Grand Manan Island

| Grand Manan | ||

|---|---|---|

| Island | ||

|

Beach along Grand Manan's North Head | ||

| ||

| Nickname(s): "Queen of the Fundy Isles" | ||

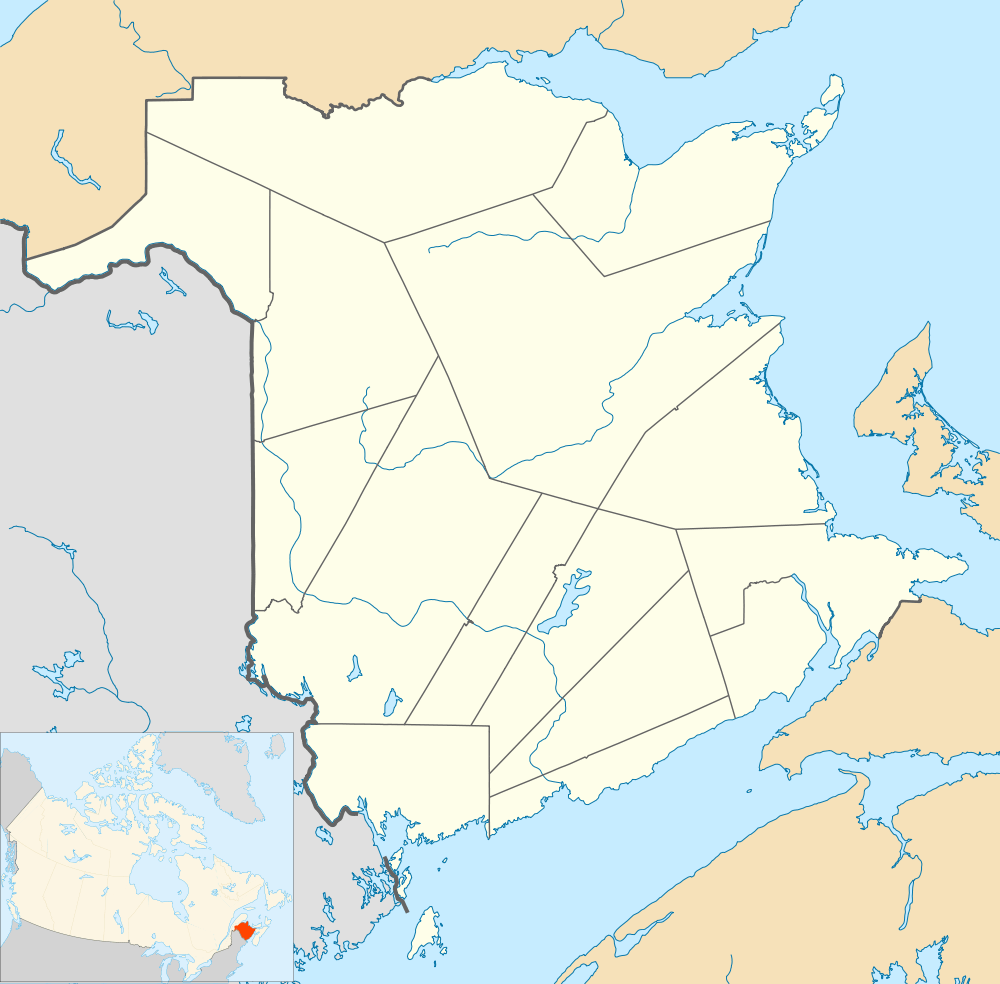

Grand Manan Location in Bay of Fundy, New Brunswick, Canada | ||

| Coordinates: 44°41′N 66°49′W / 44.69°N 66.82°WCoordinates: 44°41′N 66°49′W / 44.69°N 66.82°W | ||

| Country | Canada | |

| Province | New Brunswick | |

| County | Charlotte | |

| Parish | Grand Manan Parish | |

| Settled | 1784 | |

| Incorporated | 1854 | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 655.89 km2 (253 sq mi) | |

| • Land | 142 km2 (55 sq mi) | |

| • Water | 513.89 km2 (198.4 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 78 m (255 ft) | |

| Population (2006) | ||

| • Total | 2,460 | |

| • Density | 17.3/km2 (45/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | Atlantic (UTC-4) | |

| • Summer (DST) | Atlantic (UTC-3) | |

| Postal code | E5G0A1 | |

| Area code(s) | 506 | |

| LORAN | 4443.00N | |

| LORAN | 06648.00W | |

| WMO Id: | 71030 | |

| LFA (Lobster Fishing Area) | Area 38 | |

| Demonym | "Grand Mananer" | |

| Website | www.grandmanannb.com | |

Grand Manan Island (also simply Grand Manan) is a Canadian island, and the largest of the Fundy Islands in the Bay of Fundy. It is also the primary island in the Grand Manan Archipelago, sitting at the boundary between the Bay of Fundy and the Gulf of Maine on the Atlantic coast. Grand Manan is jurisdictionally part of Charlotte County in the province of New Brunswick. As of 2006, the island had a population of 2,460.

Geography

Grand Manan is specifically located at coordinates 44.42 N and 66.48 W or right beside White Head Island. The island rests in the midwestern end of the Bay of Fundy, a body of water between the provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, and home to some of the most extreme tides in the world. Located 32 kilometres south of Blacks Harbour, the point on mainland closest to the island is in Washington County, Maine, near the town of Lubec—the easternmost point of the continental United States, where the distance to the island measures 15 km (9.3 mi) across the Grand Manan Channel. Grand Manan is 34 km (21 mi) long and has a maximum width of 18 km (11 mi) with an area of 137 square kilometres (53 sq mi).

The vast majority of Grand Manan residents live on the eastern side of the island. Due to limited access, 91-metre (300 ft) cliffs, and high winds, the western side of the island is not residentially developed, although it does feature wind-power ventures and camps at Dark Harbour, a small dulsing community and get-away destination for islanders. Grand Manan has a network of trails for all-terrain vehicles, hiking, mountain biking, nature walks, and presents a challenging landscape for jogging. There are a number of fresh-water ponds, lakes and beaches that are prime locations for sun-bathing, beach combing, and picnics. Other interesting finds on Grand Manan are magnetic sand, and "The Hole-In-The Wall" located in Whale Cove in the village of North Head. Anchorage Provincial Park can be found on the island's southeastern coast between the communities of Grand Harbour and Seal Cove.

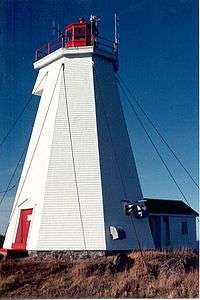

White Head Island, Gull Rock, Machias Seal Island, and North Rock are part of the larger Grand Manan archipelago; the latter two are about 15 kilometres southwest of Grand Manan Island. Both Machias Seal Island and North Rock are claimed by both Canada and the United States. For administrative purposes, they form the most southerly part of New Brunswick. Machias Seal Island also houses the province's last remaining staffed lighthouse. The light has been in continuous operation since 1832; the post of lighthouse-keeper was withdrawn for cost-saving reasons in the 1990s, but soon reinstated to provide a human demonstration of national sovereignty. Research is conducted on the island by the Atlantic Cooperative Wildlife Ecology Research Network at the University of New Brunswick in Fredericton.

Geology

Grand Manan has a "split personality" regarding its geology. The western ⅔ of the island shows thick lava flows (basalt) of Late Triassic age, which appear little changed from when they cooled around 201 million years (m.y.) ago. They are part of a massive "flood basalt" that underlies most of the Bay of Fundy, although the Grand Manan Basalt was later separated into its own rift basin by block faulting [ref. McHone, 2011]. The Fundy basalts are themselves only a small portion of the enormous Central Atlantic Magmatic Province or CAMP, which was formed in a volcanic event preceding the breakup of the supercontinent Pangaea in Early Jurassic time. These lava flows also crop out along the western shores of Nova Scotia, where they are known as the North Mountain Basalt. Both there and on our island, many interesting minerals have filled the cracks and bubbles left by gases boiling out of the cooling lavas. They include zeolite minerals such as chabazite, mesolite, stilbite, and heulandite, plus attractive quartz-related amethyst, agate, jasper, and many others. Good collecting areas include Seven Days Work, Indian Beach, and Bradford Cove. A few meters of siltstone are exposed under the basalt along the western shoreline, which by analogy with the Blomidon Formation in Nova Scotia must include the Triassic-Jurassic boundary [ref. McHone, 2011].

Inhabitants of the island live mainly around harbors along the eastern shoreline, which were created by the erosion of complex fault and fold structures in ancient metamorphosed sedimentary and volcanic rock formations. A major north-south fault is exposed at Red Point, and it divides these older eastern rocks from the much younger basalts that form the western ⅔ of the island. The metamorphic formations are organized into groups called Castalia, Ingalls Head, and Grand Manan, and there are also metamorphosed plutonic masses such as Stanley Brook Granite, Rockweed Pond Gabbro, and Kent Island Granite [ref. Fyffe and others, 2011]. These rocks have recently been dated between 539 and 618 million years old [ref. Black and others, 2007] and are now considered to correlate with the New River and Mascarene terranes of southern New Brunswick, Canada. Although originally they were igneous and sedimentary rocks such as basalt, sandstone, and shale, the eastern formations have been metamorphosed into greenstone, phyllite, argillite, schist, quartzite, and other foliated types. In addition, many folds and faults have bent and broken the formations in rather tortured-looking outcrops. One such fault can be seen at the north end of Pettes Cove, where it separates metabasalt of Swallowtail Head from schist of North Head.

Climate

Grand Manan experiences a Humid continental climate (Dfb). The climate in spring, summer and fall is very comfortable but winter has an inconsistent weather pattern with snow, rain, freezing rain and mild weather. Since 2000, the average annual precipitation has been 859.8 mm with August being the driest month (35 mm) and October (112 mm) providing the most precipitation.

The highest temperature ever recorded on Grand Manan was 33.3 °C (92 °F) on 26 July 1963.[1] The coldest temperature ever recorded was −30.6 °C (−23 °F) on 10 January 1890.[2]

| Climate data for Grand Manan (Seal Cove), 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1883–present[lower-alpha 1] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16.1 (61) |

15.0 (59) |

25.6 (78.1) |

23.9 (75) |

30.5 (86.9) |

32.8 (91) |

33.3 (91.9) |

32.5 (90.5) |

31.9 (89.4) |

27.0 (80.6) |

18.3 (64.9) |

18.7 (65.7) |

33.3 (91.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −0.3 (31.5) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

3.0 (37.4) |

8.1 (46.6) |

14.0 (57.2) |

18.0 (64.4) |

20.7 (69.3) |

21.0 (69.8) |

17.8 (64) |

12.6 (54.7) |

7.2 (45) |

2.0 (35.6) |

10.3 (50.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −4.6 (23.7) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

4.1 (39.4) |

9.1 (48.4) |

13.1 (55.6) |

15.7 (60.3) |

16.1 (61) |

12.8 (55) |

8.3 (46.9) |

3.6 (38.5) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

5.9 (42.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −8.9 (16) |

−8.6 (16.5) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

0.0 (32) |

4.3 (39.7) |

8.0 (46.4) |

10.7 (51.3) |

11.1 (52) |

7.7 (45.9) |

4.0 (39.2) |

0.0 (32) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

1.5 (34.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −30.6 (−23.1) |

−26.3 (−15.3) |

−23.9 (−11) |

−13.6 (7.5) |

−3.9 (25) |

−5.0 (23) |

3.0 (37.4) |

0.7 (33.3) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

−7.6 (18.3) |

−16.7 (1.9) |

−28.0 (−18.4) |

−30.6 (−23.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 128.9 (5.075) |

87.5 (3.445) |

114.5 (4.508) |

98.6 (3.882) |

101.1 (3.98) |

81.9 (3.224) |

74.9 (2.949) |

73.3 (2.886) |

112.7 (4.437) |

123.2 (4.85) |

134.0 (5.276) |

121.6 (4.787) |

1,252.2 (49.299) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 79.5 (3.13) |

52.7 (2.075) |

78.1 (3.075) |

83.1 (3.272) |

100.9 (3.972) |

81.9 (3.224) |

74.9 (2.949) |

73.3 (2.886) |

112.7 (4.437) |

123.2 (4.85) |

127.8 (5.031) |

95.0 (3.74) |

1,082.9 (42.634) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 49.5 (19.49) |

34.8 (13.7) |

36.5 (14.37) |

15.5 (6.1) |

0.2 (0.08) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

6.1 (2.4) |

26.6 (10.47) |

169.3 (66.65) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 13.1 | 9.9 | 13.1 | 14.6 | 15.8 | 15.9 | 14.6 | 14.9 | 15.6 | 15.7 | 16.4 | 13.9 | 173.6 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 7.1 | 5.3 | 9.6 | 13.3 | 15.7 | 15.9 | 14.6 | 14.9 | 15.6 | 15.7 | 15.8 | 10.3 | 153.9 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 6.5 | 5.4 | 5.0 | 2.2 | 0.08 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.3 | 4.5 | 25.0 |

| Source: Environment Canada[3][4][5] | |||||||||||||

History

Exploration

"Manan" is a corruption of "mun-an-ook" or "man-an-ook", meaning "island place" or "the island", from the Maliseet-Passamaquoddy-Penobscot Indians who, according to oral history, used Grand Manan and its surrounding islands as a safe place for the elderly Passamaquoddy during winter months and as a sacred burial place ("ook"-means "people of"). Although there is no actual evidence, the Norse are believed by some to be the first Europeans to visit Grand Manan while exploring the Bay of Fundy and Gulf of Maine around 1000 A.D. By the late 15th century, famed explorers Sebastian Cabot and Gaspar Corte-Real, while separately exploring the New World, likely saw what is now known as Grand Manan and the Bay of Fundy. During the early 16th century, Breton fishermen are said to have fished the teeming waters around the island and sheltered among its old-growth oak forests.

Portuguese explorer João Álvares Fagundes charted the area around Grand Manan in about 1520, yet the island does not appear clearly on a map until 1558. Reports of a rich land led the Portuguese to decide the area was important enough to include in a comprehensive map of the New World. Famed cartographer Diogo Homem produced this map, noting what would later be called Grand Manan and surrounding islands. The name "Fundy" is thought to date to this time when the Portuguese and Breton fishermen referred to the bay as "Rio Fundo" or "deep river".

It is likely this map ignited a fascination in the region in French merchant-explorer Stephen Bellinger (Étienne Bellenger). Wishing to cash in on the bounty of this newly discovered paradise, Bellinger set out aboard the Chardon in January 1583, reaching Cape Breton about 7 February. He sailed down one side of what is now Nova Scotia and entered "the great bay of that island", namely, the Bay of Fundy (Baie Française). As he noted that "the entrance is so narrow that a culverin shot can reach from one side to the other", it would appear that he passed (if the coast has not changed in the meantime) between Long Island and Digby Neck into the bay.

He gave names to many places as he continued to explore the bay, and some of those names which he gave to the northern shore survived his voyage. It would appear that he emerged from the Bay of Fundy between Grand Menane (Grand Manan) Island and what is now Maine.

The Chardon or her pinnace put Bellinger on land ten to a dozen times. He made a close examination of the resources of the mainland, its timber, its possibilities for making salt, and its presumed mineral wealth, bringing home an ore believed to contain lead and silver. He also made frequent contacts with the Passamaquoddy-Penobscot Indians. He noted that "natives" who lived from 60 to 80 leagues westward from Cape Breton were cunning, cruel, and treacherous: he lost two of his men and his pinnace to them as he made his way back along the Nova Scotia shore. However, he found the Passamaquoddy Indians further west and along the area around what is now Maine and Grand Manan, gentle and tractable. He had a quantity of small merchandise for trade and acquired from the Indians in return for it dressed "buff" (probably elk), deer, and seal skins, together with marten, beaver, otter, and lynx pelts, samples of castor, porcupine quills, dye stuffs, and some dried deer-flesh.

In 1606, French Explorer Samuel de Champlain, in a voyage on behalf of Henry IV, sailed the Bay of Fundy and sheltered on White Head—an outer island of Grand Manan—during a March storm of that year. Seven years later, Champlain had produced a detailed map of what he saw, calling the "big" island "Manthane", which he later corrected to Menane or Menasne. "Grand" was formally added to its name later.

In 1693, the island of "Grand Manan" was granted to Paul D'Ailleboust, Sieur de Périgny as part of Champlain's "New France". D'Ailleboust did not take possession of it, and it reverted to the French Crown, in whose possession it remained until 1713, when it was traded to the British in the Treaty of Utrecht.

Colonial era

Despite earlier exploration and trade activity, the first permanent settlement of Grand Manan was not established until 1784, when Moses Gerrish gathered a group of settlers on an area of Grand Manan he called Ross Island, in honour of settler Thomas Ross.

By this time, the United States had formed. Because of the Treaty of Paris (1783), the U.S. considered Grand Manan to be its possession due to the island's proximity to Maine. For many years, the United States and Britain would squabble over the ownership of Grand Manan. Britain obtained better title to Grand Manan in Jay's Treaty of 1794, while surrendering its sovereignty claims over Eastport on Moose, Frederick and Dudley islands in nearby Cobscook Bay.

However, ownership by either country was not fully agreed-upon in the local trading communities of the era.

Nineteenth century to the present

During the period of 1812-1814, the Bay of Fundy was infested with privateers. Settlers of the island saw much hardship during these years, as privateers from both sides occasionally raided villages along Grand Manan's east shore and plundered their belongings. Much of eastern coastal Maine near Grand Manan was occupied by British military forces during and after the war, with Eastport not returned to US control until 1818.

The actual boundary and ownership of local islands in Passamaquoddy Bay was not settled until 1817, when the United States gave up its claim to Grand Manan and the surrounding islands.

By 1832, the island had become a destination for those seeking prosperity and privacy. Schools were established by the Anglican Church. While neighbouring islands along the American coast to Boston relied on whaling, Grand Manan established a reputation for fishing and shipbuilding. The early 19th century saw the harvesting of hackmatack, birch and oak and a burgeoning shipbuilding community. Population on the island grew to include many fine carpenters, and Grand Manan became known for its accomplished maritime craftsmen.

This period was also marked by a number of shipwrecks off the island's rocky, cliff-lined coast. One of the most famous of these wrecks, that of the Lord Ashburton, took place during the winter of 1857. Having crossed the Atlantic from France, and under 60 miles from its destination port of Saint John, the Lord Ashburton was driven into the cliffs at the northern end of the island by hurricane-force winds. The captain, three mates and the crew of 28 were swept overboard. Only eight of the men survived, and they were provided for by local villagers. The bodies of those who perished were recovered from the base of the cliff the following day and buried in the cemetery in the village of North Head, where a monument was later erected in their memory. Another wreck was the Nova Scotian barque Walton, which was bound for Saint John, New Brunswick, from Wales when she wrecked on the White Ledge off Grand Manan on September 14, 1878.[6]

By 1851, the island population numbered almost 1,200 permanent inhabitants, most working in what had become an exceedingly prosperous industry: fishing.

By 1884, Grand Manan became the largest supplier of smoked herring in the world. By 1920, it produced a staggering one million boxes—or twenty thousand tons—of smoked herring, all caught in its local waters.

Despite world acclaim, islanders fiercely guarded their "Fundy Oasis", choosing instead to create and preserve a quiet, private life in an idyllic setting. However, as early as 1875, word spread among wealthy travellers and educated wanderers looking to escape the oppression and industrialization of the Eastern Seaboard; word of a sort of paradise; a fortress of civility and privacy untainted by the outside world. By the late Victorian era, Grand Manan had been discovered by a new breed of explorers—the "tourists"—who began visiting the island in steady numbers, weaving themselves into the fabric of its close-knit, isolated society. Pulitzer Prize–winning author Willa Cather loved the island's unspoiled solitude, while painters such as Alfred Thompson Bricher and John James Audubon came to Grand Manan and its outlying islands to capture what they believed to be its "unique majesty", documenting its varied geography and indigenous fauna.

In 1995, the island's settlements—North Head, Castalia, Woodwards Cove, Grand Harbour, Ingalls Head and Seal Cove—were amalgamated into a single municipal government, known as the Village of Grand Manan.

In 2006, Grand Manan residents caused some controversy when they burned out a supposed drug dealer's house.[7]

Notable people

Grand Manan has an impressive list of residents and visitors. In keeping with the intense privacy pursued by some of those who visit and live there, many of its most notable residents and summer visitors wish to remain in relaxed anonymity. A partial list of those associated with Grand Manan who are known for their contributions to art, science, politics and scholarship include:

Historical personages

- Samuel de Champlain (c. 1575 – 25 of December 1635), explorer and cartographer, sailed the Bay of Fundy and sheltered on White Head, an outer island of Grand Manan, during a March storm

- Dr. John Faxon, Brown graduate, War of 1812 veteran; first physician on the island

- William "Captain" Kidd (1645–1701), Scottish sailor; profiteer; pirate. An early Manhattan Island resident, a treasure once buried on Gardiners Island, New York. Legend holds his burying money on the west side of Grand Manan island. For nearly 200 years, the spot he reportedly visited has been called "Money Cove".

- John Sterling Rockefeller, grandson of Standard Oil co-founder William Rockefeller. Moved by the enthusiasm of Grand Manan native and gifted taxidermist Allan Moses, Rockefeller purchased Kent Island, off-island of Grand Manan, to preserve Bay of Fundy eider ducks and other native fowl. Mr. Rockefeller's generous gift flourishes today; the island was given to Bowdoin College for continuing research.

Artists

- John James Audubon (April 26, 1785 – January 27, 1851), Grand Manan's first official bird watcher. Audubon immortalized the ornithology of the island in 1831. With 240 species of birds, including bald eagles, buffleheads, puffins and osprey, Grand Manan provided Audubon with endless inspiration for his naturalist paintings, many of which he sketched while residing on the island.

- William James Aylward, painter, illustrator, member of the Brandywine School, illustrator for Harper's Weekly

- Alfred Thompson Bricher (1837–1908), American marine painter associated with White Mountain art and the Hudson River School; spent 17 years coming to Grand Manan[8] where many of his masterpieces were created, including Lifting Fog, Grand Manan

- Harrison Bird Brown (1831–1915), White Mountain painter who frequented the island

- John George Brown (1831–1913), American painter, born in Durham, England. Edinburg Academy; painted Reading on the Rocks, Grand Manan about 1877

- Milton J. Burns, whose 1853 Swallowtail Lighthouse is on display at the U.S. Coast Guard Museum

- Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900), American landscape painter. His use of color is unparalleled; his work Heart of the Andes sold for $10,000 in 1859. His contribution to the island's artistic stature, Grand Manan, is one of his important works.

- Peter Cunningham, American photographer

- Mauritz de Haas (1832–1895), Dutch-American marine painter; realist. Exhibited Paris Exposition. One of the founders of the American Society of Painters in Water Colors. His Fishermen off Grand Manan is considered one of his best works.

- William Frederick de Haas (1830–1880), Dutch-American marine painter; brother of Mauritz de Haas; also favoured the island's inspiration

- M. J. Edwards, born in Kingston, Ontario; photographer; visual artist; educator; Grand Manan Museum curator/director

- Robert Swain Gifford (1840–1905), American landscape painter influenced by the Barbizon school; his work from the North Head, Pettes Cove, is a masterful example of marine painting

- Erica Deichmann Gregg (1913–2007), potter, artist, educator and philanthropist

- Wesley Griffin, painter; several of his works hang in public places on the island, including Young Captain in the library

- Winslow Homer (1836–1910), American illustrator and painter, self-taught; created Morning at Grand Manan

- Edward Moran (1829–1901), Royal Academy of London, Devil's Crag; Island of Grand Manan

- Lori P. Morse, born on Grand Manan; artist, photographer, musician, artistic and graphics curator; family of the Samuel F.B. Morse/Morse Code fame

- Allan Moses, taxidermist from Grand Manan, world traveller, naturalist, philanthropist; instrumental in the purchase of Kent Island by John Sterling Rockefeller for preservation

- Lucius Richard O'Brien (1832–1899), whose Grand Manan interpretation is called The Grand Cross

Writers

- Gene Brewer, author (K-Pax)

- Willa Cather (1873–1947), Pulitzer Prize–winning author, member of the intellectual salon "Cottage Girls" of Grand Manan

- Wayne Clifford, born in Toronto; poet and writer (Man in a Window)

- Alice Coney, member of the "Cottage Girls" salon of Grand Manan

- P. Wendy Dathan, naturalist and author of Bauxite, Sugar and Mud: Memories of Living in Colonial Guyana, 1928-1944 (2006); Swallowtail Calling: A Naturalist Dreams of Grand Manan Island (2009); and The Reindeer Botanist: Alf Erling Porsild, 1901-1977 (2012)

- Alison Hawthorne Deming, author, poet, essayist, teacher

- Susan Ingersoll, born on Grand Manan, author, poet, educator, former poetry editor of the St. John's literary journal TickleAce

- Edith Lewis, artist, copywriter, companion of Willa Cather and member of the "Cottage Girls" of Grand Manan

- Lydia Parker, born on Grand Manan, author of children's books focusing on her island upbringing

- Tim Peters, photographer, author of Rhythm of the Tides: The Fisheries of Grand Manan

- Katharine Scherman, American author of non-fiction, including Two Islands: Grand Manan and Sanibel

- Marc Shell, Canadian literary critic, Irving Babbit Comparative and Professor of English at Harvard University; John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur fellow

Scientists and educators

- Eric Allaby, born on Grand Manan; author, painter, scholar, curator, educator, historian, archaeologist and commercial diver. Also served as member of the New Brunswick legislature. His prolific research and documentation of Grand Manan and its shipwrecks helped shape the process of modern marine archaeology.

- Robert M. Cunningham (1919 – 2008), American cloud physicist who studied fog on Kent Island

- Sharon Greenlaw, journalist, philanthropist, educator, and historian; NDP candidate for Charlotte-The Isles riding in 2006 and 2010

- Ernest Wilmot Guptill (1919–1976), born on Grand Manan, received doctorate from McGill University in microwave radiation. Distinguished Faculty, Dalhousie University. Instrumental in the development of radar and sono-buoys.

- Gregory and Nancy McHone, geologists and authors of numerous academic papers and books, including Grand Manan Geology: Excursions in Island Earth History

- Susan Meld Shell, professor, Boston College; author, philosopher, teacher. fellowship recipient, National Endowment for the Humanities

Business

- C. William (Bill) Stanley, founder of Fundy Cable, member of the Stanley family from North Head; received an electrical engineering degree from University of New Brunswick before entering the telecommunications field and becoming a successful cable television pioneer and New Brunswick business leader

Economy

Grand Manan's economy is still dependent upon fishing, aquaculture and tourism. Lobster, herring, scallops and crab are most commonly sought among fishermen. Together with ocean salmon farms, dulsing, rock weed and clam digging, many residents make their living "on the water".

Tourism is growing significantly, providing the island with a highly profitable "green" industry. Whale and bird watching, camping and kayaking are popular activities for tourists. Visitors and retirees often purchase real-estate and remain on the island through the summer months or reside permanently as every necessary amenity exists for people of all ages. Approximately 54% of the island is owned by non-residents. The community is noted for its friendly people, low crime rate, high church membership, quaint villages, and unspoiled sea-scapes. New York architect Michael Zimmer established the Sardine Museum and Herring Hall of Fame.[9]

Demographics

At the 2006 census there were 2,460 people living on Grand Manan, comprising 1,045 households and 700 families. The population density was 42.26 people per square mile (16.31/km²). There were 1,298 housing units at an average density of 22.29/sq mi (8.60/km²). The racial make-up of the island was 99.17% White; and less than 1% Latin American and Aboriginal populations. Those who were third generation or more made up 89% of the population.

There were 1,045 households out of which 23% had children under the age of 18 living with them. Of the 700 census families on the island, 71.42% were married couples living together. The average family size was 2.90.

On the island the population was spread out with 25% age 19 or under; 5% from 20 to 24, 27% from 25 to 44, 25.4% from 45 to 64, and 17.1% at 65 years of age or older. The median age was 40.3 years.

The median income for a family was $48,190. Males had a median income of $32,183 versus $23,106 for females. A full 63% of the population 15 years and older had at least a high school certificate or equivalent, with 22% having at least some college, CEGEP, or university training.

Education

Grand Manan has one Anglophone South K–12 school that services most of Grand Manan Parish called Grand Manan Community School in Grand Harbour.[10]

Access and transportation

Grand Manan is accessible only by daily ferry service, private craft and airplane. Coastal Transport Limited operates two ferries running the Blacks Harbour to Grand Manan Island Ferry route on various schedules throughout the year. The ferry runs daily except on December 25 and January 1. In the summer months when more runs are added, the primary ferry, the Grand Manan Adventure, is augmented with the Grand Manan V. The crossing is about one and half hours—and there is an onboard restaurant with seating, as well as a number of comfortable lounges and external decks accessible to passengers. These large ferries together can handle up to 1000 vehicles per day.

The Grand Manan Island to White Head Island Ferry, currently using the William Frankland Ferry, serves the 220 residents of White Head Island from Ingalls Head on Grand Manan, with a trip of about half an hour. This ferry is free of charge. This ferry replaced the Lady White Head for service on this route.

Airplane service is available to most destinations in the Maritime region and some destinations in the New England States from the Grand Manan Airport. Aerial tours of Grand Manan are available as well. Emergency air transport is provided for medical incidents of a more serious nature. Air service is operated by Manan Air Services and operates no set schedule and typically through request.

Route 776 is the main road on Grand Manan, running on a north-south alignment along the island's eastern coast.

See also

References

- ↑ "Daily Data Report for July 1963". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ↑ "Daily Data Report for January 1890". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ↑ "Seal Cove, New Brunswick". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- ↑ "Grand Manan". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ↑ "Grand Manan SAR CS". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ↑ Walton-1878, Maritime Museum of the Atlantic—On the Rocks Shipwreck Database

- ↑ Jonathan Kellerman, ed. (2008). "The House Across the Way". The best American crime reporting, 2008. New York: Harper Perennial. pp. 53–68. ISBN 0-06-149083-0.

- ↑ "Alfred Thompson Bricher biography". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- ↑ Canadian Geographic 2007 -Page 58 "These weathered structures still line Seal Cove's picturesque harbour, and one contains the Sardine Museum and Herring Hall of Fame, an offbeat tourist attraction established by a wealthy New Yorker to exhibit obsolete fishing equipment as..."

- ↑ Anglophone South, Grand Manan Parish.

Notes

- ↑ 1981–2010 normals are derived from data collected at Seal Cove, however extreme high and low temperatures have been recorded on various parts of the island since 1883. Based on station coordinates, climate data was recorded in the area of Castalia from July 1883 to April 1912 and again from July 1962 to March 1965, at Seal Cove from November 1987 to February 2004 and at Grand Manan Airport from November 2000 to present.

Further reading

- Eric Allaby, Grand Manan: Grand Harbour, Grand Manan Museum, Inc., 64 p., 1984.

- Joshua M. Smith, Borderland Smuggling: Patriots, Loyalists and Illicit Trade in the Northeast, 1783–1820 Gainesville, University Press of Florida, 2006.

- Elaine Ingalls Hogg, Historic Grand Manan: Images of Our Past. Nimbus Publishing, 2007.

- Tim Peters, Rhythm of the Tides, Tim Peter's Publishing, August 2000

- McHone, J.G., 2011, Triassic basin stratigraphy at Grand Manan, New Brunswick, Canada: Atlantic Geology, v. 47, p. 125-137.

- Fyffe, L.R., Grant, R.H., and McHone, J.G., 2011, Bedrock geology of Grand Manan Island (parts of NTS 21 B/1O and B/15): New Brunswick, Department of Natural Resources: Lands, Minerals, and Petroleum Division, Plate 2011-14 (map scale 1:50,000).

- B. V. Miller, S. M. Barr, and R. S. Black, Neoproterozoic and Cambrian U-Pb (zircon) ages from Grand Manan Island, New Brunswick: implications for stratigraphy and northern Appalachian terrane correlations in Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, Volume 44, pp. 911–923, 2007.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Grand Manan Island. |

- Village of Grand Manan

- MANANOOK Grand Manan New Brunswick

- Grand Manan Geology

- Photos of Grand Manan

- Manan Fundy History