Geoffroi de Charny

This article is about the French knight who died in 1356 at the Battle of Poitiers. For the Knight Templar of similar name who may or may not have been his uncle, and who was burned at the stake in 1314, see Geoffroi de Charney.

Geoffroi de Charny (c. 1300 – 19 September 1356) was a French knight and author of at least three works on chivalry. He was born around 1300. His father, Jean de Charny was the Lord of Lirey in Burgundy and his mother was Margaret de Joinville. His grandfather on his mother's side, Jean de Joinville, was a close friend of King Louis IX and author of his biography. Geoffroi was a knight in the service of King Jean II of France and a founding member of the Order of the Star, an order of chivalry founded on 6 November 1351 by Jean II of France similar to the Order of the Garter (1347) by Edward III of England. He was also the carrier of the Oriflamme, the standard of the crown of France, an immensely privileged, not to mention dangerous, honour, as it made the holder a key target of enemy forces on the battlefield. Geoffroi de Charny was one of Europe's most admired knights during his lifetime, with a widespread reputation for his skill at arms and his honour. It was said that in his time he was known as a "true and perfect Knight".[1]

Military career

Geoffroi de Charny fought at Hainault and in Flanders, and participated in a crusade under Humbert II of Viennois in the late 1340s. Humbert, was a terrible soldier and leader (1) and the crusaders signed a treaty with the Turks in 1348, despite the capture of Smyrna under a previous commander.

We know from the Chronicles of Froissart that de Charny traveled to Scotland by order of the French King on at least two occasions and was well known to the Scottish nobles of the time. The chronicle describes the French Knight's visit and de Charny briefly in this passage written in Middle English: .. "Mctray Duglas and the erle Morette knewe of their comynge, they wente to the havyn and mette with them, and receyved them swetely, sayeng howe they were right welcome into that countrey. And the barons of Scotlande knewe ryght well sir Geffray de Chamey, for he had been the somer before two monethes in their company: sir Greffray acquaynted them with the admyrall, and the other knyghtes of France".[2]

It is recorded and recently translated that Geoffroi was taken prisoner on two occasions. Once was at the battle of Morlaix. It is further recorded that in 1342 Geoffroi was taken prisoner in Brittany, then taken to Goodrich Castle in England, where his captor was Richard Talbot. An English letters patent of October 1343 describes him as having 'gone to France to find the money for his ransom'.[3] It was a rare occurrence that a man would be thus trusted and since he went on to fight other battles, someone apparently paid Geoffroi's ransom, and he was knighted the very next year.[4]

Another incident which provides insight into Geoffroi's mind is the retribution exacted upon Lombardy-born Aimery of Pavia, the man who betrayed him in his attempted recapture of Calais on New Year's Eve, 1349. Geoffroi conducted a dangerous raid on Aimery's castle. Geoffroi took Aimery captive to St. Omer, decapitated him, quartered his body, and displayed it on the town gates. As Professor Kaeuper adds: 'To show that all this was a private matter and not a part of the business of war (there was currently a truce), Charny took possession only of Aimery himself, not his castle.'[5]

Negotiations prior to the Battle of Poitiers

Shortly before his death, Sir Geoffroi's dire predictions proved to be truly prophetic and his recorded words exemplify what only a "true and perfect" medieval knight might be expected to say. They are recorded in the writings of the life of Sir John Chandos and were made in the final moments of a meeting of both sides in an effort to avoid the bloody conflict at Poitiers during The Hundred Years' War. The extraordinary narrative occurred just before that battle and reads as follows:

| “ | ... The conference attended by the King of France, Sir John Chandos, and many other prominent people of the period, The King, to prolong the matter and to put off the battle, assembled and brought together all the barons of both sides. Of speech there he (the King) made no stint. There came the Count of Tancarville, and, as the list says, the Archbishop of Sens (Guillaume de Melun) was there, he of Taurus, of great discretion, Charny, Bouciquaut, and Clermont; all these went there for the council of the King of France. On the other side there came gladly the Earl of Warwick, the hoary-headed (white or grey headed) Earl of Suffolk was there, and Bartholomew de Burghersh, most privy to the Prince, and Audeley and Chandos, who at that time were of great repute. There they held their parliament, and each one spoke his mind. But their counsel I cannot relate, yet I know well, in very truth, as I hear in my record, that they could not be agreed, wherefore each one of them began to depart. Then said Geoffroi de Charny: 'Lords,' quoth he, 'since so it is that this treaty pleases you no more, I make offer that we fight you, a hundred against a hundred, choosing each one from his own side; and know well, whichever hundred be discomfited, all the others, know for sure, shall quit this field and let the quarrel be. I think that it will be best so, and that God will be gracious to us if the battle be avoided in which so many valiant men will be slain.[6] | ” |

Death

Sir Geoffroi de Charny was killed at the Battle of Poitiers in 1356, a great defeat for the French in which the French king was taken prisoner to England and the French nobility lost here as well as at Crecy was almost completely wiped out. Froissart’s words vividly (but inaccurately) describe Geoffroi’s last actions, his bravery to his King and Country and his dedication to the Oriflamme at the Battle of Poitiers on September 19, 1356: “There Sir Geoffroi de Charny fought gallantly near the king (note: and his fourteen-year-old son). The whole press and cry of battle were upon him because he was carrying the king’s sovereign banner, the Oriflamme. Geoffroi also had before him his own banner, gules, three escutcheons argent. So many English and Gascons came around him from all sides that they cracked open the king’s battle formation and smashed it; there were so many English and Gascons that at least five of these men at arms attacked one [French] gentleman. Sir Geoffroi de Charny was killed with the banner of France in his hand, as other French banners fell to earth.”[7]

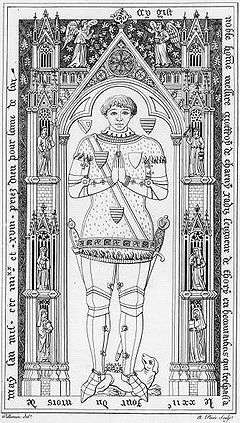

Brass Effigy

The Brass Effigy is of the son, French Knight Geoffroi de Charny II. It is presented for historical reference only since there are no known images of the father. It is said to be an authentic likeness to the father as well and the son. The Effigy translation was generously provided by author Ian Wilson. It states as follows: ‘Here lies the noble man Monsieur Geoffroy de Charny at one time seigneur of Thory, in the district of Beauvais, who died the 22nd day of the month of May 1398. Pray God for his soul.’.[8]

The Effigy is frequently represented elsewhere as being of the father but the translation clearly shows it is of Geoffroi II, the son.

Shroud of Turin

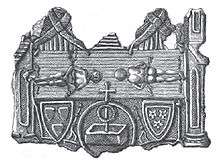

Geoffroi de Charny and his wife Jeanne de Vergy are the first reliably recorded owners of the Turin Shroud.[9][10] The first public exhibition of the Shroud is memorialized in The Pilgrimage Medal shown here and dating from that time. The medal shows the image of the Shroud[11] with very precise indications in spite of its small dimensions. On this medal one can see a frontal and dorsal view of the body, the linen herring patterns, four marks of burns as well as the coats of arms of the Charny and Vergy families. This pilgrimage medal is exhibited at the Cluny museum in Paris (France).

Literary works

Geoffroi de Charny's most famous work is his 'Book of Chivalry', written around 1350, which is, along with the works of Ramon Llull and Chretien de Troyes one of the best sources to understand how knights themselves described and prioritised chivalric values in the 14th century. Geoffroi discusses many subjects but above all he values skill at arms over all other knightly virtues and war over all other forms of contest at arms.

He was also the author of 'Demands pour la joute, les tournois, et la guerre', in English, 'Questions for the joust, tournaments and war', a book on knightly pursuits. Only the questions survive; however, the way that the questions are phrased, as well as Geoffroi's actions in his lifetime, allow scholars to reach further conclusions about Geoffroi's conception of chivalry and war.

References

- ↑ Barbara W. Tuchman, A Distant Mirror, the Calamitous 14th Century (Published Alfred A. Knopf (1978].

- ↑ The Chronicle of Froissart. translated by Sir John Nourchier Lord Berners introduction by William Paton Ker Vol. IV (London pub. David Nutt Sign of the Phoenix Long Acre 1902) Chpt II par 22 - out of copyright/

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls 1343-45: 130]

- ↑ Richard W. Kaeuper and Elspeth Kennedy, The Book of Chivalry of Geoffroi de Charny: Text, Context and Translation (Philadelphia, University of Philadelphia Press) Introduction.

- ↑ Richard W. Kaeuper and Elspeth Kennedy, The Book of Chivalry of Geoffroi de Charny: Text, Context and Translation (Philadelphia, University of Philadelphia Press) Introduction.

- ↑ Life of the Black Prince by the Herald of Sir. John Chandos. edited from the Manuscript in Worchester College with Linguistic and Historical Notes, 1910. Not in Copyright p. 141-142

- ↑ Jean Froissart; Geoffrey Brereton, Chronicles ( Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, UK, 1978), p. 140

- ↑ Translation of the brass effigy was kindly done by Ian Wilson (author) for this editor and Wikipedia. http://www.shroud.com/pdfs/n66part5.pdf

- ↑ Dubarle, André-Marie, « La première captivité de Geoffroy de Charny et l'acquisition du linceul », Montre-nous ton visage, 8, 1993, p. 6-18; « The first captivity of Geoffroy de Charny and the acquisition of the Shroud », rév. et trad. ang. par Daniel C. Scavone, publication électronique.

- ↑ 1357 The First public exhibition of the Shroud in Lirey collegiate church/a

- ↑ Historical and Scientific Study of the Shroud of Turin, electronic publication for PC.

Further reading

- Richard W. Kaeuper & Elspeth Kennedy, A Knight's Own Book: Chivalry of Geoffroi de Charny, Pennsylvania U.P.

- Barbara Tuchman, A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century (PublishedAlfred A. Knopf (1978)

- Richard W. Kaeuper & Elspeth Kennedy, The Book of Chivalry of Geoffroi de Charny: Text, Context, and Translation (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania U.P., 1996) (Middle Ages Series).

- Steven Muhlberger, Jousts and Tournaments: Charny and chivalric sport in fourteenth-century France, Union City, Calif: The Chivalry Bookshelf, 2003.

- Froissart's Chronicles

External links

- The French knight Geoffrey de Charny

- Historical and Scientific Study of the Shroud of Turin and the public exhibition of the Shroud in Lirey, electronic publication for PC.

- The mystery of the Templar Mandylion

- http://www.nipissingu.ca/department/history/MUHLBERGER/2006/05/geoffroi-de-charny-speaks_10.htm