Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency

| Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency | |

|---|---|

| |

| Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

| ICD-10 | D55.0 |

| ICD-9-CM | 282.2 |

| OMIM | 305900 |

| DiseasesDB | 5037 |

| MedlinePlus | 000528 |

| eMedicine | med/900 |

| Patient UK | Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency |

| MeSH | D005955 |

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PD deficiency), also known as favism (after the fava bean), is an X-linked recessive inborn error of metabolism that predisposes to hemolysis (spontaneous destruction of red blood cells) and resultant jaundice in response to a number of triggers, such as certain foods, illness, or medication. It is particularly common in people of Mediterranean and African origin. The condition is characterized by abnormally low levels of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, an enzyme involved in the pentose phosphate pathway that is especially important in the red blood cell. G6PD deficiency is the most common human enzyme defect.[1] There is no specific treatment, other than avoiding known triggers. In the United States, no genetic screening of prospective parents is recommended, as the symptoms only show in part of the carriers and when that is the case, they can be prevented or controlled, and as a result the disease generally has no impact on the lifespan of those affected.[2] However, globally G6PD deficiency has resulted in 4,100 deaths in 2013 and 3,400 deaths in 1990.[3]

Carriers of the G6PD allele appear to be protected to some extent against malaria, and in some cases affected males have shown complete immunity to the disease. This accounts for the persistence of the allele in certain populations in that it confers a selective advantage.[4]

Signs and symptoms

Most individuals with G6PD deficiency are asymptomatic.

Symptomatic patients are almost exclusively male, due to the X-linked pattern of inheritance, but female carriers can be clinically affected due to unfavorable lyonization, where random inactivation of an X-chromosome in certain cells creates a population of G6PD-deficient red blood cells coexisting with normal red cells. A typical female with one affected X chromosome will show the deficiency in approximately half of her red blood cells. However, in rare cases, including double X deficiency, the ratio can be much more than half, making the individual almost as sensitive as a male.

Abnormal red blood cell breakdown (hemolysis) in G6PD deficiency can manifest in a number of ways, including the following:

- Prolonged neonatal jaundice, possibly leading to kernicterus (arguably the most serious complication of G6PD deficiency)

- Hemolytic crises in response to:

- Illness (especially infections)

- Certain drugs (see below)

- Certain foods, most notably broad beans

- Certain chemicals

- Diabetic ketoacidosis

- Very severe crises can cause acute kidney failure

Favism may be formally defined as a hemolytic response to the consumption of broad beans. All individuals with favism show G6PD deficiency. However, not all individuals with G6PD deficiency show favism. Favism is known to be more prevalent in infants and children, and G6PD genetic variant can influence chemical sensitivity.[5] Other than this, the specifics of the chemical relationship between favism and G6PD are not well understood.

6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (6PGD) deficiency has similar symptoms and is often mistaken for G6PD deficiency, as the affected enzyme is within the same pathway, however these diseases are not linked and can be found within the same patient.

Genetic cause

Two variants (G6PD A− and G6PD Mediterranean) are the most common in human populations. G6PD A− has an occurrence of 10% of Africans and African-Americans while G6PD Mediterranean is prevalent in the Middle East. The known distribution of the disease is largely limited to people of Mediterranean origins (Spaniards, Italians, Greeks, Armenians, Jews and other Semitic peoples).[6] Both variants are believed to stem from a strongly protective effect against Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax malaria.[7] It is particularly frequent in the Kurdish population (1 in 2 males have the condition and the same rate of females are carriers).[2] It is also common in African American, Saudi, Sardinian males, some African populations, and Asian groups.[2]

All mutations that cause G6PD deficiency are found on the long arm of the X chromosome, on band Xq28. The G6PD gene spans some 18.5 kilobases.[8] The following variants and mutations are well-known and described:

Table 1. Descriptive mutations and variants Variants or mutations Gene Protein Designation Short name Isoform

G6PD-ProteinOMIM-Code Type Subtype Position Position Structure change Function change G6PD-A(+) Gd-A(+) G6PD A +305900.0001 Polymorphism nucleotide A→G 376

(Exon 5)126 Asparagine→Aspartic acid (ASN126ASP) No enzyme defect (variant) G6PD-A(-) Gd-A(-) G6PD A +305900.0002 Substitution nucleotide G→A 376

(Exon 5)

and

20268

and

126Valine→Methionine (VAL68MET)

Asparagine→Aspartic acid (ASN126ASP)G6PD-Mediterranean Gd-Med G6PD B +305900.0006 Substitution nucleotide C→T 563

(Exon 6)188 Serine→Phenylalanine (SER188PHE) Class II G6PD-Canton Gd-Canton G6PD B +305900.0021 Substitution nucleotide G→T 1376 459 Arginine→Leucine (ARG459LEU) Class II G6PD-Chatham Gd-Chatham G6PD +305900.0003 Substitution nucleotide G→A 1003 335 Alanine→Threonine (ALA335THR) Class II G6PD-Cosenza Gd-Cosenza G6PD B +305900.0059 Substitution nucleotide G→C 1376 459 Arginine→Proline (ARG459PRO) G6PD-activity <10%, thus high portion of patients. G6PD-Mahidol Gd-Mahidol G6PD +305900.0005 Substitution nucleotide G→A 487

(Exon 6)163 Glycine→Serine (GLY163SER) Class III G6PD-Orissa Gd-Orissa G6PD +305900.0047 Substitution nucleotide C→G 131 44 Alanine→Glycine (ALA44GLY) NADP-binding place affected. Higher stability than other variants. G6PD-Asahi Gd-Asahi G6PD A- +305900.0054 Substitution nucleotide (several) A→G

±

G→A376

(Exon 5)

202126

68Asparagine→Aspartic acid (ASN126ASP)

Valine→Methionine (VAL68MET)Class III.

Triggers

Carriers of the underlying mutation do not show any symptoms unless their red blood cells are exposed to certain triggers, which can be of three main types:

- foods (fava beans is one of them),

- medicines and other chemicals (see below), or

- stress from a bacterial or viral infection.[2]

In order to avoid the hemolytic anemia, G6PD carriers have to avoid a large number of drugs and foods.[2] List of such "triggers" can be obtained from medical providers.[2]

Drugs

Many substances are potentially harmful to people with G6PD deficiency. Variation in response to these substances makes individual predictions difficult. Antimalarial drugs that can cause acute hemolysis in people with G6PD deficiency include primaquine, pamaquine, and chloroquine. There is evidence that other antimalarials may also exacerbate G6PD deficiency, but only at higher doses. Sulfonamides (such as sulfanilamide, sulfamethoxazole, and mafenide), thiazolesulfone, methylene blue, and naphthalene should also be avoided by people with G6PD deficiency as they antagonize folate synthesis, as should certain analgesics (such as phenazopyridine and acetanilide) and a few non-sulfa antibiotics (nalidixic acid, nitrofurantoin, isoniazid, dapsone, and furazolidone).[1][8][9] Henna has been known to cause hemolytic crisis in G6PD-deficient infants.[10] Rasburicase is also contraindicated in G6PD deficiency.

Pathophysiology

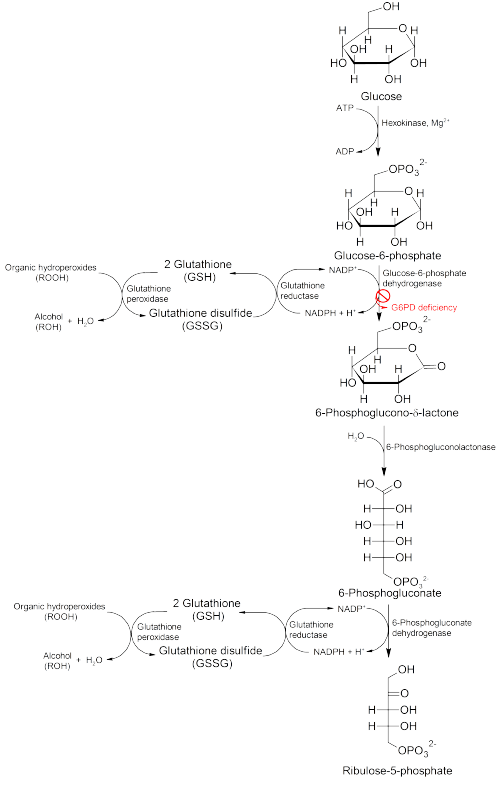

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) is an enzyme in the pentose phosphate pathway (see image, also known as the HMP shunt pathway). G6PD converts glucose-6-phosphate into 6-phosphoglucono-δ-lactone and is the rate-limiting enzyme of this metabolic pathway that supplies reducing energy to cells by maintaining the level of the reduced form of the co-enzyme nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH). The NADPH in turn maintains the supply of reduced glutathione in the cells that is used to mop up free radicals that cause oxidative damage.

The G6PD / NADPH pathway is the only source of reduced glutathione in red blood cells (erythrocytes). The role of red cells as oxygen carriers puts them at substantial risk of damage from oxidizing free radicals except for the protective effect of G6PD/NADPH/glutathione.

People with G6PD deficiency are therefore at risk of hemolytic anemia in states of oxidative stress. Oxidative stress can result from infection and from chemical exposure to medication and certain foods. Broad beans, e.g., fava beans, contain high levels of vicine, divicine, convicine and isouramil, all of which create oxidants - Eur. J. Biochem. 127, 405-409 (1982).

When all remaining reduced glutathione is consumed, enzymes and other proteins (including hemoglobin) are subsequently damaged by the oxidants, leading to cross-bonding and protein deposition in the red cell membranes. Damaged red cells are phagocytosed and sequestered (taken out of circulation) in the spleen. The hemoglobin is metabolized to bilirubin (causing jaundice at high concentrations). The red cells rarely disintegrate in the circulation, so hemoglobin is rarely excreted directly by the kidney, but this can occur in severe cases, causing acute renal failure.

Deficiency of G6PD in the alternative pathway causes the buildup of glucose and thus there is an increase of advanced glycation endproducts (AGE). The deficiency also reduces the amount of NADPH, which is required for the formation of nitric oxide (NO). The high prevalence of diabetes mellitus type 2 and hypertension in Afro-Caribbeans in the West could be directly related to the incidence of G6PD deficiency in those populations.[11]

Although female carriers can have a mild form of G6PD deficiency (dependent on the degree of inactivation of the unaffected X chromosome – see lyonization), homozygous females have been described; in these females there is co-incidence of a rare immune disorder termed chronic granulomatous disease (CGD).

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is generally suspected when patients from certain ethnic groups (see epidemiology) develop anemia, jaundice and symptoms of hemolysis after challenges from any of the above causes, especially when there is a positive family history.

Generally, tests will include:

- Complete blood count and reticulocyte count; in active G6PD deficiency, Heinz bodies can be seen in red blood cells on a blood film;

- Liver enzymes (to exclude other causes of jaundice);

- Lactate dehydrogenase (elevated in hemolysis and a marker of hemolytic severity)

- Haptoglobin (decreased in hemolysis);

- A "direct antiglobulin test" (Coombs' test) – this should be negative, as hemolysis in G6PD is not immune-mediated;

When there are sufficient grounds to suspect G6PD, a direct test for G6PD is the "Beutler fluorescent spot test", which has largely replaced an older test (the Motulsky dye-decolouration test). Other possibilities are direct DNA testing and/or sequencing of the G6PD gene.

The Beutler fluorescent spot test is a rapid and inexpensive test that visually identifies NADPH produced by G6PD under ultraviolet light. When the blood spot does not fluoresce, the test is positive; it can be falsely negative in patients who are actively hemolysing. It can therefore only be done 2–3 weeks after a hemolytic episode.

When a macrophage in the spleen identifies a RBC with a Heinz body, it removes the precipitate and a small piece of the membrane, leading to characteristic "bite cells". However, if a large number of Heinz bodies are produced, as in the case of G6PD deficiency, some Heinz bodies will nonetheless be visible when viewing RBCs that have been stained with crystal violet. This easy and inexpensive test can lead to an initial presumption of G6PD deficiency, which can be confirmed with the other tests.

Classification

The World Health Organization classifies G6PD genetic variants into five classes, the first three of which are deficiency states.[12]

- Class I: Severe deficiency (<10% activity) with chronic (nonspherocytic) hemolytic anemia

- Class II: Severe deficiency (<10% activity), with intermittent hemolysis

- Class III: Mild deficiency (10-60% activity), hemolysis with stressors only

- Class IV: Non-deficient variant, no clinical sequelae

- Class V: Increased enzyme activity, no clinical sequelae

Treatment

The most important measure is prevention – avoidance of the drugs and foods that cause hemolysis. Vaccination against some common pathogens (e.g. hepatitis A and hepatitis B) may prevent infection-induced attacks.[13]

In the acute phase of hemolysis, blood transfusions might be necessary, or even dialysis in acute kidney failure. Blood transfusion is an important symptomatic measure, as the transfused red cells are generally not G6PD deficient and will live a normal lifespan in the recipient's circulation. Those affected should avoid drugs such as aspirin.

Some patients may benefit from removal of the spleen (splenectomy),[14] as this is an important site of red cell destruction. Folic acid should be used in any disorder featuring a high red cell turnover. Although vitamin E and selenium have antioxidant properties, their use does not decrease the severity of G6PD deficiency.

Epidemiology

G6PD deficiency is the most common human enzyme defect, being present in more than 400 million people worldwide.[15] G6PD deficiency resulted in 4,100 deaths in 2013 and 3,400 deaths in 1990.[3] African, Middle Eastern and South Asian people are affected the most, including those who have these ancestries.[16] A side effect of this disease is that it confers protection against malaria,[17] in particular the form of malaria caused by Plasmodium falciparum, the most deadly form of malaria. A similar relationship exists between malaria and sickle-cell disease. One theory to explain this is that cells infected with the Plasmodium parasite are cleared more rapidly by the spleen. This phenomenon might give G6PD deficiency carriers an evolutionary advantage by increasing their fitness in malarial endemic environments. In vitro studies have shown that the Plasmodium falciparum is very sensitive to oxidative damage. This is the basis for another theory, that is that the genetic defect confers resistance due to the fact that the G6PD-deficient host has a higher level of oxidative agents that, while generally tolerable by the host, are deadly to the parasite.[18]

Prognosis

G6PD-deficient individuals do not appear to acquire any illnesses more frequently than other people, and may have less risk than other people for acquiring ischemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease.[19]

Culture

In both legend and mythology, Favism has been known since antiquity. The priests of various Greco-Roman era cults were forbidden to eat or even mention beans, and Pythagoras had a strict rule that to join the society of the Pythagoreans one had to swear off beans.[20] This ban was supposedly because beans resembled male genitalia, but it is possible that this was because of a belief that beans and humans were created from the same material.[21]

Research history

The modern understanding of the condition began with the analysis of patients who exhibited sensitivity to primaquine.[22] The discovery of G6PD deficiency relied heavily upon the testing of prisoner volunteers at Illinois State Penitentiary, a type of studies which today cannot be performed. When some prisoners were given the drug primaquine, some developed hemolytic anemia but others did not. After studying the mechanism through Cr51 testing, it was conclusively shown that the hemolytic effect of primaquine was due to an intrinsic defect of erythrocytes.[23]

References

- 1 2 Frank JE (October 2005). "Diagnosis and management of G6PD deficiency". Am Fam Physician. 72 (7): 1277–82. PMID 16225031.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydogenase Deficiency (G6PD) on The Jewish Genetic Disease Consortium (JGDC) website

- 1 2 GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators (17 December 2014). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013.". Lancet. 385: 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604

. PMID 25530442.

. PMID 25530442. - ↑ Lewis, Ricki (1997). Human Genetics. Chicago, IL: Wm. C. Brown. pp. 247–248. ISBN 0-697-24030-4.

- ↑ Luzzatto, L. "GLUCOSE-6-PHOSPHATE DEHYDROGENASE DEFICIENCY." Advanced Medicine-Twelve: Proceedings of a Conference Held at the Royal College of Physicians of London, 11–14 February 1985. Vol. 21. Churchill Livingstone, 1986.

- ↑ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/202897/favism

- ↑ Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson; Aster, Jon (2009-05-28). Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, Professional Edition: Expert Consult - Online (Robbins Pathology) (Kindle Locations 33351-33354). Elsevier Health. Kindle Edition.

- 1 2 Warrell, David A.; Timothy M. Cox; John D. Firth; Edward J. Benz (2005). Oxford Textbook of Medicine, Volume Three. Oxford University Press. pp. 720–725. ISBN 0-19-857013-9.

- ↑ A comprehensive list of drugs and chemicals that are potentially harmful in G6PD deficiency can be found in Beutler E (December 1994). "G6PD deficiency". Blood. 84 (11): 3613–36. PMID 7949118..

- ↑ Raupp P, Hassan JA, Varughese M, Kristiansson B (2001). "Henna causes life threatening haemolysis in glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency". Arch. Dis. Child. 85 (5): 411–2. doi:10.1136/adc.85.5.411. PMC 1718961

. PMID 11668106.

. PMID 11668106. - ↑ Gaskin RS, Estwick D, Peddi R (2001). "G6PD deficiency: its role in the high prevalence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus". Ethnicity & disease. 11 (4): 749–54. PMID 11763298.

- ↑ WHO Working Group (1989). "Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency.". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 67 (6): 601–11. PMID 2633878.

- ↑ Monga A, Makkar RP, Arora A, Mukhopadhyay S, Gupta AK (July 2003). "Case report: Acute hepatitis E infection with coexistent glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency". Can J Infect Dis. 14 (4): 230–1. PMC 2094938

. PMID 18159462.

. PMID 18159462. - ↑ Hamilton JW, Jones FG, McMullin MF (August 2004). "Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase Guadalajara – a case of chronic non-spherocytic haemolytic anaemia responding to splenectomy and the role of splenectomy in this disorder". Hematology. 9 (4): 307–9. doi:10.1080/10245330410001714211. PMID 15621740.

- ↑ Cappellini MD, Fiorelli G (January 2008). "Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency". Lancet. 371 (9606): 64–74. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60073-2. PMID 18177777.

- ↑ G-6-PD FAQ section

- ↑ Mehta A, Mason PJ, Vulliamy TJ (2000). "Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency". Baillieres Best Pract. Res. Clin. Haematol. 13 (1): 21–38. PMID 10916676.

- ↑ Nelson, David L.; Cox, Michael M. (13 February 2013). Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry (6th ed.). Basingstoke, England: Macmillan Higher Education. p. 576. ISBN 978-1-4641-0962-1.

- ↑ thefreedictionary.com > glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency citing: Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine. Copyright 2008

- ↑ Simoons, F.J. (1996-08-30). "8". Plants of Life, Plants of Death. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 216. ISBN 0299159043.

- ↑ Rendall, Steven; Riedweg, Christoph (2005). Pythagoras: his life, teaching, and influence. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-4240-0.

- ↑ Alving AS, Carson PE, Flanagan CL, Ickes CE (September 1956). "Enzymatic deficiency in primaquine-sensitive erythrocytes" (PDF). Science. 124 (3220): 484–5. Bibcode:1956Sci...124..484C. doi:10.1126/science.124.3220.484-a. PMID 13360274.

- ↑ Beutler E (January 2008). "Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency: a historical perspective". Blood. 111 (1): 16–24. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-04-077412. PMID 18156501.

External links

- G6PD Deficiency Association

- G6PD Deficiency & Favism Website

- The G6PD homepage

- The G6PDdb – genetic and structural information database about glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency

- A FAQ page on G6PD Deficiency by R&D Diagnostics

- Family Practice Notebook/G6PD Deficiency (Favism)

- The Most Common Disease You've Never Heard Of, by Randall Amster, The Huffington Post, July 22, 2009.

- Rare Anemias Foundation