Glendalough

| Gleann Dá Loch | |

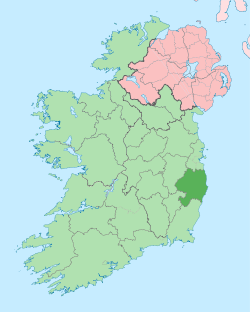

|

| |

Location within Ireland | |

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Order | Celtic Christianity |

| Established | 6th century |

| Disestablished | 1398 |

| Diocese |

Glendalough (to 1185) Dublin and Glendalough (1185–1398) |

| People | |

| Founder(s) | Saint Kevin |

| Architecture | |

| Status | Inactive |

| Style | Irish monastic, Romanesque |

| Site | |

| Location | County Wicklow |

| Coordinates | 53°00′37″N 6°19′39″W / 53.010278°N 6.3275°W |

| Visible remains | Round tower, gateway, cathedral, several churches |

| Public access | yes |

| Website |

www |

Glendalough (/ˌɡlɛndəˈlɒx/; Irish: Gleann Dá Loch, meaning "Valley of two lakes") is a glacial valley in County Wicklow, Ireland, renowned for an Early Medieval monastic settlement founded in the 6th century by St Kevin.

History

Kevin, a descendant of one of the ruling families in Leinster, studied as a boy under the care of three holy men, Eoghan, Lochan, and Eanna. During this time, he went to Glendalough. He was to return later, with a small group of monks to found a monastery where the 'two rivers form a confluence'. Kevin's writings discuss his fighting "knights" at Glendalough; scholars today believe this refers to his process of self-examination and his personal temptations.[1] His fame as a holy man spread and he attracted numerous followers. He died in about 618. For six centuries afterwards, Glendalough flourished and the Irish Annals contain references to the deaths of abbots and raids on the settlement.[2]

Around 1042, oak timber from Glendalough was used to build the second longest (30 m) Viking longship ever recorded. A modern replica of that ship was built in 2004 and is currently located in Roskilde, Denmark.[3]

At the Synod of Rath Breasail in 1111, Glendalough was designated as one of the two dioceses of North Leinster.

The Book of Glendalough was written there about 1131.

St. Laurence O'Toole, born in 1128, became Abbot of Glendalough and was well known for his sanctity and hospitality. Even after his appointment as Archbishop of Dublin in 1162, he returned occasionally to Glendalough, to the solitude of St. Kevin's Bed. He died in Eu, in Normandy in 1180.[2]

In 1214, the dioceses of Glendalough and Dublin were united. From that time onwards, the cultural and ecclesiastical status of Glendalough diminished. The destruction of the settlement by English forces in 1398 left it a ruin but it continued as a church of local importance and a place of pilgrimage.

Glendalough features on the 1598 map "A Modern Depiction of Ireland, One of the British Isles" by Abraham Ortelius as "Glandalag".

Descriptions of Glendalough from the 18th and 19th centuries include references to occasions of "riotous assembly" on the feast of St. Kevin on 3 June.[2]

The present remains in Glendalough tell only a small part of its story. The monastery in its heyday included workshops, areas for manuscript writing and copying, guest houses, an infirmary, farm buildings and dwellings for both the monks and a large lay population. The buildings which survive probably date from between the 10th and 12th centuries.[2]

Titular see

Glendalough is currently a titular see in the Catholic Church. It is used for bishops who hold no ordinary power of their own and thus are titular bishops.[4]

Titular bishops

- Raymond D'Mello (20 December 1969 -13 December 1973)

- Marian Przykucki (12 December 1973 - 15 June 1981)

- Donal Murray (4 March 1982 - 10 February 1996)

- Diarmuid Martin (5 December 1998 - 14 October 2014 )

- Guy Sansaricq (6 June 2006 - 16 August 2014 )[4]

Annalistic references

See Annals of Inisfallen (AI)

- AI800.2 Minndenach, abbot of Glenn dá Locha, rested.

- AI809.2 Échtbrann, abbot of Glenn dá Locha, [rested].

- AI1003.6 Dúnchad Ua Mancháin, abbot of Glenn dá Locha, rested.

Monuments in the Lower Valley

The Gateway

The Gateway to the monastic city of Glendalough is one of the most important monuments, now totally unique in Ireland. It was originally two-storeyed with two fine, granite arches. The antae or projecting walls at each end suggest that it had a timber roof. Inside the gateway, in the west wall, is a cross-inscribed stone. This denoted sanctuary, the boundary of the area of refuge. The paving of the causeway in the monastic city is still preserved in part but very little remains of the enclosure wall.[2]

The Round Tower

This fine tower, built of mica-slate interspersed with granite is about 30 metres high, with an entrance 3.5 metres from the base. The conical roof was rebuilt in 1876 using the original stones. The tower originally had six timber floors, connected by ladders. The four storeys above entrance level are each lit by a small window; while the top storey has four windows facing the cardinal compass points. Round towers, landmarks for approaching visitors, were built as bell towers, but also served on occasion as store-houses and as places of refuge in times of attack.[2]

The Cathedral

The largest and most imposing of the buildings at Glendalough, the cathedral had several phases of construction, the earliest, consisting of the present nave with its antae. The large mica-schist stones which can be seen up to the height of the square-headed west doorway were re-used from an earlier smaller church. The chancel and sacristy date from the late 12th and early 13th centuries. The chancel arch and east window were finely decorated, though many of the stones are now missing. The north doorway to the nave also dates from this period. Under the southern window of the chancel is an ambry or wall cupboard and a piscina, a basin used for washing the sacred vessels. A few metres south of the cathedral an early cross of local granite, with an unpierced ring, is commonly known as St. Kevin's Cross.[2]

The Priests' House

Almost totally reconstructed from the original stones, based on a 1779 sketch made by Beranger, the Priests' House is a small Romanesque building, with a decorative arch at the east end. It gets its name from the practice of interring priests there in the 18th and 19th centuries. Its original purpose is unknown although it may have been used to house relics of St. Kevin.[2]

St. Kevin's Church or "Kitchen"

This stone-roofed building originally had a nave only, with entrance at the west end and a small round-headed window in the east gable. The upper part of the window can be seen above what became the chancel arch, when the chancel (now missing) and the sacristy were added later. The steep roof, formed of overlapping stones, is supported internally by a semi-circular vault. Access to the croft or roof chamber was through a rectangular opening towards the western end of the vault. The church also had a timber first floor. The belfry with its conical cap and four small windows rises from the west end of the stone roof in the form of a miniature round tower.[2]

St. Ciarán's (Kieran's) Church

The remains of this nave-and-chancel church were uncovered in 1875. The church probably commemorates St. Ciarán (Kieran), the founder of Clonmacnoise, a monastic settlement that had associations with Glendalough during the 10th century.[2]

St. Mary's or Our Lady's Church

One of the earliest and best constructed of the churches, St. Mary's or Our Lady's Church consists of a nave with a later chancel. Its granite west doorway with an architrave, has inclined jambs and a massive lintel. The under-side of the lintel is inscribed with an unusual saltire or x-shaped cross. The East window is round-headed, with a hood moulding and two very worn carved heads on the outside.[2]

Trinity Church

A simple nave-and-chancel church, with a fine chancel arch. Trinity Church is beside the main road. A square-headed doorway in the west gable leads into a later annexe, possibly a sacristy. A round tower or belfry was constructed over a vault in this chamber. This fell in a storm in 1818. The doorway inserted in the south wall of the nave also dates from this period. Projecting corbels at the gables would have carried the verge timbers of the roof.[2]

St. Saviour's Church

The most recent of the Glendalough churches, St. Saviour's was built in the 12th century, probably at the time of St. Laurence O'Toole. The nave and chancel with their fine decorate stones were restored in the 1870s using stones found on the site. The Romanesque chancel arch has three orders, with highly ornamented capitals. The east window has two round-headed lights. Its decorated features include a serpent, a lion, and two birds holding a human head between their beaks. A staircase in the eastern wall leading from an adjoining domestic building would have given access to a room over the chancel.[2]

Monuments near the Upper Lake

Reefert Church

Situated in a grove of trees, this nave-and-chancel church dates from around 1100. Most of the surrounding walls are modern. The name derives from Righ Fearta, the burial place of the kings. The church, built in simple style, has a granite doorway with sloping jambs and flat lintel and a granite chancel arch. The projecting corbels at each gable carried verge timbers for the roof. East of the church are two crosses of note, one with an elaborate interlace pattern. On the other side of the Poulanass River, close to Reefert are the remains of another small church.[2]

St. Kevin's Cell

Built on a rocky spur over the lake, this stone structure was 3.6 metres in diameter with walls 0.9 metres thick and a doorway on the east side. Only the foundations survive today and it is possible that the cell had a stone-corbelled roof, similar to the beehive huts on Skellig Michael, County Kerry.[2]

The "Caher"

This stone-walled circular enclosure on the level ground between the two lakes is 20 metres in diameter and is of unknown date. Close by, are several crosses, apparently used as stations on the pilgrim's route.[2]

Temple-na-Skellig and St. Kevin's Bed

This small rectangular church on the southern shore of the Upper Lake is accessible only by boat, via a series of steps from the landing stage. West of the church is a raised platform with stone enclosure walls, where dwelling huts probably stood. The church, partly rebuilt in the 12th century, has a granite doorway with inclined jambs. At the east gable is an inscribed Latin Cross together with several plain grave slabs and three small crosses. Close by is St. Kevin's Bed, a cave in the rock face about 8 metres above the level of the Upper Lake and reputedly a retreat for St. Kevin and later for St. Laurence O'Toole. Partly man-made, it runs back 2 metres into the rock.[2]

Geography

The valley was formed during the last ice age by a glacier which left a moraine across the valley mouth. The Poulanass river, which plunges into the valley from the south, created a delta, which eventually divided the original lake in two.[5]

Vegetation and natural resources

Glendalough is surrounded by semi-natural oak woodland. Much of this was formerly coppiced (cut to the base at regular intervals) to produce wood, charcoal and bark. In the springtime, the oakwood floor is carpeted with a display of bluebells, wood sorrel and wood anemones. Other common plants are woodrush, bracken, polypody fern and various species of mosses. The understorey is largely of holly, hazel and mountain ash.

At the west end of the Upper Lake lie the ruins of an abandoned miners' village normally accessible only by foot. The mining of lead took place here from 1850 until about 1957 but the mines in the valley of Glendalough were smaller and less important than those around the Glendasan Valley, from which they are separated by Camaderry Mountain. In 1859 the Glendasan and Glendalough mines were connected with each other by a series of adits, now flooded, through the mountain. This made it easier to transport ore from Glendalough and process it there.

Wildlife

Glendalough is a good place to look for some of Ireland's newest breeding species, such as the goosander and great spotted woodpecker, and some of the rarest, such as the redstart and wood warbler; peregrine, dipper, cuckoo, jay and buzzard can also be seen.[6]

Recreation

.jpg)

There are many walking trails of varying difficulty around Glendalough. Within the valley itself there are nine colour-coded walking trails maintained by Wicklow Mountains National Park. They all begin at an information office located near the Upper Lough where maps are available to purchase. There are also a number of guided walk options.

The Wicklow Way, a long distance waymarked walking trail, passes through Glendalough on its way from Rathfarnham in the north to its southerly point of Clonegal in County Carlow.

Rock climbing Glendalough's granite cliffs, situated on the hillside above the north-western end of the valley, have been a popular rock-climbing location since the first climbs were established in 1948. The current guidebook, published in 1993, lists about 110 routes, at all grades up to E5/6a, though several more climbs, mainly in the high grades, have been recorded since then.[7]

The climbs vary between one and four pitches, and up to over 100m in length. There are several sectors:

- Twin Buttress, a large buttress divided in the middle by a seasonal waterfall, which contains the most popular climbs. This area is approached via the zig-zag path at the head of the valley.

- The Upper Cliffs, a band of cliffs high up on the hillside east of Twin Buttress.

- Acorn Buttress, a small buttress just below Twin Buttress, which is a popular base-camp location.

- Hobnail Buttress, a small buttress with some easy climbing, on the hillside one kilometre to the east.

The quality of the climbing along with the variety of grades attracts climbers of all standards to Glendalough, and makes it a favourite destination for Dublin climbers in particular. The Irish Mountaineering Club has operated a climbing hut in the area since the 1950s. Below the crag is an extensive boulder field. This is a popular location for bouldering activities,[8] the boulders within easy reach of the path being especially popular.

Gallery

Saint Kevin's Church, Glendalough, Co. Wicklow, Ireland 2012

Saint Kevin's Church, Glendalough, Co. Wicklow, Ireland 2012 Lower Lake.

Lower Lake.- Upper Lake.

Round tower.

Round tower. St. Kevin's Church

St. Kevin's Church 1949 one shilling Irish stamp with Vox Hiberniae flying over Gleann Dá Loċ.

1949 one shilling Irish stamp with Vox Hiberniae flying over Gleann Dá Loċ. Upper lake and valley

Upper lake and valley The Round Tower at Glendalough.

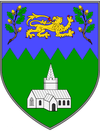

The Round Tower at Glendalough. St. Kevin's Church on the coat of arms of County Wicklow

St. Kevin's Church on the coat of arms of County Wicklow Glendalough (1890s)

Glendalough (1890s) Glendalough Gatehouse

Glendalough Gatehouse St Kevin, Glendalough

St Kevin, Glendalough- St Kevins Bed

Glendalough(2011)

Glendalough(2011)

See also

- Abbot of Glendalough

- Bishop of Glendalough

- Irish round tower

- Saint Kevin

- List of abbeys and priories in County Wicklow

References

- ↑ Glendalough

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Glendalough Visitors Guide, Produced by "The Office of Public Works" (Oifig na nOibreacha Poibli), Glendalough, County Wicklow.

- ↑ "Havhingsten fra Glendalough (Skuldelev 2) transl. The Sea Stallion from Glendaloug". Retrieved 14 December 2011.

- 1 2 Catholic Hierarchy List of Titular Bishops of Glenndálocha

- ↑ Nairn, Richard (2001). Discovering Wild Wicklow. TownHouse and CountryHouse. p. 8. ISBN 1-86059-141-8.

- ↑ BirdWatch Ireland Irish Birds Vol.7 (2004-5) pp.377,542,547; Vol.8 (2006-9) pp. 101,103,253,257,367,369,574,576; Vol.9 (2010) p.69

- ↑ Lyons, Joe; Fenlon, Robbie (1993). Rock Climbing Guide to Wicklow. Mountaineering Council of Ireland. ISBN 978-0-902940-11-6.

- ↑ TheShortSpan - Bouldering in Ireland

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Glendalough. |

Glendalough travel guide from Wikivoyage

Glendalough travel guide from Wikivoyage- List of the various monuments in Glendalough

- Megalithic Ireland's Glendalough Monastic Site

- Monastic buildings of Glendalough (Archived link)

Coordinates: 53°00′37″N 6°19′39″W / 53.01028°N 6.32750°W