Good-Bye to All That

|

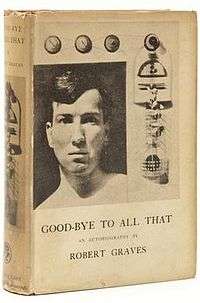

Cover of the first edition | |

| Author | Robert Graves |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Autobiography |

| Publisher | Anchor |

Publication date |

1929 1958 (2nd Edition) |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 368 pp (paperback ed.) |

| ISBN | 0-385-09330-6 |

| OCLC | 21298973 |

| 821/.912 B 20 | |

| LC Class | PR6013.R35 Z5 1990 |

Good-Bye to All That, an autobiography by Robert Graves, first appeared in 1929, when the author was 34 years old. "It was my bitter leave-taking of England," he wrote in a prologue to the revised second edition of 1957, "where I had recently broken a good many conventions".[1] The title may also point to the passing of an old order following the cataclysm of the First World War; the inadequacies of patriotism, the rise of atheism, feminism, socialism and pacifism, the changes to traditional married life, and not least the emergence of new styles of literary expression, are all treated in the work, bearing as they did directly on Graves' life. The unsentimental and frequently comic treatment of the banalities and intensities of the life of a British army officer in the First World War gave Graves fame,[1] notoriety and financial security,[1] but the book's subject is also his family history, childhood, schooling and, immediately following the war, early married life; all phases bearing witness to the "particular mode of living and thinking" that constitute a poetic sensibility.[1]

Laura Riding, Graves' lover, is credited with being a "spiritual and intellectual midwife" to the work.[2]

Wartime experiences

A large part of the book is taken up by his experience of the First World War, in which Graves served as a lieutenant, then captain in the Royal Welch Fusiliers, with the equally famous Siegfried Sassoon. Good-Bye to All That provides a detailed description of trench warfare, including the tragic incompetence of the Battle of Loos and the bitter fighting in the first phase of the Somme Offensive.

Wounds

In the Somme engagement, Graves was wounded while leading his men through the cemetery at Bazentin-le-petit church on 20 July 1916. The wound initially appeared so severe that military authorities erroneously reported to his family that he had died. While mourning his death, Graves's family received word from him that he was alive, and put an announcement to that effect in the newspapers.

Reputed atrocities

The book contains a second-hand description of the killing of German prisoners of war by British troops. Although Graves had not witnessed any and knew of no large massacres, he had been told about a number of incidents in which prisoners had been killed individually or in small groups. Consequently, he was prepared to believe that a proportion of Germans who surrendered never made it to prisoner-of-war camps. "Nearly every instructor in the mess" he wrote, "could quote specific instances of prisoners having been murdered on the way back. The commonest motives were, it seems, revenge for the death of friends or relatives, [and] jealousy of the prisoner's trip to a comfortable prison camp in England".

Post-war trauma

Graves was severely traumatised by his war experience. After being wounded in the lung by a shell blast, he endured a squalid five-day train journey with unchanged bandages. During initial military training in England, he received an electric shock from a telephone that had been hit by lightning, which caused him to stammer and sweat so badly that he did not use a phone again for twelve years. Upon his return home, he describes being haunted by ghosts and nightmares.[3]

Critical responses

Siegfried Sassoon and his friend Edmund Blunden (whose First World War service had been in a different regiment) took umbrage at the contents of the book. Sassoon's complaints mostly related to Graves's depiction of him and his family, whereas Blunden had read the memoirs of J. C. Dunn and found them at odds with Graves in some places.[4] The two men took Blunden's copy of Good-Bye to All That and made marginal notes contradicting some of the text. That copy survives and is held by the New York Public Library.[5] Graves's father, Alfred Perceval Graves, also incensed at some aspects of Graves's book, wrote a riposte to it titled To Return to All That.[6]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Robert Graves (1960). Good-Bye to All That. London: Penguin. p. 7.

- ↑ Richard Perceval Graves, ‘Graves, Robert von Ranke (1895–1985)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, September 2004; online edn, October 2006.

- ↑ "The Other: For Good and For Ill" by Prof. Frank Kersnowski in Trickster's Way, Volume 2, Issue 2, 2003

- ↑ Hugh Cecil, "Edmund Blunden and First World War Writing 1919–36"

- ↑ Anne Garner, "Engaging the Text: Literary Marginalia in the Berg Collection", June 4, 2010. Accessed 6 November 2012.

- ↑ Graves, A. P. (1930). To return to all that: an autobiography. J. Cape. Retrieved 7 December 2014.