Gentoo penguin

| Gentoo penguin | |

|---|---|

| | |

| Brown Bluff, Tabarin Peninsula | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Sphenisciformes |

| Family: | Spheniscidae |

| Genus: | Pygoscelis |

| Species: | P. papua |

| Binomial name | |

| Pygoscelis papua (Forster, 1781) | |

| |

| Distribution of the gentoo penguin | |

The long-tailed gentoo penguin (/ˈdʒɛntuː/ JEN-too) (Pygoscelis papua) is a penguin species in the genus Pygoscelis, most closely associated with the Adélie penguin (P. adeliae) and the chinstrap penguin (P. antarcticus). The first scientific description was made in 1781 by Johann Reinhold Forster with a reference point of the Falkland Islands. They call in a variety of ways, but the most frequently heard is a loud trumpeting which is emitted with its head thrown back.[2]

The application of gentoo to the penguin is unclear. The Oxford English Dictionary notes that gentoo used to be an Anglo-Indian term used as early as 1638 to distinguish Hindus in India from Muslims. The English term may have originated from the Portuguese gentil (compare "gentile").

Taxonomy

The gentoo penguin is one of three species in the genus Pygoscelis. Mitochondrial and nuclear DNA evidence suggests the genus split from other penguins around 38 million years ago, about 2 million years after the ancestors of the genus Aptenodytes. In turn, the Adelie penguins split off from the other members of the genus around 19 million years ago, and the chinstrap and gentoo finally diverged around 14 million years ago.[3]

Two subspecies of this penguin are recognised: Pygoscelis papua papua and the smaller Pygoscelis papua ellsworthii.

Description

The gentoo penguin is easily recognized by the wide white stripe extending like a bonnet across the top of its head and its bright orange-red bill. They have pale whitish-pink webbed feet and a fairly long tail - the most prominent tail of all penguins. Chicks have grey backs with white fronts. As the gentoo penguin waddles along on land, its tail sticks out behind, sweeping from side to side, hence the scientific name Pygoscelis, which means "rump-tailed".[4]

Gentoos reach a height of 51 to 90 cm (20 to 35 in),[5][6] making them the third-largest species of penguin after the two giant species, the emperor penguin and the king penguin. Males have a maximum weight of about 8.5 kg (19 lb) just before molting, and a minimum weight of about 4.9 kg (11 lb) just before mating. For females, the maximum weight is 8.2 kg (18 lb) just before molting, but their weight drops to as little as 4.5 kg (9.9 lb) when guarding the chicks in the nest.[7] Birds from the north are on average 700 g (1.5 lb) heavier and 10 cm (3.9 in) taller than the southern birds. Southern gentoo penguins reach 75–80 cm (30–31 in) in length.[8] They are the fastest underwater swimming penguins, reaching speeds of 36 km/h (22 mph).[9] Gentoos are adapted to very harsh cold climates.

Breeding

The breeding colonies of gentoo penguins are located on ice-free surface. Colonies can be directly on the shoreline or can be located considerably inland. They prefer shallow coastal areas and often nest between tufts of grass. In South Georgia, for example, breeding colonies are 2 km inland. Whereas in colonies farther inland, where the penguins nest between tufts of grass, they shift location slightly every year because the grass may get trampled over time.

Gentoos breed on many sub-Antarctic islands. The main colonies are on the Falkland Islands, South Georgia, and Kerguelen Islands; smaller populations are found on Macquarie Island, Heard Islands, South Shetland Islands, and the Antarctic Peninsula. The total breeding population is estimated to be over 300,000 pairs. Nests are usually made from a roughly circular pile of stones and can be quite large, 20 cm (7.9 in) high and 25 cm (9.8 in) in diameter. The stones are jealously guarded and their ownership can be the subject of noisy disputes between individual penguins. They are also prized by the females, even to the point that a male penguin can obtain the favors of a female by offering her a nice stone.

Two eggs are laid, both weighing around 130 g (4.6 oz). The parents share incubation, changing duty daily. The eggs hatch after 34 to 36 days. The chicks remain in the nests for about 30 days before forming creches. The chicks molt into subadult plumage and go out to sea at about 80 to 100 days.

Diet

Gentoos live mainly on crustaceans, such as krill, with fish making up only about 15% of the diet. However, they are opportunistic feeders, and around the Falklands are known to take roughly equal proportions of fish (Patagonotothen sp., Thysanopsetta naresi, Micromesistius australis), squat lobsters (Munida gregaria), and squid (Loligo gahi, Gonatus antarcticus, Moroteuthis ingens).

Physiology

Because Gentoos live in the frozen Antarctic, there is not much fresh water available to them. Much of the Gentoos' diets are high in salt so to counteract this, they eat organisms that have relatively the same salinity as sea water. This can still lead to complications associated with high sodium concentrations in the body, especially for Gentoo chicks. To combat this, Gentoos, as well as many other marine bird species, have a highly developed salt gland located above their eyes that takes the high concentration of sodium within the body and produces a highly saline-concentrated solution that drips out of the body from the tip of the beak.[10]

Gentoo penguins do not store as much fat as the Adelie penguin, their closest relative, because Gentoos require less energy investment when hunting. The net gain of energy after hunting is greater in Gentoos than Adelies, so Gentoos do not need large energy stores as adults.[11] As embryos, Gentoos require a lot of energy in order to develop. Oxygen consumption is high for a developing Gentoo embryo. As the embryo grows and requires more oxygen, the amount of consumption increases exponentially until the Gentoo chick hatches. By then, the chick is consuming around 1800 mL O2 per day.[12]

Threats

.jpg)

In the water, sea lions, leopard seals, and killer whales are all predators of the Gentoo. On land, no predators of full-grown Gentoo penguins exist. Skuas can steal their eggs; however, some other seabirds have managed to snatch their young. Skuas on King George Island have been observed attacking and injuring adult Gentoo penguins in apparent territorial disputes.[13]

Conservation status

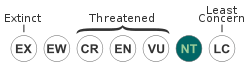

As of 2012, the IUCN Red List lists the Gentoo as near threatened, due to a rapid decline in some key populations which is believed to be driving a moderate overall decline in the species population. Examples include the population at Bird Island, South Georgia, where the population fell by two-thirds in 25 years.[14]

Gallery

Adult Gentoo confronting a giant petrel.

Adult Gentoo confronting a giant petrel._on_nest.jpg) Gentoo penguin on nest

Gentoo penguin on nest A Gentoo penguin swimming

A Gentoo penguin swimming Middle young Gentoos on Petermann Island

Middle young Gentoos on Petermann Island Gentoo colony on Carcass Island in the Falklands

Gentoo colony on Carcass Island in the Falklands A leopard seal capturing an adult Gentoo penguin

A leopard seal capturing an adult Gentoo penguin

References

- ↑ BirdLife International (2012). "Pygoscelis papua". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ Woods, R.W. (1975) Birds of the Falkland Islands, Antony Nelson, Shropshire, UK.

- ↑ Baker AJ, Pereira SL, Haddrath OP, Edge KA (2006). "Multiple gene evidence for expansion of extant penguins out of Antarctica due to global cooling". Proc Biol Sci. 273 (1582): 11–17. doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3260. PMC 1560011

. PMID 16519228.

. PMID 16519228. - ↑ Gentoo penguin videos, photos and facts - Pygoscelis papua - ARKive

- ↑ ADW: Pygoscelis papua: Information

- ↑ http://ourworld.compuserve.com/homepages/peter_and_Barbara_Barham/GENTOO.htm

- ↑ Gentoo penguin videos, photos and facts - Pygoscelis papua - ARKive

- ↑ Antarctica fact file wildlife, gentoo penguins

- ↑ BBC Nature - Gentoo penguin videos, news and facts

- ↑ Schmidt-Nielsen, K. (1960). The Salt-Secreting Gland of Marine Birds. Circulation, 21(5), 955-967. doi:10.1161/01.cir.21.5.955

- ↑ D’Amico, V. L., Coria, N., Palacios, M. G., Barbosa, A., & Bertellotti, M. (2014). Physiological differences between two overlapped breeding Antarctic penguins in a global change perspective. Polar Biol Polar Biology, 39(1), 57-64. doi:10.1007/s00300-014-1604-9

- ↑ Actams, N. J. (1992). Embryonic metabolism, energy budgets and cost of production of king Aptenodytes patagonicus and gentoo Pygoscelis papua penguin eggs. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Physiology, 101(3), 497-503. doi:10.1016/0300-9629(92)90501-g

- ↑ February 2014 observation and photo report by Robert Runyard, translator for INACH (Chilean Antarctic Institute).

- ↑ Pygoscelis papua (gentoo penguin)

This article incorporates text from the ARKive fact-file "Gentoo penguin" under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License and the GFDL.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- 70South – more info on the gentoo penguin

- Gentoo penguins from the International Penguin Conservation website

- www.pinguins.info: information about all species of penguins

- Gentoo penguin images

- Biodiversity at Ardley Island Small place near King Luis Island, special protected area and colony of gentoo penguins.

- Gentoo penguin webcam from the Antarctic – worldwide first webcam with wild penguins; photo quality

- Gentoo penguin media at ARKive

_03.jpg)