Great Vowel Shift

| History and description of |

| English pronunciation |

|---|

| Historical stages |

| General development |

| Development of vowels |

| Development of consonants |

| Variable features |

| Related topics |

The Great Vowel Shift was a major change in the pronunciation of the English language that took place in England between 1350 and 1600.[1][2] Through the Great Vowel Shift, all Middle English long vowels changed their pronunciation. English spelling was becoming standardized in the 15th and 16th centuries, and the Great Vowel Shift is responsible for many of the peculiarities of English spelling.[3]

History of analysis

The Great Vowel Shift was first studied by Otto Jespersen (1860–1943), a Danish linguist and Anglicist, who coined the term.[4]

Overall changes

The main difference between the pronunciation of Middle English in the year 1400 and Modern English (Received Pronunciation) is in the value of the long vowels. Long vowels in Middle English had "continental" values, much like those in Italian and Standard German, but in standard Modern English, they have entirely different pronunciations. The change in pronunciation is known as the Great Vowel Shift.[5]

| Word | Vowel pronunciation | |

|---|---|---|

| Late Middle English before the GVS | Modern English after the GVS | |

| bite | /iː/ | /aɪ/ |

| meet | /eː/ | /iː/ |

| meat | /ɛː/ | |

| mate | /aː/ | /eɪ/ |

| out | /uː/ | /aʊ/ |

| boot | /oː/ | /uː/ |

| boat | /ɔː/ | RP /əʊ/, GA /oʊ/ |

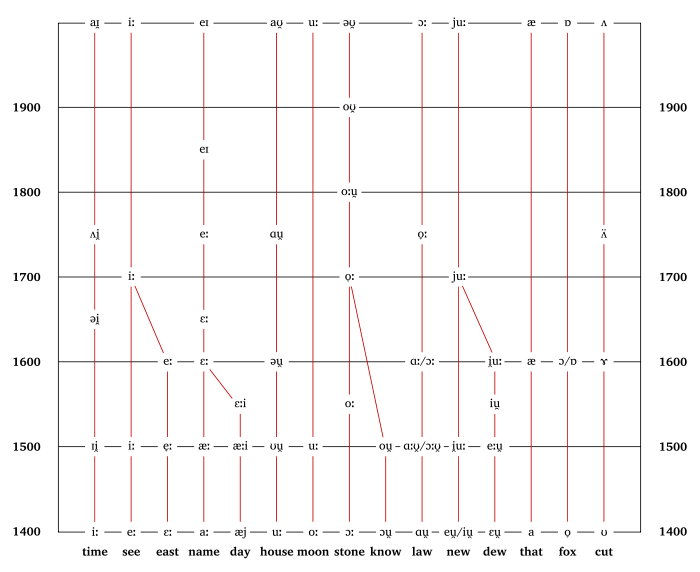

This timeline shows the main vowel changes that occurred between late Middle English in the year 1400 and Modern English in the mid-20th century by using representative words. The Great Vowel Shift occurred in the lower half of the table, between 1400 and 1600. The changes that happened after 1600 are not usually considered part of the Great Vowel Shift proper. Pronunciation is given in the International Phonetic Alphabet:[6]

Details

Middle English vowel system

Before the Great Vowel Shift, Middle English in Southern England had seven long vowels, /iː eː ɛː aː ɔː oː uː/. The vowels occurred in the words bite, meet, meat, mate, boat, boot and out.

| front | back | |

|---|---|---|

| close | /iː/: bite | /uː/: out |

| close-mid | /eː/: meet | /oː/: boot |

| open-mid | /ɛː/: meat | /ɔː/: boat |

| open | /aː/: mate | — |

The words had very different pronunciations in Middle English from their pronunciations in Modern English. Long i in bite was pronounced as /iː/ so Middle English bite sounded like Modern English beet /biːt/; long e in meet was pronounced as /eː/ so Middle English meet sounded similar to Modern English mate /meɪt/; long a in mate was pronounced as /aː/, with a vowel like Modern English ah in father /fɑːðər/; and long o in boot was pronounced as /oː/, similar to modern oa in American English boat /oʊ/. In addition, Middle English had a long /ɛː/ in beat, like modern short e in bed but pronounced longer, and a long /ɔː/ in boat, like the vowel of law /lɔː/ in British English.

Changes

After around 1300, the long vowels of Middle English began changing in pronunciation. The two close vowels, /iː uː/, became diphthongs (vowel breaking), and the other five, /eː ɛː aː ɔː oː/, underwent an increase in tongue height (raising).

The changes are known as the Great Vowel Shift. They occurred over several centuries and can be divided into two phases. The first phase affected the close vowels /iː uː/ and the close-mid vowels /eː oː/: /eː oː/ were raised to /iː uː/, and /iː uː/ became the diphthongs /ei ou/ or /əi əu/.[7] The second phase affected the open vowel /aː/ and the open-mid vowels /ɛː ɔː/: /aː ɛː ɔː/ were raised, in most cases changing to /eː iː oː/.[8]

The Great Vowel Shift changed vowels without merger so Middle English before the vowel shift had the same number of vowel phonemes as Early Modern English after the vowel shift. After the Great Vowel Shift, some vowel phonemes began merging. Immediately after the Great Vowel Shift, the vowels of meet and meat were different, but they are merged in Modern English, and both words are pronounced as /miːt/. However, during the 16th and the 17th centuries, there were many different mergers, and some mergers can be seen in individual Modern English words like great, which is pronounced with the vowel /eɪ/ as in mate rather than the vowel /iː/ as in meat.[9]

This is a simplified picture of the changes that happened between late Middle English and today's English. Pronunciations in 1400, 1500, 1600.and 2000 are shown.[5] To hear recordings of the sounds, click the phonetic symbols.

| Word | Vowel pronunciation | Soundfile | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| late ME | EModE | ModE | |||

| 1400 | 1500 | 1600 | 2000 | ||

| bite | | /ei/ | /ɛi/ | | |

| meet | | | /iː/ | /iː/ | |

| meat | | /ɛː/ | | | |

| mate | | /aː/ | | | |

| out | | /ou/ | /ɔu/ | | |

| boot | | | /uː/ | /uː/ | |

| boat | | /ɔː/ | | | |

Before labial consonants, /uː/ did not shift, and [uː] remains as in soup and room (its Middle English spelling was roum).

First phase

The first phase of the Great Vowel Shift affected the Middle English close-mid vowels /eː oː/, as in beet and boot, and the close vowels /iː uː/, as in bite and out. The close-mid vowels /eː oː/ became close /iː uː/, and the close vowels /iː uː/ became diphthongs. The first phase was complete in 1500, meaning that by that time, words like beet and boot had lost their Middle English pronunciation, and were pronounced with the same vowels as in Modern English. The words bite and out were pronounced with diphthongs, but not the same diphthongs as in Modern English.[7]

| Word | Vowel pronunciation | |

|---|---|---|

| 1400 | 1550 | |

| bite | /iː/ | /ɛi/ |

| meet | /eː/ | /iː/ |

| out | /uː/ | /ɔu/ |

| boot | /oː/ | /uː/ |

Scholars agree that the Middle English close vowels /iː uː/ became diphthongs around the year 1500, but disagree about what diphthongs they changed to. According to Lass, the words bite and out after diphthongization were pronounced as /beit/ and /out/, similar to American English bait /beɪt/ and oat /oʊt/. Later, the diphthongs /ei ou/ shifted to /ɛi ɔu/, then /əi əu/, and finally to Modern English /aɪ aʊ/.[7] This sequence of events is supported by the testimony of orthoepists before Hodges in 1644.

However, many scholars such as Dobson (1968), Kökeritz (1953), and Cercignani (1981) argue for theoretical reasons that, contrary to what 16th-century witnesses report, the vowels /iː uː/ were actually immediately centralized and lowered to [əi əu].

Logically, the close vowels /iː uː/ had to diphthongise before the close-mid vowels /eː oː/ raised or else /eː/ would have merged with /iː/, and /oː/ with /uː/, and the pairs beet and bite as well as boot and out would have the same vowels. However, evidence from northern English and Scots (see below) shows that raising of the close-mid vowels /eː oː/ caused the close vowels /iː uː/ to shift, not the other way around. As the Middle English vowels /eː oː/ were raised towards /iː uː/, they forced the original Middle English /iː uː/ out of place and caused them to become diphthongs /ei ou/. That vowel shift is called a push chain.[10]

Second phase

The second phase of the Great Vowel Shift affected the Middle English open vowel /aː/, as in mate, and the Middle English open-mid vowels /ɛː ɔː/, as in meat and boat. Around 1550, Middle English /aː/ was raised to /æː/. Then, after 1600, the new /æː/ was raised to /ɛː/, with the Middle English open-mid vowels /ɛː ɔː/ raised to close-mid /eː oː/. [11]

| Word | Vowel pronunciation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1400 | 1550 | 1640 | |

| meat | /ɛː/ | /ɛː/ | /eː/ |

| mate | /aː/ | /aː/, /æː/ | /ɛː/ |

| boat | /ɔː/ | /ɔː/ | /oː/ |

Later mergers

During the first and the second phases of the Great Vowel Shift, long vowels were shifted without merging with other vowels, but after the second phase, several vowels merged. The later changes also involved the Middle English diphthong /ai/, as in day, which had monophthongised to /ɛː/, and merged with Middle English /aː/ as in mate or /ɛː/ as in meat.[9]

During the 16th and 17th centuries, several different pronunciation variants existed among different parts of the population for words like meet, meat, mate, and day. In each pronunciation variant, different pairs or trios of words were merged in pronunciation. Four different pronunciation variants are shown in the table below. The fourth pronunciation variant gave rise to Modern English pronunciation. In Modern English, meet and meat are merged in pronunciation and both have the vowel /iː/, and mate and day are merged with the diphthong /eɪ/, which developed from the 16th-century long vowel /eː/.[9]

| Word | 16th century pronunciation variants | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| meet | /iː/ | /iː/ | /iː/ | /iː/ |

| meat | /ɛː/ | /eː/ | /eː/ | |

| day | /ɛː/ | /eː/ | ||

| mate | /æː/ | |||

Modern English typically has the meet–meat merger: both meet and meat are pronounced with the vowel /iː/. Words like great and steak, however, have merged with mate and are pronounced with the vowel /eɪ/, which developed from the /eː/ shown in the table above.

Northern English and Scots

The Great Vowel Shift affected other dialects as well as the standard English of southern England but in different ways. In Northern England, the long back vowels remained unaffected because the long mid back vowel had undergone an earlier shift.[12] The Scots language, in Scotland, had a different vowel system before the Great Vowel Shift. The long vowels [iː], [eː] and [aː] shifted to [ei], [iː] and [eː] by the Middle Scots period, [oː] had shifted to [øː] in Early Scots and [uː] remained unaffected.[13]

Northern English and Scots went through the Great Vowel Shift like the English in Southern England, but the developments of Middle English /iː eː/ and /oː uː/ were different from Southern English. In particular, Northern English has shifting of /iː eː oː/, but not of /uː/. The words bite, feet, boot have shifted vowels, but house does not:

| Word | Vowel | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Middle English | Northern | Southern | |

| bite | /iː/ | /ɛi/ | /ai/ |

| feet | /eː/ | /iː/ | /iː/ |

| house | /uː/ | /uː/ | /au/ |

| boot | /oː/ | /iː/ | /uː/ |

The lack of diphthongisation of /uː/ is explained by the Northern English development of the Middle English vowel /oː/, as in boot. Before the Great Vowel Shift, /oː/ was fronted and changed to front mid /øː/. Thus, there was no /oː/ in Northern English, only /uː/, at the time of the Great Vowel Shift, but there were three front vowels, /iː eː øː/:[10]

|

|

The Great Vowel Shift acted on these Northern and Southern Middle English vowel systems. In both Northern and Southern English, close-mid vowels were raised: Northern /eː øː/ were raised to /iː, yː/ (and later /yː/ was unrounded to /iː/), and Southern /eː oː/ were raised to /iː uː/. However, in Southern English, both the front and back close vowels /iː uː/ were diphthongised, but in Northern English, /iː/ diphthongised but /uː/ did not.

If this Northern–Southern difference is related to the vowel systems shown above, the lack of the back mid vowel /oː/ in Northern English explains why /uː/ did not shift. In Southern English, shifting of /oː/ to /uː/ must have caused diphthongisation of original /uː/, but because Northern English had no back close-mid vowel /oː/ to shift, the back close vowel /uː/ did not diphthongise.

Exceptions

Not all words underwent certain phases of the Great Vowel Shift; in particular, ea did not take the step to [iː] in several words such as great, break, steak, swear and bear. The vowels mentioned in words like break or steak underwent shortening, possibly by the plosives following the vowels, and then diphthongization. The presence of [r] in swear and bear caused the vowel quality to be retained but not in the cases of hear and near.

Other examples are father, which failed to become [ɛː], and broad, which failed to become [oʊ]. The word room, which was spelled as roum in Middle English, retains its Middle English pronunciation. It is an exception to the shifting of [uː] to [aʊ] because it is followed by m, a labial consonant.

Shortening of long vowels at various stages produced further complications: ea is again a good example by shortening commonly before coronal consonants such as d and th, thus: dead, head, threat, wealth etc. (That is known as the bred–bread merger.) The oo was shortened from [uː] to [ʊ], in many cases before k, d and less commonly t: book, foot, good, etc. Some words subsequently changed from [ʊ] to [ʌ]: blood, flood. Similar but older shortening occurred for some instances of ou: could.

Some loanwords, such as soufflé and Umlaut, have retained a spelling from their origin language that may seem similar to the previous examples; but, since they were not a part of English at the time of the Great Vowel Shift, they are not actually exceptions to the shift.

Spelling

The printing press was introduced to England in the 1470s by William Caxton and later Richard Pynson. The adoption and use of the printing press accelerated the process of standardization of English spelling, which continued into the 16th century. The standard spellings were those of Middle English pronunciation, and spelling conventions continued from Old English. However, the Middle English spellings were retained into Modern English while the Great Vowel Shift was taking place, which caused some of the peculiarities of Modern English spelling in relation to vowels.

See also

- Canaanite Shift

- Chain shift

- Vowel shift

- Consonant mutation

- History of the English language

- International Phonetic Alphabet

- Phonological history of English vowels

- "The Chaos"

References

Notes

- ↑ Stockwell, Robert (2002). "How much shifting actually occurred in the historical English vowel shift?" (PDF). In Minkova, Donka; Stockwell, Robert. Studies in the History of the English Language: A Millennial Perspective (PDF). Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-017368-9.

- ↑ Wyld, H. C. (1957) [1914], A Short History of English

- ↑ Denham, Kristin; Lobeck, Anne (2009), Linguistics for Everyone: An Introduction, Cengage Learning, p. 89

- ↑ Labov, William (1994). Principles of Linguistic Change. Blackwell Publishing. p. 145. ISBN 0-631-17914-3.

- 1 2 Lass 2000, p. 72.

- ↑ Wheeler, L Kip. "Middle English consonant sounds" (PDF).

- 1 2 3 Lass 2000, pp. 80–83.

- ↑ Lass 2000, pp. 83–85.

- 1 2 3 Görlach 1991, pp. 68–69.

- 1 2 Lass 2000, pp. 74–77.

- ↑ Lass 2000, pp. 83-85.

- ↑ Wales, K (2006). Northern English: a cultural and social history. Cambridge: Cambridge University. p. 48.

- ↑ Macafee, Caroline; Aitken, A. J., A History of Scots to 1700, DOST, 12, pp. lvi–lix

Bibliography

- Baugh, Alfred C.; Cable, Thomas (1993). A History of the English Language (4 ed.). Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

- Cable, Thomas (1983). A Companion to Baugh & Cable's History of the English Language. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

- Cercignani, Fausto (1981). Shakespeare's Works and Elizabethan Pronunciation. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Dillon, George L., "American English vowels", Studying Phonetics on the Net

- Dobson, E. J. (1968). English Pronunciation 1500-1700 (2 vols) (2 ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. (See vol. 2, 594-713 for discussion of long stressed vowels)

- Freeborn, Dennis (1992). From Old English to Standard English: A Course Book in Language Variation Across Time. Ottawa, Canada: University of Ottawa Press.

- Görlach, Manfred (1991). Introduction to Early Modern English. Cambridge University Press.

- Kökeritz, Helge (1953). Shakespeare's Pronunciation. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Lass, Roger (2000). "Chapter 3: Phonology and Morphology". In Lass, Roger. The Cambridge History of the English Language, Volume III: 1476–1776. Cambridge University Press. pp. 56–186.

- Millward, Celia (1996). A Biography of the English Language (2 ed.). Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace.

- Pyles, Thomas; Algeo, John (1993). The Origins and Development of the English Language (4 ed.). Orlando, FL: Harcourt Brace & Co.

- Rogers, William 'Bill', A Simplified History of the Phonemes of English, Furman

External links

- Great Vowel Shift Video lecture

- Menzer, M., "What is the Great Vowel Shift?", Great Vowel Shift, Furman University

- "The Great Vowel Shift", Geoffrey Chaucer, Harvard University