Ganz Works

| |

| Private company (former state company) | |

| Industry | transport vehicle manufacturing, iron and steel manufacturing |

| Founded | 1844 |

| Headquarters | Budapest, Hungary |

| Products | tramcars, trains, ships, electrical generators |

The Ganz (Ganz vállalatok, "Ganz companies") electric works in Budapest is probably best known for the manufacture of tramcars, but was also a pioneer in the application of three-phase alternating current to electric railways. Ganz also made ships (Ganz Danubius), bridge steel structures (Ganz Acélszerkezet) and high voltage equipment (Ganz Transelektro). Some engineers employed by Ganz in the field were Kálmán Kandó and Ottó Bláthy. The company is named after Ábrahám Ganz. In 2006, the power transmission and distribution sectors of Ganz Transelektro were acquired by Crompton Greaves,[1] but still doing business under the Ganz brand name, while the unit dealing with electric traction (propulsion and control systems for electric vehicles) was acquired by Škoda Transportation and is now a part of Škoda Electric.[2]

History

Before 1919, the company built ocean liners, dreadnought type battleships and submarines, power plants, automobiles[3][4] and many types of fighter aircraft.[5]

The company was founded by Abraham Ganz in 1844. He established his own iron foundry in Buda in the Kingdom of Hungary. Consequently, this factory played an important role in building the infrastructure of the Hungarian Kingdom and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. At this time the agricultural machines, steam-locomotives, pumps and the railway carriages were the main products. At the beginning of the 20th century, 60 to 80% of the factory's products were sold for export.

At the end of the 19th century, the products of the Ganz and Partner Iron Mill and Machine Factory (hereinafter referred to as Ganz Works) promoted the expansion of alternating-current power transmissions.

Determinant Engineers

Many engineers contributed to the Ganz Works:

András Mechwart invented the hard cast rolling mill, which revolutionized the milling industry.[6]

[7]

Károly Zipernowsky participated in construction of 60 power stations; he acted as the first professor of electric engineering of the Budapest University of Technology and Economics (hereinafter referred to as BMGE).[8]

Miksa Déri developed the repulsion motor, it was used for elevators of buildings with single phase alternating current.[9] He also participated in construction of Vienna's electric supply.

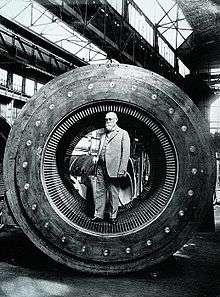

His whole life, Ottó Titusz Bláthy worked at the Ganz Works. His basic job was the construction and patenting of induction flow meter of 1889 used today. He invented the Turbogenerator in 1901. In the 1930s, he initiated the Hungarian production of turbogenerators.[10]

Kálmán Kandó was the first who recognised that an electric train system can only be successful if it can use the electricity from public networks. After realising that, he also provided the means to build such a rail network by inventing a rotary phase converter suitable for locomotive usage. He developed high-voltage three phase alternating current motors and generators for electric locomotives; he is known as "the father of the electric train".

Power plants, generators turbines and transformers

In 1878, the company's general manager András Mechwart (1853–1942) founded the Department of Electrical Engineering headed by Károly Zipernowsky (1860–1939). Engineers Miksa Déri (1854–1938) and Ottó Bláthy (1860–1939) also worked at the department producing direct-current machines and arc lamps.

The first turbo-generators were water turbines which propelled electric generators. The first Hungarian water turbine was designed by the engineers of the Ganz Works in 1866, the mass production with dynamo generators started in 1883.[11]

The missing link of a full Voltage sensitive - voltage intensive (VSVI) system was the reliable AC Constant Voltage generator. Therefore the invention of the constant voltage generator by the Ganz Works in 1883[12] had crucial role in the beginnings of the industrial scale AC power generating, because only these type of generators can produce a stated output voltage, regardless of the value of the actual load.[13]

In cooperation, Zipernovsky, Déri and Bláthy constructed and patented the transformer (see Picture 2). The name "transformer" was created by Ottó Titusz Bláthy.

The transformer patents described two basic principles. Loads were to be connected in parallel, not in series as had been the general practice until 1885. Additionally, the inventors described the closed armature as an essential part of the transformer. Both factors assisted the stabilization of voltage under varying load, and allowed definition of standard voltages for distribution and loads. The parallel connection and efficient closed core made construction of electrical distribution systems technically and economically feasible.

It is noteworthy that the Ganz Works built the first transformers using iron cover of enameled mild iron wire, and started to use laminated core of today at the end of 1885.

In 1886, the ZBD engineers designed, and the Hungarian Ganz company supplied electrical equipment for the world's first power station that used AC generators to power a parallel connected common electrical network, the Italian steam-powered Rome-Cerchi power plant.[14]

Following introduction of transformer, the Ganz Works changed over to production of alternating-current equipment successfully. (For instance, Rome's electric supply was resolved by hydroelectric plant and energy transfer of long distance.)[15]

The first specimen of the kilowatt-hour meter (electricity meter) produced on the basis of Hungarian Ottó Bláthy's patent and named after him was presented by the Ganz Works at the Frankfurt Fair in the autumn of 1889, and the first induction kilowatt-hour meter was already marketed by the factory at the end of the same year. These were the first alternating-current wattmeters, known by the name of Bláthy-meters.[16]

The Hungarian "ZBD" Team (Károly Zipernowsky, Ottó Bláthy, Miksa Déri). They were the inventors of the first high efficiency, closed core shunt connection Transformer. The three also invented the modern power distribution system: Instead of former series connection they connect transformers that supply the appliances in parallel to the main line.[17]

The Hungarian "ZBD" Team (Károly Zipernowsky, Ottó Bláthy, Miksa Déri). They were the inventors of the first high efficiency, closed core shunt connection Transformer. The three also invented the modern power distribution system: Instead of former series connection they connect transformers that supply the appliances in parallel to the main line.[17] Prototypes of the world's first high efficiency transformers (Széchenyi István Memorial Exhibition, Nagycenk, Hungary, 1885)

Prototypes of the world's first high efficiency transformers (Széchenyi István Memorial Exhibition, Nagycenk, Hungary, 1885) Ganz 21.000 KW Transformer, Hungary in 1911, weight: 38t

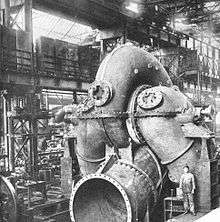

Ganz 21.000 KW Transformer, Hungary in 1911, weight: 38t The construction of a Ganz water turbo generator in 1886

The construction of a Ganz water turbo generator in 1886 Ottó Bláthy in the armature of a Ganz turbo generator (1904)

Ottó Bláthy in the armature of a Ganz turbo generator (1904) A generator assembly hall of the Ganz Works in 1922

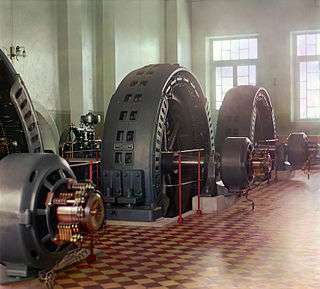

A generator assembly hall of the Ganz Works in 1922 Early 20th century alternator made by Ganz in Budapest, Hungary, in the generating hall of a Russian hydroelectric station on the Morghab River (1911 colour photo by Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky)

Early 20th century alternator made by Ganz in Budapest, Hungary, in the generating hall of a Russian hydroelectric station on the Morghab River (1911 colour photo by Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky) Generator in Zwevegem, West Flanders, Belgium

Generator in Zwevegem, West Flanders, Belgium

Internal combustion engines and vehicles

Beginning of gas engine manufacturing is linked to the names of Bánki and Csonka in 1889.

Produced engines which designs and licences were sold for Western European partners (mostly U.K. and Italy):

- 1889 the first four-stroke gas engine was built by the Ganz factory

- 1893 the manufacture of the paraffin- and petrol-fuelled engine with carburettor

- 1898 the start of the manufacture of the engines with the Bánki water injection system

- 1908 the introduction of a new petrol engine type, the series Am

- 1913 the manufacture of the Büssing petrol engines for truck vehicles

- 1914–18 the manufacture of fighter plane engines

- 1916 the manufacture of petrol engines, type Fiat

- 1920 the usage of petrol engines for suction gas engine operation

- 1924 Mr. György Jendrassik started his engine development activity

- 1928 there was finished the first railway Diesel engine according to the plans of Ganz-Jendrassik

- 1929 the first export delivery of a railway engine according to the System of Ganz-Jendrassik

- 1934 there was an engine reliability World Competition in the USSR where the Ganz engine achieved the best consumption in its category

- 1944 the first application of the engine type XII JV 170/240 in the motor-train set

- 1953 modernization of the Diesel engines System Ganz-Jendrassik type

- 1959 the union of the Ganz factory and the MÁVAG company, establishing of the Ganz-MÁVAG

Railways

Ganz Company started to construct steam engines and locomotive carriages since the 1860s.

Between 1901 and 1908, Ganz Works of Budapest and de Dion-Bouton of Paris collaborated to build a number of railcars for the Hungarian State Railways together with units with de Dion-Bouton boilers, Ganz steam motors and equipments, and Raba carriages built by the Raba Hungarian Wagon and Machine Factory in Győr. In 1908, the Borzsavölgyi Gazdasági Vasút (BGV), a narrow-gauge railway in Carpathian Ruthenia (today's Ukraine), purchased five railcars from Ganz and four railcars from the Hungarian Royal State Railway Machine Factory with de Dion-Bouton boilers. The Ganz company started to export steam motor railcars to the United Kingdom, Italy, Canada, Japan, Russia and Bulgaria.[18][19][20]

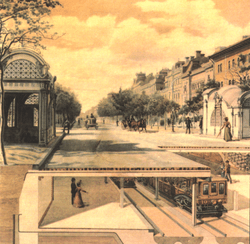

The Ganz Works identified the significance of induction motors and synchronous motors commissioned Kálmán Kandó (1869–1931) to develop it. In 1894, Hungarian engineer Kálmán Kandó developed high-voltage three-phase AC motors and generators for electric locomotives. The first-ever electric rail vehicle manufactured by Ganz Works was a 6 HP pit locomotive with direct current traction system. The first Ganz made asynchronous rail vehicles (altogether 2 pieces) were supplied in 1898 to Évian-les-Bains (Switzerland) with a 37 HP asynchronous traction system. The Ganz Works won the tender of electrification of railway of Valtellina Railways in Italy in 1897. Under the management and on the base of plans of Kálmán Kandó, three phase electric traction (two upper wires + rails) of feed 3 kV and 15 Hz – produced by a different power station – was realized for thirty years from 1902. Italian railways were the first in the world to introduce electric traction for the entire length of a main line rather than just a short stretch. The 106 km Valtellina line was opened on 4 September 1902, designed by Kandó and a team from the Ganz works.[21][22] The electrical system was three-phase at 3 kV 15 Hz. The voltage was significantly higher than used earlier and it required new designs for electric motors and switching devices.[23][24] The three-phase two-wire system was used on several railways in Northern Italy and became known as "the Italian system". Kandó was invited in 1905 to undertake the management of Società Italiana Westinghouse and led the development of several Italian electric locomotives.[23] In 1918,[25] Kandó invented and developed the rotary phase converter, enabling electric locomotives to use three-phase motors whilst supplied via a single overhead wire, carrying the simple industrial frequency (50 Hz) single phase AC of the high voltage national networks.[22]

Rail rolling stock

After World War I, in the frames of the Ganz Works, Kálmán Kandó constructed one-phase railway electric system of 16 kV and 50 Hz incipient all over the world. Its main attribute was the feed by normal network, so additional power station became unnecessary. Consequently, Hungarian electric traction could be formed according to the country's energy management. Kálmán Kandó adapted the speed-torque curve to electric traction through changing the phase number and pole number. Kálmán Kandó incorporated a phase shifter in the locomotives which governed speed levels.

Because of early death of Kálmán Kandó, László Verebély continued the work for the Hungarian Railways (MÁV). Moreover, he managed the construction of a nationwide power station (Bánhida) supplying as the railways as Budapest with electric power by transmission line of 110 kV. He elaborated the first plans of the nationwide cooperation of electric energy. In the 1930s he organized the Department of Electric Stations and Railways of the BMGE, so he became a professor of a significant branch of heavy current engineering.[26]

In 1959 Ganz merged with the MÁVAG company and was renamed Ganz-MÁVAG.

In 1976 Ganz-Mávag supplied ten 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge 3-car diesel trainset to the Hellenic Railways Organisation (OSE), designated as Class AA-91 and four 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in) metre gauge 4-car trainsets, designated as Class A-6451. In 1981/82 Ganz-Mávag supplied to OSE 11 B-B diesel-hydraulic DHM7-9 locomotives, designated as class A-251. Finally, in 1983, OSE bought eleven 3-car metric gauge trainsets, designated as Class A-6461. All these locomotives and trainsets have been withdrawn with the exception of one standard and one metric gauge trainset.

In 1982/83 Ganz-Mávag supplied an order for electric multiple units to New Zealand Railways Corporation for Wellington suburban services. The order was made in 1979, and was for 44 powered units and 44 trailer units, see New Zealand EM class electric multiple unit.

Shipbuilding

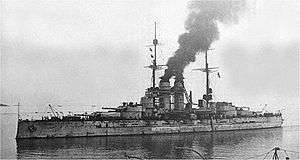

In 1911, The Ganz Company merged with the Danubius shipbuilding company, which largest shipbuilding company in Hungary. Since 1911, the unified company adopted the "Ganz–Danubius" brand name. As Ganz Danubius, the company became involved in shipbuilding before, and during, World War I. Ganz was responsible for building the dreadnought Szent István, all of the Novara-class cruisers, and built diesel-electric U-boats at its shipyard in Budapest, for final assembly at Fiume. Several U-Boats of the U-XXIX class, U-XXX class, U-XXXI class and U-XXXII class were completed,[27] and a number of other types were laid down, remaining incomplete at the war's end.[28] By the end of the First World War, 116 naval vessels were built by The Ganz-Danubius company. The company built some ocean liners too.

SM U-29 Submarine of the Austro-Hungarian Navy, built by the Ganz-Danubius company

SM U-29 Submarine of the Austro-Hungarian Navy, built by the Ganz-Danubius company The back of SM U-31 submarine during its assembly in the Ganz–Danubius Company on 24 April 1916

The back of SM U-31 submarine during its assembly in the Ganz–Danubius Company on 24 April 1916 The battle damaged SMS Novara (1913) after a victorious naval battle

The battle damaged SMS Novara (1913) after a victorious naval battle

Aircraft

The first Hungarian "aeroplane factory" was founded by Ganz Company and Weiss Manfréd Works in 1912. During World War I, the company made many types of Albatros and Fokker fighter planes.

The world's first turboprop jet was the Jendrassik Cs-1 designed by the Hungarian mechanical engineer György Jendrassik. It was built and tested in the Ganz factory in Budapest between 1939 and 1942. It was planned to fit to the Varga RMI-1 X/H twin-engined reconnaissance bomber designed by László Varga in 1940, but the program was cancelled. Jendrassik had also designed a small-scale 75 kW turboprop in 1937.

Trams

Ganz-MÁVAG delivered 29 trams (2 car sets) to Alexandria, Egypt from 1985 to 1986.[29]

After World War II

In 1947, the Ganz Works were nationalised and in 1949 they became independent and six big companies came into existence, e.g. the Ganz Transformer Factory. In 1959, Ganz Wagon and Machine Factory merged with the MÁVAG Locomotive and Machine Factory under the name of Ganz-MÁVAG Locomotive, Wagon and Machine Works. Of the products of the Works, outstanding results were born in the field of the manufacture of diesel motor-railcars and motor trains. Traditional products included tramcars as well, with which, first of all, the tramway network of Budapest was provided by the Works. In the meantime the Foundry workshop was closed down.

In 1974, the locomotive and wagon Works were merged under the name of Railway Vehicle Factory and then the machine construction branch of went through significant developments. The production of industrial and apartment house lifts became a new branch. Ganz-MÁVAG took over a lot of smaller plants in the 1960s and 1970s and their product range was extended. Besides others, they increased their bridge-building capacity; they made iron structures for several Tisza Bridges, for the Erzsébet Bridge in Budapest, for public road bridges in Yugoslavia and for several industrial halls.

The Ganz Shipyard experienced its most stirring times during the four decades following nationalisation: in the course of this period 1100 ship units were produced, the number of the completed seagoing ships was 240 and that of floating cranes was 663. As a result of the great economic and social crises of the 1980s the Ganz-MÁVAG had to be reorganised. The company was transformed into seven independent Works and three joint ventures.

In 1989, the British company Telfos Holding gained a majority of the shares in Ganz Railway Vehicle Factory Co. Ltd. The name of the company was changed to Ganz-Hunslet Co. Ltd. In the course of 1991 and 1992, the Austrian company Jenbacher Werke obtained 100% of the company's shares and consequently the railway vehicle factory now is a member of the international railway vehicle manufacturing group, Jenbacher Transport Systeme. At present, the Ganz Electric Works, under the name of Ganz-Ansaldo is a member of the Italian industrial giant, Ansaldo. The Ganz Works were transformed into holdings. Ganz-Danubius was wound up in 1994. The Ganz Electric Meter Factory in Gödöllő became the member of the international Schlumberger group.

References

- ↑ Ganz is now CG Retrieved 2009-11-28.

- ↑ Ganz-Škoda Electric Ltd.

- ↑ Iván Boldizsár: NHQ; the New Hungarian Quarterly, Volume 16, Issue 2; Volume 16, Issues 59–60, p. 128

- ↑ Hungarian Technical Abstracts: Magyar Műszaki Lapszemle, Volumes 10–13, p. 41

- ↑ Iván T. Berend: Case Studies on Modern European Economy: Entrepreneurship, Inventions, and Institutions, p. 151

- ↑ "Ganz Energetika Limited" (PDF). p. 2. Retrieved 2011-06-06.

- ↑ Hirlapkiad́o Vállalat: The Hungarian Economy, Volumes 26–27, p. 34

- ↑ Ganz Works – the 19th century

- ↑ Palgrave Macmillan Ltd (2016). Dictionary of Physics. Springer. p. 569. ISBN 9781349660223.

- ↑ IEEE Power Engineering Society, IEEE Power Engineering Society. Winter Meeting: Discussions and closures of abstracted papers from the winter meeting, New York, New York, January 30 – February 4, 1977, p. XXIV.

- ↑ http://www.sze.hu/~mgergo/EnergiatudatosEpulettervezes/2013_1_feladat/ErosErika/V%EDzenergia%20hasznos%EDt%E1s%20szigetk%F6zi%20szemmel%20EL%D5AD%C1SANYAG.pdf

- ↑ American Society for Engineering Education (1995). Proceedings, Part 2. p. 1848.

- ↑ Robert L. Libbey (1991). A Handbook of Circuit Math for Technical Engineers. CRC Press. p. 22. ISBN 9780849374005.

- ↑ "Ottó Bláthy, Miksa Déri, Károly Zipernowsky". IEC Techline. Retrieved Apr 16, 2010.

- ↑ Hungarian Inventors and their Inventions

- ↑ Eugenii Katz. "Blathy". Clarkson University. Archived from the original on June 25, 2008. Retrieved 2009-08-04.

- ↑ http://www.omikk.bme.hu/archivum/angol/htm/blathy_o.htm

- ↑ Railroad Gazette - Volume 37 - Page 296 (printed in 1904)

- ↑ Modern Machinery - Volumes 19-20 - Page 206 (Printed in 1906)

- ↑ John Robertson Dunlap, Arthur Van Vlissingen, John Michael Carmody: Factory and Industrial Management - Volume 33 - Page 1003 (printed in 1907

- ↑ Duffy (2003), p. 120-121.

- 1 2 Hungarian Patent Office. "Kálmán Kandó (1869–1931)". www.mszh.hu. Retrieved 2008-08-10.

- 1 2 "Kalman Kando". Retrieved 2011-10-26.

- ↑ "Kalman Kando". Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- ↑ Michael C. Duffy (2003). Electric Railways 1880-1990. IET. p. 137. ISBN 9780852968055.

- ↑ http://energyhistory.energosolar.com/en_20th_century_electric_history.htm

- ↑ R.H. Gibson, Maurice Prendergast (2002). The German Submarine War 1914–1918. Periscope Publishing Ltd. p. 386. ISBN 9781904381082.

- ↑ http://www.gwpda.org/naval/ahsubs.htm Sieche article on KuK U-Boats

- ↑ https://tramways.files.wordpress.com/2014/11/fleet-list-egypt-2010.pdf

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ganz Works. |

- A photo of a Ganz railcar of Hungarian State Railways c1936

- A withdrawn Ganz-Mavag DMU at Mendoza, Argentina

- Ganz Transelektro Ltd's page in english

- Ganz Danubius homepage