Guerrilla Girls

| Motto | Reinventing the "F" word: feminism! |

|---|---|

| Formation | 1985 |

| Headquarters | New York, New York, United States |

Region served | Worldwide |

Official language | English |

| Website |

guerrillagirls |

Guerrilla Girls are an anonymous group of feminist, female artists devoted to fighting sexism and racism within the art world. The group formed in New York City in 1985 with the mission of bringing gender and racial inequality in the fine arts into focus within the greater community. Members are known for the gorilla masks they wear to remain anonymous. They wear the masks to conceal their identity because they believe that their identity is not what matters as GG1 explains in an interview "...mainly, we wanted the focus to be on the issues, not on our personalities or our own work."[1]

History

Guerrilla Girls were formed by seven women artists in the spring of 1985 in response to the Museum of Modern Art's exhibition "An International Survey of Recent Painting and Sculpture," which opened in 1984. The exhibition was the inaugural show in the MoMA's newly renovated and expanded building, and was planned to be a survey of the most important contemporary art and artists in the world.[2]

In total, the show featured works by 169 artists, of whom only 13 were female. Guerrilla Girls claimed that a comment by the show's curator, Kynaston McShine, further highlighted the gendered bias of the exhibition and of MoMA as an institution: "Kynaston McShine gave interviews saying that any artist who wasn’t in the show should rethink ‘his’ career."[3] In reaction to the exhibition and the prejudice McShine displayed, they decided to protest in front of the museum. Thus, the Guerrilla Girls were born.

The protests yielded little success, however, so the Guerrilla Girls embarked upon a postering campaign throughout New York City, particularly in the SoHo and East Village neighborhoods.[4]

Once better established, the group also started taking note of racism within the art world, incorporating artists of color into their fold. They also began working on projects outside of New York, commenting on sexism and racism nationally and internationally. Though the art world has remained the group's main focus, challenging sexism and racism in films, mass and popular culture, and politics has also been part of the Guerrilla Girls' agenda. Tokenism also represents a major group concern.[4]

When asked about the masks, the girls answer "We were Guerrillas before we were Gorillas. From the beginning the press wanted publicity photos. We needed a disguise. No one remembers, for sure, how we got our fur, but one story is that at an early meeting, an original girl, a bad speller, wrote 'Gorilla' instead of 'Guerrilla.' It was an enlightened mistake. It gave us our 'mask-ulinity.'".[5] In an interview with New York Times the Girls were quoted, "Anonymous free speech is protected by the Constitution. You'd be surprised what comes out of your mouth when you wear a mask." [6]

In 2015, marking the 30th anniversary of the Guerrilla Girls creation, Matadero Madrid hosted an exhibition that included most of the collective's production and organized a series of events including a talk/performance by two of the Guerilla Girls under the pseudonyms of "Frida Khalo" and "Kathe Kollwitz".[7][8] The exhibition also showed the 1992 documentary "Guerrilla in Our Midst" by Amy Harrison.[9]

Influence

Many Feminist artists in the 1970s dared to imagine that female artists should produce authentically and radically different art, undoing the prevailing visual paradigm. Also in the 1970s a pioneering feminist critic, Lucy Lippard, began curating all-women art shows to protest what she saw as the deeply flawed approach of merely assimilating women into the prevailing art system.[10] The Guerrilla Girls were mostly shaped by the 1970s women’s movement, yet resolved to devise new methods. They noticed a decline in the tactics of the 1970s feminist campaigns, such as the ineffectual picket line the Women’s Caucus for Art had mustered at MoMa. "We had to have a new image and a new kind of language to appeal to a younger generation of women," recalls one of the founding Guerrilla Girls, who used the alias “Liubov Popova.” [11] Guerrilla Girls responded to the claims that the 1970s Feminist movements were man-hating, anti-maternal, strident, and humorless:[10] They adopted a poststructuralist theory, thereby learning from the 1970s initiatives, but with a different language and style. The 1970s feminists were tackling grim and unfunny issues such as sexual violence, hence the Guerrilla Girls, in order to combat the public backlash and to keep their spirits intact, approached their work with wit and laughter.[10]

Criticism

Race

While often advocating for art institutions to display more artists of color, the Guerrilla Girls are not immune to perpetuating white supremacy in their own collective. The Guerrilla Girls potentially do not meet the demands for racial diversity they make of art institutions in their own organization, for, as former Guerrilla Girl “Zora Neale Hurston” explains, the membership of the Guerrilla Girls “was mostly white” and largely mirrored the demographics of the art world they critiqued.[12] The founders of the group are all white, and the de facto leadership of the Guerrilla Girls in recent years, "Frida Kahlo" and "Kathe Kollwitz," are both white.[10] (“Frida Kahlo” has also been criticized for her appropriation of a Latina artist’s name.)[13] However, any precise information on the demographics of the Guerrilla Girls is impossible, for they have “staunchly, and problematically, resisted being surveyed as to the makeup of their own membership."[10]

Those people of color who have been a part of the Guerrilla Girls have faced numerous challenges by being part of the organization. Tokenism, silencing, disrespect, and whitewashing have driven many artists of color away from the Guerrilla Girls.[10][12] “Alma Thomas” describes being uncomfortable, as a black woman, with wearing the Guerrilla Girls’ signature gorilla masks.[14] Little effort was devoted to understanding the challenges of artists of color; “their whiteness was such that they…. didn't understand that blacks were being put in a completely separate world in the art world, that black male artists and black female artists are completely separated, completely segregated to this day."[12] Ultimately, this widespread antagonism has led to many “artists of color who… left after a few meetings because they could sense the unspoken hierarchy in the group."[15]

Second-Wave Feminism and Essentialism

Having been created in the 80’s, it is not surprising that the Guerrilla Girls largely adopted the feminist ideologies of their time. The Guerrilla Girls emerged at the tail end of the second-wave feminist movement, and thus had to navigate the differences between established and emerging feminist theory. “Alma Thomas” describes this grey-area the Guerrilla Girls occupied as “universalist feminism,” bordering on essentialism.[14] Anna Chave claims the Guerrilla Girls’ essentialism was much more profound, leading the group to be “assailed by… a rising generation of women wise in the ways of poststructuralist theory, for [their] putative naiveté and susceptibility to essentialism."[10] This essentialism may be most clearly exhibited in two pieces by the Guerrilla Girls: their 1998 book The Guerrilla Girls Bedside Companion to the History of Western Art and their piece The Estrogen Bomb (2003–13). In regards to the former, “Alma Thomas” explains that “[The Guerrilla Girls Bedside Companion to the History of Western Art] was so embedded in that second-wave feminist and even pre-second-wave essentialism.”[14] Critiques of The Estrogen Bomb for being transmisogynistic have recently been voiced anonymously by students at Minneapolis College of Art and Design.[16][17] Aside from essentialism, the Guerrilla Girls have also been critiqued for failing to integrate intersectionality into their work.[13] However, it is worth noting that the beliefs of the Guerrilla Girls are not monolithic, and individual members have many different understandings of feminism.[14]

Internal Disputes

Leading up to their 2003 lawsuit, “Frida Kahlo” and “Kathe Kollwitz” faced growing animosity from other members of the Guerrilla Girls. Despite intentions for a non-hierarchal, equitable power structure, in the late ‘90s it developed that in the day-to-day work of the Guerrilla Girls, “there were two people who were going to make the final decisions no matter what you said."[12] The authoritarian rule of “Kahlo” and “Kollwitz’” was most evident in the publishing of the Guerrilla Girls’ second book, The Guerrilla Girls Bedside Companion to the History of Western Art. “Kahlo” and “Kollwitz” controlled completely the direction of the book, and, despite using material created collectively by the Guerrilla Girls, claimed credit for the book and took all of the profits made off it. Other members condemned the book as “undemocratic and… against the spirit of the [Guerrilla] Girls."[14]

Eventually, this uneven power structure led five Guerrilla Girls to be “fired” from the collective. (These members went on to form Guerrilla Girls BroadBand.) At the same time, “Kahlo” and “Kollwitz” were in the process of trademarking the name “Guerrilla Girls,” leading to them filing a lawsuit in 2003 against both Guerrilla Girls BroadBand and Guerrilla Girls On Tour! for infringing upon their trademark.[15] This move prompted fire from many current and former Guerrilla Girls, who objected to the attempts of “Kahlo” and “Kollwitz” to claim responsibility for the creation of a collective effort, as well as the flippancy with which the two members discarded their anonymity in the course of the lawsuit.[10]

Selling-out

Upon their debut in 1985, the Guerrilla Girls began to be praised by the same art world they critiqued.[18] Since then, this dynamic has only intensified, with the Guerrilla Girls staging cooperative exhibitions with museums and allowing their work to be kept by hegemonic institutions. This has led some to question the efficacy, if not the hypocrisy, of the group working within the same structures they critique.[13][18]

Current status

Since 1985, the Guerrilla Girls have witnessed some positive changes within the art world, including an increased awareness of sexism, and more accountability on the part of curators, art dealers, collectors and critics.[19] The group is credited, above all, with sparking dialogue and bringing national and international attention to issues of sexism and racism within the arts.

In 2001, the Guerrilla Girls split into three groups: Guerrilla Girls, Inc., Guerrilla Girls BroadBand, and a touring theater group, Guerrilla Girls On Tour!. In 2003, Guerrilla Girls, Inc. filed a lawsuit against Guerrilla Girls BroadBand and Guerrilla Girls On Tour for copyright and trademark infringement.[20]

Lawsuit

As the Guerilla Girls dominion began to grow, tension began causing what the Girls referred to as a "banana split" in the group. One branch was called the Guerrilla Girls on Tour, which focused on the discrimination in theatre. In October 2003, on behalf of Guerilla Girls, Inc., two girls of the original group "Frida Kahlo" and "Kathe Kollwitz", filed a federal lawsuit against Guerrilla Girls on Tour. Although their former colleague "Gertrude Stein" was in the on-tour group, Kahlo and Kollwitz were charging them, among other things, with copyright and trademark infringement and unjust enrichment. What caused an uproar within the group was that Frida Kahlo and Kathe Kollwitz chose to identify and reveal themselves as Jerilea Zempel and Erika Rothenberg, respectively.[20]

However, Judge Louis L. Stanton handled the case and rejected the "bizarre" suggestion of the defendants’ to be allowed to testify in his courtroom while wearing their gorilla masks. He also stated that "Mundane court procedures for adjudicating legal rights and the ownership of property require direct and cross-examination of real persons with real addressed and attributes."[20]

Zempel and Rothenberg wrote in their forty-five paged complaint that they were "guiding forces" behind the Guerrilla Girls and "the group was informally organized, (and) had no official hierarchy." They wanted the court to stop the broadband enterprise from using the name Guerrilla Girls and are seeking what could be millions of dollars in damages. In 2006, there was a settlement that the theatre group would represent itself specifically as the Guerrilla Girls on Tour.

Activity

Guerrilla Girls organize protests, create posters, stickers, billboards and artwork, present at public speaking engagements and research into the unfair conditions of working women artists and artists of color.[4]

Early organizing was based around meetings where the group would evaluate the statistical data they gathered regarding gender inequality within the New York City's art scene. The Guerrilla Girls also worked closely with artists, encouraging them to speak to those within the community to bridge the gender gap where they perceived it.[21]

Notably, during the first years after its founding, the Guerrilla Girls started conducting "weenie counts," where members would go to institutions, like the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and count the male to female subject ratio in artworks. The data gathered from the Met's public collections in 1989 showed that in the Modern Art sections less than 5% of the works were by female artists, while 85% of the nudes were female.

The Guerrilla Girls have since done research into sexism and created artworks at the request of various people and institutions, among others, the Istanbul Modern, Istanbul, Witte de With Center for Contemporary Arts, Rotterdam and Fundación Bilbao Arte Fundazioa, Bilbao. They have also partnered with Amnesty International, contributing pieces to a show under the organization's "Protect the Human" initiative.[22]

In recognition of their work, the Guerrilla Girls have been invited to give talks at world-renowned museums, including a presentation at the MoMA's 2007 "Feminist Futures" Symposium. They have also been invited to speak at art schools and universities across the globe, and gave a 2010 commencement speech at the School of the Arts Institute Chicago.

Protest art

Throughout their existence the Guerrilla Girls have gained the most attention for their bold protest art.

Their works, mainly posters, are used to express their ideals, opinions and concerns with regard to a variety of social topics. The Guerrilla Girls' art has always been fact-driven, and informed by the group's data collection and so-called "weenie counts." However, to be more inclusive and to make their posters more eye-catching, the Guerrilla Girls pair facts with humorous images: "We use facts, humor and outrageous visuals to expose sexism, racism and corruption in politics, art, film and pop culture."[23] The group were also activists for equal representation of women in institutional art, and highlighted artist Louise Bourgeois in their "Advantages to Being a Women artist," poster in 1988 as one line read, "Knowing your career might not pick up till after you're 80."[24] Their pieces are also notable for their use of combative statements such as '"When racism and sexism are no longer fashionable, what will your art collection be worth?"[4]

In the early days, posters were brainstormed, designed and then hung around New York City. Small handbills based on their designs were also passed out at events by the thousands.[21] The first posters were mainly black and white fact-sheets, highlighting inequalities between male and female artists with regard to number of exhibitions, gallery representation and pay. The posters also intended to reveal how sexist the art world was in comparison to other industries and to national averages. For example, in 1985 they printed a poster showing that the salary gap between men and women in the art world was starker than the United States' average, proclaiming "Women in America earn only 2/3 of what men do. Women artists earn only 1/3 of what men do."

These early posters also often targeted specific galleries and artists. Another 1985 poster listed the names of some of the most famous working artists, such as Bruce Nauman and Richard Serra, and asked What do these artists have in common? with the answer they allow their work to be shown in galleries that show no more than 10% of women or none at all.

The posters were rude; they named names and they printed statistics (and almost always cited the source of those statistics at the bottom, making them difficult to dismiss). They embarrassed people. In other words, they worked.[25]

The Guerrilla Girls' first color poster, which remains the group's most iconic image, is the 1989 Metropolitan Museum poster, which used data from the group's first "weenie count." In response to the overwhelming amount of female nudes counted in the Modern Art sections, the poster asks, sarcastically, "Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum?". Next to the text is an image of the Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres painting La Grande Odalisque, one of the most famous female nudes in Western art history, with a gorilla head placed over the original face.

In 1990, the group designed a billboard featuring the Mona Lisa that was placed along the West Side Highway supported by the New York City public art fund. For one day, New York's MTA Bus Company also displayed bus advertisements with Met. Museum poster. Stickers also became popular calling cards representative of the group. In the mid-1980s they infiltrated, without masks to maintain anonymity, the Guggenheim Museum bathrooms, placing stickers they had created about female inequality on the walls.[21]

In 1998, Guerrilla Girls West protested at the San Jose Museum of Art, over low representation of women artists.[26]

Since 2002, Guerrilla Girls, Inc. have designed and installed billboards in Los Angeles during the Oscars to expose white male dominance in the film industry, such as: "Anatomically Correct Oscars," "Even the Senate is More Progressive than Hollywood," "The Birth of Feminism,"[27] "Unchain the Women Directors."[28] In 2005, the group created large-format posters and an installation at the Venice Biennale. The 2005 Biennale was the first in 110 years to be overseen by women.[29]

Though the Guerrilla Girls' protest art directed at the art world remains their most well-known work, throughout their existence the group has also periodically created pieces attacking politicians, specifically conservative Republicans. Those criticized have included George Bush, Newt Gingrich and most recently Michele Bachmann.

Many major museums criticized by the Guerrilla Girls, such as the MoMA and Tate Modern, now own works by the group in their collection.

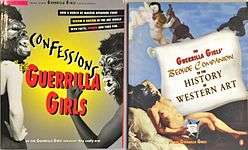

Publications

Guerrilla Girls have also published several books on the subject of inequality in the art world. In 1995 they published their first book: Confessions of the Guerrilla Girls. In 1998 which contained an analysis and compilation of their work. They also published The Guerrilla Girls Bedside Companion to History of Western Art , which was a consciousness-raising comic book for people who have never noticed that women in European Art always appeared naked. Then in 2003 the book Bitches, Bimbos and Ballbreakers was published, examining "The Top Stereotypes from Cradle to Grave," with thumbnail histories for cultural clichés ranging from "Daddy's Girl" and "the Girl Next Door" to "the Bimbo/Dumb Blonde" and "the Bitch /Ballbreaker", each given "the trademark Guerrilla Girl treatment: pointed factoids and cool graphics."[30] The 2004 book The Guerrilla Girl’s Museum Activity Book (with an updated edition from 2012) is a parody of a children's museum activity book, with each the activities meant to reveal a problematic aspect of museum culture and major museum collections. A book on the subject of hysteria, "The Hysterical Herstory Of Hysteria And How It Was Cured From Ancient Times" Until Now" was published as a pdf file in 2009.[31]

Members and names

Membership in the New York City group is by invitation only, based on relationships with current and past members, and one's involvement in the contemporary art world. A mentoring program was formed within the group, pairing a new member with an experienced Guerrilla Girl to bring them into the fold. Due to the lack of formality, the group is comfortable with individuals outside of their base claiming to be Guerrilla Girls; Guerrilla Girl 1 stated in a 2007 interview: "It can only enhance us by having people of power who have been given credit for being a Girl, even if they were never a Girl." Men are not allowed to become Guerrilla Girls, but may support the group by assisting in promotional activities.[21]

Guerrilla Girls names are pseudonyms generally based on dead female artists. Members goes by names such as Kathe Kollwitz, Alma Thomas, Rosalba Carriera, Frida Kahlo, Julia de Burgos, and Hannah Höch. Guerrilla Girls' "Carriera" is credited with the idea of using pseudonyms as ways to not forget female artists. Having read about Rosalba Carriera in a footnote of Letters on Cézanne by Rainer Maria Rilke, she decided to pay tribute to the little-known female artist with her name. This also helped to solve the problem of media interviews; the group was often interviewed by phone and would not give names, causing problems and confusion amongst the group and the media. Guerrilla Girl 1 joined in the late 1980s, taking on her name as a way to memorialize women in the art community who have fallen under the radar and did not make as notable as an impact as the names takes on by other members.[21]

Gorilla symbolism

The idea to adopt the gorilla as the group's symbol stemmed from a spelling error. One of the first Guerrilla Girls accidentally spelled the group's name at a meeting as "gorilla."[19] Despite the fact that the idea of using a gorilla as group symbol might have been accidental, the choice is nevertheless pertinent to the group's overall message in several key ways.

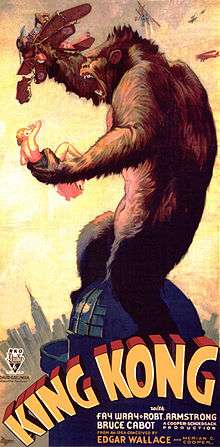

To begin with, the gorilla in popular culture and media is often associated with King Kong, or other images of trapped and tamed apes. In the 2010 SAIC Commencement, the comparison between institutionalized artists and tamed apes was explicitly made:

And last, but not least, be a great ape. In 1917, Franz Kafka wrote a short story titled A Report to An Academy, in which an ape spoke about what it was like to be taken into captivity by a bunch of educated, intellectual types. The published story ends with the ape tamed and broken by the stultified academics. But in an earlier draft, Kafka tells a different story. The ape ends his report by instructing other apes NOT to allow themselves to be tamed. He says instead: break the bars of your cages, bite a hole through them, squeeze through an opening…and ask yourself where do YOU want to go [32]

The gorilla is also typically associated with masculinity. The Met. Museum poster is in part shocking because of its juxtaposition of the eroticized female odalisque body, and the large, snarling gorilla head. The addition of the head detracts from the male gaze and changes the way in which viewers are able to look at or understand the highly sexualized image. Further, the addition of the gorilla questions and modifies stereotypical notions of female beauty within Western art and popular culture, another stated goal of the Guerrilla Girls.

Guerrilla Girls, who wear the masks of big, hairy, powerful jungle creatures whose beauty is hardly conventional […] believe all animals, large and small, are beautiful in their own way.[33]

Though this goal has never been explicitly stated by the group, it is also helpful to note that in the history of Western art primates have often been associated with the visual arts, and with the figure of the artist. The idea of ars simia naturae ("art the ape of nature") maintains that the job of art is to "ape", or faithfully copy and represent, nature. This was an idea fist popularized by Renaissance thinker Giovanni Boccaccio who alleged that "the artist in imitating nature only follows Nature's own command."[34] The Guerrilla Girls' critique of art institutions mainly centers on the fact that there are fewer female subjects and artists represented in major art collections, a fact which is not at all reflective of the world's overall population. Ignoring women artists or artists of color cannot be seen as ars simia naturae, a fact that the ape image, whether intentionally or not, calls attention to.

Notable collections

- Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois[35]

- Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York[4]

- Tate, United Kingdom[36]

- Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota[37]

- Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, New York[38]

Notable exhibitions

- The Night the Palladium Apologized, 1985, Palladium, New York, New York

- Guerrilla Girls Review the Whitney, 1987, The Clocktower, New York, New York[21]

- Guerrilla Girls Printed Matter, 1995, 77 Wooster Street, SoHo [39]

- Guerrilla Girls: Exposición Retrospectiva, 2013, Alhóndiga Bilbao, Bilbao, Spain[40]

- Media Networks: Andy Warhol and the Guerrilla Girls, (display), 2016, Tate Modern, London, United Kingdom[41]

- Guerrilla Girls: Not Ready to Make Nice, 30 Years and Still Counting, Abron Arts Center, New York, New York[42]

- Art at the Center: Guerrilla Girls, 2016, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota[43]

Legacy

Ridykeulous, The Advantages of Being a Woman Lesbian Artist, 2007.

Ridykeulous, The Advantages of Being a Woman Lesbian Artist, 2007.

See also

- Feminist art movement in the United States

- Feminist art criticism

- Guerrilla Girls On Tour

- La Barbe !

References

Notes

- ↑ "Guerilla Girls Bare All".

- ↑ Brenson, Michael (April 21, 1984). "A Living Artists Show at the Modern Museum". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ↑ Stark, Lizzie. "An Interview with the Guerrilla Girls". Fringe Magazine. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ashton Cooper (2010). "Guerrilla Girls speak on social injustice, radical art". A&E. Columbia Spectator. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ↑ "Interview". Guerrilla Girls. Retrieved 2014-07-30.

- ↑ "Interview Magazine". Guerrilla Girls. Retrieved 2014-07-30.

- ↑ "Guerrilla Girls 1985-2015". MataderoMadrid. Retrieved 2016-03-05.

- ↑ "GUERRILLA GIRLS CONFERENCIA / PERFORMANCE". Vimeo. Retrieved 2016-03-05.

- ↑ "Guerrillas In Our Midst". guerrillasinourmidst.com. Retrieved 2016-03-05.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Chave, Anna C. "The Guerrilla Girls' Reckoning." Art Journal 70.2 (2011): 102-11. Web.

- ↑ Oral history interview with Guerrilla Girls Elizabeth Vigée LeBrun and Liubov Popova, January 19, 2008, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

- 1 2 3 4 Richards, Judith Olch; Hurston, Zora Neale; Martin, Agnes (2008-05-17). "Oral history interview with Guerrilla Girls Zora Neale Hurston and Agnes Martin, 2008 May 17 - Oral Histories | Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution". www.aaa.si.edu. Retrieved 2016-06-07.

- 1 2 3 Lodu, Mary (March 2016). "No No's: Guerrilla Girls at the State Theatre". INREVIEW.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Richards, Judith Olch; Bowles, Jane; Thomas, Alma (2008-05-08). "Oral history interview with Guerrilla Girls Jane Bowles and Alma Thomas, 2008 May 8 - Oral Histories | Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution". www.aaa.si.edu. Retrieved 2016-06-07.

- 1 2 Stein, Gertrude (Summer 2011). "Guerrilla Girls and Guerrilla Girls BroadBand: Inside Story". Art Journal. JSTOR 41430727.

- ↑ Cherneff, Lila, 2015-12-28, "Guerrilla Girls Stumble at MCAD," Radio Program, https://soundcloud.com/minneculture/guerrilla-girls-stumble-at-mcad, 2016-05-31, KFAI

- ↑ Jones, Hannah (2016-04-20). "The Guerrilla Girls, 'estrogen bombs' and exclusionary feminism". Twin Cities Daily Planet. Adaobi Okolue. Retrieved 2016-06-07.

- 1 2 Adams, Guy (2009-04-08). "Guerrilla girl power: Have America's feminist artists sold out?". The Independent. Independent Print Limited. Retrieved 2016-06-07.

- 1 2 "Guerrilla Girls Bare All: An Interview". Guerrilla Girls. Retrieved 2014-01-18.

- 1 2 3 Toobin, Jefffery. "Girls Behaving Badly". The New Yorker. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Judith Olch Richards (2007). "Interview with Guerrilla Girls Rosalba Carriera and Guerrilla Girl 1". Archives of American Art. Retrieved 10 Jun 2011.

- ↑ "Press releases in 2014". Amnesty International UK. Retrieved 2014-01-18.

- ↑ "Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art: Feminist Art Base: Guerrilla Girls". Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved 2014-01-18.

- ↑ Louise Bourgeois; The Spider, The Mistress & The Tangerine. Directed by Marian Cajori and Amei Wallach. 2008. New York, NY: Zeitgeist Films, 2009. DVD

- ↑ Tallman, Susan (1991). "Guerrilla Girls" (PDF). Arts Magazine. 65 (8): 21–2. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ↑ "Masking for Art". Metro. April 29, 1998.

- ↑ Archived March 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "» Guerrilla Girls vs. King Kong". Art-for-a-change.com. 2006-02-05. Retrieved 2014-01-18.

- ↑ Robinson, Walter. "Festive Venice". Artnet. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ↑ New York Times, ART: Masks Still in Place, but Firmly in the Mainstream by Phoebe Hoban, Jan 4, 2004.

- ↑ "Our Recent Books on Art History, Art Museums and Pop Culture". Guerrilla Girls. Retrieved 2015-03-07.

- ↑ "School of the Art Institute of Chicago Commencement Address" (PDF). Guerrillagirls.com. May 22, 2010. Retrieved 2014-01-18.

- ↑ Girls, Guerrilla (2003). Bitches, Bimbos, and Ballbreakers: The Guerrilla Girls' Illustrated Guide to Female Stereotypes'. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-200101-1.

- ↑ Jason, H.W. (1952). Apes and Ape Lore in the Renaissance and Middle Ages. London: The Warburg Institute, University of London. p. 291.

- ↑ "Guerrilla Girls". Collections. Art Institute of Chicago. 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- ↑ "Guerrilla Girls". Collections. Tate. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- ↑ "11 Posters Celebrating 30 Years of the Guerrilla Girls — Magazine — Walker Art Center". www.walkerart.org. Retrieved 2016-04-12.

- ↑ Ryzik, Melena (2015-08-05). "The Guerrilla Girls, After 3 Decades, Still Rattling Art World Cages". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2016-05-23.

- ↑ Holland Cotter (February 10, 1995). "Art in Review". The New York Times.

- ↑ "GUERRILLA GIRLS. Exposición retrospectiva | Bilbao International". www.bilbaointernational.com. Retrieved 2016-05-24.

- ↑ "Andy Warhol and the Guerrilla Girls | Tate". www.tate.org.uk. Retrieved 2016-05-24.

- ↑ "GUERRILLA GIRLS: NOT READY TO MAKE NICE, 30 YEARS AND STILL COUNTING | Abrons Arts Center". www.abronsartscenter.org. Retrieved 2016-05-24.

- ↑ "Art at the Center: Guerrilla Girls — Calendar — Walker Art Center". www.walkerart.org. Retrieved 2016-05-24.

Bibliography

- Boucher, Melanie. Guerrilla Girls: Disturbing the Peace. Montreal: Galerie de l'UQAM, 2010. ISBN 2-920325-32-9

- Brand, Peg. "Feminist Art Epistemologies: Understanding Feminist Art." Hypatia. 3 (2007): 166–89.

- Guerrilla Girls. Bitches, Bimbos, and Ballbreakers: The Guerrilla Girls' Illustrated Guide to Female Stereotypes. London: Penguin, 2003. ISBN 978-0-14-200101-1

- Guerrilla Girls. Confessions of the Guerrilla Girls. How a Bunch of Masked Avengers Fight Sexism and Racism in the Art World with Facts, Humor and Fake Fur. New York City: HarperCollins, 1995. ISBN 0-04-440947-8

- Guerrilla Girls. The Guerrilla Girls' Bedside Companion to the History of Western Art. London: Penguin, 1998. ISBN 978-0-14-025997-1

- Janson, HW. Apes and Ape-Lore in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. London: Warburg Institute, University of London, 1952.

- Raidiza, Kristen. "An Interview with the Guerrilla Girls, Dyke Action Machine DAM!, and the Toxic Titties." NWSA Journal. 1 (2007): 39–48. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/431723>. Accessed 27.2.2013.

- Schechter, Joel. Satiric Impersonations: From Aristophanes to the Guerrilla Girls. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0-8093-1868-1

External links

- Official website

- The Feminist Future: Guerrilla Girls a video from a talk presented at the Museum of Modern Art.

- Guerrilla Girls, Brooklyn Museum's Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art

- Guerilla Girls records, Getty Research Institute