometres per hour (140 mph).[9] DB Cargo UK run freight services on High Speed 1 using adapted Class 92 locomotives, enabling flat wagons carrying continental-size swap body containers to reach London for the first time.[10]

The CTRL project saw new bridges and tunnels built, with a combined length nearly as long as the Channel Tunnel itself, and significant archaeological research undertaken.[11] In 2002, the CTRL project was awarded the Major Project Award at the British Construction Industry Awards.[12] The line was transferred to government ownership in 2009, with a 30-year concession for its operation being put up for sale in June 2010.[13] The concession was awarded to a consortium of Borealis Infrastructure (part of Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System) and Ontario Teachers' Pension Plan in November 2010,[14] but does not include the freehold or rights to any of the associated land.[15]

Early history

A high-speed rail line, LGV Nord, has been in operation between the Channel Tunnel and the outskirts of Paris since the Tunnel's opening in 1994.[16] This has enabled Eurostar rail services to travel at 300 km/h (186 mph) for this part of their journey. A similar high-speed line in Belgium, from the French border to Brussels, HSL 1, opened in 1997.[17][18] In Britain, Eurostar trains had to run at a maximum of 160 km/h (100 mph) on existing tracks between London Waterloo and the Channel Tunnel.[19] These tracks were shared with local traffic, limiting the number of services that could be run, and jeopardising reliability.[20] The case for a high-speed line similar to the continental part of the route was recognised by policymakers,[21] and the construction of the line was authorised by Parliament with the Channel Tunnel Rail Link Act 1996,[22] which was amended by the Channel Tunnel Rail Link (Supplementary Provisions) Act 2008.[23][24]

An early plan conceived by British Rail in the early 1970s for a route passing through Tonbridge met considerable opposition on environmental and social grounds, especially from the Leigh Action Group and Surrey & Kent Action on Rail (SKAR). A committee was set up to examine the proposal under Sir Alexander Cairncross; but in due course environment minister Anthony Crosland announced that the project had been cancelled,[25] together with the plan for the tunnel itself.

The next plan for the Channel Tunnel Rail Link involved a tunnel reaching London from the south-east, and an underground terminus in the vicinity of Kings Cross station. A late change in the plans, principally driven by the then Deputy Prime Minister Michael Heseltine's desire for urban regeneration in east London, led to a change of route, with the new line approaching London from the east. This opened the possibility of reusing the underused St Pancras station as the terminus, with access via the North London Line that crosses the throat of the station.[26]

The idea of using the North London line proved illusory, and it was rejected in 1994 by the then Transport Secretary, John MacGregor, as too difficult to construct and environmentally damaging.[27] The idea of using St Pancras station as the core of the new terminus was retained, albeit now linked by 20 kilometres (12 miles) of specially built tunnels to Dagenham via Stratford.[26]

London and Continental Railways (LCR) was chosen by the UK government in 1996 to build the line and to reconstruct St Pancras station as its terminus, and to take over the British share of the Eurostar operation, Eurostar (UK). The original LCR consortium members were National Express Group, Virgin Group, S. G. Warburg & Co, Bechtel and London Electric.[28][29] While the project was under development by British Rail it was managed by Union Railways, which became a wholly owned subsidiary of LCR. On 14 November 2006, LCR adopted High Speed 1 as the brand name for the completed railway.[30] Official legislation, documentation and line-side signage have continued to refer to "CTRL".

The project

As the 1987 Channel Tunnel Act made government funding for a Channel tunnel rail link unlawful,[31] construction did not take place as it was not financially viable. Construction was delayed until passage of the Channel Tunnel Rail Link Act 1996[22] which provided construction powers that ran for the following 10 years. The chief executive of the time Rob Holden stated that it was the "largest land acquisition programme since the Second World War".[32]

The whole route was to have been built as a single project, but in 1998 serious financial difficulties arose, and extensive changes came with a British government rescue plan.[33] To reduce risk, the line was split into two separate phases,[34] to be managed by Union Railways (South) and Union Railways (North). A recovery programme was agreed whereby LCR sold government-backed bonds worth £1.6 billion to pay for the construction of section 1, with the future of section 2 still not settled.

The original intention had been for the new railway, once completed, to be run by Union Railways as a separate line from the rest of the British railway network. As part of the 1998 rescue it was agreed that, following completion, section 1 would be purchased by Railtrack with an option to purchase section 2. In return, Railtrack was committed to operate the whole route as well as St Pancras railway station, which, unlike all other former British Rail stations, had been transferred to LCR/Union Railways in 1996.[35]

In 2001, Railtrack announced that, due to its own financial problems, it would not undertake to purchase section 2,[36][37][38] triggering a second restructuring.[39] The 2002 plan agreed that the two sections would have different owners (Railtrack for section 1, LCR for section 2) but with common Railtrack management. Following further financial problems at Railtrack,[40] its interest was sold back to LCR, which then sold the operating rights for the completed line to Network Rail, Railtrack's successor.[41] Under this arrangement LCR became the sole owner of both sections of the CTRL and the St Pancras property, as per the original 1996 plan. Amendments were made in 2001 for the new station at Stratford International and connections to the West Coast Main Line.

As a consequence of the restructuring, in 2006 the LCR consortium consisted of engineering consultants and construction firms Arup, Bechtel, Halcrow and Systra (which form Rail Link Engineering (RLE)); transport operators National Express Group and SNCF (which operates the Eurostar (UK) share of the Eurostar service with the National Railway Company of Belgium and British Airways); electricity company EDF; and UBS Investment Bank. On completion of section 1 by RLE, the line was handed over to Union Railways (South), which then handed it over to London & Continental Stations and Property (LCSP), the long-term owners of the line. Once section 2 of the line had been completed it was handed over to Union Railways (North), which handed it over to LCSP. The entire line, including St Pancras, is managed, operated and maintained by Network Rail (CTRL).

In February 2006 there were rumours that a 'third party' (believed to be a consortium headed by banker Sir Adrian Montague) had expressed an interest in buying out the present partners in the project.[42] LCR shareholders rejected the proposal,[43] and the government, which effectively could overrule shareholders' decisions as a result of LCR's reclassification as a state-owned body,[44] decided that discussions with shareholders would not take place imminently, effectively backing shareholders' views on the proposed takeover.[43]

By May 2009 LCR had become insolvent and the government received agreement to use state aid to purchase the line and also to open it up to competition to allow other services to use it apart from Eurostar.[45] LCR's hitherto wholly owned subsidiary, HS1 Ltd, thus became the property of the Secretary of State for Transport.[46] On 12 October 2009 a proposal was announced to sell £16 billion of state assets including HS1 Ltd in the following two years to cut UK public debt.[47] The government announced on 5 November 2010 that a concession to operate the line for 30 years had been sold for £2.1 billion to a consortium of Canadian investors.[14] Under the concession, HS1 Ltd has the rights to sell access to track and to the four international stations (St Pancras, Stratford, Ebbsfleet and Ashford) on a commercial basis, under the scrutiny of the Office of Rail Regulation. At the end of 30 years, ownership of the assets will revert to government.[46]

Building cost

The cost of construction, £80 million per mile, was much higher than other projects in other countries; the French high speed line from Paris to Strasbourg, completed in 2007, cost £22 million per mile.[48]

Route

The high-speed railway operates as a "seven-day railway", with full availability on all days. The line is closed for 40 minutes in the middle of the day shortly after noon for a "white period" (French: période blanche) and "daylight inspection period". Any heavy maintenance is performed overnight.[49][50][51]:21 As of 2008 track access charges were capped at approximate £71.35 per minute. In 2008 the cost of running a train along the full length of the line between St Pancras and the Channel Tunnel was £2,244; with lower costs of £2,192 for a domestic service to Ashford International, or £1,044 for St Pancras to Ebbsfleet International.[51]:6 A discounted rate of £4.00 per kilometre was made available for night-time-only railfreight operation until 31 March 2015.[52]

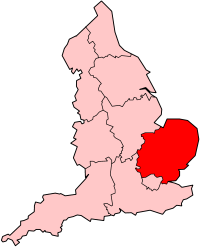

Section 1

Section 1 of the Channel Tunnel Rail Link, opened on 28 September 2003, is a 74-kilometre (46 mi) section of high-speed track from the Channel Tunnel to Fawkham Junction in north Kent with a maximum speed of 300 kilometres per hour (186 mph). Its completion cut the London–Paris journey time by around 21 minutes, to 2 hours 35 minutes. The line includes the Medway Viaduct, a 1.2 km (¾ mile) bridge over the River Medway, and the North Downs Tunnel, a 3.2 km (2.0 mi) long, 12 m (40 ft) diameter tunnel. In safety testing on the section prior to opening, a new UK rail speed record of 334.7 km/h (208.0 mph) was set.[53] Much of the new line runs alongside the M2 and M20 motorways through Kent. After its completion, Eurostar trains continued to use suburban lines to enter London, arriving at Waterloo International.

There were several deaths of employees working on the CTRL over the construction period. One occurred on 28 March 2003 near Folkestone when a worker came into contact with the energised power supply.[54] Another death occurred two months later, in May 2003, when a scaffolder fell seven metres at Thurrock, Essex.[55] Three companies were found guilty of breaching health and safety legislation by omitting to provide barriers, resulting in Deverson Direct Ltd being ordered to pay a fine of £50,000, J Murphy and Sons Ltd £25,000, and Hochtief Aktiengesellschaft £25,000.[55] Two more deaths relate to a fire on board a train carrying wires, one mile (1.6 km) inside a tunnel under the Thames between Swanscombe, Kent, and Thurrock, Essex on 16 August 2005. The train shunter died at the scene[56] and the train driver later died in hospital.[57] It has been suggested that a large amount of blame for accidents throughout the project lay with individual behaviour, becoming such a problem that an internal programme was launched to tackle behaviour problems during the construction.[58]

Unlike most LGV stations in France, the through tracks for Ashford International station are off to one side rather than going through, partly due to Ashford International predating the line.[59] High Speed 1 approaches Ashford International from the north in a cut-and-cover "box"; the southbound line rises out of this cutting and crosses over the main tracks to enter the station. The main tracks then rise out of the cutting and over a flyover. On leaving Ashford, southbound Eurostars return to the high-speed line by travelling under this flyover and joining from the outside. The international platforms at Ashford are supplied with both overhead 25 kV and 3rd rail 750 V, avoiding the need to switch power supplies.

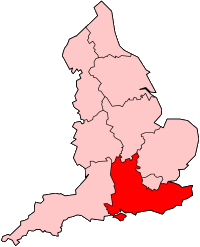

Section 2

Section 2 of the project opened on 14 November 2007 and is a 39.4 km (24.5 mi) stretch of track from the newly built Ebbsfleet station in Kent to London St Pancras with a maximum speed of 230 kilometres per hour (143 mph). Completion of the section cut journey times by a further 20 minutes (London–Paris in 2h 15 m; London–Brussels in 1h 51 m). The route starts with a 2.5-kilometre (1.6 mi) tunnel which dives under the Thames on the edge of Swanscombe, then runs alongside the London, Tilbury and Southend Railway as far as Dagenham, where it enters a 19-kilometre (12 mi) tunnel (51°31′36.9″N 0°8′13.9″E / 51.526917°N 0.137194°E), much of which is directly under the North London Line, before emerging over the East Coast Main Line near St Pancras. The tunnels are divided into London East and London West sections, between which a 1-kilometre stretch runs close to the surface to serve Stratford International and the Temple Mills Depot.

The new depot at Temple Mills, to the north of Stratford, replaced the North Pole depot in the west of London.[60] In testing, the first Eurostar train ran in St Pancras on 6 March 2007.[61] All CTRL connections are fully grade-separated. This is achieved through use of viaducts, bridges, cuttings and in one case, the tunnel portal itself.

Stations

Ashford International

This station was rebuilt as Ashford International during the early 1990s for international services from mainland Europe; this included the addition of two platforms to the north of station (the original down island platform had been taken over by international services). Unlike normal LGV stations in France, the through tracks for Ashford International railway station are off to one side rather than going through.[59] The number of services was reduced after the opening of the Ebbsfleet station. A high-speed domestic service operated by Southeastern to London St Pancras began on 29 June 2009.

Ebbsfleet International

Ebbsfleet International railway station in the borough of Dartford, Kent is 10 mi (16 km) outside the eastern boundary of Greater London and opened to the public on 19 November 2007.[62] It is now Eurostar's main station in Kent.[63][64][65] Two of the platforms are designed for international passenger trains and four for high-speed domestic services.[66]

St Pancras International

The terminus for the high-speed line in London is St Pancras railway station. During the 2000s, towards the end of the construction of the CTRL, the entire station complex was renovated, expanded and rebranded as St Pancras International,[67][68] with a new security-sealed terminal area for Eurostar trains to continental Europe.[69] In addition, it retained traditional domestic connections to the north and south of England. The new extension doubled the length of the central platforms now used for Eurostar services; new platforms have been provided for existing domestic East Midlands Trains and the Southeastern high-speed services that run along High Speed 1 to Kent.[70] New platforms on the Thameslink line across London were built beneath the western margins of the station, and the station at King's Cross Thameslink was closed.

A complex junction has been built north of St Pancras with connections to the East Coast Main Line, North London Line (for West Coast Main Line) and Midland Main Line, allowing for a wide variety of potential destinations albeit on conventional rails. As part of the works, tunnels connecting the East Coast Main Line to the Thameslink route were also built in readiness for the forthcoming Thameslink Programme.

Stratford International

Stratford International railway station was not part of the original government plans for the CTRL.[71] Despite its name, no international services call there. Completed in April 2006, it opened on 30 November 2009 when the domestic preview Southeastern highspeed services started calling there.[72] An extension of the Docklands Light Railway opened to Stratford International in August 2011.[73] It forms part of the complex of railway stations for the main site where the 2012 Summer Olympics were held.[74]

Temple Mills Depot in Leyton is used for storage and servicing of Eurostar trains and off-peak berthing of Class 395 Southeastern high-speed trains.

Infrastructure

The railway is maintained from Singlewell Infrastructure Maintenance Depot. Access to the railway is protected by over one thousand Assa Abloy padlocks, with a hierarchical system of master keys.[75]

Track

Both track and signalling technology (TVM-430 + KVB) are based on or identical to the standards used on the French LGV high-speed lines. The areas around St Pancras and Gare du Nord use colour light and KVB signalling[76] with the whole of the high-speed route to Paris (CTRL, Channel Tunnel, LGV Nord) using TVM-430. Traffic is controlled from the Ashford signalling centre. Signalling tests before opening were performed by the SNCF-owned "Lucie" test car.[77]

The track is 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge[2] cleared to a larger modern European GC loading gauge[2] enabling GC gauge freight as far as the yards at Barking.[78][79] The line is electrified entirely using overhead lines with 25 kV AC railway electrification.

Tunnels

After local protests,[80][81] early plans were modified to put more of the route into tunnels up until a point approximately 1 mile (2 km) from St. Pancras. Previously the CTRL was planned to run on an elevated section alongside the North London Line on approach into the line's terminus. The twin tunnels bored under London were driven from Stratford westwards towards St Pancras, eastwards towards Dagenham and from Dagenham westwards to connect with the tunnel from Stratford. The tunnel boring machines were 120 metres long and weighed 1,100 tonnes. The depth of the tunnels varies from 24 metres to 50 metres.

The construction works were complex, and many contractors were involved in delivering them.[82] The CTRL Section 2 construction works had caused considerable disruption around the Kings Cross area of London; in their wake redevelopment was stimulated.[83][84] The large redevelopment area includes the run-down areas of post-industrial and ex-railway land close to King's Cross and St Pancras, a conservation area with many listed buildings; this was promoted as one of the benefits for building the CTRL.[85] It has been postulated that this development was actually suppressed by the construction project,[86] and some affected districts were said still to be in a poor state in 2005.[87]

Connection line to Waterloo

A 4-kilometre (2.5 mi) connecting line providing access for Waterloo railway station leaves High Speed 1 at Southfleet Junction using a grade-separated junction; the main CTRL tracks continue uninterrupted through to CTRL Section 2 underneath the southbound flyover. The connection joins the Chatham Main Line at Fawkham Junction with a flat crossing. The retention of Eurostar services to Waterloo after the line to St Pancras opened was ruled out on cost grounds.[88] Waterloo International closed upon opening of the section two of the CTRL in November 2007; Eurostar now serves the refurbished St Pancras as its only London terminal, so this connecting line is no longer used in regular service,[89][90] but can be used in emergencies by Class 395 passenger trains.[91]

Services

High Speed 1 was built to allow eight trains per hour through to the Channel Tunnel.[92] As of May 2014, Eurostar runs two to three trains per hour in each direction between London and the Channel Tunnel.[93] Southeastern runs in the high peak eight trains per hour between London and Ebbsfleet, two of these continuing to Ashford.[94] During the 2012 Olympic Games, Southeastern provided the Olympic Javelin service with up to twelve trains per hour from Stratford into London.[95]

Freight

The route was built with freight provision from the beginning. It has spurs leading to and from the freight terminal at Dollands Moor (Folkestone) and the freight depot at Barking (Ripple Lane), north of the River Thames. Long passing loops to hold freight trains while passenger trains overtake them were built at Lenham Heath and Singlewell.

Freight trains operated by EWS first ran over CTRL Section 1, on the consecutive evenings of 3–4 April 2004. Five freight trains that would have run via the classic lines were diverted to run over the Channel Tunnel Rail Link instead: three southbound intermodal trains on 3 April 2004 and two northbound intermodal trains on 4 April 2004.[96]

Ownership

In November 2010, the HS1 concession was awarded for a duration of thirty years to an investment consortium bringing together two Canadian public pension funds: Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System (through its subsidiary Borealis Infrastructure ) and Ontario Teachers' Pension Plan [14] At the time, UK pension investors had generally limited interest for such long-term, illiquid, ‘infrastructure assets’ [97]

Operators

The railway is operated on an open access basis. Trains are operated by several organisations all operating over the same track. HS1 Ltd. is the network manager for the line, stations, and other infrastructure.[98]

Network Rail (High Speed) Ltd

HS1 Ltd is responsible for overall managing and running of the line—along with the international railway stations at St Pancras, Stratford, Ashford and Ebbsfleet[99]—with responsibility for the infrastructure itself sub-contracted to Network Rail (High Speed) Ltd (formerly known as Network Rail (CTRL) acting as the controller and infrastructure manager.[100] Network Rail (CTRL) Limited was created as a subsidiary of Network Rail on 26 September 2003 for £57 million to take over the assets of the CTRL renewal and maintenance operations.[101] Network Rail (High Speed) operates engineering, track maintenance machines, rescue locomotives, and infrastructure- and test trains.[102] Eurotunnel's subsidiary Europorte 2 operates its Eurotunnel Class 0001 (Krupp/MaK 6400) rescue locomotives on the line when required.[103]

Various track recording trains run as necessary, including visits by the New Measurement Train. On the night of 4/5 May 2011 the SNCF TGV Iris 320 laboratory train took over, being hauled from Coquolles to St Pancras and back, towed by Eurotunnel Krupp locomotives numbers 4 and 5.[104] The Iris 320 runs for Network Rail (High Speed) are an extension of the 100 km/h (62 mph) monitoring cycle already undertaken by SNCF International since December 2010 for Eurotunnel every two months.[105][106]

Eurostar

The Eurostar service uses about 40% of the capacity of High Speed 1,[107] which in November 2007 became the company's route for all its services.[108] Eurostar trains are for international traffic only, passing along the high-speed line from London St Pancras railway station to the Channel Tunnel, with the majority[109] terminating at either Paris Gare du Nord in France or Brussels-South railway station in Belgium.[110][111] Currently the trains operated by Eurostar are the only ones to make full use of the high speeds on the line; a Eurostar train was used to set a new British rail speed record of 334.7 km/h (208 mph) on 30 July 2003.[112][113] Prior to the formation of Eurostar International Limited, the British component of the Eurostar grouping was owned by London and Continental Railways, which had also previously owned the High Speed 1 infrastructure.[114]

The fastest regular-service Eurostar journeys on record are 2 hours, 3 minutes and 39 seconds from Paris Gare du Nord to St Pancras, set on 4 September 2007;[115] and 1 hour 43 minutes from Brussels South to St. Pancras, set on 19 September 2007.[116]

| Class | Image | Type | Top speed | Number | Routes operated | Built | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mph | km/h | ||||||

| Class 373 Eurostar e300 |

EMU | 186 | 300 | 28 | London–Paris London–Brussels London–Marne-la-Vallée – Chessy London–Bourg Saint Maurice London - Marseille - Saint-Charles |

1992-1996 | |

| Class 374 Eurostar e320 |

|

EMU | 200 | 320 | 17 | 2011-2018 | |

Southeastern

Domestic high-speed services on High Speed 1 are operated by Southeastern. Having been in planning since 2004,[117] a preview service of the British Rail Class 395 trains, popularly known as Javelins, started in June 2009,[66] and regular services began on 13 December 2009. The quickest journey time from Ashford to London St Pancras is 35 minutes,[118] compared with 80 minutes for the service to London Charing Cross via Tonbridge.[119] This service on Section 2 of the CTRL, known previously as CTRL-DS, was a factor in London's successful 2012 Olympic Bid, promising a seven-minute journey time from the Olympic Park at Stratford to the London terminus at St Pancras.[120] Although the Class 395 has a maximum speed of 225 km/h (140 mph), for timetabling purposes a 10% lower speed is assumed.[121] These trains have faster acceleration than the Eurostar units.[122]

| Class | Image | Type | Top speed | Number | Routes operated | Built | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mph | km/h | ||||||

| Class 395 |  |

Electric multiple unit | 140 | 225 | 29 | St Pancras–Stratford International- Ebbsfleet International-Ashford International-Ramsgate/ Dover Priory.[123] Faversham -Strood-Gravesend-St Pancras[124] |

2007–2009 |

DB Cargo UK

DB Cargo is a global freight operator with a large interest in freight over rail in Europe.[125] While High Speed 1 was constructed with freight loops, no freight traffic had run upon the line since opening in 2003.[126] On 16 April 2009 DB Schenker signed an agreement with HS1 Ltd, the owner of High Speed 1, for a partnership to develop TVM modifications for class 92 freight locomotives to run on the line.[127] On 25 March 2011 for the first time a modified class 92 locomotive travelled from Dollands Moor to Singlewell using the TVM430 signalling system.[1] A loaded container train ran for the first time on 27 May 2011, to Novara in Italy. Following further trials with loaded wagons[128][129] DB is to upgrade five Class 92 locomotives to allow them to run on High Speed 1.[130] From 11 November 2011 a weekly service using European-sized swap body containers has run between London and Poland using High Speed 1.

| Class | Image | Type | Top speed | Number | Built | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mph | km/h | ||||||

| Class 92 |  |

Electric locomotive | 87 | 140 | 46 | 1993–1996 | 92009, 92015, 92016, 92031, 92042 to be converted for High Speed 1 usage with the necessary TVM modifications.[131] |

Future operations

At present, only Deutsche Bahn has applied for use of the line and in 2009 regulations were relaxed to allow its trains to use the Channel Tunnel. Other proposals are yet to be formalised.

Deutsche Bahn

In November 2007, it was reported that Deutsche Bahn, Germany's national train company, had applied to use the Channel Tunnel and High Speed 1 into London.[132] This was denied by Deutsche Bahn, and the bi-national Channel Tunnel Safety Authority confirmed that it had not received such an application.[133] The plan was delayed by safety regulations as Deutsche Bahn's fleet of ICE 3M high-speed trains could not be divided in the tunnel in an emergency.[134]

In December 2008, it was reported that Deutsche Bahn (DB) was interested in buying the British share in Eurostar,[135] which in practice means buying Eurostar (U.K.) Ltd., the 100% subsidiary of London and Continental Railways (LCR), which the British government intends to break up and sell just as it does the other rail-related subsidiary of L&CR, HS1 Ltd.[136][137] The buyer of EUKL would become the owner of the 11 British "Three Capitals" Class 373 trainsets plus all seven "North of London" sets, and would also be responsible for the operations of Eurostar traffic within Britain once the management contract with ICRR expires in 2010. Guillaume Pépy, the president of SNCF, who held a press conference the same day, described DB's interest as "premature, presumptuous and arrogant".[138] SNCF claims to own 62% of the shares of Eurostar Group Ltd. Hartmut Mehdorn, then CEO of Deutsche Bahn, confirmed DB's interest but insisted in a letter to Pépy that DB had only informally requested information and not made any official requests to Britain's Department for Transport.[139]

In 2009, Eurotunnel (the owners of the Channel Tunnel) announced that it was prepared to start relaxing the fire safety regulations, in order to permit other operators, such as Deutsche Bahn, to transport passengers via the Tunnel using other forms of rolling stock.[140] Under the deregulation of European railway service, high-speed lines were opened up to access by other operators on 1 January 2010; the Inter-Governmental Commission on the Channel Tunnel (IGC) announced that it was considering relaxing the safety requirements concerning train splitting. LCR suggested that high-speed rail services between London and Cologne could commence before the 2012 Olympics.[141]

In March 2010 Eurotunnel, HS1 Ltd, DB and other interested train operators formed a working group to discuss changes to the safety rules, including allowing 200-metre trains. The Intergovernmental Commission currently requires trains to be 400 m long.[142] Deutsche Bahn carried out evacuation trials in the tunnel on 17 October 2010 with two 200m-long ICE3 trains, and displayed one of them at St Pancras station on 19 October.[143] The current Velaro ICE3 sets do not meet the fire safety requirements for passenger services through the tunnel, but the Siemens Velaro D sets on order include the necessary additional fire-proofing.[144] In March 2011, the European Rail Agency decided to allow trains with distributed traction to operate in the Channel Tunnel.[145] DB is planning three services a day to Frankfurt (5h from London), Rotterdam (3h) and Amsterdam (4h) via Brussels[143][146] from 2015. This had originally planned to be 2013, but has been delayed due to the availability of the Channel Tunnel version of the Siemens Velaro D trains, high rental costs of the French rail network and border controls in their stations.[147] As of 2016, nothing yet has come to fruition, but the High Speed One website continues to state that "HS1 Ltd are working with Deutsche Bahn on plans to incorporate three additional international return journeys, between Frankfurt and London via Cologne, Brussels and Lille. This will include connections from Amsterdam via Rotterdam to London."[148]

Veolia

In September 2008, Air France-KLM indicated a desire to take advantage of the change in the law and apply to run rail services, in cooperation with Veolia, from London to Paris and from Paris to Amsterdam, in competition with Eurostar and Thalys respectively, with the intention of purchasing or leasing the new AGV multiple units currently being tested.[149][150] In October 2009 Air France withdrew its interest. This led to Veolia looking for new partners, with the announcement that it would begin working on new proposals in cooperation with Trenitalia to run services from Paris to Strasbourg, London and Brussels.[151]

Renfe

Spanish railway operator RENFE has also shown an interest in running AVE services from Spain to London[152] via Paris, Lyon, Barcelona, Madrid and Lisbon (using the Madrid–Barcelona high-speed rail line) once its AVE network is connected to France via the Barcelona to Figueres and Perpignan to Figueres lines in 2012.[153]

Transmanche Metro

In February 2010, local councillors from Kent and Pas-de-Calais announced they were in talks to establish a frequent local rail service between the regional stations along the route. Trains would leave Lille and stop at Calais, Ashford and Stratford before reaching London St. Pancras. Currently, Ashford and Calais have an infrequent service and Eurostar trains do not call at Stratford. The initiative is part of Calais' branding as part of the UK in order to benefit from the 2012 London Olympics but is supported on both sides of the channel to bring in more commuters.[154]

See also

- High Speed 2

- High-speed rail in the United Kingdom

- Megaproject

- Rail transport in the United Kingdom

- Shortlands railway station (dive-under at Shortlands Junction built in conjunction with HS1)

- Transport in London

References

- 1 2 "European sized rail freight to arrive in the UK soon, following successful locomotive trial" (Press release). DB Schenker Rail (UK). 25 March 2011. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

- 1 2 3 "HS1 Network Statement" (PDF). HS1 Limited. 17 August 2009. pp. 17, 19.

3.3.1.2 Track Gauge & Structure Gauge: The nominal track gauge is 1435 mm. ... 3.3.2.1 Loading Gauge: … UIC "GC" on HS1; and UIC "GB+" on Ashford connecting lines … Waterloo connection .. structure gauge (W6/W6A)

- ↑ "Channel Tunnel Rail Link Visit" (PDF). Institute of Sound and Vibration Research, University of Southampton. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 July 2004. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

Section 2, which has a line speed of 225 km/h

- ↑ "Building Britain's first high speed line". Railway Gazette International. London. 1 May 1999. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

Speed will be reduced to 225 km/h (140 mph) between Ebbsfleet and St Pancras, primarily for aerodynamic reasons in the tunnels.

- ↑ "HS1 (Section 2) Register of Infrastructure" (PDF). HS1 Ltd. para. 1.4. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

Maximum allowable speed; Maximum speed of any (interoperable or otherwise) operating on Section 2 of the HS2: Passenger 225 km/h, Freight 140 km/h

- ↑ "High Speed 1". railway-technology.com. 23 December 2008. Retrieved 23 December 2008.

- ↑ "High Speed One – and Only". RailStaff. 14 November 2006. Retrieved 14 November 2006.

- ↑ "Eurostar to launch passenger services at St Pancras International on Wednesday 14 November 2007" (Press release). Eurostar. 14 November 2006. Retrieved 15 November 2006.

- ↑ "Southeastern Highspeed". Southeastern Railway. 1 December 2009. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ↑ Haigh, Philip (10 August 2011). "DB a step closer to European freight into London via HS1". Rail. Peterborough. p. 15.

- ↑ Matthews, Roger (2003). The archaeology of Mesopotamia: theories and approaches. London: Routledge. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-415-25317-8.

The development of this new railway resulted in the largest archaeological project to date in the United Kingdom

- ↑ Mylius, Andrew (2 November 2006). "CTRL team scoops BCI Major Project Award". New Civil Engineer. London. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ↑ "High-speed London to Folkestone rail link up for sale". BBC News. 21 June 2010. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- 1 2 3 "High Speed 1 concession awarded to Canadian pension consortium". Railway Gazette International. London. 5 November 2010.

- ↑ Milmo, Dan (28 January 2011). "Highest bidder asks why it lost Channel tunnel rail link sale". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

[the] transport secretary … stressed that the deal did not include the railway's freehold or the land itself.

- ↑ "Bilan LOTI de la LGV Nord Rapport" (PDF) (in French). Cgedd Developpement. Retrieved 10 May 2009.

- ↑ "Infrabel celebrates 10 years of the High Speed Line in Belgium" (Press release). Infrabel. 14 December 2007.

- ↑ "Detailed map layout of Belgian railway transportation network" (PDF). Infrabel. Retrieved 13 May 2009.

- ↑ Harper, Keith (18 January 2001). "French attack Railtrack". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- ↑ "How the need for a CTRL developed". Department for Transport. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- ↑ Harrison, Michael (18 June 1993). "2001: a rail odyssey drags on: Plans for a Channel tunnel link are finally gathering speed". The Independent. London. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- 1 2 "Channel Tunnel Rail Link Act 1996 c61". 1996. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- ↑ "Channel Tunnel Rail Link (Supplementary Provisions) Act 2008 c5". 2008. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- ↑ "HC Hansard Volume 467 Part 3 Column 259". Hansard. Parliament of the United Kingdom. 8 November 2007. Retrieved 31 August 2008.

- ↑ Hansard 20 January 1975

- 1 2 Timpson, Trevor (14 November 2007). "How St Pancras was chosen". BBC News. Retrieved 19 November 2007.

- ↑ Goodwin, Stephen (21 January 1994). "Inside Parliament: Euro-sceptic derides 'white elephant' line". The Independent. London. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- ↑ "Britain's Channel Tunnel rail link (four contract contenders named)". Railway Age. accessmylibrary.com. 1 September 1995. Retrieved 1 August 2009. (subscription required)

- ↑ Wolmar, Christian (4 July 1995). "Branson in last round of rail link fight". The Independent. London. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- ↑ "High-speed rail link open in year". BBC News. 14 November 2006. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- ↑ "Channel Tunnel Oral Answers to Questions: Transport, House of Commons debates". theyworkforyou dot com. 23 April 1990.

- ↑ "Eastern approach". New Civil Engineer. 23 March 2000. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- ↑ "The Channel Tunnel Rail Link: Report by the Controller and Auditor General". National Audit Office. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- ↑ "Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions: The Channel Tunnel Rail Link" (Press release). National Audit Office. 28 March 2001. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- ↑ "About St Pancras". HS 1 Limited. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- ↑ Harper, Keith (30 May 2000). "Railtrack funding of Channel rail link in doubt again". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- ↑ Harrison, Michael (16 January 2001). "Railtrack could ditch new Channel rail link". The Independent. London. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- ↑ Brown, Colin (1 April 2001). "Railtrack to lose its new-line monopoly". The Independent. London. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- ↑ Harrison, Michael (17 January 2001). "Phase two of tunnel link need not be built by Railtrack, says Eurostar". The Independent. London. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- ↑ Walters, Joanna (21 October 2001). "Rail's shattered dream". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- ↑ "Railtrack Sells Part of Channel Tunnel Rail Link". Daily Mail. London. 3 April 2003. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- ↑ Boles, Tracey (19 February 2006). "City grandee tries to grab tunnel link firm". The Sunday Times. London. Retrieved 15 November 2006.(subscription required)

- 1 2 "LCR rejects takeover bid". RailwayPeople. Ashby-de-la-Zouch. 31 March 2006. Retrieved 15 November 2006.

- ↑ Clark, Andrew; Seager, Ashley (21 February 2006). "Debt-laden Channel tunnel rail link is 'nationalised'". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 15 November 2006.

- ↑ Owen, Ed (8 June 2009). "Government takes control of London and Continental". New Civil Engineer. London. Retrieved 16 February 2010.

- 1 2 "HS1 concession sold". Modern Railways. London. December 2010. p. 6.

- ↑ "British state assets selloff". The Straits Times. Singapore. 12 October 2009. Archived from the original on 15 October 2009. Retrieved 12 October 2009.

- ↑ "As high speed rail is being dropped in California and France, it's time for Britain to take the hint". The Spectator.

- ↑ Roberts (29 October 2007). "TOC and FOC aspirations for a 7 day railway". Seven Day Railway (Supporting document). Network Rail October 2007 Strategic Business Plan (Report). Retrieved 25 May 2012.

"7 day railway will operate on new high speed line. Inspections carried out during daytime white period & maintenance done at night.

- ↑ "High speed preview services announced". 1 June 2009. Archived from the original on 12 June 2009. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

Daylight HS1 track inspection... Currently track engineers inspect high speed infrastructure during daylight hours.

- 1 2 sxmarcel (17 November 2008). "Possessions allowance" (PDF). Second Consultation on Prospective Levels and Principles of Track Access Charging for the High Speed 1 Railway. p. 6,21. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ↑ Coart, François (5 July 2011). "HS1 Ltd Freight Avoidable Costs Review" (letter). p. 1. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ↑ "Eurostar breaks high speed record". Erik's Rail News. 30 July 2003. Retrieved 12 April 2007.

- ↑ "Engineer electrocuted on rail link". BBC News. 30 March 2003. Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- 1 2 "Firms fined over rail link death". BBC News. 4 October 2004. Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- ↑ "Man killed in rail tunnel blaze". BBC News. 17 August 2005. Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- ↑ "Channel Tunnel burns victim dies". BBC News. 21 August 2005. Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- ↑ "Case study: Channel Tunnel Rail Link". New Civil Engineer. London. 22 February 2001. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- 1 2 "Eurostar celebrates 10 years at Ashford International" (Press release). Eurostar. 9 January 2006.

- ↑ "Depot mark 2 promises faster maintenance of faster trains". Railway Gazette International. 31 October 2007.

- ↑ "Railway Herald on-line magazine, Issue 75" (PDF). 9 March 2007. p. 3. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- ↑ "Ebbsfleet open to Eurostar trains". BBC News. 19 November 2007. Retrieved 5 July 2009.

- ↑ "RailEurope". save-eurostar.org. Retrieved 14 May 2009.

- ↑ "New station means Eurostar change". BBC News. 12 September 2006. Retrieved 14 December 2007.

- ↑ "Save Ashford International (retrieved from archive.org)". saveashfordinternational.org.uk. Archived from the original on 12 April 2008. Retrieved 18 February 2008.

- 1 2 "High speed timetable". Southeastern Railways. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ↑ Official name of the station according to the Department of Transport, released in response to a Freedom of Information Act request at Whatdotheyknow.com. Retrieved 2 December 2008.

- ↑ Official name of the station according to the London Borough of Camden released in response to a Freedom of Information Act request at Whatdotheyknow.com. Retrieved 2 December 2008.

- ↑ Lydall, Ross (7 March 2006). "Security at heart of St Pancras revamp". London Evening Standard.

- ↑ "From concept to reality". Modern Railways. London: Ian Allan. November 2007. p. 51.

- ↑ Wolmar, Christian (31 August 1994). "Channel rail link to get one station". The Independent. London. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- ↑ "Southeastern Highspeed". Southeastern. 1 December 2009. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ↑ "Docklands Light Railway extension marks one year to go to the London 2012 Paralympic Games" (Press release). Retrieved 31 August 2011.

- ↑ Clark, Andrew (17 February 2005). "Decision makers go underground to ride the route of new rail link". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- ↑ "High Speed 1 security". Railway Strategies. Schofield Publishing. 1 January 2009.

- ↑ "07 099 DGN certificate" (Certificate of Derogation from a Railway Group Standard). Rail Safety and Standards Board. 24 August 2007. p. 2. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

The new CTRL St Pancras terminal station and approaches is fitted with colour light signalling. In addition, the continuous supervision KVB Automatic Train Protection (ATP) system is installed to comply with CTRL requirements for full ATP.

- ↑ "Britain finally joins the high-speed club: the first section of CTRL opens on 28 September". International Railway Journal. August 2003.

Certification of the TVM430 signalling system on the CTRL almost caused a delay in opening of section 1 in 2003.

- ↑ "Strategic Freight Network: The Longer-Term Vision" (PDF). Department for Transport. p. 15. Retrieved 17 May 2009.

20.5 European freight link (UIC GB+ Gauge): A European loading gauge freight link has been secured as far as Barking through Channel Tunnel

- ↑ "Eurostar Revamps High-Speed Service". 15 October 2007. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- ↑ "Britons protest tunnel rail routes". St. Petersburg Times. 27 February 1989.

- ↑ Tully, Shawn (20 November 1989). "Full Throttle towards a new era". CNN.

To put some steel into 1992, the Europeans are building a network of tunnels, bridges, and high speed railways

- ↑ "Section 2 Major Contracts – Descriptions" (PDF). High Speed 1. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- ↑ "The regeneration benefits of the CTRL". Department for Transport. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- ↑ Griffiths, Emma (5 August 2005). "Developers see London's eastern promise". BBC News. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- ↑ "Final phase of Channel Tunnel Rail Link will be major regeneration boost – Prescott" (Press release). London and Continental Railways. 3 April 2001. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- ↑ Plowden, Stephen (2 April 2001). "Special Report – Coming soon: the Dome on wheels". New Statesman. London. Archived from the original on 27 December 2006.

- ↑ Glancey, Jonathan (27 May 2005). "Tunnel vision". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

Somers Town, on one side of St Pancras, remains little more than a slum, while King's Cross is still an unzipping ground for low-rent prostitution, a crack needle in the side of civilised London.

- ↑ Webster, Ben (14 November 2007). "Five Waterloo platforms left in limbo by Eurostar pullout". The Times. London. Retrieved 2 May 2009.

- ↑ Higham, Nick (6 November 2007). "The transformation of St Pancras". BBC News. Retrieved 14 December 2007.

- ↑ Millward, David (3 November 2007). "Eurostar will cross London — in 15 hours". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 16 April 2009.

- ↑ Middleton, Peter (Producer) (2009). Eurostar: Brussels-Midi to London St Pancras International (DVD). Video 125 Ltd. Event occurs at 1hr 29min 35sec. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ High Speed 1, United Kingdom, Railway Technology

- ↑ Timetable Core destinations 15 December 2013 to 24 May 2014, Eurostar.

- ↑ "Kent Route Utilisation Strategy" (PDF). Network Rail. January 2010. p. 8.

- ↑ Transport Plan for the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games: Consultation report (PDF). Olympic Delivery Authority. October 2007. p. 94. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- ↑ "Channel Tunnel Rail Link opens for freight services" (Press release). English, Welsh and Scottish Railway. 2 April 2004. Archived from the original on 1 October 2006. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- ↑ Firzli, M. Nicolas J. (2013). "Transportation Infrastructure and Country Attractiveness". Revue Analyse Financière. Paris. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ↑ "High Speed One – What we do", highspeed1.co.uk, HS1 Limited, retrieved 29 August 2011

- ↑ "High Speed One". HS1 Ltd. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- ↑ Stretton, Andrew G.W. (3 August 2010). "Exemption from the Fitment of an Automatic Train Protection System for Certain Types of Train on Network Rail (High Speed) Ltd Controlled Infrastructure" (covering letter). Railway Safety Regulations 1999. Understanding the Meaning of Test Trains. Office of Rail Regulation. p. 3. Retrieved 16 January 2010.

... is controlled by Network Rail (High Speed) Ltd who, as infrastructure manager ...

- ↑ Annual Report and Accounts (PDF) (Report). Network Rail Infrastructure Limited. 2004. p. 39.

- ↑ Deputy Chief Inspector of Railways (4 June 2010). "Infrastructure Controller: Network Rail (High Speed) Ltd" (Certificate of Exemption). Office of Rail Regulation. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

Network Rail (High Speed) is exempt … in relation to the operation on the Channel Tunnel Rail Link of the following classes of trains: ...

- ↑ Deputy Director of Railway Safety (8 February 2010). "Train Operators Certificate" (Certificate of Exemption). Office of Rail Regulation. p. 1. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- ↑ Milner, Chris (2 June 2011). "TGV in secret visit to UK". The Railway Magazine. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- ↑ "United Kingdom: Track Geometry Checks". SNCF International. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

SNCF International … with Eurotunnel and .. Network-Rail (High Speed) are … carrying out Eurotunnel monitoring runs using the Iris 320 train and extending them as far as London St Pancras.

- ↑ "Maintenance". Inspecting the infrastructure at 100 km/h (PDF). Annual Report (Report). Eurotunnel Group. 2010. p. 24. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

IRIS 320 measuring train … since December 2010, … inspecting the Channel Tunnel, pulled by a Eurotunnel diesel locomotive at 100 km/h (62 mph) … every two months

- ↑ "Overdue U.K. 'Bullet Train' Enters Service Amid Cuts". Bloomberg News. New York. 29 June 2009. Retrieved 5 July 2009.

- ↑ Rudd, Matt (28 October 2007). "Eurostar to Brussels". The Sunday Times. London. Retrieved 10 May 2009.

- ↑ "Eurostar Destinations". Eurostar. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- ↑ "Our history". Eurotunnel. Archived from the original on 23 November 2010. Retrieved 10 May 2009.

- ↑ Waterloo Sunset. YouTube. 20 December 2007.

- ↑ "Eurostar breaks UK high speed record" (Press release). Eurostar. 30 July 2003. Retrieved 6 July 2009.

- ↑ "Official Eurostar video of Record-breaking High Speed 1 run from Paris to London". Eurostar. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ↑ "London and Continental Railways Limited" (Press release). Department for Transport. 8 June 2009.

- ↑ "Eurostar set Paris-London record". BBC News. 4 September 2007. Retrieved 4 September 2007.

- ↑ Malkin, Bonnie (20 September 2007). "Eurostar sets new record from Brussels". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- ↑ Booth, Jenny (27 October 2004). "Britain is to have its own bullet trains". The Times. London. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- ↑ "South Eastern High Speed Timetable". Southeastern. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ↑ "South Eastern Mainline 4 Times". Southeastern. 11 May 2009. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ↑ "Full speed ahead at St Pancras International Station". London2012 blog. 8 November 2007. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

- ↑ Andrews, Emily (12 September 2009). "British bullet train will hit 140 mph (225 km/h) (but only when it's late)". Daily Mail. London.

- ↑ Hale, Beth (23 June 2009). "The British Bullet: 140 mph (225 km/h) train unveiled... but passengers will pay for slashed commuter times with fare hikes". Daily Mail. London.

Although slower than the 186 mph (299 km/h) Eurostar trains that share the same line, the Class 395 train is lighter and accelerates faster than its French-built counterpart

- ↑ "Southeastern: Highspeed services reach Ramsgate and Dover" (Press release). Southeastern. 13 August 2009. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ↑ "High-speed trains start from Maidstone". Kent Messenger. Maidstone. 20 May 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- ↑ "Transportation and Logistics in the DB Group". DB Schenker. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ↑ "Eurostar Revamps High-Speed Service". Railway Technology. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ↑ "Freight trains to use High Speed 1 from 2010". Railway Gazette International. 16 April 2009. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ↑ "DB Schenker Rail operates first freight train over High Speed 1" (Press release). DB Schenker Rail (UK). 27 May 2011. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- ↑ "First freight on High Speed 1". Railway Gazette International. London. 29 May 2011. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ↑ "DB Schenker to upgrade locomotives for High Speed 1 service". Railway Technology.com. 12 December 2011. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ↑ Class 92 09/11/12 – wnxx.com (Retrieved 8 January 2013)

- ↑ Murray, Dick (1 November 2007). "Germans plan Eurostar rival". London Evening Standard. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ↑ Wolmar, Christian (23 November 2007). "Who is going to use the new high speed line?". Rail (579). Peterborough. Retrieved 11 May 2009.

- ↑ Murray, Dick (19 December 2007). "German rival for Eurostar". London Evening Standard. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ↑ Webster, Ben (12 December 2008). "We'll buy UK's share of Eurostar — and run it better, say Germans". The Times. London. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ↑ O'Connell, Dominic (13 March 2008). "Fees for high-speed tunnel link derail Eurostar's gravy train". The Times. London. Retrieved 29 May 2009.

- ↑ London & Continental Railways – scroll down to section "About the future".

- ↑ Barrow, Keith (1 April 2009). "2010: A high-speed odyssey". International Railway Journal. London. Retrieved 11 May 2009.

- ↑ "Chemins de fer: le ton monte entre Deutsche Bahn et la SNCF". Le Point (in French). Paris. Agence France-Presse. 16 December 2008. Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- ↑ "Deutsche Bahn gets access to Channel Tunnel". Berlin: Deutsche Welle. 16 December 2009. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

- ↑ Lydall, Ross (3 February 2010). "The train at St Pancras will be departing for … Germany via Channel Tunnel". London Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 6 February 2010. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ↑ Jameson, Angela (10 March 2010). "Deutsche Bahn may run London to Frankfurt service". The Times. London. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- 1 2 Scott, Richard (19 October 2010). "German rail firm DB competes for Channel Tunnel routes". London: BBC News. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ↑ "Deutsche Bahn to run ICE3 to Britain this year". Railway Gazette International. London. 29 July 2010.

- ↑ "ERA Channel Tunnel report is a welcome first step for Deutsche Bahn's high speed ICE services to London" (Press release). Deutsche Bahn. 22 March 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ↑ "Deutsche Bahn to start commercial services from London in 2013" (PDF). Railway Herald, Issue 285 page 9. 26 September 2011. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- ↑ "Channel Tunnel". Business Traveller. 19 February 2014. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ↑ "International Rail Services". HS1 Ltd. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ↑ Allen, Peter (10 September 2008). "Airlines plot Eurostar rival services". London Evening Standard. Retrieved 11 September 2008.

- ↑ Savage, Michael (11 September 2008). "Air France to launch 'quicker' train to Paris as Eurostar monopoly ends". The Independent. London. Retrieved 11 May 2009.

- ↑ "Veoila and Trenitalia mount rival Eurostar service", Breaking Travel News, 24 December 2009.

- ↑ "Eurostar Failures Bolster Deutsche Bahn's Tunnel Bid (Update2)". Bloomberg. New York. 9 March 2010. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

Renfe said … it's looking for opportunities to expand … through the [Channel] tunnel.

- ↑ Keeley, Graham (27 November 2009). "Rail offers London to Madrid in eight hours". The Times. London. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ↑ Allen, Peter (5 February 2010). "Commuter trains from Calais to Kent 'could be running before 2012 Olympics', claims French mayor". Daily Mail. London. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

Bibliography

- Young, George; Alison Gorlov (1995). Channel Tunnel Rail Link. Union Railways.

- National Audit Office (2001). Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions: The Channel Tunnel Rail Link. The Stationery Office. ISBN 0-10-286801-8.

- National Audit Office (2005). Progress on the Channel Tunnel Rail Link. The Stationery Office. ISBN 0-10-293343-X.

- Montagu, Samuel; Department of Transport (1993). Channel Tunnel Rail Link. HMSO.

- Bertolini, Luca; Tejo Spit (1998). Cities on rails: the redevelopment of railway station areas. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-419-22760-1.

Further reading

- Pielow, Simon (1997). Eurostar. Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-2451-0.

- Anderson, Graham; Roskrow, Ben (1994). The Channel Tunnel Story. London: E & F N Spon. ISBN 0-419-19620-X.

- European Commission Directorate-General for Regional Policy and Cohesion (1996). The regional impact of the Channel Tunnel throughout the Community. Luxembourg: European Commission. ISBN 92-826-8804-6.

- Sievert, Terri (2002). The World's Fastest Trains. Capstone Press. ISBN 0-7368-1061-7.

- Griffiths, Jeanne (1995). London to Paris in Ten Minutes: The Eurostar Story. Images. ISBN 1-897817-47-9.

- Comfort, Nicholas (2007). The Channel Tunnel and its High Speed Links. Oakwood Press. ISBN 1-56554-854-X.

- Parliament: House of Commons Transport Committee (2008). Delivering a Sustainable Railway. The Stationery Office. ISBN 0-215-52222-2.

- Mitchell, Vic (1996). Ashford: From Steam to Eurostar. Middleton Press. ISBN 1-873793-67-7.

- "Channel Tunnel route and terminals: BR reveals the possibilities". RAIL. No. 84. EMAP National Publications. September 1988. p. 7. ISSN 0953-4563. OCLC 49953699.

- "Preferred bidders announced for Channel Tunnel Rail Link contracts". RAIL. No. 323. EMAP Apex Publications. 28 January – 10 February 1998. pp. 10–11. ISSN 0953-4563. OCLC 49953699.

- "Prescott starts CTRL construction - the first new main line in 99 years". RAIL. No. 342. EMAP Apex Publications. 21 October – 3 November 1998. p. 15. ISSN 0953-4563. OCLC 49953699.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to High Speed 1. |

- Highspeed 1 Website

- Trade article

- Marco Polo Excite (European X-Channel Intermodal Transport Enhancement)