Ixchel

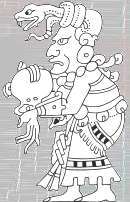

Ixchel or Ix Chel (Mayan: [iʃˈt͡ʃel]) is the 16th-century name of the aged jaguar goddess of midwifery and medicine in ancient Maya culture. She corresponds, more or less, to Toci Yoalticitl "Our Grandmother the Nocturnal Physician", an Aztec earth goddess inhabiting the sweatbath, and is related to another Aztec goddess invoked at birth, viz. Cihuacoatl (or Ilamatecuhtli).[1] In Taube's revised Schellhas-Zimmermann classification of codical deities, Ixchel corresponds to the Goddess O.

Identification

Referring to the early 16th-century, Landa calls Ixchel “the goddess of making children”.[2] He also mentions her as the goddess of medicine, as shown by the following. In the month of Zip, the feast Ihcil Ixchel was celebrated by the physicians and shamans (hechiceros), and divination stones as well as medicine bundles containing little idols of "the goddess of medicine whom they called Ixchel" were brought forward.[3] In the Ritual of the Bacabs, Ixchel is once called 'grandmother'.[4] In their combination, the goddess's two principal qualities (birthing and healing) suggest an analogy with the aged Aztec goddess of midwifery, Tocî Yoalticitl.

Ixchel was already known to the Classical Mayas. As Taube has demonstrated,[5] she corresponds to goddess O of the Dresden Codex, an aged woman with jaguar ears. A crucial piece of evidence in his argument is the so-called "Birth Vase" (Kerr 5113), a Classic Maya container showing a childbirth presided over by various old women, headed by an old jaguar goddess, the codical goddess O; all have weaving implements in their headdresses. On another Classic Maya vase, goddess O is shown acting as a physician, further confirming her identity as Ixchel. The combination of Ixchel with several aged midwives on the Birth Vase recalls the Tz'utujil assembly of midwife goddesses called the "female lords", the most powerful of whom is described as being particularly fearsome.[6]

Meaning of the name

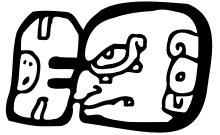

The name Ixchel was in use in 16th-century Yucatán and amongst the Poqom in the Baja Verapaz.[7] Its meaning is not certain. Assuming that the name originated in Yucatán, chel could mean "rainbow".[8] Her glyphic names in the (Post-Classic) codices have two basic forms, one a prefix with the primary meaning of "red" (chak) followed by a pictogram, the other one logosyllabic. Ix Chel's Classic name glyph remains to be identified. It is quite possible that several names were in use to refer to the goddess, and these need not necessarily have included her late Yucatec and Poqom name. Her codical name is now generally rendered as 'Chak Chel'. The designation 'Red Goddess' seems to have a complement in the designation of the young goddess I as 'White Goddess'. The name has also been thought to mean "evening star" or "she of the pale face".

Ixchel and the moon

In the past, Ix Chel was sometimes assumed to be identical to the Classic Maya moon goddess because of the Moon's association with fertility and procreation. Iconographically, however, such an equation is questionable, since what is considered to be the Classic Maya moon goddess, identifiable through her crescent, is always represented as a fertile young woman.[9] On the other hand, the waning moon is often called "Our Grandmother", and not inconceivably, Ixchel might have represented this particular lunar phase associated with the diminishing fertility and eventual dryness of old age. Her codical attribute of an inverted jar could then refer to the jar of the waning moon being emptied. In any case, the moon cycle, taken alone, is of obvious importance to the work of the midwife. The equation of the triad maid, mother, and grandmother with the three basic phases of the moon seems to be quite common among cultures around the world.

Ixchel as an earth and a war goddess

An entwined serpent serves as Ixchel's headdress, crossed bones may adorn her skirt, and instead of human hands and feet, she sometimes has claws. Very similar features are found with Aztec earth goddesses, of whom Tlaltecuhtli, Tocî, and Cihuacoatl were invoked by the midwives. More in particular, the jaguar goddess Ixchel could be conceived as a female warrior, with a gaping mouth suggestive of cannibalism, thus showing her affinity with Cihuacoatl Yaocihuatl 'War Woman'. This manifestation of Cihuacoatl was always hungry for new victims, just as her midwife manifestation helped to produce new babies viewed as captives.

Ixchel as a rain goddess

In the Dresden Codex, goddess O occurs in almanacs dedicated to the rain deities or Chaacs and is stereotypically inverting a water jar. On the famous page 74 originally preceding the New Year pages, her emptying of the water jar replicates the vomiting of water by a celestial dragon. Although this scene is usually understood as the Flood bringing about the world's and the year's end, it might also represent the dramatic onset of the rainy season. The image of the jar filled with rain water may derive from the sac holding the amniotic liquid; turning the jar would then be equivalent to birthgiving.

Mythology

Ixchel figures in a Verapaz myth related by Las Casas, according to which she, together with her spouse, Itzamna, had thirteen sons, two of whom (probably corresponding to the Howler Monkey Gods) created heaven and earth and all that belongs to it.[10] No other myth figuring Ixchel has been preserved. However, her mythology may once have focused on the sweatbath, the place where Maya mothers were wont to go before and after birthgiving.[11] As stated above, the Aztec counterpart to Ixchel as a patron of midwifery, Tocî, was also the goddess of the sweatbath. In myths from Oaxaca, the aged adoptive mother of the Sun and Moon siblings is finally imprisoned in a sweatbath to become its patron deity.[12] Several Maya myths have aged goddesses end up in the same place, in particular the Cakchiquel and Tz'utujil grandmother of Sun and Moon, called B'atzb'al ("Weaving Implement") in Tz'utujil.[13] On the other hand, in Q'eqchi' Sun and Moon myth, an aged Maya goddess (Xkitza) who would otherwise appear to correspond closely to the Oaxacan Old Adoptive Mother, does not appear to be connected to the sweatbath.[14]

Cult of Ixchel

In the early 16th century, Maya women seeking to ensure a fruitful marriage would travel to the sanctuary of Ix Chel on the island of Cozumel, the most important place of pilgrimage after Chichen Itza, off the east coast of the Yucatán peninsula. There, a priest hidden in a large statue would give oracles.[15] To the north of Cozumel is a much smaller island baptized by its Spanish discoverer, Hernández de Córdoba, the 'Island of Women' (Isla Mujeres) "because of the idols he found there, of the goddesses of the country, Ixchel, Ixchebeliax, Ixhunie, Ixhunieta, only vestured from the girdle down, and having the breast covered after the manner of the Indians".[16] On the other side of the peninsula, the head town of the Chontal province of Acalan (Itzamkanac) venerated Ixchel as one its main deities. One of Acalan's coastal settlements was called Tixchel 'At the place of Ixchel'. The Spanish conqueror, Hernán Cortés, tells us about another place in Acalan where unmarried young women were sacrificed to a goddess in whom "they had much faith and hope", possibly again Ix Chel.[17]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Category:Ixchel. |

Notes

- ↑ Miller and Taube 1993: 101

- ↑ Tozzer 1941: 129

- ↑ Tozzer 1941: 154

- ↑ Roys 1965: 53

- ↑ Taube 1994:650-685

- ↑ Tarn and Prechtel 1986: 179

- ↑ Poqom, Miles 1957: 748

- ↑ Eric Groves (2009). Baby Names That Go Together: From Lily, Rose, and Violet to Finn and Fay - Sibling Names that Mix and Match in a Perfect Way (illustrated ed.). Adams Media. p. 136. ISBN 1440514267. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- ↑ cf. Miller and Taube 1993: 101

- ↑ Coe 1977: 329

- ↑ For a full background, see Groark 1997

- ↑ cf. Thompson 1970:358-359

- ↑ Tarn and Prechtel 1986:177, 184n16

- ↑ Thompson 1970:355-356

- ↑ Tozzer 1941: 109-110n500

- ↑ Tozzer 1941: 9-10

- ↑ Ixchel in Acalan, see Scholes and Roys 1968: 57; 383, 395

Bibliography and references

- Coe, Michael (1977). "Supernatural Patrons of Maya Scribes and Artists." In N. Hammond. Social Process in Maya Prehistory. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 327–347.

- Groark, Kevin P., To Warm the Blood, To Warm the Flesh: The Role of the Steambath in Highland Maya (Tzotzil-Tzeltal) Ethnomedicine. Journal of Latin American Lore 20-1 (1997): 3-96.

- Miles, S.W., The Sixteenth-Century Pokom-Maya. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society 1957.

- Miller, Mary, and Karl Taube, An Illustrated Dictionary of The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya. Thames and Hudson 1993.

- Roys, Ralph L., Ritual of the Bacabs. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 1965.

- Scholes, France V., and Ralph L. Roys, The Maya Chontal Indians of Acalan-Tixchel. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 1968.

- Tarn, Nathaniel, and Martin Prechtel, Constant Inconstancy. The Feminine Principle in Atiteco Mythology. In Gary Gossen ed., Symbol and Meaning beyond the Closed Community. Essays in Mesoamerican Ideas. New York: State University of New York at Albany 1986.

- Taube, Karl, The Birth Vase: Natal Imagery in Ancient Maya Myth and Ritual. In Justin Kerr, ed., The Maya Vase Book: A Corpus of Rollout Photographs of Maya Vases, Volume 4. New York: Kerr Associates 1994.

- J.E.S. Thompson, Maya History and Religion. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 1970.

- Tozzer, Alfred, Landa's Relación de las Cosas de Yucatán, a Translation. 1941.