Goldfinger (novel)

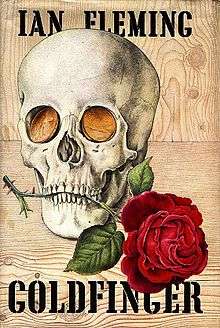

First edition cover, published by Jonathan Cape | |

| Author | Ian Fleming |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Richard Chopping |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Series | James Bond |

| Genre | Spy fiction |

| Publisher | Jonathan Cape |

Publication date | 23 March 1959 |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Preceded by | Dr. No |

| Followed by | For Your Eyes Only |

Goldfinger is the seventh novel in Ian Fleming's James Bond series, first published in the UK by Jonathan Cape on 23 March 1959. Goldfinger originally bore the title The Richest Man in the World and was written in January and February 1958. The story centres on the investigation by MI6 operative James Bond into the gold smuggling activities of Auric Goldfinger, who is also suspected by MI6 of being connected to SMERSH, the Soviet counter-intelligence organisation. As well as establishing the background to the smuggling operation, Bond uncovers a much larger plot, with Goldfinger planning to steal the gold reserves of the United States from Fort Knox.

Fleming developed the James Bond character more in Goldfinger than in the previous six novels, presenting him as a more complex individual, whilst also bringing out a theme of Bond as Saint George. The Saint George theme is echoed by the fact that it is a British agent sorting out an American problem.

In common with Fleming's other Bond stories, he used the names of people he knew, or knew of, throughout his story, including the book's eponymous villain, who was named after British architect Ernő Goldfinger. Upon learning of the use of his name, Goldfinger threatened to sue over the use of the name, before the matter was settled out of court. Fleming had based the actual character on American gold tycoon Charles W. Engelhard, Jr. Fleming also used a number of his own experiences within the book, and the round of golf played with Goldfinger was based upon a tournament in 1957 at the Berkshire Golf Club in which Fleming partnered the Open winner Peter Thomson.

Upon its release, Goldfinger went to the top of the best-seller lists; the novel was broadly well received by the critics, being favourably compared to contemporary version of both Sapper and John Buchan. Goldfinger was serialised as a daily story and as a comic strip in the Daily Express newspaper, before being the third James Bond feature film of the Eon Productions series, released in 1964 and starring Sean Connery as Bond. Most recently, Goldfinger was adapted for BBC Radio with Toby Stephens as Bond and Sir Ian McKellen as Goldfinger.

Plot

Mr Bond, they have a saying in Chicago: "Once is happenstance. Twice is coincidence. The third time it's enemy action." Miami, Sandwich and now Geneva. I propose to wring the truth out of you.

Auric Goldfinger[1]

Fleming structured the novel in three sections—"Happenstance", "Coincidence" and "Enemy action"—which was how Goldfinger described Bond's three seemingly coincidental meetings with him.[1]

- Happenstance

Whilst changing planes in Miami after closing down a Mexican heroin smuggling operation, British Secret Service operative James Bond is asked by Junius Du Pont, a rich American businessman (whom he briefly met and gambled with in Casino Royale), to watch Auric Goldfinger, with whom Du Pont is playing Canasta in order to discover if he is cheating. Bond quickly realises that Goldfinger is indeed cheating with the aid of his female assistant, Jill Masterton, who is spying on DuPont's cards. Bond blackmails Goldfinger into admitting it and paying back DuPont's lost money; he also has a brief affair with Masterton. Back in London, Bond's superior, M, tasks him with determining how Goldfinger is smuggling gold out of the country: M also suspects Goldfinger of being connected to SMERSH and financing their western networks with his gold. Bond visits the Bank of England for a briefing with Colonel Smithers on the methods of gold smuggling.

- Coincidence

Bond contrives to meet and have a round of golf with Goldfinger; Goldfinger attempts to win the golf match by cheating, but Bond turns the tables on him, beating him in the process. He is subsequently invited back to Goldfinger's mansion near Reculver where he narrowly escapes being caught on camera looking over the house. Goldfinger introduces Bond to his factotum, a Korean named Oddjob.

Issued by MI6 with an Aston Martin DB Mark III, Bond trails Goldfinger as he takes his vintage Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost (adapted with armour plating and armour-plated glass) via air ferry to Switzerland, driven by Oddjob. Bond manages to trace Goldfinger to a warehouse in Geneva where he finds that the armour of Goldfinger's car is actually white-gold, cast into panels at his Kent refinery. When the car reaches Goldfinger's factory in Switzerland (Enterprises Auric AG), he recasts the gold from the armour panels into aircraft seats and fits them to the Mecca Charter Airline, in which he holds a large stake. The gold is finally sold in India at a vast profit. Bond foils an assassination attempt on Goldfinger by Jill Masterton's sister, Tilly, to avenge Jill's death at Goldfinger's hands: he had painted her body with gold paint, which killed her. Bond and Tilly attempt to escape when the alarm is raised, but are captured.

- Enemy action

Bond is tortured by Oddjob when he refuses to confess his role in trailing Goldfinger. In a desperate attempt to survive being cut in two by a circular saw, Bond offers to work for Goldfinger, a ruse that Goldfinger initially refuses, but then accepts. Bond and Tilly are subsequently taken to Goldfinger's operational headquarters in a warehouse in New York City. They are put to work as secretaries for a meeting between Goldfinger and several gangsters (including the Spangled Mob and the Mafia), who have been recruited to assist in "Operation Grand Slam" – the stealing of the United States gold reserves from Fort Knox. One of the gang leaders, Helmut Springer, refuses to join the operation and is killed by Oddjob. Learning that the operation includes the killing of the inhabitants of Fort Knox by introducing poison into the water supply, Bond manages to conceal a capsule containing a message into the toilet of Goldfinger's private plane, where he hopes it will be found and sent to Pinkertons, where his friend and ex-counterpart Felix Leiter now works.

Operation Grand Slam commences, and it turns out that Leiter has indeed found and acted on Bond's message. A battle commences, but Goldfinger escapes. Tilly, a lesbian, hopes that one of the gang leaders, Pussy Galore (leader of a gang of lesbian burglars), will protect her, but she is killed by Oddjob. Goldfinger, Oddjob and the mafia bosses all escape in the melee. Bond is drugged before his flight back to England and wakes to find he has been captured by Goldfinger, who has managed to hijack a BOAC jetliner. Bond manages to break a window, causing a depressurisation that blows Oddjob out of the plane; he then fights and strangles Goldfinger. At gunpoint, he forces the crew to ditch in the sea near the Canadian coast, where they are rescued by a nearby weathership.

Characters and themes

The character of Bond was developed more than in the previous novels; academic Jeremy Black considers that, in Goldfinger, Bond "was presented as a complex character".[2] Continuation author Raymond Benson agrees, and sees Goldfinger as a transitional novel, with Bond becoming more human than in previous books and more concerned with what Benson calls "the mortal trappings of life",[3] which manifest itself with the opening chapter of the book as Bond sits in Miami airport and thinks through his fight with and killing of a Mexican thug. Benson also sees that Bond has developed something of a sense of humour in Goldfinger, verbally abusing Oddjob, to Bond's own amusement.[4]

Auric Goldfinger was described by Raymond Benson as "Fleming's most successful villain to date"[4] and Fleming gives him a number of character flaws that are brought out across the novel. Psychologically Goldfinger is warped, possibly because of an inferiority complex brought on by his shortness,[5] in contrast to a number of Fleming's other oversized villains[6] and physically he is odd, with a lack of proportion to his body.[6] As with a number of other villains in the Bond novels, there is an echo of World War II, with Goldfinger employing members of the German Luftwaffe, some Japanese and Koreans.[7] For Operation Grand Slam, Goldfinger used the poison GB, now known as Sarin, which had been discovered by the Nazis.[7] Goldfinger has an obsession with gold to the extent that academic Elizabeth Ladenson says that he is "a walking tautology".[8] Ladenson lists both his family name and his first name as being related to gold ("Auric" is an adjective pertaining to gold); his clothes, hair, car and cat are all gold coloured, or a variant thereof; his Korean servants are referred to by Bond as being "yellow", or yellow-faced";[8] and he paints his women (normally prostitutes) gold before sex.[9]

Elizabeth Ladenson thought the character of Pussy Galore to be "perhaps the most memorable figure in the Bond periphery."[8] Galore was introduced by Fleming in order for Bond to seduce her, thereby proving Bond's masculinity of being able to seduce a lesbian.[10] To some extent the situation also reflected Fleming's own opinions, expressed in the novel as part of Bond's thoughts, where "her sexual confusion is attributable to women's suffrage";[11] in addition, as Fleming himself put it in the book: "Bond felt the sexual challenge all beautiful Lesbians have for men."[12] Ladenson points out that, unlike some Bond girls, Galore's role in the plot is crucial and she is not just there as an accessory: it is her change of heart that allows good to triumph over evil. In doing so, "Goldfinger himself...is a mere obstacle, the dragon to be got rid of before the worthy knight can make off with the duly conquered lady."[8]

As with Ladenson's observation that Bond was being depicted as "the worthy knight", Raymond Benson also identifies the Saint George theme in Goldfinger, which he says has run in all the novels, but is finally stated explicitly in the book as part of Bond's thoughts after Goldfinger reveals he will use an atomic device to open the vault:[13] "Bond sighed wearily. Once more into the breach, dear friend! This time it really was St George and the dragon. And St. George had better get a move on and do something".[14] Jeremy Black notes that the image of the "latter-day St. George [is] again an English, rather than British image."[15]

As with other Bond novels, such as Casino Royale, gambling is a theme, with not only golf as part of the novel, but opening with the canasta game as well. Raymond Benson identified times in the novel when Bond's investigation of Goldfinger was a gamble too and cites Bond tossing a coin to decide on his tactics in relation to his quarry.[16] Once more (as with Live and Let Die and Dr. No) it is Bond the British agent who has to sort out what turns out to be an American problem[17] and this can be seen as Fleming's reaction to the lack of US support over the Suez Crisis in 1956 as well as Bond's warning to Goldfinger not to underestimate the English.[7]

Background

Goldfinger was written in Jamaica at Fleming's Goldeneye estate in January and February 1958 and was the longest typescript Fleming had produced to that time.[18] He initially gave the manuscript the title The Richest Man in the World.[19] Fleming had originally conceived the card game scene as a separate short story but instead used the device for Bond and Goldfinger's first encounter.[20] Similarly, the depressurisation of Goldfinger's plane was another plot device he had intended to use elsewhere, but which found its way into Goldfinger.[20] Some years previously a plane had depressurised over the Lebanon and an American passenger had been sucked out of the window and Fleming, who was not a comfortable airline passenger, had made note of the incident to use it.[20]

As usual in the Bond novels, a number of Fleming's friends or associates had their names used in the novel; the Masterton sisters having their names taken from Sir John Masterman, an MI5 agent and Oxford academic who ran the double cross system during World War II;[21] Alfred Whiting, the golf professional at Royal St George's Golf Club, Sandwich, becoming Alfred Blacking;[21] whilst the Royal St George's Golf Club itself became the Royal St Mark's, for the game between Bond and Goldfinger.[22] In the summer of 1957 Fleming had played in the Bowmaker Pro-Am golf tournament at the Berkshire Golf Club, where he partnered the Open winner Peter Thomson: much of the background went into the match between Bond and Goldfinger.[18] One of Fleming's neighbours in Jamaica, and later his lover, was Blanche Blackwell, mother of Chris Blackwell of Island Records; Fleming used Blanche as the model for Pussy Galore,[23] although the name "Pussy" came from Mrs "Pussy" Deakin, formerly Livia Stela, an SOE agent and friend of his wife's.[21]

Fleming's golf partner, John Blackwell, (a cousin to Blanche Blackwell) was also a cousin by marriage to Ernő Goldfinger and disliked him: it was Blackwell who reminded Fleming of the name. Fleming also disliked what Goldfinger was doing destroying Victorian buildings, replacing them with the architect's modernist designs, particularly a terrace at Goldfinger's own residence at 2 Willow Road.[24] Goldfinger threatened to sue Fleming over the use of the name and, in retaliation, Fleming threatened to add an erratum slip to the book changing the name from Goldfinger to Goldprick and explaining why;[25] the matter was settled out of court after the publishers, Jonathan Cape, agreed to ensure the name Auric was always used in conjunction with Goldfinger.[26] Fleming's golfing friend John Blackwell then became the heroin smuggler at the beginning of the book, with a sister who was a heroin addict.[27]

There were some similarities between Ernő and Auric: both were Jewish immigrants who came to Britain from Eastern Europe in the 1930s[25] and both were Marxists, although they were physically very different.[26] The likely model for Goldfinger was American gold tycoon Charles W. Engelhard, Jr.,[20] who Fleming had met in 1949.[26] Englehard had established a company, the Precious Metals Development Company, which circumvented numerous export restrictions, selling gold ingots directly into Hong Kong.[10] Fleming had reinforced his knowledge of gold by sending a questionnaire to an expert at the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths, one of the Livery Companies of the City of London with a list of queries about gold, its properties and the background of the industry, including smuggling.[28] Fleming himself liked gold enough to commission a gold-plated typewriter from the Royal Typewriter Company,[8] although he never actually used it.[20] In 1995, this machine was purchased by the Bond actor, Pierce Brosnan.[29]

Release and reception

Goldfinger was published on 23 March 1959 in the UK as a hardcover edition by publishers Jonathan Cape; it was 318 pages long and cost fifteen shillings.[30] Richard Chopping again provided the cover art for the first edition: a skull with gold coins for the eyes and a rose in its mouth.[31] The book was dedicated to "gentle reader, William Plomer",[31] the editor of a number of the Fleming novels. Fleming took part in a select number of promotional activities, including appearing on the television programme The Bookman[32] and attending a book signing at Harrods.[33] The novel went straight to the top of the best-seller lists.[34]

Reviews

Goldfinger received more positive reviews than Fleming's previous novel, Dr. No, which had faced widespread criticism in the British media. Writing in The Observer, Maurice Richardson thought that "Mr. Fleming seems to be leaving realism further and further behind and developing only in the direction of an atomic, sophisticated Sapper."[35] Even when leaving reality behind, however, Richardson considers that Fleming, "even with his forked tongue sticking right through his cheek, ... remains maniacally readable".[35] Richardson picked up on two areas relating to the characters of the book, saying that Goldfinger "is the most preposterous specimen yet displayed in Mr. Fleming's museum of super fiends",[35] whilst, referring to the novel's central character, observed that "the real trouble with Bond, from a literary point of view, is that he is becoming more and more synthetic and zombie-ish. Perhaps it is just as well."[35] Writing in The Manchester Guardian, Roy Perrott observed that "Goldfinger...will not let [Bond's] close admirers down".[36] Perrott thought that overall "Fleming is again at his best when most sportingly Buchan-ish as in the motoring pursuit across Europe";[36] he summarised the book by saying that it was "hard to put down; but some of us wish we had the good taste just to try."[36]

The critic writing for The Times thought that Bond was "backed up by sound writing" by Fleming.[37] Although the plot was grandiose, the critic noted that: "it sounds – and is – fantastic; the skill of Mr. Fleming is to be measured by the fact that it is made not to seem so."[37] For The Times Literary Supplement, Michael Robson considered that "a new Bond has emerged from these pages: an agent more relaxed, less promiscuous, less stagily muscular than of yore."[30] Bond was not the only thing that was more relaxed, according to Robson, as "the story, too, is more relaxed."[30] Robson saw this as a positive development, but it did mean that although "there are incidental displays of the virtuosity to which Mr. Fleming has accustomed us, ...the narrative does not slip into top gear until Goldfinger unfolds his plan".[30] The Evening Standard looked at why Bond was a success and listed "the things that make Bond attractive: the sex, the sadism, the vulgarity of money for its own sake, the cult of power, the lack of standards".[20] The Sunday Times called Goldfinger "Guilt-edged Bond",[20] whilst the Manchester Evening News thought that "Only Fleming could have got away with it...outrageously improbable, wickedly funny, wildly exciting".[20]

Even the "avid anti-Bond and an anti-Fleming man",[38] Anthony Boucher, writing for The New York Times appeared to enjoy Goldfinger, saying "the whole preposterous fantasy strikes me as highly entertaining."[31] Meanwhile, the critic for the New York Herald Tribune, James Sandoe considered the book to be "a superlative thriller from our foremost literary magician."[39]

Legacy

Anthony Burgess, in Ninety-nine Novels, cited it as one of the 99 best novels in English since 1939. "Fleming raised the standard of the popular story of espionage through good writing — a heightened journalistic style — and the creation of a government agent — James Bond, 007 — who is sufficiently complicated to compel our interest over a whole series of adventures. A patriotic lecher with a tinge of Scottish puritanism in him, a gourmand and amateur of vodka martinis, a smoker of strong tobacco who does not lose his wind, he is pitted against impossible villains, enemies of democracy, megalomaniacs. Auric Goldfinger is the most extravagant of these. All this is, in some measure, a great joke, but Fleming's passion for plausibility, his own naval intelligence background, and a kind of sincere Manicheism, allied to journalistic efficiency in the management of his recit, make his work rather impressive. The James Bond films, after From Russia With Love, stress the fantastic and are inferior entertainment to the books. It is unwise to disparage the well-made popular. There was a time when Conan Doyle was ignored by the literary annalists even though Sherlock Holmes was evidently one of the great characters of fiction. We must beware of snobbishness."[40]

Adaptations

Daily Express serialisation (1959)

Goldfinger was serialised on a daily basis in the Daily Express newspaper from 18 March 1959 onwards.[41]

Comic strip (1960–1961)

Fleming's original novel was adapted as a daily comic strip which was published in the Daily Express newspaper and syndicated around the world. The adaptation ran from 3 October 1960 to 1 April 1961. The adaptation was written by Henry Gammidge and illustrated by John McLusky.[42] Goldfinger was reprinted in 2005 by Titan Books as part of the Dr. No anthology, which in addition to Dr. No, also included Diamonds Are Forever and From Russia, with Love.[43]

Goldfinger (1964)

In 1964, Goldfinger became the third entry in the James Bond film series. Sean Connery returned as Bond, while German actor Gert Fröbe played Auric Goldfinger.[44] The film was mostly similar to the novel, but Jill and Tilly Masterton (renamed Masterson for the film) have shortened roles and earlier deaths in the story. The plot of the film was also changed from stealing the gold at Fort Knox to irradiating the gold vault with a dirty bomb. [45]

BBC documentary (1973)

The 1973 BBC documentary Omnibus: The British Hero featured Christopher Cazenove playing a number of such title characters (e.g. Richard Hannay and Bulldog Drummond), including James Bond in dramatised scenes from Goldfinger – notably featuring the hero being threatened with the novel's circular saw, rather than the film's laser beam – and Diamonds Are Forever.[46]

Radio adaptation (2010)

Following its successful version of Dr. No, produced in 2008 as a special one-off to mark the centenary of Ian Fleming's birth, Eon Productions allowed a second Bond story to be adapted. On 3 April 2010, BBC Radio 4 broadcast a radio adaptation of Goldfinger with Toby Stephens (who played villain Gustav Graves in Die Another Day) as Bond,[47] Ian McKellen as Goldfinger and Stephens' Die Another Day co-star Rosamund Pike as Pussy Galore. The play was adapted from Fleming's novel by Archie Scottney and was directed by Martin Jarvis.[48]

See also

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Goldfinger |

References

- 1 2 Fleming 2006, p. 222-223.

- ↑ Black 2005, p. 40.

- ↑ Benson 1988, p. 114.

- 1 2 Benson 1988, p. 116.

- ↑ Black 2005, p. 37.

- 1 2 Lindner 2009, p. 40.

- 1 2 3 Black 2005, p. 38.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ladenson, Elizabeth (2003) Missing or empty

|title=(help);|contribution=ignored (help). In: Lindner 2009, chpt. 13 - ↑ Chancellor 2005, p. 116.

- 1 2 Lycett 1996, p. 329.

- ↑ Black 2005, p. 106.

- ↑ Lindner 2009, p. 229.

- ↑ Benson 1988, p. 231.

- ↑ Fleming 2006, ch 18.

- ↑ Black 2005, p. 39.

- ↑ Benson 1988, p. 115.

- ↑ Black 2005, p. 38-39.

- 1 2 Benson 1988, p. 17.

- ↑ Chancellor 2005, p. 128.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Chancellor 2005, p. 129.

- 1 2 3 Chancellor 2005, p. 113.

- ↑ Macintyre 2008, p. 181-183.

- ↑ Thomson, Ian (6 June 2008). "Devil May Care, by Sebastian Faulks, writing as Ian Fleming; For Your Eyes Only, by Ben Macintyre". The Independent. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- ↑ Macintyre 2008, p. 90-91.

- 1 2 Lycett 1996, p. 328.

- 1 2 3 Macintyre 2008, p. 92.

- ↑ John Ezard (3 June 2005). "How Goldfinger nearly became Goldprick". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 1 September 2008.

- ↑ Lycett 1996, p. 327.

- ↑ Welsh, Edward. "Diary". The Times.

- 1 2 3 4 Robson, Michael (3 April 1959). "On the Seamy Side". The Times Literary Supplement. p. 198.

- 1 2 3 Benson 1988, p. 18.

- ↑ Lycett 1996, p. 345.

- ↑ "Tea with an Author". The Observer. 5 April 1959. p. 20.

- ↑ Macintyre 2008, p. 198.

- 1 2 3 4 Richardson, Maurice (22 March 1959). "Sophisticated Sapper". The Observer. p. 25.

- 1 2 3 Perrott, Roy. "Seven days to Armageddon". The Manchester Guardian. p. 8.

- 1 2 "New Fiction". The Times. 26 March 1959. p. 15.

- ↑ Pearson 1967, p. 99.

- ↑ Benson 1988, p. 218.

- ↑ Burgess, Anthony (1984). Ninety-nine Novels. Summit Books. p. 74. ISBN 9780671524074.

- ↑ "James Bond meets Auric Goldfinger". Daily Express. 17 March 1959. p. 1.

- ↑ Fleming, Gammidge & McLusky 1988, p. 6.

- ↑ McLusky et al. 2009, p. 190.

- ↑ "Goldfinger (1964)". Screenonline. British Film Institute. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- ↑ Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 32.

- ↑ Radio Times: 74–79. 6–12 October 1973. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Hemley, Matthew (13 October 2009). "James Bond to return to radio as Goldfinger is adapted for BBC". The Stage Online. Retrieved 19 March 2010.

- ↑ "Goldfinger". Saturday Play. BBC. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

Bibliography

- Pearson, John (1967). The Life of Ian Fleming: Creator of James Bond. London: Jonathan Cape.

- Benson, Raymond (1988). The James Bond Bedside Companion. London: Boxtree Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85283-233-9.

- Fleming, Ian; Gammidge, Henry; McLusky, John (1988). Octopussy. London: Titan Books. ISBN 1-85286-040-5.

- Lycett, Andrew (1996). Ian Fleming. London: Phoenix. ISBN 978-1-85799-783-5.

- Barnes, Alan; Hearn, Marcus (2001). Kiss Kiss Bang! Bang!: the Unofficial James Bond Film Companion. Batsford Books. ISBN 978-0-7134-8182-2.

- Smith, Jim; Lavington, Stephen (2002). Bond Films. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-7535-0709-4.

- Black, Jeremy (2005). The Politics of James Bond: from Fleming's Novel to the Big Screen. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-6240-9.

- Chancellor, Henry (2005). James Bond: The Man and His World. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-6815-2.

- Fleming, Ian (2006). Goldfinger. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-102831-6.

- Macintyre, Ben (2008). For Your Eyes Only. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7475-9527-4.

- Ladenson, Elizabeth (2003). "Pussy Galore". In Lindner, Christoph. The James Bond Phenomenon: a Critical Reader. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-6541-5.

- Lindner, Christoph (2009). The James Bond Phenomenon: a Critical Reader. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-6541-5.

- McLusky, John; Gammidge, Henry; Hern, Anthony; Fleming, Ian (2009). The James Bond Omnibus Vol.1. London: Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-84856-364-3.

External links

- Ian Fleming Bibliography of James Bond 1st Editions