Graffito (archaeology)

A graffito (plural "graffiti"), in an archaeological context, is a deliberate mark made by scratching or engraving on a large surface such as a wall. The marks may form an image or writing. The term is not usually used of the engraved decoration on small objects such as bones, which make up a large part of the Art of the Upper Paleolithic, but might be used of the engraved images, usually of animals, that are commonly found in caves, though much less well known than the cave paintings of the same period; often the two are found in the same caves. In archaeology, the term may or may not include the more common modern sense of an "unauthorised" addition to a building or monument. Sgraffito, a decorative technique of partially scratching off a top layer of plaster or some other material to reveal a differently coloured material beneath, is also sometimes known as "graffito".

Listings of graffiti

Basic categories of graffiti in archaeology are:

- Written graffiti, or informal inscriptions.

- Images in graffiti.

- Complex, merged, or multiple category graffiti.

Ancient Egypt graffiti

Modern knowledge of the history of Ancient Egypt was originally derived from inscriptions, literature, (Books of the Dead), pharaonic historical records, and reliefs, from temple statements, from and numerous individual objects whether pharaonic or for the Egyptian citizenry. Twentieth century developments led to finding less common sources of information indicating the intricacies of the interrelationships of the pharaoh, his appointees, and the citizenry.

Three minor sources have helped link the major pieces of interrelationships in Ancient Egypt: ostraca, scarab artifacts, and numerous temple, quarry, etc. sources have helped fill in minor pieces of the complex dealings in Ancient Egypt. The reliefs, and writings with the reliefs, are often supplemented with a graffito, often in hieratic and discovered in locations not commonly seen, like a doorjamb, hallway, entranceway, or the side or reverse of an object.

Late (Roman) Demotic graffiti

Very Late Egyptian Demotic was used only for ostraca, mummy labels, subscriptions to Greek texts, and graffiti. The last dated example of Egyptian Demotic is from the Temple of Isis at Philae, dated to 11 December 452 CE. See Demotic "Egyptian".

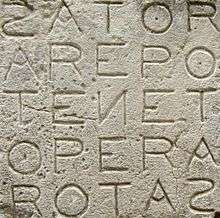

"Christian Magic square graffiti"-(Rotas Square)

The original "Rotas Square" was later made into the 'Sator Square'.

"Sator square"

The Sator square is a Latin graffito found at numerous sites throughout the Roman Empire (e.g. Pompeii, Dura-Europos) and elsewhere (United Kingdom).

It is a palindrome-(theory) which forms a word square that may be read in any direction (with theories). See Sator Arepo Tenet Opera Rotas for alternative details, and Talk:Graffito (archaeology). The reason that the palindrome may only be a theory, is because the square may have to be read boustrophedonically.

The square reads as follows (boustrophedon):

- R...O...T...A...S

- O...P...E...R...A

- T...E...N...E...T

- A...R...E...P...O

- S...A...T...O...R

The square reads: Sator opera tenet; tenet opera sator, and is approximately: "The Great Sower holds in his hand all works; all works the Great Sower holds in his hand." (See: Boustrophedon and the Ceram Ref., pg 30. (Note: reverse direction after the first "tenet", to repeat tenet (then continue boustrophedon).

Four entry points, one per side, renders the reading of the "Magic Square", the "Sator Square": Right, Left, Upwards, or Downwards. (This is why Ceram concluded that it is the christian Sator Square.)

The "Sator Square"– Analysis, Diagrams & "archaeological graffito example":

The Sator Square has to begin at "Rotas", so that it can end at "Sator", basically: "The Great Sower", (i.e. the christian). See: The inscribed square

The "Sator Opera Tenet" square as seen in Oppède, France.

The "Sator Opera Tenet" square as seen in Oppède, France.

Deir el-Bahri religious graffiti

Pilgrims to religious sites left numerous graffiti at the Egyptian site of Deir el-Bahri.[1]

.jpg)

Malta temple graffito: Mnajdra

Malta temple graffito: Mnajdra

Graffiti in ancient Athens

Large quantities of graffiti have been found in Athens during excavations by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens; nearly 850 were catalogued by Mabel Lang in 1976.[2] These include a variety of different types of graffiti, such as abecedaria, kalos inscriptions, insults, marks of ownership, commercial notations, dedications, Christian inscriptions, messages, lists and pictures. They date from the eighth century BC through to the late Roman period.

Medieval graffiti in Britain

There are several types of graffiti found in British buildings dating from the medieval period. There is a wide range of graffiti to be found on medieval buildings and especially in churches. These are some of the most common types:[3]

- Architectural Drawings

- Compass Drawings

- Crosses

- Early text

- Figures

- Heraldry

- Mason's Marks

- Merchant's Marks

- Pentangles

- Ship Graffiti

- Solomon's knot

- VV Symbols

Medieval graffiti is a relatively new area of study with the first full-length work being produced in 1967 by Violet Pritchard.[4] The Norfolk Medieval Graffiti Survey was established in 2010 with the aim of undertaking the first large-scale survey of medieval graffiti in the UK.[5] The survey primarily looks at graffiti dating from the fourteenth to seventeenth centuries. Since 2010 a number of other county based surveys have been set up. These include Kent, Suffolk and Surrey.

The examples below are from Saint Nicholas, the parish church of Blakeney.[6][7]

A ship graffito

A ship graffito Graffito with a decorated capital letter

Graffito with a decorated capital letter A mason's mark

A mason's mark

See also

References

- ↑ Parkinson, R. Cracking Codes, the Rosetta Stone, and Decipherment, Richard Parkinson, with W. Diffie, M. Fischer, and R.S. Simpson, (University of California Press), c. 1999. Section: page 92, "Graffiti" from a temple at Deir el-Bahri. British Museum pieces, EA 1419, 47962, 47963, 47971.

- ↑ M. Lang, 1976. The Athenian Agora Volume XXI: Graffiti and Dipinti. Princeton: The American School of Classical Studies at Athens.

- ↑ Norfolk medieval graffiti survey

- ↑ Suffolk medieval graffiti survey

- ↑ http://www.medieval-graffiti.co.uk/index.html Norfolk Medieval Graffiti Survey

- ↑ Champion, Matthew (2011). "Walls have ears, noses, ships". Cornerstone. 32 (2): 28–32.

- ↑ Norfolk medieval graffiti survey

Further reading

- Ceram, C.W. The March of Archaeology, C.W. Ceram, translated from the German, Richard and Clara Winston, (Alfred A. Knopf, New York), c 1958.

- Champion, Matthew, Medieval Graffiti: The Lost Voices of England's Churches, 2015

- Pritchard, V. English Medieval Graffiti, 1967

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ancient graffiti. |

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Graffito". Encyclopædia Britannica. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 333.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Graffito". Encyclopædia Britannica. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 333.- "The Graffiti of Pompeii". Edinburgh Review. cx: 411–437. October 1859.

- Sator Square, inscribed, Article; the article uses: "Rotas square"