Gjirokastër

| Gjirokastër | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Municipality | ||||||||

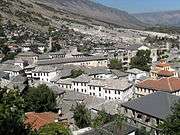

Gjirokastër photomontage Clockwise, from top: Gjirokastra from the Castle, Street in Gjirokastër, Clock Tower of Castle, Castle Wall, Ottoman House, Gjirokastër Castle Walls | ||||||||

Gjirokastër | ||||||||

| Coordinates: 40°04′N 20°08′E / 40.067°N 20.133°ECoordinates: 40°04′N 20°08′E / 40.067°N 20.133°E | ||||||||

| Country |

| |||||||

| County | Gjirokastër | |||||||

| Government | ||||||||

| • Mayor | Zamira Rami (SMI) | |||||||

| Area | ||||||||

| • Municipality | 469.25 km2 (181.18 sq mi) | |||||||

| • Administrative Unit | 5.25 km2 (2.03 sq mi) | |||||||

| Elevation | 300 m (1,000 ft) | |||||||

| Population (2011) | ||||||||

| • Municipality | 25,301 | |||||||

| • Municipality density | 54/km2 (140/sq mi) | |||||||

| • Administrative Unit | 19,836 | |||||||

| • Administrative Unit density | 3,800/km2 (9,800/sq mi) | |||||||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | |||||||

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | |||||||

| Postal Code | 6001–6003 | |||||||

| Area Code | (0)84 | |||||||

| Vehicle registration | AL | |||||||

| Historic Centres of Berat and Gjirokastra | |

|---|---|

| Name as inscribed on the World Heritage List | |

| |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iii, iv |

| Reference | 569 |

| UNESCO region | Europe |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2005 (29th Session) |

| Extensions | 2008 |

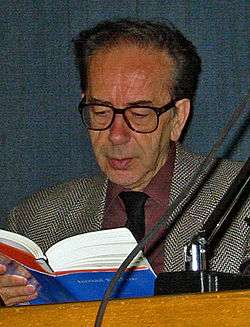

Gjirokastër is a town and a municipality in southern Albania. Lying in the historical region of Epirus, it is the capital of Gjirokastër County. Its old town is a World Heritage Site described as "a rare example of a well-preserved Ottoman town, built by farmers of large estate." Gjirokastër is situated in a valley between the Gjerë mountains and the Drino, at 300 metres above sea level. The city is overlooked by Gjirokastër Fortress, where the Gjirokastër National Folklore Festival is held every five years. Gjirokastër is the birthplace of former Albanian communist leader Enver Hoxha and notable writer Ismail Kadare. It hosts the Eqrem Çabej University.

The present municipality was formed at the 2015 local government reform by the merger of the former municipalities of Antigonë, Cepo, Gjirokastër, Lazarat, Lunxhëri, Odrie and Picar, that became municipal units. The seat of the municipality is the town Gjirokastër.[1] The total population is 25,301 (2011 census), in a total area of 469.25 square kilometres (181.18 sq mi).[2] The population of the former municipality at the 2011 census was 19,836.[3]

The city appears in the historical record in 1336 by its Greek name, Argyrokastro (Αργυρόκαστρο, often written Argyrocastro or Argyro-Castro),[4] as part of the Byzantine Empire.[5] It became part of the Orthodox Christian doecese of Dryinoupolis and Argyrokastro after the destruction of nearby Adrianoupolis.[6] Gjirokastër later became the center of the principality ruled by John Zenevisi (1373-1417) before falling under Ottoman rule for the next five centuries.[5] Throughout the Ottoman era Gjirokastër was officially known in Ottoman Turkish as Ergiri and also Ergiri Kasrı.[7] During the Ottoman period conversions to Islam and an influx of Muslim converts from the surrounding countryside made Gjirokastër go from being an overwhelmingly Christian city in the 16th century into one with a large Muslim population by the early 19th century.[8][9] Gjirokastër also became a major religious centre for Bektashi Sufism.[10] Taken by the Hellenic Army during the Balkan Wars of 1912-3 on account of its large Greek population,[11] it was eventually incorporated into the newly independent state of Albania in 1913. This proved highly unpopular with the local Greek population, who rebelled; after several months of guerrilla warfare, the short-lived Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus was established in 1914 with Gjirokastër as its capital. It was definitively awarded to Albania in 1921.[12] In more recent years, the city witnessed anti-government protests that lead to the Albanian civil war of 1997.[13]

Alongside Muslim and Orthodox Albanians who form the majority population, the city is also home to a substantial Greek minority.[14][15] Gjirokastër, together with Sarandë, is considered one of the centers of the Greek community in Albania,[16] and there is a consulate of Greece.[17]

Etymology

The city appeared for the first time in historical records under its medieval Greek name of Argyrocastron (Greek: Αργυρόκαστρον), as mentioned by John VI Kantakouzenos in 1336.[18] The name comes from the Medieval Greek ἀργυρόν (argyron), meaning "silver", and κάστρον (kastron), from the Latin castrum meaning "castle" or "fortress", thus "silver castle". Byzantine chronicles also used the similar name Argyropolyhni, meaning silvertown (Greek: Αργυροπολύχνη).[19] The theory that the city took the name of the Princess Argjiro, a legendary figure about whom 19th century author Kostas Krystallis wrote a short novel[20] and Ismail Kadare wrote a poem in the 1960s. It is considered a folk etymology, since the princess is said to have lived later, in the 15th century.[21]

The definite Albanian form of the name of city is Gjirokastra, while in the Gheg Albanian dialect it is known as Gjinokastër, both of which derive from the Greek name.[22] Alternative spellings found in Western sources are Girokaster and Girokastra. In Aromanian the city is known as Ljurocastru, while in modern Greek it is known Αργυρόκαστρο (Argyrokastro). During the Ottoman era the town was known in Turkish as Ergiri.[7]

History

Archaeological evidence points out that during the Bronze Age the region was inhabited by populations that probably spoke a northwestern Greek dialect.[23] Archaeologists have found pottery objects of the early Iron Age in Gjirokastër, which first appeared in the late Bronze Age in Pazhok, Elbasan District, and are found throughout Albania.[24] The earliest recorded inhabitants of the area around Gjirokastër were the Greek tribe of the Chaonians.

The city's walls date from the third century. The high stone walls of the Citadel were built from the sixth to the twelfth century.[25] During this period, Gjirokastër developed into a major commercial center known as Argyropolis (Ancient Greek: Ἀργυρόπολις, meaning "Silver City") or Argyrokastron (Ancient Greek: Ἀργυρόκαστρον, meaning "Silver Castle").[26]

The city was part of the Despotate of Epirus and was first mentioned by the name Argyrokastro by John VI Kantakouzenos in 1336.[4] The first mention of Albanian nomadic groups occurred in the early 14th century, where they were searching for new pasture lands and ravaging settlements in the region.[19] These Albanians had entered the region and took advantage of the situation after the Black death had decimated the local Epirote population.[19] During 1386–1418 it became the capital of the Principality of Gjirokastër of John Zenevisi. In 1417 it became part of the Ottoman Empire and in 1419 it became the county town of the Sanjak of Albania.[27] During the Albanian Revolt of 1432–36 it was besieged by forces under Thopia Zenevisi, but the rebels were defeated by Ottoman troops led by Turahan Bey[28] In 1570s local nobles Manthos Papagiannis and Panos Kestolikos, discussed as Greek representative of enslaved Greece and Albania with the head of the Holy League, John of Austria and various other European rulers, the possibility of an anti-Ottoman armed struggle, but this initiative was fruitless.[29][30][31]

According to Turkish traveller Evliya Çelebi, who visited the city in 1670, at that time there were 200 houses within the castle, 200 in the Christian eastern neighborhood of Kyçyk Varosh (meaning small neighborhood outside the castle), 150 houses in the Byjyk Varosh (meaning big neighborhood outside the castle), and six additional neighborhoods: Palorto, Vutosh, Dunavat, Manalat, Haxhi Bey, and Memi Bey, extending on eight hills around the castle.[32] According to the traveller, the city had at that time around 2000 houses, eight mosques, three churches, 280 shops, five fountains, and five inns.[32] From the 16th century until the early 19th century Gjirokastër went from being a predominantly Christian city to one with a Muslim majority due to much of the urban population converting to Islam alongside an influx of Muslim converts from the surrounding countryside.[8][9]

In 1811, Gjirokastër became part of the Pashalik of Yanina, then led by the Albanian-born Ali Pasha of Ioannina and was transformed into a semi-autonomous fiefdom in the southwestern Balkans until his death in 1822. After the fall of the pashalik in 1868, the city was the capital of the sanjak of Ergiri. On 23 July 1880, southern Albanian committees of the League of Prizren held a congress in the city, in which was decided that if Albanian-populated areas of the Ottoman Empire were ceded to neighbouring countries, they would revolt.[33] During the Albanian National Awakening (1831–1912), the city was a major centre of the movement, and some groups in the city were reported to carry portraits of Skanderbeg, the national hero of the Albanians during this period.[34] Gjirokastër from the middle of the nineteenth century also prominently contributed to the wider Ottoman Empire through individuals that served as Kadıs (civil servants) and was an important centre of Islamic culture.[7] The Albanian population of Gjirokastër during the late 19th century was split between two groups: the urban liberals who wanted to cooperate with the Greeks and Albanian nationalists who formed guerilla bands operating in the countryside.[9] During the 19th and early 20th century, Albanian speaking Muslims were the majority population of Gjirokastër, while only a few Greek-speaking families lived there.[9]

Given its large Greek population, the city was claimed and taken by Greece during the First Balkan War of 1912–1913, following the retreat of the Ottomans from the region.[35] However, it was awarded to Albania under the terms of the Treaty of London of 1913 and the Protocol of Florence of 17 December 1913.[36]

This turn of events proved highly unpopular with the local Greek population, and their representatives under Georgios Christakis-Zografos formed the Panepirotic Assembly in Gjirokastër in protest.[37] The Assembly, short of incorporation with Greece, demanded either local autonomy or an international occupation by forces of the Great Powers for the districts of Gjirokastër, Sarandë, and Korçë.[38]

In March 1914, the Northern Epirote Declaration of Independence was announced in Gjirokastër and it was confirmed in the Protocol of Corfu.[39] The Republic, however, was short-lived, as Albania collapsed at the beginning of World War I.[40] The Greek military returned in October–November 1914, and again captured Gjirokastër, along with Saranda and Korçë.[41] In April 1916, the territory referred to by Greeks as Northern Epirus, including Gjirokastër, was annexed to Greece.[41] The Paris Peace Conference, 1919 restored the pre-war status quo, essentially upholding the border line decided in the 1913 Protocol of Florence, and the city was again returned to Albanian control.[42]

In April 1939, Gjirokastër was occupied by Italy following the Italian invasion of Albania. In December 8, 1940, during the Greco-Italian War, the Hellenic Army entered the city and stayed for a five-month period before capitulating to Nazi Germany in April 1941 and returning the city to Italian command. After the capitulation of Italy in the Armistice of Cassibile in September 1943, the city was taken by German forces and eventually returned to Albanian control in 1944.

The postwar communist regime developed the city as an industrial and commercial centre. It was elevated to the status of a museum town,[43] as it was the birthplace of the leader of the People's Socialist Republic of Albania, Enver Hoxha, who had been born there in 1908. His house was converted into a museum.[44]

The demolition of the monumental statue of the authoritarian leader Enver Hohxa in Gjirokastër by members of the local Greek community in August 1991 marked the end of the one-party state.[45] Gjirokastër suffered severe economic problems following the end of communist rule in 1991. In the spring of 1993, the region of Gjirokastër became a center of open conflict between Greek minority members and the Albanian police.[46] The city was particularly affected by the 1997 collapse of a massive pyramid scheme which destabilised the entire Albanian economy.[13] The city became the focus of a rebellion against the government of Sali Berisha; violent anti-government protests took place which eventually forced Berisha's resignation. On 16 December 1997, Hoxha's house was damaged by unknown attackers, but subsequently restored.[47]

Religion and culture

The region was part of the Eastern Orthodox diocese of Dryinoupolis, part of the metropolitan bishopric of Ioannina. It was first mentioned in a notitia of the 10th-11th century. With the destruction of nearby Adrianupolis its see was transferred to Gjirokastër and assumed the name Doecese of Dryinopoulis and Argyrokastron (Greek: Δρυϊνουπόλεως και Αργυροκάστρου). In 1835 it was promoted to metropolitan bishopric under the direct jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople.[6] Today, the city is home to a diocese part of the Orthodox Autocephalous Church of Albania.[48] The two existing churches of the city were re-built at the end of the 18th century, after approval by the local Ottoman authorities who received large bribes by the Orthodox community. The Orthodox Cathedral of the "Transfiguration of the Saviour" was rebuilt at 1773 on the site of an older church and is located at the castle quarters.[49]

During the Ottoman period Gjirokastër was a significant centre for the Muslim Sufi Bektashi Order, especially in relation to its spread and literary activity.[10] In 1925, Albania became the world center of the Bektashi Order, a Muslim sect. The sect was headquartered in Tirana, and Gjirokastër was one of six districts of the Bektashi Order in Albania, with its center at the tekke of Baba Rexheb.[50] The city retains a large Bektashi and Sunni population. Historically there were 15 and tekkes and mosques, of which 13 were functional in 1945.[51] Only Gjirokastër Mosque has survived; the remaining 12 were destroyed or closed during the Cultural Revolution of the communist government in 1967.[51]

17th-century Ottoman traveller Evliya Çelebi, who visited the city in 1670, described the city in detail. One Sunday, Çelebi heard the sound of a vajtim, the traditional Albanian lament for the dead, performed by a professional mourner. The traveller found the city so noisy that he dubbed Gjirokastër the "city of wailing".[52]

The novel Chronicle in Stone by Albanian writer Ismail Kadare tells the history of this city during the Italian and Greek occupation in World War I and II, and expands on the customs of the people of Gjirokastër. At the age of twenty-four, Albanian writer Musine Kokalari wrote an 80-page collection of ten youthful prose tales in her native Gjirokastrian dialect: As my old mother tells me (Albanian: Siç me thotë nënua plakë), Tirana, 1941. The book tells the day-by-day struggles of women of Gjirokastër, and describes the prevailing mores of the region.[53]

Gjirokastër, home to both Albanian and Greek polyphonic singing, is also home to the National Folklore Festival (Albanian: Festivali Folklorik Kombëtar) that is held every five years. The festival started in 1968[54] and was most recently held in 2009, its ninth season.[55] The festival takes place on the premises of Gjirokastër Fortress. Gjirokastër is also where the Greek language newspaper Laiko Vima is published. Founded in 1945, it was the only Greek-language printed media allowed during the People's Socialist Republic of Albania.[56]

Landmarks

The city is built on the slope surrounding the citadel, located on a dominating plateau.[43] Although the city's walls were built in the third century and the city itself was first mentioned in the 12th century, the majority of the existing buildings date from 17th and 18th centuries. Typical houses consist of a tall stone block structure which can be up to five stories high. There are external and internal staircases that surround the house. It is thought that such design stems from fortified country houses typical in southern Albania. The lower storey of the building contains a cistern and the stable. The upper storey is composed of a guest room and a family room containing a fireplace. Further upper stories are to accommodate extended families and are connected by internal stairs.[43] Since Gjirokastër's membership to UNESCO, a number of houses have been restored, though others continue to degrade.

Many houses in Gjirokastër have a distinctive local style that has earned the city the nickname "City of Stone", because most of the old houses have roofs covered with flat dressed stones. A very similar style can be seen in the Pelion district of Greece. The city, along with Berat, was among the few Albanian cities preserved in the 1960s and 1970s from modernizing building programs. Both cities gained the status of "museum town" and are UNESCO World Heritage sites.[43]

Gjirokastër Fortress dominates the town and overlooks the strategically important route along the river valley. It is open to visitors and contains a military museum featuring captured artillery and memorabilia of the Communist resistance against German occupation, as well as a captured United States Air Force plane, to commemorate the Communist regime's struggle against the imperialist powers. Additions were built during the 19th and 20th centuries by Ali Pasha of Ioannina and the government of King Zog I of Albania. Today it possesses five towers and houses a clock tower, a church, water fountains, horse stables, and many more amenities. The northern part of the castle was turned into a prison by Zog's government and housed political prisoners during the communist regime.

Gjirokastër features an old Ottoman bazaar which was originally built in the 17th century; it was rebuilt in the 19th century after a fire. There are more than 500 homes preserved as "cultural monuments" in Gjirokastër today. The Gjirokastër Mosque, built in 1757, dominates the bazaar.[51]

When the town was first proposed for inclusion on the World Heritage list in 1988, International Council on Monuments and Sites experts were nonplussed by a number of modern constructions which detracted from the old town's appearance. The historic core of Gjirokastër was finally inscribed in 2005, 15 years after its original nomination.

Climate

Gjirokastër is situated between the lowlands of western Albania and the highlands of the interior, and has thus a hot-summer Mediterranean climate, though, (as is normal for Albania), much heavier rainfall than usual for this climate type.

| Climate data for Gjirokastër | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 9 (48) |

11 (52) |

13 (55) |

18 (64) |

23 (73) |

28 (82) |

32 (90) |

34 (93) |

27 (81) |

23 (73) |

15 (59) |

11 (52) |

20.3 (68.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5 (41) |

6 (43) |

7 (45) |

12 (54) |

16 (61) |

20 (68) |

23 (73) |

24 (75) |

19 (66) |

14 (57) |

10 (50) |

6 (43) |

13.5 (56.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 1 (34) |

1 (34) |

2 (36) |

6 (43) |

10 (50) |

13 (55) |

15 (59) |

15 (59) |

12 (54) |

8 (46) |

5 (41) |

2 (36) |

7.5 (45.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 290 (11.42) |

230 (9.06) |

190 (7.48) |

90 (3.54) |

50 (1.97) |

40 (1.57) |

10 (0.39) |

10 (0.39) |

60 (2.36) |

180 (7.09) |

400 (15.75) |

320 (12.6) |

1,870 (73.62) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 11 | 10 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 14 | 12 | 81 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 71 | 69 | 68 | 69 | 70 | 62 | 57 | 57 | 64 | 67 | 75 | 73 | 66.8 |

| Source #1: Weatherbase | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Climate data | |||||||||||||

Economy

Gjirokastër is principally a commercial center with some industries, notably the production of foodstuffs, leather, and textiles.[57] Recently a regional agricultural market that trades locally produced groceries has been built in the city.[58] Given the potential of southern Albania to supply organically-grown products, and its relationship with Greek counterparts of the nearby city of Ioannina, it is likely that the market will dedicate itself to organic farming in the future. However, currently trademarking and marketing of such products are far from European standards.[58] The Chamber of Commerce of the city, created in 1988, promotes trade with the Greek border areas.[59] As part of the financial support from Greece to Albania, the Hellenic Armed Forces built a hospital in the city.[60]

In recent years, many traditional houses are being reconstructed and owners lured to come back, thus revitalizing tourism as a potential revenue source for the local economy.[61][62][63][64] However, some houses continue to degrade from lack of investment, abandonment or inappropriate renovations as local craftsmen are not part of these projects.[65] In 2010, following the Greek economic crisis, the city was one of the first areas in Albania to suffer, since many Albanian emigrants in Greece are becoming unemployed and thus are returning home.[66]

Education

The first school in the city, a Greek language school, was erected in the city in 1663. It was sponsored by local merchants and functioned under the supervision of the local bishop. In 1821, when the Greek War of Independence broke out, it was destroyed, but it was reopened in 1830.[67][68] In 1727 a madrasa started to function in the city, and it worked uninterruptedly for 240 years until 1967, when it was closed due to the Cultural Revolution applied in communist Albania.[51] In 1861–1862 a Greek language school for girls was founded, financially supported by the local Greek benefactor Christakis Zografos.[69] The first Albanian school in Gjirokastër was opened in 1886.[70] Today Gjirokastër has seven grammar schools, two general high schools (of which one is the Gjirokastër Gymnasium), and two professional ones.

The city is home to the Eqrem Çabej University, which opened its doors in 1968. The university has recently been experiencing low enrollments, and as a result the departments of Physics, Mathematics, Biochemistry, and Kindergarten Education did not function during the 2008–2009 academic year.[71] In 2006, the establishment of a second university in Gjirokastër, a Greek-language one, was agreed upon after discussions between the Albanian and Greek governments.[72] The program had an attendance of 35 students as of 2010, but was abruptly suspended when the University of Ioannina in Greece refused to provide teachers for the 2010 school year and the Greek government and the Latsis foundation withdrew funding.[71]

Sports

Football (soccer) is popular in Gjirokastër: the city hosts Luftëtari Gjirokastër, a club founded in 1929. The club has competed in international tournaments and played in the Albanian Superliga until 2006–2007. Currently the team plays in the Albanian First Division. The soccer matches are played in Gjirokastër Stadium, which can hold up to 8,500 spectators.[73]

Demographics

The town has 43,000 inhabitants.[74] Gjirokastër is home to an ethnic Greek community that according to one source numbered about 4000 in 1989,[75] although Greek spokesmen have claimed that up to 34% of the town is Greek.[76] Gjirokastër is considered the center of the Greek community in Albania.[11] Given the large Greek population in the town and surrounding area, there is a Greek consulate in the town.[77] In fieldwork undertaken by Greek scholar Leonidas Kallivretakis in the area during 1992, the district of Gjirokastër had 66.000 inhabitants of which 40% were Greeks, 12% Vlachs and an Orthodox Albanian population of 21%.[14] These communities are Orthodox and collectively made up 63% of the district's Christian population.[14] While 28% were Muslim Albanians.[14] Overall the Greek community was the most numerous ethno-religious group (40%), while Albanians, irrespective of religious background, in 1992 were a plurality and collectively consisted 49% of the district's total population.[14] Within Gjirokastër district, Greeks populate all the settlements of both former municipalities of Dropull i Sipërm and Dropull i Poshtëm and also all settlements of Pogon municipality (except the village of Selckë).[14][78][79] Gjirokastër has a mixed population consisting of Muslim Albanians, Greeks and an Orthodox Albanian population while the city in 1992 had an overall Albanian majority.[14]

Transport

Gjirokastër is served by the SH4 Highway, which connects it to Tepelenë in the north and the Dropull region and Greek border 30 km (19 mi) to the south.

International relations

Twin towns – Sister cities

Gjirokastër is twinned with:

Notable people

- Ali Alizoti, politician in late 19th century

- Fejzi Alizoti, interim Prime Minister of Albania in 1914

- Kyriakoulis Argyrokastritis (−1828), revolutionary of the Greek War of Independence

- Arjan Bellaj, retired soccer player and member of the Albania national football team

- Elmaz Boçe, signatory of the Albanian Declaration of Independence and politician

- Bledar Devolli, footballer

- Vanghel Dule, representative of the Greek minority in Albanian politics.

- Rauf Fico, politician

- Bashkim Fino, politician and former Prime Minister of Albania

- Georgios Dimitriou, 18th century author

- Ioannis Doukas 19th century painter

- Ramize Gjebrea World war II notable partisan

- Christos Gikas, athlete in Greco-Roman wrestilng

- Gregory IV of Athens, scholar and Archbishop of Athens

- Altin Haxhi, international soccer player; capped in the Albania national team

- Fatmir Haxhiu, painter

- Veli Harxhi, signatory of the Albanian Declaration of Independence and politician

- Enver Hoxha, former first Secretary of the Albanian Party of Labor, and leader of socialist Albania

- Feim Ibrahimi, composer

- Ismail Kadare, novelist, winner of the Man Booker International Prize in 2005 and Prince of Asturias Award in 2009

- Mehmed Kalakula, politician

- Xhanfize Keko movie director

- Saim Kokona, cinematographer

- Albi Kondi, football player

- Eqrem Libohova, former Prime Minister of Albania

- Sabit Lulo, politician

- Bule Naipi, World War II People's Heroine of Albania

- Omer Nishani, Head of State of Albania from 1944–1953

- Arlind Nora, footballer

- Bahri Omari, politician

- Jani Papadhopulli, signatory of the Albanian Declaration of Independence and politician

- Manthos Papagiannis, 16th century revolutionary

- Xhevdet Picari, commander in the Vlora War

- Pertef Pogoni, 20th century politician

- Baba Rexheb, Bektashi Sufi religious leader and saint

- Mehmet Tahsini, politician and professor

- Çerçiz Topulli, 20th-century nationalist and guerrilla fighter

- Bajo Topulli, brother of Çerçiz, nationalist and guerrilla fighter

- Takis Tsiakos, Greek poet

- Alexandros Vasileiou, merchant and Greek scholar

- Michael Vasileiou, merchant; brother of Alexandros

- Mahmud Xhelaledini, politician

- Arjan Xhumba, retired soccer player and member of the Albania national football team

Gallery

|

See also

- Gjirokastër National Folklore Festival

- Tourism in Albania

- History of Albania

- Music of Albania

- Lord Byron

- Antigonia

- Hadrianopolis

- Greeks in Albania

References

- ↑ Law nr. 115/2014

- ↑ Interactive map administrative territorial reform

- ↑ 2011 census results

- 1 2 Kiel, Machiel. Ottoman Architecture in Albania, 1385–1912. Beşiktaş, Istanbul: Research Centre for Islamic History, Art and Culture. p. 138. ISBN 978-92-9063-330-3. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- 1 2 Ward 1983, p. 70.

- 1 2 Giakoumis, Konstantinos (2010). "The Orthodox Church in Albania Under the Ottoman Rule 15th-19th Century". In Schmitt, Oliver Jens & Andreas Rathberger (eds). Religion und Kultur im albanischsprachigen Südosteuropa [Religion and culture in Albanian-speaking southeastern Europe]]. Peter Lang. pp. 80.

- 1 2 3 Ali, Çaksu (2006). Proceedings of the Second International Symposium on Islamic Civilisation in the Balkans, Tirana, Albania, 4-7 December 2003. Research Center for Islamic History, Art and Culture. p. 115. "At least since the middle of the nineteenth century; families or individuals from Gjirokastër (the Ottoman Ergiri or Ergiri Kasrı) in Southern Albania, and from Libohova, a small town located twenty kilometers from Gjirokastër, gave a huge number of Kadıs, who were in charge in the whole Ottoman Empire, making of these two localities important centres of Islamic culture."

- 1 2 Giakoumis, Konstantinos (2010). "The Orthodox Church in Albania Under the Ottoman Rule 15th-19th Century". In Schmitt, Oliver Jens & Andreas Rathberger (eds). Religion und Kultur im albanischsprachigen Südosteuropa [Religion and culture in Albanian-speaking southeastern Europe]]. Peter Lang. pp. 86-87.

- 1 2 3 4 Kokolakis, Mihalis (2003). Το ύστερο Γιαννιώτικο Πασαλίκι: χώρος, διοίκηση και πληθυσμός στην τουρκοκρατούμενη Ηπειρο (1820-1913) [The late Pashalik of Ioannina: Space, administration and population in Ottoman ruled Epirus (1820-1913). EIE-ΚΝΕ. p.52. "β. Ο διεσπαρμένος ελληνόφωνος πληθυσμός περιλάμβανε... και μικρό αριθμό οικογενειών στα αστικά κέντρα του Αργυροκάστρου και της Αυλώνας. [b. The scattered Greek-speaking population included ... and a small number of families in the cities of Gjirokastra and Vlora.]"; p. 54. "Η μουσουλμανική κοινότητα της Ηπείρου, με εξαίρεση τους μικρούς αστικούς πληθυσμούς των νότιων ελληνόφωνων περιοχών, τους οποίους προαναφέραμε, και τις δύο με τρεις χιλιάδες διεσπαρμένους «Τουρκόγυφτους», απαρτιζόταν ολοκληρωτικά από αλβανόφωνους, και στα τέλη της Τουρκοκρατίας κάλυπτε τα 3/4 περίπου του πληθυσμού των αλβανόφωνων περιοχών και περισσότερο από το 40% του συνόλου. [The Muslim community in Epirus, with the exception of small urban populations of the southern Greek-speaking areas, which we mentioned, and 2-3000 dispersed "Muslim Romani", consisted entirely of Albanian speakers, and in the late Ottoman period covered approximately 3/4 of population ethnic Albanian speaking areas and more than 40% of the total area."; pp.55-56. "Σ' αυτά τα μέρη οι μουσουλμανικές κοινότητες, όταν υπήρχαν, περιορίζονταν στο συμπαγή πληθυσμό ορισμένων πόλεων και κωμοπόλεων (Αργυρόκαστρο, Λιμπόχοβο, Λεσκοβίκι, Δέλβινο, Παραμυθιά). [In these parts of the Muslim communities, where present, were limited to compact population of certain towns and cities (Gjirokastra, Libohovë, Leskovik, Delvino, Paramythia)." p. 91. Στο Αργυρόκαστρο οι Αλβανιστές διασπάστηκαν ανάμεσα στους φιλελεύθερους της πόλης, που ζητούσαν τη συνεργασία με τους Έλληνες, και στα ακραία εθνικιστικά στοιχεία, που σχημάτισαν στην ύπαιθρο ανταρτικές ομάδες. [The Albanians of Gjirokastër were split between the liberals of the city, calling for cooperation with the Greeks, and the extreme nationalist elements, which formed in the countryside as guerrilla groups.]"; pp. 370, 374.

- 1 2 Norris, Harry Thirlwall (1993). Islam in the Balkans: religion and society between Europe and the Arab world. University of South Carolina Press. p. 134. "The southern Albanian town of Gjirokastër was also for centuries and important centre for Baktāshī propagation and literary activity."

- 1 2 James Pettifer. "The Greek Minority in Albania in the Aftermath of Communism" (PDF). Camberley, Surrey: Conflict Studies Research Centre, Royal Military Academy Sandhurst. p. 6. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

Given its large Greek population, the city of Gjirokaster was a particularly large center of irredentist ambition

- ↑ Miller, William (1966). The Ottoman Empire and Its Successors, 1801-1927. Routledge. pp. 543–544. ISBN 978-0-7146-1974-3.

- 1 2 Jeffries, Ian (2002). Eastern Europe at the turn of the twenty-first century: a guide to the economies in transition. Routledge. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-415-23671-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kallivretakis, Leonidas (1995). "Η ελληνική κοινότητα της Αλβανίας υπό το πρίσμα της ιστορικής γεωγραφίας και δημογραφίας [The Greek Community of Albania in terms of historical geography and demography." In Nikolakopoulos, Ilias, Kouloubis Theodoros A. & Thanos M. Veremis (eds). Ο Ελληνισμός της Αλβανίας [The Greeks of Albania]. University of Athens. p. 34. "Στα πλαίσια της επιτόπιας έρευνας που πραγματοποιήσαμε στην Αλβανία (Νοέμβριος-Δεκέμβριος 1992), μελετήσαμε το ζήτημα των εθνοπολιτισμικών ομάδων, όπως αυτές συνειδητοποιούνται σήμερα επί τόπου. [As part of the fieldwork we held in Albania (November–December 1992), we studied the issue of ethnocultural groups, as they are realized today on the spot.]"; p. 42. "Στο Νομό του Αργυροκάστρου: Έλληνες 40%, Βλάχοι 12%, Αλβανοί Χριστιανοί 21%, Αλβανοί Μουσουλμάνοι 28%, επί συνόλου 66.000 κατοίκων, 63% Χριστιανοί, 49% Αλβανοί." p. 43. "4) Ακόμη και εκεί που η ύπαιθρος είναι ελληνική ή ελληνίζουσα, οι πόλεις διαθέτουν αλβανική πλειοψηφία. Αυτό φαίνεται καθαρά στις περιπτώσεις Αργυροκάστρου και Δελβίνου, όπου οι Νομαρχίες πέρασαν στα χέρια της μειονότητας, όχι όμως και οι Δήμοι των αντιστοίχων πόλεων." "[4) Even where the countryside is Greek or Greekish, cities have an Albanian majority. This is clear where the prefectures of Gjirokastër and Delvinë were passed into the hands of the minority, but not the municipalities of the respective cities.]"; p. 51. "Ε Έλληνες, ΑΧ Αλβανοί Ορθόδοξοι Χριστιανοί, AM Αλβανοί Μουσουλμάνοι, Μ Μικτός πληθυσμός...." p.55. "GJIROKASTRA ΑΡΓΥΡΟΚΑΣΤΡΟ 24216 Μ (ΑΜ + ΑΧ + Ε).”; p.57.

- ↑ Albania: from anarchy to a Balkan identity Authors Miranda Vickers, James Pettifer Edition 2, illustrated, reprint Publisher C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 1997 ISBN 1-85065-290-2, ISBN 978-1-85065-290-8 p. 187

- ↑ James Pettifer. "The Greek Minority in Albania in the Aftermath of Communism" (PDF). Camberley, Surrey: Conflict Studies Research Centre, Royal Military Academy Sandhurst. pp. 11–12. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

The concentration of ethnic Greeks in and around centres of Hellenism such as Saranda and Gjirokastra...

- ↑ The Unit 1996.

- ↑ GCDO History part. "History of Gjirokaster" (in Albanian). Organizata për Ruajtjen dhe Zhvillimin e Gjirokastrës (GCDO). Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- 1 2 3 Giakoumis, Konstantinos (2003), Fourteenth-century Albanian migration and the ‘relative autochthony’ of the Albanians in Epeiros. The case of Gjirokastër." Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies. 27. (1). p. 179: "The Albanians originating... According to the sources, there were two migrant groups, the one which travelled via Ohrid and ended in Thessaly while the other, moving through Kelcyre, reached Gjirokaster and the despotate. The purpose of their occupation was to search for new pasture lands. The combination of fertile plains and mountains rich in grasslands in the region of Gjirokaster was ideal for the poor nomadic Albanians who did not hesitate to ravage cities when they lacked provisions.."; p. 182. "Furthermore, I presented evidence that the in the fourteenth century immigrant Albanians taking advantage of the decimation of the local Epirote population by to the Black death also migrated into the regions of Gjirokastër."

- ↑ Τόμος 170 του Νεοελληνική Γραμματεία. Ηπειρώτικαι αναμνήσεις. Pelekanos Books. ISBN 9789604007691.

- ↑ Sinani, Shaban; Kadare, Ismail; Courtois, Stéphane (2006). Le dossier Kadaré (in French). Paris: O. Jacob. p. 37. ISBN 978-2-7381-1740-3.

- ↑ The New Encyclopaedia Britannica: Micropaedia. Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica. 1993. p. 289. ISBN 0-85229-571-5.

- ↑ Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière (1976). Migrations and Invasions in Greece and Adjacent Areas. Noyes Press. p. 153. ISBN 9780815550471.

The connections of the tumulus-burials at Barc in the southern part of the lakeland were not with the Kukes or Mati tumuli but with those of Vajze and southern Albania; for example, in the long bronze pins, roll-top pins, twin-vessels. handles divided by a cross-bar, and small spectacle-fibulae of an early type. Moreover, the pottery of the 'northwestern geometric style' which was typical of Barc,' was current not in north but in central and south Albania and also in the plain of Ioannina at this time. It is probable that the peoples to the south of the Shkumbi valley and lake Ochrid spoke northwest Greek, being the residue left behind when the migrations carried many of their kindred into the Greek peninsula.

- ↑ Boardman, John (1982-08-05). The Prehistory of the Balkans and the Middle East and the Aegean World, Tenth to Eighth centuries B.C. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-521-22496-3. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- ↑ Wilson, Wesley (1997). Countries & Cultures of the World: The Pacific, Former Soviet Union, & Europe. Chapel Hill, N.C: Professional Press. p. 149. OCLC 1570873038. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ↑ Dvornik, Francis (1958). The Idea of Apostolicity in Byzantium and the Legend of the Apostle Andrew. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 219. OCLC 1196640.

- ↑ Riza, Emin (1992). "Ethnographic and open-air museums" (PDF). UNESCO, Paris. Retrieved March 18, 2011.

- ↑ Imber, Colin (2006). The Crusade of Varna, 1443-45. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 27. ISBN 9780754601449. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ↑ Vakalopoulos, Apostolos Euangelou (1973). History of Macedonia, 1354-1833. Institute for Balkan Studies. p. 195.

The endaevours of two Epirote Greeks, Matthew (or Manthos) Papayiannis and Panos Kestolnikos, are worthy of mention at this point. As "Greek representatives of enslaved Greece and Albania", they came to an understanding with Don John of Austria..

- ↑ Chasiotis, 1965, p. 241: "embajadores griegos de la baja Grecia y Alvania"

- ↑ Cini, Giorgio (1974). Il Mediterraneo Nella Seconda Metà Del '500 Alla Luce Di Lepanto (in Italian). Leo S. Olschki. p. 238.

Delusi rimasero pure i ribelli dell'Epiro del Nord, dove si erano sollevati i notabili greci di Argirocastron Manthos Papagiannis e Panos Kestolicos. Questi notabili si erano accordati con l'arcivescovo di Ochrida Ioachim ed anche con alcuni metropolis della Macedonia occidentale e dell'Epiro, si erano assicurati promesse di Don Juan per un sostegno armato... [Disappointed were also the rebels of Northern Epirus, where they had raised the Greek notables of Argirocastron Manthos Papagiannis and Panos Kestolicos. These chiefs had agreed with the Archbishop of Ochrida Ioachim and also with some metropolitans of western Macedonia and Epirus, and had secured promises of Don Juan for armed support...]

- 1 2 Elsie, Robert (March 2007). "GJIROKASTRA nga udhëpërshkrimi i Evlija Çelebiut" (PDF). Albanica ekskluzive (66): 73–76.

- ↑ Gawrych, George Walter (2006). The Crescent and the Eagle: Ottoman Rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874–1913. London: I.B. Tauris. pp. 23–64. ISBN 978-1-84511-287-5. Retrieved 30 September 2010.

- ↑ Gawrych, George Walter (2006). The Crescent and the Eagle: Ottoman Rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874–1913. London: I.B. Tauris. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-84511-287-5. Retrieved 30 September 2010.

- ↑ James Pettifer. "The Greek Minority in Albania in the Aftermath of Communism" (PDF). Camberley, Surrey: Conflict Studies Research Centre, Royal Military Academy Sandhurst. p. 4. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- ↑ Pentzopoulos, Dimitri (2002). The Balkan Exchange of Minorities and Its Impact on Greece. London: C. Hurst & Co. p. 28. ISBN 1-85065-674-6.

- ↑ Heuberger, Valeria; Suppan, Arnold; Vyslonzil, Elisabeth (1996). Brennpunkt Osteuropa: Minderheiten im Kreuzfeuer des Nationalismus (in German). Vienna: Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag. p. 68. ISBN 978-3-486-56182-1.

- ↑ Ference, Gregory Curtis (1994). Chronology of 20th-Century Eastern European History. Gale Research. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-8103-8879-6.

- ↑ Winnifrith, Tom (2002). Badlands-Borderland: A History of Southern Albania/Northern Epirus. London: Duckworth. p. 130. ISBN 0-7156-3201-9.

- ↑ Bon, Nataša Gregorič (2008). "Formation of the Albanian Nation-State and the Protocol of Corfu (1914)". Contested Spaces and Negotiated Identities in Dhermi/Drimades of Himare/Himara area, Southern Albania (PDF). Nova Gorica. p. 140.

- 1 2 Konidaris, Gerasimos (2005). Schwandner-Sievers, Stephanie, ed. The new Albanian migrations. Sussex Academic Publishing. p. 65. ISBN 9781903900789.

- ↑ Nitsiakos, Vassilis; Mantzos, Constantinos (2003). "Negotiating Culture: Political Uses of Polyphonic Folk Songs in Greece and Albania". In Tziovas, Demetres. Greece and the Balkans: Identities, Perceptions and Cultural Encounters. Aldershot, England: Ashgate Publishing. p. 197. ISBN 0-7546-0998-7.

- 1 2 3 4 Petersen, Andrew (1994). Dictionary of Islamic architecture. Routledge. p. 10. ISBN 0-415-06084-2. Retrieved 2010-06-13.

- ↑ Murati, Violeta. "Tourism with the Dictator". Standard (in Albanian). Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ↑ Pettifer, James; Poulton, Hugh (1994). " The Southern Balkans. London: Minority Rights Group International. p. 29. ISBN 9781897693759.

Under communism the Greek minority was subject to serious human rights abuses, particularly in terms of religious freedom, education in the Greek language and freedom of publication. It played a leading part in the struggle to end the one party state, with the demolition of the monumental statue of Enver Hoxha in Gjirokastra in August 1991 an important landmark

- ↑ Petiffer, James (2001). The Greek Minority in Albania – In the Aftermath of Communism (PDF). Surrey, UK: Conflict Studies Research Centre. p. 13. ISBN 1-903584-35-3.

- ↑ Lajmi (22 March 2010). "Tourism with the Communist Symbols". Gazeta Lajmi (in Albanian). Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ↑ Orthodox Church of Albania. "Building and Restorations" (in Albanian). Retrieved 15 December 2010.

... selitë e Mitropolive të Beratit, Korçës dhe Gjirokastrës...

- ↑ Giakoumis, Konstantinos (2013). "Dialectics of Pragmatism in Ottoman Domestic Interreligious Affairs. Reflections on the Ottoman Legal Framework of Church Confiscation and Construction and a 1741 Firman for Ardenicë Monastery". Balkan Studies. 47: 94, 97, 118. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ↑ Elsie, Robert (2000). A Dictionary of Albanian Religion, Mythology, and Folk Culture. New York: New York University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-8147-2214-5.

- 1 2 3 4 GCDO. "Regjimi komunist në Shqipëri" (in Albanian). Organizata për Ruajtjen dhe Zhvillimin e Gjirokastrës (GCDO). Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ↑ Elsie, Robert (2000). A Dictionary of Albanian Religion, Mythology, and Folk Culture. New York: New York University Press. pp. 95–96. ISBN 0-8147-2214-8. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- ↑ Wilson, Katharina M. (March 1991). An Encyclopedia of Continental Women Writers. 2. New York: Garland. p. 646. ISBN 0-8240-8547-7.

- ↑ Ahmedaja, Ardian; Haid, Gerlinde (2008). European Voices: Multipart Singing in the Balkans and the Mediterranean. 1. Vienna: Böhlau. ISBN 978-3-205-78090-8.

- ↑ Top Channel (25 September 2009). "Gjirokaster, starton Festivali Folklorik Kombetar". Top Channel (in Albanian). Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ Valeria Heuberger; Arnold Suppan; Elisabeth Vyslonzil (1996). Brennpunkt Osteuropa: Minderheiten im Kreuzfeuer des Nationalismus (in German). Vienna: Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag. p. 71. ISBN 978-3-486-56182-1.

- ↑ "Një histori e shkurtër e Gjirokastrës". Gjirokaster.org. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- 1 2 Kote, Odise (16 March 2010). "Tregu rajonal në jug të Shqipërisë dhe prodhimet bio" (in Albanian). Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ↑ Taylor & Francis Group (2004). tes+trade+with+Greek+border+area#v=onepage&q=promotes%20trade%20with%20Greek%20border%20area&f=false Europa World Year, Book 1 Check

|url=value (help). London; New York. ISBN 978-1-85743-254-1. Retrieved 15 December 2010. - ↑ Blitz, ed. by Brad K. (2006). War and change in the Balkans : nationalism, conflict and cooperation. (1. publ. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 230. ISBN 978-0-521-67773-8.

- ↑ "Babameto I Restoration & Revitalization". Cultural Heritage without Borders. Retrieved 2015-06-26.

- ↑ "Babameto II Restoration & Revitalization". Cultural Heritage without Borders. Retrieved 2015-06-26.

- ↑ "Aga Khan Award for Architecture: Conservation of Gjirokastra". Aga Khan Development Network. Retrieved 2011-06-05.

- ↑ "One man's fight to preserve Albania's traditions". BBC. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- ↑ Top Channel Video - Exclusive, Pjesa 1 - 30/09/2012

- ↑ Kote, Odise (2010-03-02). "Kriza greke zbret dhe në Shqipëri" (in Albanian). Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 2010-12-15.

- ↑ Sakellariou, Michaïl V (1997). Epirus: 4000 Years of Greek History and Civilization. Athens: Ekdotike Athenon. p. 308. ISBN 978-960-213-371-2.

- ↑ Ruches,Pyrrhus J (1965). Albania's Captives. Chicago: Argonaut. p. 33.

At a time of almost universal ignorance in Greece, in 1633, it opened the doors of its first Greek school. Sponsored by Argyrocastran merchants in Venice, it was under the supervision of Metropolitan Callistus of Dryinoupolis.

- ↑ Sakellariou, Michaïl V (1997). Epirus: 4000 Years of Greek History and Civilization. Athens: Ekdotike Athenon. p. 308. ISBN 978-960-213-371-2.

- ↑ Victor Roudometof (1996). Nationalism and statecraft in southeastern Europe, 1750-1923. University of Pittsburgh. p. 568.

- 1 2 Μπρεγκάση Αλέξανδρος. "Πάρτε πτυχίο... Αργυροκάστρου". Ηπειρωτικός Αγών. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ↑ "Albania: Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, 2006". U.S. Department of State. 6 March 2007. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- ↑ Worldstadiums. "Stadia in Albania". Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- ↑ Instat of Albania (2009). "Population by towns" (in Albanian). Institute of Statistics of Albania. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ↑ Abrahams, Fred. Human Rights in Post-Communist Albania. Human Rights Watch. p. 119.

About 4,000 Greeks live in Gjirokastër out of a population of 30,000.

- ↑ Bugjazski, Janusz (2002). Political parties of Eastern Europe: a guide to politics in the post-Communist era. M.E. Sharpe. p. 682.

- ↑ Country profile: Bulgaria, Albania. Economist Intelligence Unit, 1996. "Greece has also opened a consulate in the southern town of Gjirokaster, which has a large ethnic Greek population."

- ↑ Dalakoglou, Dimitris (2010). "The road: An ethnography of the Albanian–Greek cross‐border motorway." American Ethnologist. 37. (1): 136. The road section runs parallel to the Drinos River, where most of the Greek-minority villages in Gjirokastër prefecture are located.

- ↑ Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière (1967). Epirus: the Geography, the Ancient Remains, the History and Topography of Epirus and Adjacent Areas. Clarendon Press. p.27. "The present distribution of the Albanian-speaking villages bears little relation to the frontier which was drawn between Greece and Albania after the First World War. In Map 2 I have shown most of the Greek speaking villages in Albanian Epirus and some of the Albanian-speaking villages in Greek Epirus. The map is based on observations made by Clarke and myself during our travels between 1922 and 1939."; p.28-29. In Llunxherië the villages are more compact but smaller, Shtegopul and Saraginishtë, for instance, having only fifty houses each; the people of Llunxherië are all Albanian Orthodox Christians, except those of Erind, who are partly Christian and Mohammedan, and the men, but not the women, know some Greek. Zagorië has the same characteristics, its ten villages extending from Doshnicë to Shepr; the group is endogamous and does not marry with the people of Llunxherië. Pogoni, or Paleo-Pogoni as some people call it, consists of seven Greek-speaking villages near.y 3,000 ft. above sea-level (Poliçan, Skorë, Hlomo, Sopik, Mavrojer, Çatistë, and, on the Greek side of the frontier, Drimadhes), the biggest, Poliçan, has a population of 2,500 persons and Sopik has 300 houses. The Pogoniates normally marry only within their group, but occasionally a bride may be taken from Zagorië and then she is taught Greek."

Sources

- "Gjirokastër". Encyclopædia Britannica, 2006

- "Gjirokastër or Gjinokastër". The Columbia Encyclopedia, 2004

- The Unit (1996). Country Profile: Bulgaria, Albania. The Unit.

- Ward, Philip (1983). Albania: a travel guide. Oleander Press. ISBN 978-0-906672-41-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gjirokastër. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Gjirokastër. |

- Office for Administration and Coordination of Museum City of Gjirokastër

- Adventures in Preservation in Gjirokastër

- Photo Gallery of Gjirokastër from Hotel Kalemi

- Photo Gallery of Gjirokastër, 2015 year

- Municipality of Gjirokastër Website