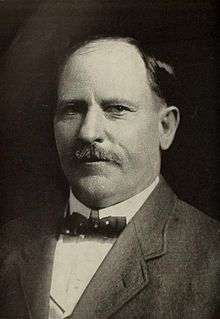

George Washington Donaghey

| George Washington Donahey | |

|---|---|

| |

| 22nd Governor of Arkansas | |

|

In office January 14, 1909 – January 16, 1913 | |

| Preceded by |

Jesse M. Martin as Acting Governor |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Taylor Robinson |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

July 1, 1856 Union Parish, Louisiana, USA |

| Died |

December 15, 1937 (aged 81) Little Rock, Pulaski County Arkansas |

| Resting place | Roselawn Memorial Park in Little Rock |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Louvenia Wallace Donaghey (married 1887-1937, his death) |

| Children | No children |

| Residence |

(1) Conway, Faulkner County |

| Alma mater | University of Arkansas |

| Profession | Developer |

George Washington Donaghey (July 1, 1856 – December 15, 1937) was the 22nd Governor of the U.S. state of Arkansas from 1909 to 1913.

Early life and education

Donaghey was born as the oldest of five children to Christopher Columbus and Elizabeth (née Ingram) Donaghey, in the Oakland Community in Union Parish in north Louisiana. His father's family was from Ireland and his mother's from Scotland. His father Christopher was a farmer who moved from Alabama to northern Louisiana where he purchased land and later moved to Arkansas where Christopher later served in the Confederate Army.[1]

In 1875, without letting his family know, Donaghey moved to Texas where he worked as a cowboy on the Chisholm Trail and farmer but later moved again to Arkansas in 1876 due to cowboy lifestyle and health issues. From 1882 to 1883, he attended the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville. He was a school teacher, carpenter, and he studied both architecture and structural engineering. In 1883, Donaghey established his residence at Conway, Arkansas, and adopted that city as his hometown where he later met his wife Louvenia Wallace but they never had children; one of the major streets there bears his name. He served one term as town marshal and was an unsuccessful prohibition candidate for mayor in 1885.[1]

Having himself lacked a formal education, Donaghey worked diligently to bring institutions of higher learning to Conway. He served on the boards of Philander Smith College in Little Rock, and Hendrix College (to which he donated $75,000 in 1910),[2] University of Central Arkansas, State Normal School (where he was the principal speaker for its 1908 dedication)[3] and Little Rock Junior College (both now part of University of Central Arkansas) in Conway, where his service extended from 1906 until his death. Additionally, he gave generously to both institutions.[1]

Business

Donaghey entered business as a contractor and constructed courthouses in Texas and Arkansas, including the first bank building in Conway in 1890. Shortly after, he detoured into the mercantile business as his contracting business was not profitable in its early years and suffered significant losses after building the second Faulkner County courthouse. When he returned, he reconstructed the Arkansas Insane Asylum after a tornado in 1894. He built ice plants and roads in Arkansas and water tanks and railroad stations for the Choctaw, Oklahoma and Gulf Railroad and often invested in farm and timber land.

In 1899, he was tasked with constructing the new state capitol, a plan that Governor Jeff Davis opposed and was eager to stop all plans. This started Donaghey's run for governor and he ran against Davis's ally William F. Kirby and Donaghey later won the election (106,512 votes) after defeating Republican John I. Worthington (42,979 votes) and Socialist J. Sam Jones (6,537).[1]

As governor

He was the first governor indisputably be labeled as progressive but he was also within the southern progressive tradition[4] as well as the businessman to become governor of Arkansas.[5] In 1908, Donaghey was elected governor on a "Complete the Capitol" program, having successfully explained to voters the need to complete the state capitol building project that had languished for many years. He won a three-way primary election which broke the power of former Governor Jefferson "Jeff" Davis on the Arkansas Democratic Party. Victory in the general election over Republican John L. Worthington was a mere formality, 110,418 (68.1 percent) to 41,689 (27.7 percent). Worthington had also run in 1906 against Davis.[6] Donaghey had to wait ten months to take office. In the meantime, he traveled the country, and as professor Calvin Ledbetter, Jr., of the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, points out in his book The Carpenter from Conway, Donaghey educated himself for the political office which awaited him. In June 1909, he appointed the fourth and final state capitol commission and hired Cass Gilbert for the architecture project.[4]

Donaghey was reelected in 1910, having defeated another Republican, Andrew L. Roland, 101,612 (67.4 percent) to 38,870 (26.5 percent. Another 9,196 ballots (6.1 percent) were cast for the Socialist candidate, Dan Hogan.[6] That same year, he negotiated with the Southern Regional Education Board to bring its campaign to Arkansas and had successful results in the state. That year, he also supported four agricultural high schools that later formed into Arkansas Tech University, Arkansas State University, Southern Arkansas University and University of Arkansas at Monticello. In 1910, he also improved public health by helping to create the Booneville Tuberculosis Sanatorium and later also negotiated with the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission to eradicate hookworm. During his term, Arkansas was the first state in the country to require smallpox vaccinations for all schoolchildren and school personnel and the Crossett malaria control experiment campaigned against the mosquitos. Donaghey's achievements included establishment of a new state board of education, support for high schools and the passage of a law making consolidation easier.[1]

Although several of the prisoners he pardoned from the convict lease program were black, Donaghey still supported segregation. In 1910 at the state Baptist Colored Convention in Little Rock, he said "It is not for any political purpose that I come to talk to you. It is not for the purpose of getting your votes, this you know as well as I do, because your people don't vote much. This, perhaps, is best for you. The greatest man in your race [Book T. Washington] has said that you should keep out of politics and in this I agree with him. I think it is best that you stay out of politics and look after the condition of your people, and in this you have as much as you can do".[7] In autumn 1911, he appeared with Booker T. Washington at the National Negro Business League and said to an audience of one thousand black men to "not waste their time running begginng for social equality". The Chicago Defender quoted him as saying "You must ride in the last two seats in our street cars; you must not sit in a Pullman car; you must not ride on the same deck, nor eat in the same restaurant, nor drink in the same saloon as me...You are a race of degenerates, your women are lewd and we cannot afford to have your white women and children associate with you".[8]

Donaghey's progressive stance procured passage of the Initiative and Referendum Act by which Arkansans can take governmental matters into their own hands and bypass the state legislature. He recruited William Jennings Bryan to help campaign for the amendment's adoption in 1910. Arkansas is the only state in the American South to grant its citizens such power. The initiative, which began in South Dakota, is otherwise particularly known in California and Colorado.

The Donaghey administration focused on roads, public health, and railroads. Donaghey was vehemently opposed to the use of prisoners for contract-leased labor, especially for building railroads. He particularly learned about convict lease while at a Southern governors' conference in West Virginia in autumn 1912. Unable to get the legislature to abolish the practice, Donaghey prior to leaving office pardoned 360 prisoners, 44 in country farms and 316 out of 850 in penitentiaries[4] and 37 percent of the incarcerated population. This left the lease system with insufficient available prisoners for utilization in construction. In 1913, a year after Donaghey left office, the legislature finally ended the practice and a new prison board was formed.[1]

In 1912, he was eager for a third term, hoping to take care of the much-needed tax reform and statewide prohibition but the legislature rejected his reforms and the electorate also rejected his prohibition plans. During his campaign for the third term, the state capitol project ran out of money and Donaghey's appropriation plans were not successful. What also helped Donaghey's defeat was that former governor Jeff Davis and his allies also campaigned for governor along with emerging powerbroker Joseph Taylor Robinson.[1]

After being governor

After his defeat by Joseph Taylor Robinson in 1912 in his attempt at a third term as governor, Donaghey persisted in his quest to complete the Capitol. A critical year was 1913. Senator Jeff Davis died two days into the year. Robinson, then governor, was named by the legislature as Davis' successor. J. M. Futtrell, president of the Arkansas Senate, became acting governor. The result was Futtrell and the Capitol Building Commission asked Donaghey to become a commission member and take charge of completing construction. He did. Donaghey in 1917 completed the Capitol, valued at more than $300 million today, for $2.2 million,[4] ending an 18-year effort. As a hallmark to completion, Donaghey personally built the governor's conference table, which sets today as the centerpiece of the governor's conference room in the north wing of the Capitol.

As a former governor, Donaghey served on a number of boards and commissions responsible for a variety of tasks such as constructions, education, and charities. He penned the book Build a State Capitol, which details the construction of the Arkansas capitol building.

Donaghey died from a heart attack in Little Rock in 1937 and is interred there at the Roselawn Memorial Park Cemetery. His estate is managed by George W. Donaghey Foundation in Little Rock.[9]

Former Arkansas Governor (1949-1953) Sid McMath said in his memoir Promises Kept: a Memoir that Donaghey was "without a doubt, one of the great governors of Arkansas and served as an inspiration to my administration and to others, particularly in the continuing struggle for human rights, and I decided to continue what he had begun".[10] One book called him ""arguably one of the best and most influential governors and philanthropists in Arkansas history".[11]

In 1999, the Log Cabin Democrat named him one of the ten most influential people of in Faulker County's history.[12]

Donaghey's Monument

In 1931, Donaghey, who felt a kinship to both Arkansas and Louisiana, established a monument at the Union Parish/Union County state line near his birthplace. The Art Deco-style monument contains intricate carvings and includes references to transportation in 1831 and 1931 and mentions Governor Huey P. Long, Jr., whose educational program Donaghey admired. The land was not registered with state parks offices in either state, timber companies cut trees around it, and the marker was forgotten.[13]

In 1975, an employee of the Louisiana Department of Transportation came across the abandoned monument and informed then State Representative Louise B. Johnson of Bernice of his discovery. In an article in the North Louisiana Historical Association Journal (since North Louisiana History), Johnson explained that she asked the Olinkraft Timber Company of West Monroe, Louisiana, to cease cutting trees on the property and to help with the restoration of the monument. She introduced a bill to cede the state's part of the property to the state parks system. Governor Edwin Washington Edwards signed what became Act 734 of 1975, and a re-dedication ceremony was held in which he and Johnson planted a tree. Months later, Arkansas sold its part of the land to Olin Mathieson Chemical Corporation, according to the Arkansas Historic Preservation Program. Since that time, chunks of the monument have been lost or spray-painted by vandals. Restoration efforts were unveiled in 2009.[13]

There were plans for a Donaghey State Park but the plans never happened and he died four years later.[14]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Timothy Paul Donovan; Willard B. Gatewood; Jeannie M. Whayne (1981). Governors of Arkansas (2nd). University of Arkansas Press. p. 130. ISBN 161075171X. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

- ↑ "Hendrix College and Its Relationship to Conway and Faulkner County". faulknerhistory.com. Retrieved June 24, 2015.

- ↑ "From the UCA Archives: Factors that led to UCA being located in Conway". thecabin.net. October 16, 2011. Retrieved June 24, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Whayne, Jeannie M. (2002). Arkansas: A Narrative History. University of Arkansas Press. p. 275. ISBN 1557287244. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

- ↑ "Carpenter from Conway". The Rotarian. 165 (6): 50. December 1994. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

- 1 2 Congressional Quarterly's Guide to U.S. Elections, p. 1601

- ↑ Gordon, Fon Louise (2007). Caste and Class: The Black Experience in Arkansas, 1880-1920. University of Georgia Press. p. 52. ISBN 0820331309. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

- ↑ Stephanie Cole; Natalie J. Ring (2012). The Folly of Jim Crow: Rethinking the Segregated South. Texas A&M University Press. p. 167. ISBN 1603446613. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

- ↑ "George Washington Donaghey". encyclopediaofarkansas.net. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

- ↑ McMath, Sid (2003). Promises Kept: a Memoir. University of Arkansas Press. p. 24. ISBN 1610753291. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

- ↑ Paulette H. Walker; Alan C. Paulson (1999). Historic Pulaski County. Arcadia Publishing. p. 83. ISBN 0738500062. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

- ↑ "Most Influential People". thecabin.net. June 24, 1999. Retrieved June 24, 2015.

- 1 2 "Matthew Hamil, "Monument Forgotten by Time"". Monroe News Star, August 31, 2009. Retrieved August 31, 2009.

- ↑ Stuart, Bonnye (2012). Louisiana Curiosities: Quirky Characters, Roadside Oddities & Other Offbeat Stuff. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 8. ISBN 0762791039. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

External links

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Jesse M. Martin Acting Governor |

Governor of Arkansas 1909–1913 |

Succeeded by Joseph Taylor Robinson |