Great Western Cattle Trail

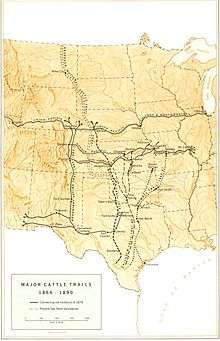

The Great Western Cattle Trail was used during the 19th century for movement of cattle and horses to markets in eastern and northern states. The trail was also known as the Western Trail, Fort Griffin Trail, Dodge City Trail, Northern Trail and Texas Trail. It replaced the Chisholm trail when it closed. While it wasn't as well known, it was greater in length, reaching rail-heads up in Kansas and Nebraska and carried longhorns and horses to stock open-range ranches in the Dakotas, Wyoming, Montana, and two provinces in Canada.

The Great Western Trail went west of and roughly parallel to the Chisholm Trail into Kansas. The cattle were taken to towns which were located on major railroads and delivered north to establish ranches. Although rail lines were built in Texas, the cattle drives continued north because of Texas rail prices, it was more profitable to trail them north.[1]

Brief History

The Great Western Cattle Trail was first traveled by Captain John T. Lytle in 1874 when he was transporting 3,500 longhorn cattle up from Southern Texas into Nebraska. In five short years, it became one of the most traveled and famous Cattle Trails in U.S. history. Despite its popularity, traffic along the trail began to decline in 1885 due to the spreading use of barbed wire fences and the legislation calling for a quarantine of Texas cattle due to the "Texas Fever" - a disease spread by a parasitic tick. The last major Cattle drive up the trail was on its way to Deadwood, South Dakota in 1893. By that time there had been an estimated six to seven million cattle and one million horses that had traversed the trail. Later, in order to commemorate the significance of the Cattle Drive era, two markers were erected in the 1930s at Doan's. Doan's was seen as the last "stepping-off point" before entering Indian Territory that sold supplies, ammo, tobacco, provisions, Stetson hats & guns, and anything else that would be required on the long trek. C.E. Doan had kept a meticulous record of the companies and Trail Bosses along with the number of cattle that crossed his path each year, allowing for numbers and history to be preserved, so a marker was fitting. In 2003 a new project was launched in order to place cement markers every six to ten miles along the trail, from the Rio Grande to Ogallala, Nebraska. Oklahoma set the first post south of the city Atlus and Texas placed their first one at the Doan's Adobe during the 121st Doan's May Day Picnic.

Markers were also placed in another major stopping point of the Great Western Cattle Trail: Seymour, Texas. One marker was erected in 1972 by the Seymour Historical Society, another four have been added since. Seymour was historically a popular campsite for cowboys since it was a major supply center. In fact, both Cowboys and Indians alike mingled in peace. In part due to the Great Western Cattle Trail's traffic, Seymour was seen as an ideal place to host a Cowboy Reunion. Jeff Scott was the retired Cowboy who broached the idea and it 'took'. In 1896 the Cowboy's Reunion was organized, and had 10,000 spectators. The following year, 1897, Native American Chief Quanah Parker attended the Reunion, where he performed war dances with 300-500 of his Braves. The tradition of the Cowboy Reunion still continues today, except that it is now called the Seymour Rodeo and Reunion, and occurs on the second weekend of each July.

Land Marks of the Great Western Cattle Trail

Due to the project launched in 2003 it is easy for people to find where the Great Western Cattle Trail was since there are now cement markers every six to ten miles along the way. It was not always so, however. Cowboys used to have to find their way using landmarks. The major ones were Mt. Tepee, Big Elk Crossing, and Soldier's Spring. Mt. Tepee is actually Mount Webster, but it looked like a giant white Tepee standing out against the rest of the Wichita Mountains, and so was a useful landmark. It wouldn't be long before they reached Big Elk Creek, and needed to cross it. Big Elk Crossing was an ideal place to get the job done. Most of the time river crossings are unfortunate because they will bog down the cattle in mud that will be difficult to push lagers and sore-footed animals through at the end.There also is the danger that an animal will break a leg. Finding a stone crossing such as Big Elk was ideal. It was placed at a horseshoe bend in the creek, which acted like a natural corral to contain and herd the animals during the crossing. After crossing, it would take maybe a day or so to reach the next landmark: Soldier's Spring. Soldier's Spring is not as easily found today. It was a huge, red, sandstone bluff that was taller than a man's head, with spring water spilling out of its face and pooling at the bottom. The reason it was called Soldier's Spring was that it reportedly had names and ranks cut into it and the surrounding rocks. It was a fantastic place to camp while along the trail. All that remains of it today is a few broken rocks and a small, spring-fed pool.

Dangers of the Great Western Cattle Trail

Despite the apparent languidness of the journey, there were always dangers. One of the major ones was stampeding. If a herd got spooked, that would mean that as many as 3,000 longhorn cattle would be in a panic-induced stampede. At that point the only thing that could safely stop them would be to corral them till they were all running in one big circle. Then the herd could let off steam safely and calm down while causing as little damage as possible. Cowboys had to be able to jump on their horses at a moments notice during the night in case of such an instance. Naturally there were precautions taken against such things. First off there was the response tactics aforementioned, but Cowboys would also sing softly to their cattle while on watch in order to cover up any sharp, unexpected noises that could cause the herd to spook, and they were extra careful when the weather turned stormy. But it wasn't only natural noises that could cause a herd to stampede.

During the time of the Great Western Cattle Trail there was also the forced relocation of Native Americans to the Cheyenne-Arapaho Reservation, effectively destroying native way of life. There are no reports of Natives being hostile to earlier Cattle Drivers, but as the Trail grew in traffic and popularity the Natives began demanding payment for the excellent grazing their territory provided. Of course, the Trail Boss never did give the usual 7 to 8 heads the Natives asked for, but usually gave 3 to 4 of the cattle that would either die on the trail, not fetch as good a price as others at market, or was one of the stragglers from a different drive. The Natives weren't exactly in a place to and didn't usually complain upon receiving beef. If they did not receive their beef, however, they would spook and stampede the herd during the night. This was not only problematic for everyone involved in the Cattle Drive, but it also meant greater potential loss than if they had peacefully paid the Native's toll, and could cause lasting damage to settlers. When hostilities got particularly bad, the Soldiers assigned to the Washita River Crossing by Edwardsville Rock was in charge of escorting Cattle Drives from the Red River's Doan Crossing to the Washita River. Fort Elliot troops took it from there. The Washita River soldiers were believed to be the ones who carved on Soldier's Spring during their patrols, though no one has ever confirmed it.

Even in cities the dangers of the trail continued. Cowboys who spent weeks on the trail were spoiling for trouble, and they found it in places such as Dodge City. With Saloons, alcohol and pent up energy, it wasn't surprising that more than a few Cowboys got involved in duels or shootings of one kind or another. The Boot Hill Cemetery at Dodge City was soon populated by Cowboys and the civilians and occasional town Marshall they put there.

See also

References

External links

- Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture - Great Western Trail

- Great Western Trail article including photos and video on TravelOK.com Official travel and tourism website for the State of Oklahoma

- Oklahoma Digital Maps: Digital Collections of Oklahoma and Indian Territory

- http://rebelcherokee.labdiva.com/cattletrail.html Contains more folklore about the Great Western Cattle Trail

- http://www.greatwesterncattletrail.com/along_gwct_a/along_gwct.html

- http://www.thegreatwesterntrail.com/

- http://www.redriverhistorian.com/greatwestern.html