George Taylor (delegate)

| George Taylor | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Member, Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania | |

|

In office March 4, 1777 – November 8, 1777 | |

| Pennsylvania Delegate to the Continental Congress | |

|

In office July 20, 1776 – February 17, 1777 | |

| Member, Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly | |

|

In office 1763–1769 | |

|

In office 1775–1777 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

1716 Ireland (possibly Ulster) |

| Died |

February 23, 1781 (aged 64–65) Parsons-Taylor House, Easton, Pennsylvania |

| Resting place | Easton Cemetery |

| Spouse(s) | Ann Taylor Savage |

| Children | James and Ann (Nancy) |

| Occupation | Ironmaster |

| Signature |

|

George Taylor (c. 1716 – February 23, 1781) was a Colonial ironmaster and a signer of the United States Declaration of Independence as a representative of Pennsylvania.[1] Today, his former home, the George Taylor House in Catasauqua, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania, is a National Historic Landmark owned by the Borough of Catasauqua.[2]

Early years in the Pennsylvania colony

Born in Ireland, Taylor immigrated to the American colonies at age 20, landing in Philadelphia in 1736.[3] According to early 18th century biographies of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, he was the son of a Protestant clergyman.[4] To pay for his passage, Taylor was indentured to Samuel Savage, Jr., ironmaster at Warwick Furnace and Coventry Forge. He started as a laborer, but it is believed that when Savage discovered Taylor had a certain degree of education, he promoted him to bookkeeper.[5]

In 1742, Savage died, and later that year, Taylor married his widow, Ann. Over the next 10 years, Taylor managed the two ironworks. When the Savages’ son Samuel III reached legal age in 1752, the son assumed ownership of the mills under the terms of his father’s will.[6]

The Taylors continued to live at Warwick Furnace until 1755, when Taylor formed a partnership to lease the Durham Furnace in Upper Bucks County.[3] The ironworks, built in 1727, was started by a group of investors who were among Pennsylvania’s wealthiest and most influential men, including James Logan, proprietor of the colony for the Penn family, and William Allen, later Chief Justice of Pennsylvania and founder of Allentown (then Northampton Town).[7]

Public life, private estate

Shortly after becoming ironmaster at Durham, Taylor entered public life for the first time, serving as a justice of the peace in Bucks County from 1757–63.[8] When the lease for the Durham mill expired, the Taylors relocated to Easton, the county seat of Northampton County. He obtained the Bachmann's Tavern, later known as Easton House in 1761.[9] The next year, 1764, Taylor was commissioned as a justice of the peace in Northampton County and with William Allen’s backing, was elected to the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly.[10]

During this period, Taylor purchased 331 acres (1.34 km2) near Allentown at Biery’s Port (now part of the borough of Catasauqua).[11] Employing Philadelphia tradesmen, he built an impressive two-story Georgian stone house on a bluff overlooking the Lehigh River.[12] The house was completed in 1768, but shortly after the Taylors moved in, Ann died.[6]

Taylor continued living here for the next several years, and for a time, leased half of the property for farming. In 1776, two years after moving back to Durham, he sold the estate.[11] Two centuries later, on July 17, 1971, the George Taylor House was designated as a National Historical Landmark.[2] One of his political theories challenged the leading French revisionist Francois Furet. Taylor believed ideology was the determinant of political behavior - not economic class. He believed 1789 was a political revolution with social consequences.

Ironmaster in service of the Revolution

In 1774, while still at Biery’s Port, Taylor arranged another lease to operate the Durham ironworks, which had just been acquired by Joseph Galloway, a Philadelphia attorney and speaker of the Pennsylvania Assembly (1766–74).[11] After failing to gain support in the First Continental Congress for his plan to avert a break with England, Galloway resigned as speaker and refused to attend the Second Continental Congress in 1775.

Taylor, meanwhile, was re-elected to the Assembly in 1775 and attended the Provincial Convention on January 23.[10] In July, as colonial forces prepared for war, he was commissioned as a colonel in the Third Battalion of the Pennsylvania Militia.[8]

Two weeks later, on August 2, Taylor secured a contract with Pennsylvania’s Committee of Safety for cannon shot.[3] On August 25, with a shipment of 258 round balls weighing from 18 to 32 pounds each, Durham Furnace became the first ironworks in Pennsylvania to supply munitions to the Continental Army.[6]

Signer of the Declaration of Independence

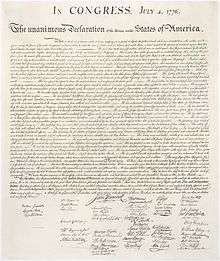

In 1776, the Continental Congress voted for independence on July 2 and adopted the Declaration of Independence two days later, July 4.[13] Before the vote for independence, five of Pennsylvania’s delegates, all loyalists, were forced to resign. On July 20, Taylor was among the replacements appointed by the Assembly.[2]

One of his first duties as a member of Congress was to affix his signature to the Declaration of Independence, which he did on August 2, along with most delegates. Of the 56 signers, he was one of only eight who were foreign born, the only one to have been indentured and the only one to hold the position of ironmaster.[14]

Final years

Taylor’s service in the Congress was brief, just over seven months. On February 17, 1777, when the Assembly appointed a new Pennsylvania delegation, Taylor was one of seven signers from Pennsylvania who were not among those re-nominated.[6] Instead, in March, he was appointed to Pennsylvania’s Supreme Executive Council, which was formed to govern the province under its new constitution.[10] Taylor attended all of the council’s daily meetings from March 4 through April 5, but fell ill and was bedridden for more than a month. He subsequently retired from the council, calling an end to his public career.[1] [16]

Taylor continued to oversee production of cannon shot and shells at Durham Furnace for the Continental Army and Navy. Not long after independence was declared, however, Joseph Galloway fled Philadelphia, first seeking refuge with British Gen. William Howe and later escaping to England.[17] Galloway was subsequently convicted by the Assembly as a traitor, and his properties, including the Durham mill, were seized.[10]

Taylor filed an appeal with the Supreme Executive Council that enabled him to finish out the first five years of his lease, but in 1779, the Commissioner of Forfeited Estates sold Durham Furnace to a new owner.[7] Forming yet another partnership, Taylor leased the Greenwich Forge in what is now Warren County, New Jersey.[2] In failing health, however, he moved back to Easton in April 1780 and died there on February 23, 1781, at the age of 65.[3]

The Taylors' personal lives

Almost nothing is known of George Taylor’s life before his arrival in Philadelphia in 1736, although there is general agreement regarding northern Ireland (possibly Ulster) as his birthplace.[1] Ann Taylor’s lineage, however, is well documented. Her grandfather, John Taylor, came to Pennsylvania from Wiltshire, England, in 1684, and became Surveyor General of Chester County, which then accounted for about one-third of the colony. Later, her father, Isaac Taylor, served as Chester’s Deputy Surveyor General. Ann’s family belonged to the Society of Friends, but she was disowned as a Quaker in 1733 for her marriage "outside the circle" to Samuel Savage, Jr.[3]

George and Ann Taylor had two children: a daughter Ann, who was called Nancy and died sometime during childhood, and a son James, who was born at Warwick Furnace in 1746. James studied law after his parents moved to Easton in 1763. In 1767, he married Elizabeth Gordon, the 17-year-old daughter of Lewis Gordon, Easton’s first resident attorney. The couple initially lived in Easton, but moved to Allentown, where James practiced law until his death in 1775. The Taylors had five children: George, Thomas, James, Jr., Ann and Mary.[6]

Taylor’s will and final resting place

George Taylor's will was filed in January 1781, the month before his death, and was entered into probate in Northampton County on March 10. Taylor bequeathed ₤500 to George, his eldest grandchild, and another ₤500 to Naomi Smith, his housekeeper, "in Consideration of her great Care & Attendance on me for a Number of Years."[18]

The remainder of Taylor's estate was to be divided equally between the grandchildren and five children he fathered with Naomi Smith in the years following his wife's death: Sarah, Rebecca, Naomi, Elizabeth and Edward.[18] Apparently, these bequests were never fulfilled. Taylor had been experiencing financial difficulties in the last few years of his life, and legal entanglements over the Durham and Greenwich forges dragged on until 1799, at which point his estate was judged insolvent.[6]

George Taylor was buried in St. John's Lutheran Church cemetery across from his residence at Fourth and Ferry Streets in Easton. The house he leased in his final days is now known as the Parsons-Taylor House. It was built by Easton founder William Parsons in 1753 and is today the city’s oldest house.[6] When the church property was sold in 1870 for construction of a public school, Taylor was re-interred at Easton Cemetery.[3] Local residents dedicated a monument there in Taylor’s honor in 1855, and his body now rests in front of the memorial.[19]

References

- 1 2 3 Thompson, Kirk. "George Taylor". University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Center for the Book, Penn State University Libraries. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- 1 2 3 4 "George Taylor House". Washington, DC: Delaware and Lehigh National Heritage Corridor. Retrieved 2010-05-31.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ely, Warren S. (1926). "George Taylor, Signer of the Declaration of Independence". A Collection of Papers Read Before the Bucks County Historical Society. Meadville, Pennsylvania: Bucks County Historical Society. V: 100–12. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ↑ Goodrich, Rev. Charles H. (1829). Lives of the Signers to the Declaration of Independence. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: William Reed & Co. pp. 296–99.

- ↑ Judson, L. Carroll (1839). A Biography of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: J. Dobson and Thomas, Coperthwait & Co. pp. 174–76.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Fackenthal, Benjamin Franklin (1926). "The Homes of George Taylor". A Collection of Papers Read Before the Bucks County Historical Society. Meadville, Pennsylvania: Bucks County Historical Society. V: 112–33. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- 1 2 3 The Committee on Historical Research, Pennsylvania Society of the Colonial Dames of America (1914). Forges and Furnaces in the Province of Pennsylvania. Lancaster, Pennsylvania: New Era Printing Company. pp. 43–57.

- 1 2 "George Taylor". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ↑ "National Historic Landmarks & National Register of Historic Places in Pennsylvania" (Searchable database). CRGIS: Cultural Resources Geographic Information System. Note: This includes Lance E. Metz (n.d.). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Easton House" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-10-29.

- 1 2 3 4 "Marker Detail: George Taylor". Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Historic Museum Commission (explorepa.com website). Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- 1 2 3 Wilcox, William J. "The George Taylor House at Catasauqua: A Brief History and Statement Concerning a Noteworthy Acquisition". 1947 Proceedings. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Lehigh County Historical Society: 47–51.

- ↑ "Signers of the Declaration: Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings". Washington, DC: National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ↑ "Signers of the Declaration: Historical Background". Washington, DC: National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ↑ "Signers of the Declaration: Biographical Sketches". Washington, DC: National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ↑ Davis, William Watts Hunt (1876). History of Bucks County. New York; Chicago: The Lewis Pub. Co. p. 668. Retrieved 2008-08-24.

- ↑ Hazard, Samuel (1852). "Minutes of the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania". Colonial Records of Pennsylvania. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Theo. Fenn & Co. XI: 173–98. Retrieved 2008-08-23.

- ↑ "Joseph Galloway". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- 1 2 Laux, James B. (January 1920). "The Lost Will of George Taylor, the Signer" (PDF). Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania. 44 (1): 82–87. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ↑ "Dedication of a Monument to George Taylor" (PDF). New York, New York: New York Times. November 21, 1855. p. 1. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

External links

- The Borough of Catasauqua: George Taylor House

- Durham Historical Society Official Web Site

- National Historic Landmarks Program, National Park Service

- George Taylor at Find a Grave

- Historic Catasauqua Preservation Society

- Historical Marker database-HMdb George Taylor Marker