Galveston, Texas

| Galveston, Texas | ||

|---|---|---|

| City | ||

| City of Galveston | ||

|

From upper left: Galveston skyline, Bishop's Palace, Ashbel Smith Building, Moody Gardens Aquarium, St. Mary Cathedral Basilica and Galveston Island Historic Pleasure Pier | ||

| ||

| Nickname(s): The Oleander City[1] | ||

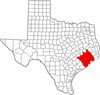

Location in Galveston County in the state of Texas | ||

| Coordinates: 29°16′52″N 94°49′33″W / 29.28111°N 94.82583°WCoordinates: 29°16′52″N 94°49′33″W / 29.28111°N 94.82583°W | ||

| Country |

| |

| State |

| |

| County | Galveston | |

| Incorporated | 1839 | |

| Government | ||

| • Type | Council–manager | |

| • Mayor | James D. Yarbrough | |

| • City Manager | Brian Maxwell | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 208.3 sq mi (539.6 km2) | |

| • Land | 46.1 sq mi (119.5 km2) | |

| • Water | 162.2 sq mi (420.1 km2) | |

| Elevation | 7 ft (2 m) | |

| Population (2010) | ||

| • Total | 47,743 | |

| • Density | 1,240/sq mi (478.9/km2) | |

| • Demonym | Galvestonian | |

| Time zone | CST (UTC-6) | |

| • Summer (DST) | CDT (UTC-5) | |

| ZIP codes | 77550-77555 | |

| Area code(s) | 409 | |

| FIPS code | 48-28068[2] | |

| GNIS feature ID | 1377745[3] | |

| Website | cityofgalveston.org | |

Galveston (/ˈɡælvᵻstən/ GAL-viss-tən) is a coastal city located on Galveston Island and Pelican Island in the U.S. state of Texas. The community of 208.3 square miles (539 km2), with its population of 47,762 people (2012 Census estimate), is the county seat and second-largest municipality of Galveston County. It is located within Houston–The Woodlands–Sugar Land metropolitan area.

Named after Bernardo de Gálvez y Madrid, Count of Gálvez (born in Macharaviaya, Spain), Galveston's first European settlements on the island were constructed around 1816 by French pirate Louis-Michel Aury to help the fledgling Republic of Mexico fight Spain. The Port of Galveston was established in 1825 by the Congress of Mexico following its successful independence from Spain. The city served as the main port for the Texas Navy during the Texas Revolution, and later served as the capital of the Republic of Texas.

During the 19th century, Galveston became a major U.S. commercial center and one of the largest ports in the United States. It was devastated by the 1900 Galveston Hurricane, whose effects included flooding and a storm surge. The natural disaster on the exposed barrier island is still ranked as the deadliest in United States history, with an estimated death toll of 6,000 to 12,000 people.

Much of Galveston's modern economy is centered in the tourism, health care, shipping, and financial industries. The 84-acre (340,000 m2) University of Texas Medical Branch campus with an enrollment of more than 2,500 students is a major economic force of the city. Galveston is home to six historic districts containing one of the largest and historically significant collections of 19th-century buildings in the United States, with over 60 structures listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

History

Exploration and 19th century development

Galveston Island was originally inhabited by members of the Karankawa and Akokisa tribes who called the island Auia. The Spanish explorer Cabeza de Vaca and his crew were shipwrecked on the island or nearby in November 1528,[4] calling it "Isla de Malhado" ("Isle of Bad Fate"). They began their years-long trek to a Spanish settlement in Mexico City.[5] During his charting of the Gulf Coast in 1785, the Spanish explorer José de Evia named the island Villa Gálvez or Gálveztown in honor of Bernardo de Gálvez y Madrid, Count of Gálvez.[5]

The first permanent European settlements on the island were constructed around 1816 by the pirate Louis-Michel Aury as a base of operations to support Mexico's rebellion against Spain.[6] In 1817, Aury returned from an unsuccessful raid against Spain to find Galveston occupied by the pirate Jean Lafitte.[6] Lafitte organized Galveston into a pirate "kingdom" he called "Campeche", anointing himself the island's "head of government."[7] Lafitte remained in Galveston until 1821, when he and his raiders were forced off the island by the United States Navy.[7][8]

In 1825 the Congress of Mexico established the Port of Galveston and in 1830 erected a customs house.[9] Galveston served as the capital of the Republic of Texas when in 1836 the interim president David G. Burnet relocated his government there.[9] In 1836, the French-Canadian Michel Branamour Menard and several associates purchased 4,605 acres (18.64 km2) of land for $50,000 to found the town that would become the modern city of Galveston.[10][11][12] As Anglo-Americans migrated to the city, they brought along or purchased enslaved African-Americans, some of whom worked domestically or on the waterfront, including on riverboats.

In 1839 the City of Galveston adopted a charter and was incorporated by the Congress of the Republic of Texas.[12][13] The city was by then a burgeoning port of entry and attracted many new residents in the 1840s and later among the flood of German immigrants to Texas, including Jewish merchants.[14] Together with ethnic Mexican residents, these groups tended to oppose slavery, support the Union during the Civil War, and join the Republican Party after the war.

During this expansion, the city had many "firsts" in the state, with the founding of institutions and adoption of inventions: post office (1836), naval base (1836), Texas chapter of a Masonic order (1840); cotton compress (1842), Catholic parochial school (Ursuline Academy) (1847), insurance company (1854), and gas lights (1856).[12][15]

During the American Civil War, Confederate forces under Major General John B. Magruder attacked and expelled occupying Union troops from the city in January 1863 in the Battle of Galveston.[16] In 1867 Galveston suffered a yellow fever epidemic; 1800 people died in the city.[17] These occurred in waterfront and river cities throughout the 19th century, as did cholera epidemics.

The city's progress continued through the Reconstruction era with numerous "firsts": construction of the opera house (1870), and orphanage (1876), and installation of telephone lines (1878) and electric lights (1883).[12][15][18][19] Having attracted freedmen from rural areas, in 1870 the city had a black population that totaled 3,000,[20] made up mostly of former slaves but also by numerous persons who were free men of color and educated before the war. The "blacks" comprised nearly 25% of the city's population of 13,818 that year.[21]

During the post-Civil-War period, leaders such as George T. Ruby and Norris Wright Cuney, who headed the Texas Republican Party and promoted civil rights for freedmen, helped to dramatically improve educational and employment opportunities for blacks in Galveston and in Texas.[22][23] Cuney established his own business of stevedores and a union of black dockworkers to break the white monopoly on dock jobs. Galveston was a cosmopolitan city and one of the more successful during Reconstruction; the Freedmen's Bureau was headquartered here. German families sheltered teachers from the North, and hundreds of freedmen were taught to read. Its business community promoted progress, and immigrants continued to stay after arriving at this port of entry.[24]

By the end of the 19th century, the city of Galveston had a population of 37,000. Its position on the natural harbor of Galveston Bay along the Gulf of Mexico made it the center of trade in Texas. It was one of the largest cotton ports in the nation, in competition with New Orleans.[25] Throughout the 19th century, the port city of Galveston grew rapidly and the Strand was considered the region's primary business center. For a time, the Strand was known as the "Wall Street of the South".[26] In the late 1890s, the government constructed Fort Crockett defenses and coastal artillery batteries in Galveston and along the Bolivar Roads. In February 1897, Galveston was officially visited by the USS Texas (nicknamed Old Hoodoo), the first commissioned battleship of the United States Navy. During the festivities, the ship's officers were presented with a $5,000 silver service, adorned with various Texas motifs, as a gift from the citizens of the state.

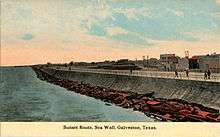

Hurricane of 1900 and recovery

On September 8, 1900, the island was struck by a devastating hurricane.[27] This event holds the record as the United States' deadliest natural disaster.[27][28] The city was devastated, and an estimated 6,000 to 8,000 people on the island were killed.[27] Following the storm, a 10-mile (16 km) long, 17 foot (5.2 m) high seawall was constructed to protect the city from floods and hurricane storm surge. A team of engineers including Henry Martyn Robert (Robert's Rules of Order) designed the plan to raise much of the existing city to a sufficient elevation behind a seawall so that confidence in the city could be maintained.

The city developed the city commission form of city government, known as the "Galveston Plan", to help expedite recovery.[29]

Despite attempts to draw new investment to the city after the hurricane, Galveston never fully returned to its previous levels of national importance or prosperity. Development was also hindered by the construction of the Houston Ship Channel, which brought the Port of Houston into direct competition with the natural harbor of the Port of Galveston for sea traffic. To further her recovery, and rebuild her population, Galveston actively solicited immigration. Through the efforts of Rabbi Henry Cohen and Congregation B'nai Israel, Galveston became the focus of an immigration plan called the Galveston Movement that, between 1907 and 1914, diverted roughly 10,000 Eastern European Jewish immigrants from the usual destinations of the crowded cities of the Northeastern United States.[30] Additionally numerous other immigrant groups, including Greeks, Italians and Russian Jews, came to the city during this period.[31] This immigration trend substantially altered the ethnic makeup of the island, as well as many other areas of Texas and the western U.S.

Though the storm stalled economic development and the city of Houston developed as the region's principal metropolis, Galveston economic leaders recognized the need to diversify from the traditional port-related industries. In 1905 William Lewis Moody, Jr. and Isaac H. Kempner, members of two of Galveston's leading families, founded the American National Insurance Company.[32] Two years later, Moody established the City National Bank, which would later become the Moody National Bank.[33][34]

During the 1920s and 1930s, the city re-emerged as a major tourist destination.[35][36] Under the influence of Sam Maceo and Rosario Maceo, the city exploited the prohibition of liquor and gambling in clubs like the Balinese Room, which offered entertainment to wealthy Houstonians and other out-of-towners. Combined with prostitution, which had existed in the city since the Civil War, Galveston became known as the "sin city" of the Gulf.[37] Galvestonians accepted and supported the illegal activities, often referring to their island as the "Free State of Galveston".[38][39] The island had entered what would later become known as the "open era".[40]

The 1930s and 1940s brought much change to the Island City. During World War II, the Galveston Municipal Airport, predecessor to Scholes International Airport, was re-designated a U.S. Army Air Corps base and named "Galveston Army Air Field". In January 1943, Galveston Army Air Field was officially activated with the 46th Bombardment Group serving an anti-submarine role in the Gulf of Mexico. In 1942, William Lewis Moody, Jr., along with his wife Libbie Shearn Rice Moody, established the Moody Foundation, to benefit "present and future generations of Texans." The foundation, one of the largest in the United States, would play a prominent role in Galveston during later decades, helping to fund numerous civic and health-oriented programs.[41]

Post–World War II

The end of the war drastically reduced military investment in the island. Increasing enforcement of gambling laws and the growth of Las Vegas, Nevada as a competitive center of gambling and entertainment put pressure on the gaming industry on the island.[42] Finally in 1957, Texas Attorney General Will Wilson and the Texas Rangers began a massive campaign of raids which disrupted gambling and prostitution in the city.[43] As these vice industries crashed, so did tourism, taking the rest of the Galveston economy with it.[44] Neither the economy nor the culture of the city was the same afterward.[45]

.jpg)

The economy of the island entered a long stagnant period. Many businesses relocated off the island during this period; however, health care, insurance and financial industries continue to be strong contributors to the economy. By 1959, the city of Houston had long out-paced Galveston in population and economic growth. Beginning in 1957, the Galveston Historical Foundation began its efforts to preserve historic buildings.[46] The 1966 book The Galveston That Was helped encourage the preservation movement. Restoration efforts financed by motivated investors, notably Houston businessman George P. Mitchell, gradually developed the Strand Historic District and reinvented other areas. A new, family-oriented tourism emerged in the city over many years.

With the 1960s came the expansion of higher education in Galveston. Already home to the University of Texas Medical Branch, the city got a boost in 1962 with the creation of the Texas Maritime Academy, predecessor of Texas A&M University at Galveston; and by 1967 a community college, Galveston College, had been established.[47]

In the 2000s, property values rose after expensive projects were completed [48] and demand for second homes by the wealthy increased. It has made it difficult for middle-class workers to find affordable housing on the island.[49]

Hurricane Ike made landfall on Galveston Island in the early morning of September 13, 2008 as a Category 2 hurricane with winds of 110 miles per hour. Damage was extensive to buildings along the seawall.[50]

After the storm, the island was rebuilt with further investments into tourism, shipping, and continued emphasis on higher education and health care. Notably the addition of the Galveston Island Historic Pleasure Pier and the replacement of the bascule-type drawbridge on the railroad causeway with a vertical-lift-type drawbridge to allow heavier freight.[51][52]

Geography

The city of Galveston is situated on Galveston Island, a barrier island off the Texas Gulf coast near the mainland coast. Made up of mostly sand-sized particles and smaller amounts of finer mud sediments and larger gravel-sized sediments, the island is unstable, affected by water and weather, and can shift its boundaries through erosion.

The city is about 45 miles (72 km) southeast of downtown Houston.[53] The island is oriented generally northeast-southwest, with the Gulf of Mexico on the east and south, West Bay on the west, and Galveston Bay on the north. The island's main access point from the mainland is the Interstate Highway 45 causeway that crosses West Bay on the northeast side of the island.

A deepwater channel connects Galveston's harbor with the Gulf and the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 208.4 square miles (540 km2), of which 46.2 square miles (120 km2) is land and 162.2 square miles (420 km2) and 77.85% is water. The island is 50 miles (80 km) southeast of Houston.[54]

The western portion of Galveston is referred to as the "West End". Communities in eastern Galveston include Lake Madeline, Offats Bayou, Central City, Fort Crockett, Bayou Shore, Lasker Park, Carver Park, Kempner Park, Old City/Central Business District, San Jacinto, East End, and Lindale.[55] As of 2009 many residents of the west end use golf carts as transportation to take them to and from residential houses, the Galveston Island Country Club, and stores. In 2009, Chief of Police Charles Wiley said he believed that golf carts should be prohibited outside golf courses, and West End residents campaigned against any ban on their use.[56]

In 2011 Rice University released a study, "Atlas of Sustainable Strategies for Galveston Island," which argued that the West End of Galveston was quickly eroding and that the City should reduce construction and/or population in that area. It recommended against any rebuilding of the West End in the event of damage due to another hurricane.[57]

Historic districts

Galveston is home to six historic districts with over 60 structures listed representing architectural significance in the National Register of Historic Places.[58] The Silk Stocking National Historic District, located between Broadway and Seawall Boulevard and bounded by Ave. K, 23rd St., Ave. P, and 26th St., contains a collection of historic homes constructed from the Civil War through World War II.[59] The East End Historic District, located on both sides of Broadway and Market Streets, contains 463 buildings. Other historic districts include Cedar Lawn, Denver Court and Fort Travis.[58]

The Strand National Historic Landmark District is a National Historic Landmark District of mainly Victorian era buildings that have been adapted for use as restaurants, antique stores, historical exhibits, museums and art galleries. The area is a major tourist attraction for the island city. It is the center for two very popular seasonal festivals. It is widely considered the island's shopping and entertainment center. Today, "the Strand" is generally used to refer to the entire five-block business district between 20th and 25th streets in downtown Galveston, very close to the city's wharf.

Climate

| Galveston | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Galveston's climate is classified as humid subtropical (Cfa in Köppen climate classification system).[60] Prevailing winds from the south and southeast bring both heat from the deserts of Mexico and moisture from the Gulf of Mexico.[61] Summer temperatures regularly exceed 90 °F (32 °C) and the area's humidity drives the heat index even higher, while nighttime lows average around 80 °F (27 °C).[62][63][64] Winters in the area are temperate with typical January highs above 60 °F (16 °C) and lows near 50 °F (10 °C). Snowfall is generally rare; however, 15.4 in (39.1 cm) of snow fell in February 1895, making the 1894–95 winter the snowiest on record. Annual rainfall averages well over 40 inches (1,000 mm) a year with some areas typically receiving over 50 inches (1,300 mm).[65][66]

Hurricanes are an ever-present threat during the summer and fall season, which puts Galveston in Coastal Windstorm Area. Galveston Island and the Bolivar Peninsula are generally at the greatest risk among the communities near the Galveston Bay. However, though the island and peninsula provide some shielding, the bay shoreline still faces significant danger from storm surge.[67][68][69]

| Climate data for Galveston, Texas (Scholes Int'l), 1981−2010 normals, extremes 1871−present[70] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 78 (26) |

83 (28) |

87 (31) |

95 (35) |

94 (34) |

100 (38) |

101 (38) |

100 (38) |

104 (40) |

94 (34) |

85 (29) |

80 (27) |

104 (40) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 61.8 (16.6) |

64.3 (17.9) |

70.2 (21.2) |

75.9 (24.4) |

83.0 (28.3) |

88.2 (31.2) |

89.6 (32) |

90.3 (32.4) |

87.4 (30.8) |

80.6 (27) |

71.6 (22) |

63.9 (17.7) |

77.2 (25.1) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 48.6 (9.2) |

50.9 (10.5) |

56.6 (13.7) |

64.4 (18) |

72.3 (22.4) |

77.5 (25.3) |

79.4 (26.3) |

79.7 (26.5) |

75.9 (24.4) |

68.1 (20.1) |

58.6 (14.8) |

50.7 (10.4) |

65.2 (18.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 11 (−12) |

8 (−13) |

26 (−3) |

38 (3) |

50 (10) |

57 (14) |

66 (19) |

67 (19) |

52 (11) |

39 (4) |

26 (−3) |

14 (−10) |

8 (−13) |

| Average rainfall inches (mm) | 4.20 (106.7) |

2.57 (65.3) |

3.16 (80.3) |

3.05 (77.5) |

4.32 (109.7) |

5.69 (144.5) |

3.80 (96.5) |

4.39 (111.5) |

6.03 (153.2) |

5.52 (140.2) |

4.51 (114.6) |

3.52 (89.4) |

50.76 (1,289.4) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 145.0 | 163.4 | 209.0 | 225.5 | 265.7 | 298.5 | 309.0 | 280.4 | 237.9 | 237.2 | 176.9 | 150.5 | 2,699 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 44 | 52 | 56 | 58 | 63 | 71 | 72 | 69 | 64 | 67 | 55 | 47 | 61 |

| Source #1: NOAA (sun 1961–1990)[71][72] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: The Weather Channel[73] The Washington Post (June record high)[74] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Galveston, Texas (COOP station), 1981−2010 normals | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 83 (28) |

83 (28) |

86 (30) |

92 (33) |

94 (34) |

99 (37) |

101 (38) |

103 (39) |

100 (38) |

94 (34) |

88 (31) |

84 (29) |

103 (39) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 61.0 (16.1) |

63.1 (17.3) |

68.6 (20.3) |

74.7 (23.7) |

81.7 (27.6) |

87.1 (30.6) |

89.2 (31.8) |

89.8 (32.1) |

86.5 (30.3) |

79.7 (26.5) |

71.3 (21.8) |

64.1 (17.8) |

76.4 (24.7) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 45.1 (7.3) |

47.3 (8.5) |

54.1 (12.3) |

62.0 (16.7) |

70.6 (21.4) |

76.1 (24.5) |

77.9 (25.5) |

77.8 (25.4) |

73.3 (22.9) |

66.1 (18.9) |

56.5 (13.6) |

47.3 (8.5) |

62.8 (17.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 11 (−12) |

8 (−13) |

26 (−3) |

37 (3) |

52 (11) |

57 (14) |

67 (19) |

51 (11) |

52 (11) |

39 (4) |

29 (−2) |

14 (−10) |

8 (−13) |

| Average rainfall inches (mm) | 3.69 (93.7) |

2.99 (75.9) |

2.85 (72.4) |

2.19 (55.6) |

3.01 (76.5) |

4.83 (122.7) |

3.85 (97.8) |

3.35 (85.1) |

5.36 (136.1) |

4.15 (105.4) |

3.42 (86.9) |

3.36 (85.3) |

43.05 (1,093.5) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.8 | 8.5 | 6.9 | 5.0 | 6.1 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 6.9 | 8.0 | 7.1 | 8.2 | 8.2 | 90.1 |

| Source: NOAA[71][75] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

2000 Census data

As of the census[2] of 2000, there were 57,247 people, 23,842 households, and 13,732 families residing in the city. As of the 2006 U.S. Census estimate, the city had a total population of 57,466.[76] The population density was 1,240.4 people per square mile (478.9/km2). There were 30,017 housing units at an average density of 650.4 per square mile (251.1/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 58.7% White, 25.5% Black or African American, 0.4% Native American, 3.2% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 9.7% from other races, and 2.4% from two or more races. 25.8% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race. There were 23,842 households out of which 26.3% had children under the age of 13 living with them, 36.6% were married couples living together, 16.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 42.4% were non-families. 35.6% of all households were made up of individuals and 11.2% had someone living alone who was 89 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.30 and the average family size was 3.03.

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 4,177 | — | |

| 1860 | 7,307 | 74.9% | |

| 1870 | 13,818 | 89.1% | |

| 1880 | 22,248 | 61.0% | |

| 1890 | 29,084 | 30.7% | |

| 1900 | 37,789 | 29.9% | |

| 1910 | 36,981 | −2.1% | |

| 1920 | 44,255 | 19.7% | |

| 1930 | 52,938 | 19.6% | |

| 1940 | 60,862 | 15.0% | |

| 1950 | 66,568 | 9.4% | |

| 1960 | 67,175 | 0.9% | |

| 1970 | 61,809 | −8.0% | |

| 1980 | 61,902 | 0.2% | |

| 1990 | 59,070 | −4.6% | |

| 2000 | 57,247 | −3.1% | |

| 2010 | 47,743 | −16.6% | |

| Est. 2015 | 50,180 | [77] | 5.1% |

In the city the population was 23.4% under the age of 13, 11.3% from 13 to 24, 29.8% from 25 to 44, 21.8% from 45 to 88, and 13.7% who were 89 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females there were 93.4 males. For every 100 females age 13 and over, there were 90.4 males. The median income for a household in the city was $28,895, and the median income for a family was $35,049. Males had a median income of $30,150 versus $26,030 for females. The per capita income for the city was $18,275. About 17.8% of families and 22.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 32.1% of those under age 13 and 14.2% of those age 89 or over.

Economy

Port of Galveston

The Port of Galveston, also called Galveston Wharves, began as a trading post in 1825.[79] Today, the port has grown to 850 acres (3.4 km2) of port facilities. The port is located on the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway, on the north side of Galveston Island, with some facilities on Pelican Island. The port has facilities to handle all types of cargo including containers, dry and liquid bulk, breakbulk, Roll-on/roll-off, refrigerated cargo and project cargoes.

The port also serves as a passenger cruise ship terminal for cruise ships operating in the Caribbean. The terminal was home port to two Carnival Cruise Lines vessels, the Carnival Conquest and the Carnival Ecstasy. In November 2011 the company made Galveston home port to its 3,960-passenger mega-ships Carnival Magic and Carnival Triumph, as well. Carnival Magic sails a seven-day Caribbean cruise from Galveston, and it is the largest cruise ship based at the Port year-round.[80][81] Galveston is the home port to Royal Caribbean International's, MS Liberty of the Seas, which is the largest cruise ship ever based here and one of the largest ships in the world. In September 2012 Disney Cruise Line's Disney Magic also became based in Galveston, offering four-, six-, seven-, and eight-day cruises to the Caribbean and the Bahamas.

Finance

American National Insurance Company, one of the largest life insurance companies in the United States, is based in Galveston. The company and its subsidiaries operate in all 50 U.S. states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and American Samoa. Through its subsidiary, American National de México, Compañía de Seguros de Vida, it provides products and services in Mexico.[82][83] Moody National Bank, with headquarters in downtown Galveston, is one of the largest privately owned Texas-based banks. Its trust department, established in 1927, administers over 12 billion dollars in assets, one of the largest in the state.[84] In addition, the regional headquarters of Iowa-based United Fire & Casualty Company are located in the city.[85]

Healthcare

Galveston is the home of several of the largest teaching hospitals in the state, located on the campus of the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. Prior to Hurricane Ike, the University employed more than 12,000 people. Its significant growth in the 1970s and 1980s was attributable to a uniquely qualified management and medical faculty including: Mr. John Thompson; Dr. William James McGanity, Dr. William Levin, Dr. David Daeschner and many more.

Ike severely damaged the 550-bed John Sealy Hospital causing the University of Texas System Board of Regents to cut nearly one-third of the hospital staff. Since the storm, the regents have committed to spending $713 million to restore the campus, construct new medical towers, and return John Sealy Hospital to its 550-bed pre-storm capacity.[86]

In 2011, the UT Board of Regents approved the construction of a new 13 story hospital that will be located next to John Sealy Hospital. Construction will begin in the fall of 2011, with the demolition of the old Jennie Sealy and Shriners hospitals, and continue until completion in 2016. The facility will have 250 room, 20 operating suites and 54 intensive care beds. When the new hospital is complete, along with the renovations at John Sealy, both complexes will have around 600 beds.[87]

The university reopened their Level I Trauma Center on August 1, 2009 which had been closed for eleven months after the hurricane and, as of September 2009, had reopened 370 hospital beds.[86][88]

The city is also home to a 30-bed acute burns hospital for children, the Shriners Burns Hospital at Galveston.[89] The Galveston hospital is one of only four in the chain of 22 non-profit Shriners hospitals, that provides acute burns care.[90] Although the Galveston Hospital was damaged by Hurricane Ike, the Shriners national convention held in July 2009 voted to repair and reopen the hospital.[89][91]

Tourism

In the late 1800s Galveston was known as the "Playground of the South"[92][93] Today, it still retains a shared claim to the title among major cities along the Gulf Coast states. Galveston is a popular tourist destination which in 2007 brought $808 million to the local economy and attracted 5.4 million visitors. The city features an array of lodging options, including hotels such as the historic Hotel Galvez and Tremont House, vintage bed and breakfast inns, beachfront condominiums, and resort rentals. The city's tourist attractions include the Galveston Island Historic Pleasure Pier, Galveston Schlitterbahn waterpark, Moody Gardens botanical park, the Ocean Star Offshore Drilling Rig & Museum, the Lone Star Flight Museum, Galveston Railroad Museum, a downtown neighborhood of historic buildings known as The Strand, many historical museums and mansions, and miles of beach front from the East End's Porretto Beach, Stewart Beach to the West End pocket parks.

The Strand plays host to a yearly Mardi Gras festival, Galveston Island Jazz & Blues Festival and a Victorian-themed Christmas festival called Dickens on the Strand (honoring the works of novelist Charles Dickens, especially A Christmas Carol) in early December. Galveston is home to several historic ships: the tall ship Elissa (the official Tall Ship of Texas) at the Texas Seaport Museum and USS Cavalla and USS Stewart, both berthed at Seawolf Park on nearby Pelican Island. Galveston is ranked the number one cruise port on the Gulf Coast and fourth in the United States.[94]

Arts and culture

Galveston Arts Center

Incorporated in 1986, Galveston Arts Center (GAC) is a non-profit, non-collecting arts organization. The center exhibits contemporary art, often by Texas-based artists, and offers educational and outreach programs. Notably, GAC organizes and produces Galveston ArtWalk. Museum entry is free to the public, although cash donations are welcomed. Tiered membership options and a range of volunteer opportunities are also available.[95]

In October 2015, Galveston Arts Center will celebrate relocation to its original home, the historic 1878 First National Bank Building on the Strand. This Italianate-style 1900 Storm survivor was extensively damaged during Hurricane Ike in 2008. Fortunately, just weeks before Ike made landfall, scaffolding was installed to support the entire structural load of the building for repairs, likely preventing collapse under heavy winds and storm surge. After a lengthy fundraising campaign, restoration is nearing completion.[96]

Galveston ArtWalk

ArtWalk takes place approximately every six weeks on Saturday evenings throughout the year. ArtWalk is organized by Galveston Arts Center, which releases an ArtWalk brochure featuring a map of participating venues as well as descriptions of shows and exhibits. Venues include GAC, Galveston Artist Residency and artist’s studios and galleries. Additionally, art is shown in “other walls”—for example MOD Coffeehouse or Mosquito Cafe—or outdoors at Art Market on Market Street. Musicians perform outdoors and at venues such as the Proletariat Gallery & Public House or Old Quarter Acoustic Cafe. While most ArtWalk events are concentrated downtown, there are a number or participants elsewhere on the island.[97]

Music and Performing Arts

Galveston Symphony Orchestra

Galveston is home to the Galveston Symphony Orchestra, an ensemble of amateur and professional musicians formed in 1979 under the direction of Richard W. Pickar, Musical Director-Conductor.[98]

Galveston Ballet

The Galveston Ballet is a regional pre-professional ballet company and academy serving Galveston county.[99] The company presents one full-length classical ballet in the spring of each year and one mixed repertory program in the fall, both presented at the Grand 1894 Opera House.

Artist Residency & Artist Housing

Galveston Artist Residency

Galveston Artist Residency (GAR) grants studio space, living space and a stipend to three visual artists each year. Resident artists work in a variety of mediums and exhibit their work in the GAR Gallery and Courtyards. Located in renovated industrial structures on the west side of downtown, GAR also hosts performances and other public events.[100]

The National Hotel Artist Lofts

The National Hotel Artist Lofts (NHAL) is an Artspace-developed property featuring twenty-seven live/work units designated as affordable housing for artists.[101] The project brought new life to the historic E.S. Levy Building, which was left abandoned for twenty years. Originally built as the Tremont Opera House in 1870, the structure was extensively renovated to serve various functions, from offices and stores to the National Hotel. The building also housed the U.S. National Weather Bureau's Galveston office under Isaac Cline during the 1900 Storm.[102]

Under Property Manager/Creative Director Becky Major, the unused retail space in the front of the building found a new purpose as a DIY art and music venue, despite its gutted and undeveloped state. In May 2015, the newly renovated space reopened as the Proletariat Gallery & Public House. This unique bar and gallery provides a common area for NHAL and neighborhood residents and a cultural hub for the broader community. Visual art, events and live music are regularly hosted in the space.[103]

Architecture

.jpg)

Galveston contains one of the largest and historically significant collections of 19th-century buildings in the United States. Galveston's architectural preservation and revitalization efforts over several decades have earned national recognition.[104][105]

Located in the Strand District, the Grand 1894 Opera House is a restored historic Romanesque Revival style Opera House that is currently operated as a not-for-profit performing arts theater.[106] The Bishop's Palace, also known as Gresham's Castle, is an ornate Victorian house located on Broadway and 14th Street in the East End Historic District of Galveston, Texas. The American Institute of Architects listed Bishop's Palace as one of the 100 most significant buildings in the United States, and the Library of Congress has classified it as one of the fourteen most representative Victorian structures in the nation.[107] The Galvez Hotel is a historic hotel that opened in 1911.[108] The building was named the Galvez, honoring Bernardo de Gálvez y Madrid, Count of Gálvez, for whom the city was named. The hotel was added to the National Register of Historic Places on April 4, 1979. The Michel B. Menard House, built in 1838 and oldest in Galveston, is designed in the Greek revival style. In 1880, the house was bought by Edwin N. Ketchum who was police chief of the city during the 1900 Storm. The Ketchum family owned the home until the 1970s. The red-brick Victorian Italianate home, Ashton Villa, was constructed in 1859 by James Moreau Brown. One of the first brick structures in Texas, it is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is a recorded Texas Historic Landmark. The structure is also the site of what was to become the holiday known as Juneteenth. Where On June 19, 1865, Union General Gordon Granger, standing on its balcony, read the contents of “General Order No. 3”, thereby emancipating all slaves in the state of Texas. [109][110][111] St. Joseph’s Church was built by German immigrants in 1859–60 and is the oldest wooden church building in Galveston and the oldest German Catholic Church in Texas.[112] The church was dedicated in April 1860, to St. Joseph, the patron saint of laborers. The building is a wooden gothic revival structure, rectangular with a square bell tower with trefoil window. The U.S. Custom House began construction in 1860 and was completed in 1861. The Confederate Army occupied the building during the American Civil War, In 1865, the Custom House was the site of the ceremony officially ending the Civil War.[113][114]

Galveston's modern architecture include the American National Insurance Company Tower (One Moody Plaza), San Luis Resort South and North Towers, The Breakers Condominiums, The Galvestonian Resort and Condos, One Shearn Moody Plaza, US National Bank Building, the Rainforest Pyramid at Moody Gardens, John Sealy Hospital Towers at UTMB and Medical Arts Building (also known as Two Moody Plaza).

Media

The Galveston County Daily News, founded in 1842, is the city's primary newspaper and the oldest continuously printed newspaper in Texas.[115] It currently serves as the newspaper of record for the city and the Texas City Post serves as the newspaper of record for the County. Radio station KGBC, on air from 1947–2010, has previously served as a local media outlet.[116] Television station KHOU signed on the air as KGUL-TV on March 23, 1953. Originally licensed in Galveston, KGUL was the second television station to launch in the Houston area after KPRC-TV.[117] One of the original investors in the station was actor James Stewart, along with a small group of other Galveston investors.[117] In June 1959, KGUL changed its call sign to KHOU and moved their main office to Houston. The local hip hop name for Galveston is "G-town."[118]

Sculpture

Many statues and sculptures can be found around the city. Here are a few well-known sculptures.

- 1900 Storm Memorial by David W. Moore

- Birth by Arthur Williams

- Dignified Resignation by Louis Amateis

- Dolphins by David W. Moore

- High Tide by Charles Parks

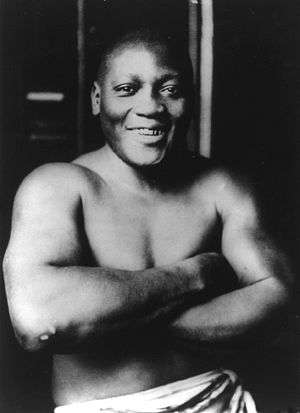

- Jack Johnson by Adrienne Isom

- Pink Dolphin Monument by Joe Joe Orangias

- Texas Heroes Monument by Louis Amateis

Notable people

Galveston has been home to many important figures in Texas and U.S. history. During the island's earliest history it became the domain of Jean Lafitte, the famed pirate and American hero of the War of 1812.[7] Richard Bache, Jr. who represented Galveston in the Senate of the Second Texas Legislature in 1847 and assisted in drawing up the Constitution of 1845. He was also the grandson of Benjamin Franklin, one of the Founding Fathers of the United States of America and Deborah Read. In 1886, the African-American Galveston civil rights leader Norris Wright Cuney rose to become the head of the Texas Republican Party and one of the most important Southern black leaders of the century.[119] Noted portrait and landscape artist Verner Moore White moved from Galveston the day before the 1900 hurricane. While he survived, his studio and much of his portfolio were destroyed.[120] A survivor of the hurricane was the Hollywood director King Vidor, who made his directing debut in 1913 with the film Hurricane in Galveston.[121] Later Jack Johnson, nicknamed the “Galveston Giant”, became the first black world heavyweight boxing champion.[122]

During the first half of the 20th century, William L. Moody Jr. established a business empire, which includes American National Insurance Company, a major national insurer, and founded the Moody Foundation, one of the largest charitable organizations in the United States.[123] Sam Maceo, a nationally known organized crime boss, with the help of his family, was largely responsible for making Galveston a major U.S. tourist destination from the 1920s to the 1940s.[37] John H. Murphy, a Texas newspaperman for seventy-four years, was the longtime executive vice president of the Texas Daily Newspaper Association. Douglas Corrigan became one of the early transatlantic aviators, and was given the nickname "Wrong Way" for claiming to have mistakenly made the ocean crossing after being refused permission to make the flight.[124] Grammy-award winning singer-songwriter Barry White was born on the island and later moved to Los Angeles.

George P. Mitchell, pioneer of hydraulic fracturing technology and developer of The Woodlands, Texas, was born and raised in Galveston.

More recently Tilman J. Fertitta, part of the Maceo bloodline, established the Landry's Restaurants corporation, which owns numerous restaurants and entertainment venues in Texas and Nevada.[125] Kay Bailey Hutchison was the senior senator from Texas and the first female Texas senator.[126]

Gilbert Pena, incoming 2015 Republican member of the Texas House of Representatives from Pasadena, was born in Galveston in 1949 and lived there in early childhood.[127]

Jonathan Pollard, who spied for Israel and was convicted in the US and sentenced to life in jail, was born in Galveston.[128] The film and television actor Lee Patterson, a native of Vancouver, British Columbia, lived in Galveston and died there in 2007.

Other notable people include Matt Carpenter, second baseman for the St. Louis Cardinals,[129] Mike Evans, wide receiver for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, actress Katherine Helmond and Tina Knowles, fashion designer and creator of House of Deréon, mother of Beyoncé and Solange. Grammy award winning R&B and Jazz legend Esther Phillips was born in Galveston in 1935.

Government and infrastructure

Local government

After the hurricane of 1900, the city originated the City Commission form of city government (which became known as the "Galveston Plan"). The city has since adopted the council-manager form of government. Galveston's city council serves as the city's legislative branch, while the city manager works as the chief executive officer, and the municipal court system serves as the city's judicial branch. The city council and mayor promote ordinances to establish municipal policies. The Galveston City Council consists of six elected positions, each derived from a specified electoral district. Each city council member is elected to a two-year term, while the mayor is elected to a two-year term. The city council appoints the city manager, the city secretary, the city auditor, the city attorney, and the municipal judge. The city's Tax Collector is determined by the city council and is outsourced to Galveston County. The city manager hires employees, promotes development, presents and administers the budget, and implements city council policies. Joe Jaworski is mayor, having replaced term-limited Lyda Ann Thomas May 2010. Jaworski is also the grandson of Leon Jaworski, United States Special Prosecutor during the Watergate Scandal in the 1970s.[130]

City services

The Galveston Fire Department provides fire protection services through six fire stations and 17 pieces of apparatus.[131] The Galveston Police Department has provided the city's police protection for more than 165 years. Over 170 authorized officers serve in three divisions.

The city is served by the Rosenberg Library, successor to the Galveston Mercantile Library, which was founded in 1871. It is the oldest public library in the State of Texas.[132][133] The library also serves as headquarters of the Galveston County Library System, and its librarian also functions as the Galveston County Librarian.[134]

County, state, and federal government

Galveston is the seat and second-largest city (after League City, Texas) of Galveston County in population.[135] The Galveston County Justice Center, which houses all the county's judicial functions as well as jail, is located on 59th street. The Galveston County Administrative Courthouse, the seat of civil and administrative functions, is located near the city's downtown.[136] Galveston is within the County Precinct 1; as of 2008 Patrick Doyle serves as the Commissioner of Precinct 1.[137] The Galveston County Sheriff's Office operates its law enforcement headquarters and jail from the Justice Center.[138][139] The Galveston County Department of Parks and Senior Services operates the Galveston Community Center.[140] Galveston is located in District 23 of the Texas House of Representatives. As of 2008, Craig Eiland represents the district.[141] Most of Galveston is within District 17 of the Texas Senate; as of 2008 Joan Huffman represents the district.[142] A portion of Galveston is within District 11 of the Texas Senate; as of 2008 Mike Jackson represents the district.[143] Galveston is in Texas's 14th congressional district and is represented by Republican Randy Weber as of 2012.

The Galveston Division of the United States District Court for the Southern District of Texas, the first federal court in Texas, is based in Galveston and has jurisdiction over the counties of Galveston, Brazoria, Chambers and Matagorda.[144] It is housed in the United States Post Office, Customs House and Court House federal building in downtown Galveston.[145] The United States Postal Service operates several post offices in Galveston, including the Galveston Main Post Office and the Bob Lyons Post Office Station.[146][147] In addition the post office has a contract postal unit at the Medical Branch Unit on the campus of the University of Texas Medical Branch and the West Galveston Contract Postal Unit, located on the west end of Galveston Island in the beachside community of Jamaica Beach.

Transportation

Scholes International Airport at Galveston (IATA: GLS, ICAO: KGLS) is a two-runway airport in Galveston; the airport is primarily used for general aviation, offshore energy transportation, and some limited military operations. The nearest commercial airline service for the city is operated out of Houston through William P. Hobby Airport and George Bush Intercontinental Airport. The University of Texas Medical Branch has two heliports, one for Ewing Hall and one for its emergency room.

The Galveston Railway, originally established and named in 1854 as the Galveston Wharf and Cotton Press Company, is a Class III terminal switching railroad that primarily serves the transportation of cargo to and from the Port of Galveston. The railway operates 32 miles (51 km) of yard track at Galveston, over a 50-acre (200,000 m2) facility.[148] Island Transit, which operates the Galveston Island Trolley manages the city's public transportation services. Intercity bus service to Galveston was previously operated by Kerrville Bus Company; following the company's acquisition by Coach USA, service was operated by Megabus. All regular intercity bus service has been discontinued.

Galveston is served by Amtrak's Texas Eagle via connecting bus service at Longview, Texas.

Interstate 45 has a southern terminus in Galveston and serves as a main artery to Galveston from mainland Galveston County and Houston. Farm to Market Road 3005 (locally called Seawall Boulevard) connects Galveston to Brazoria County via the San Luis Pass-Vacek Toll Bridge. State Highway 87, known locally as Broadway Street, connects the island to the Bolivar Peninsula via the Bolivar Ferry. A project to construct the proposed Bolivar Bridge to link Galveston to Bolivar Peninsula was cancelled in 2007.[149]

Education

Colleges and universities

Established in 1891 with one building and fewer than 50 students, today the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) campus has grown to more than 70 buildings and an enrollment of more than 2,500 students.[150] The 84-acre (340,000 m2) campus includes schools of medicine, nursing, allied health professions, and a graduate school of biomedical sciences, as well as three institutes for advanced studies & medical humanities, a major medical library, seven hospitals, a network of clinics that provide a full range of primary and specialized medical care, and numerous research facilities.[151]

Galveston is home to two post-secondary institutions offering traditional degrees in higher education. Galveston College, a junior college that opened in 1967, and Texas A&M University at Galveston, an ocean-oriented branch campus of Texas A&M University.[152]

Primary and secondary schools

The city of Galveston is served by Galveston Independent School District, which includes six elementary schools, two middle schools and one high school, Ball High School. There is also one magnet middle school, Austin Middle School, serving grades 5 through 8.[153]

Galveston has several state-funded charter schools not affiliated with local school districts, including kindergarten through 8th grade Ambassadors Preparatory Academy and pre-kindergarten through 8th Grade Odyssey Academy.[154] In addition KIPP: the Knowledge Is Power Program opened KIPP Coastal Village in Galveston under the auspices of GISD.[155]

Several private schools exist in Galveston. The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston operates two Roman Catholic private schools, including Holy Family Catholic School (K through 8th)[156] and O'Connell College Preparatory School (9-12).[154] Other private schools include Satori Elementary School, Trinity Episcopal School, Seaside Christian Academy, and Heritage Christian Academy.[154]

Galveston Independent School District Administration Building

Galveston Independent School District Administration Building

Galveston in media and literature

- "Galveston" is the name of a popular song written by Jimmy Webb and sung by Glen Campbell.

- Sheldon Cooper, one of the main characters from the TV series The Big Bang Theory, grew up in Galveston.

- The theater film, The Man from Galveston (1963), was the original pilot episode of the proposed NBC western television series Temple Houston, with Jeffrey Hunter cast as Temple Lea Houston, a lawyer and the youngest son of the legendary Sam Houston. For a time the real Temple Houston was the county attorney of Brazoria County, Texas. The Temple Houston series lasted for only twenty-six episodes in the 1963-1964 television season.[157]

- Donald Barthelme's 1974 short story "I bought a little city" is about an unnamed man who invests his fortune in buying Galveston, only to sell it thereafter.[158]

- Galveston is the setting of Sean Stewart's 2000 fantasy novel Galveston, in which a Flood of Magic takes over the island city, resulting in strange and carnivalesque adventures. It tied in 2001 with Declare, by Tim Powers, for the World Fantasy Award for Best Novel. It also won the 2001 Sunburst Award and was a preliminary nominee for the Nebula Award for Best Novel.

- The Drowning House, a novel by Elizabeth Black (2013), is an exploration of the island of Galveston, Texas, and the intertwined histories of two families who reside there.[159]

- Stephenie Meyer has mentioned Galveston island in her third book of the Twilight series, Eclipse.

- Galveston (2010) is the first novel by Nic Pizzolatto, the creator of the HBO series True Detective.

Sister cities

Galveston has five sister cities, as designated by Sister Cities International:[160]

Armavir, Armenia

Armavir, Armenia Thiruvananthapuram, India

Thiruvananthapuram, India Veracruz, Mexico

Veracruz, Mexico Stavanger, Norway

Stavanger, Norway Niigata, Japan

Niigata, Japan

See also

Notes

- ↑ "History of the Oleander in America... By Way of Galveston". International Oleander Society. Retrieved 2009-10-09.

- 1 2 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ Donald E. Chipman (2008-01-18). "The Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association". www.tshaonline.org. pp. article "MALHADO ISLAND". Retrieved 2008-09-30.

- 1 2 David G. McComb. Table of Contents and Excerpt, McComb, Galveston. Galveston, A History - University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-72053-4. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- 1 2 Harris Gaylord Warren. "Aury, Louis Michel". Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- 1 2 3 Harris Gaylord Warren. "Lafitte, Jean". Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ↑ Jimmie Walker. "The Legend of Jean Lafitte". Kemah Historical Society. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- 1 2 "Port of Galveston". World Port Source. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ↑ "Menard, Michel Branamour". Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ↑ "The Galveston Collection". Texas Archival Resources Online, University of Houston. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- 1 2 3 4 "History of Galveston". Isaac's Storm, Random House. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ↑ "Galveston Island". Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ↑ "Galveston, Texas", Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities

- 1 2 Barrington, Carol; Kearney, Sydney (2006). Day Trips from Houston: Getaway Ideas for the Local Traveler. Globe Pequot. p. 241. ISBN 0-7627-3867-7.

- ↑ Alwyn Barr. "Galveston, Battle of". Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ↑ Hales, Douglas (2003). A Southern Family in White & Black: The Cuneys of Texas. Texas A&M University Press. pp. 18–19. ISBN 1-58544-200-3.

- ↑ "History: Galveston's Colorful Past". Galveston Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ↑ "The History of Galveston". Wyndham Hotels. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ↑ Hales (2003), Southern Family in White and Black, p. 15

- ↑ US 1870 Census

- ↑ Pitre, Merline. Cuney, Norris Wright. Handbook of Texas. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 15 October 2009.

- ↑ Obadele-Starks, Ernest (2001). Black Unionism in the Industrial South. Texas A&M University Press. pp. 39–44. ISBN 0-89096-912-4.

- ↑ Hales, Douglas (2003). A Southern Family in White & Black: The Cuneys of Texas. Texas A&M University Press. pp. 15–16. ISBN 1-58544-200-3.

- ↑ Edward Coyle Sealy. "Galveston Wharves". Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2009-09-13.

- ↑ "GULF COAST REGION: GALVESTON TEXAS". durangotexas.com. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 John Edward Weems. "Galveston Hurricane of 1900". Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ↑ Joe Strupp (2000-09-04). "Nation's deadliest natural disaster". Editor & Publisher. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ↑ "Handbook of Texas Online, s.v. "Commission Form of City Government,"". Retrieved 2009-10-15.

- ↑ "Galveston Movement". Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ↑ Hardwick (2002), p. 13

- ↑ Gary Cartwright (1998). Galveston: A History of the Island. TCU Press. ISBN 0-689-11991-7.

- ↑ "Annual Financials report, 2004-2005" (PDF). The Moody Foundation. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ↑ "American National Announces Fourth Quarter 2007 Results" (PDF). American National Insurance Company. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 1, 2011. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ↑ "Galveston Hotel - Hotel Galvez to Reopen October 15". Bloomberg.com. 2008-10-08. Retrieved 2009-09-26.

- ↑ "Preserve America Community: Galveston, Texas". Retrieved 2009-09-26.

- 1 2 David G. McComb. "Galveston, TX". Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2009-09-26.

- ↑ John Nova Lomax (2009-03-03). "Is Casino Gambling in the Cards for Galveston?". Houston Press. Retrieved 2009-09-26.

- ↑ "The Press: Gambling in Texas". Time Magazine. 1952-01-12. Retrieved 2009-09-26.

- ↑ Melosi, Martin V.; Pratt, Joseph A. (2007). Energy Metropolis: An Environmental History of Houston and the Gulf Coast. University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 0-8229-4335-2.

- ↑ Robert E. Baker. "Moody Foundation". Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ↑ Utley Robert Marshall (2007). Lone Star Lawmen. Oxford. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-19-515444-3.

- ↑ James G. Dickson, Jr. "Attorney General". Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2009-09-26.

"The Daily News: Headlines". The Galveston County Daily News. Retrieved 2009-09-26.

Sitton, Thad (2006). The Texas Sheriff: Lord of the County Line. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-8061-3471-0.

Communications, Emmis (December 1983). "Grande Dame of the Gulf". Texas Monthly: 169. - ↑ Melosi, Martin V.; Pratt, Joseph A. (2007). Energy Metropolis: An Environmental History of Houston and the Gulf Coast. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 202. ISBN 0-8229-4335-2.

- ↑ Paul Burka (1983-12-01). "Grande Dame of the Gulf". Texas Monthly. Retrieved 2009-09-27.

- ↑ Melosi, Martin V.; Pratt, Joseph A. (2007). Energy metropolis: an environmental history of Houston and the Gulf Coast. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 202. ISBN 0-8229-4335-2.

- ↑ "The History of Galveston College". Galveston College. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

Rhiannon Myers (2007-11-14). "Students brave the simulated seas". The Galveston County Daily News. Retrieved 2009-09-13. - ↑ Novak, Shonda Growth Wave Hits Galveston." Austin American-Statesman. Saturday July 22, 2006.

- ↑ Harvey Rice (2007-02-22). "Workers in Galveston increasingly can't afford to live there". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ↑ "Ike Insured Damage Estimates Range from $6B to $18B". Texas / South Central News, Insurance Journal. 2008-09-15. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ↑ "Galveston Still Healing 5 Years After Hurricane Ike". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- ↑ Jervis, Rick (2014-03-25). "After rebuilding from Hurricane Ike, Galveston deals with oil spill". USA TODAY. Retrieved 2015-09-25.

- ↑ "Rock Sediment and Soil Facts, Galveston Island". Geologic Wonders of Texas, University of Texas. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ↑ Woodhams, Susie. "After Ike, a deluge of reinvention." Boston Globe. June 5, 2011. Retrieved on June 6, 2011.

- ↑ D. Freeman. "Map 1. Galveston's Neighborhoods". Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ↑ Jones, Leigh. "Council to consider golf cart committee." Galveston County Daily News. November 9, 2009. Retrieved on June 11, 2012.

- ↑ Rice, Harvey. "Galveston Island gets tough advice from Rice study", Houston Chronicle, 26 October 2011, Retrieved on 24 October 2012

- 1 2 "Texas (TX), Galveston County". National Register of Historical Places. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ↑ "Silk Stocking National Historic District". Archived from the original on December 30, 2010. Retrieved 2009-04-15.

- ↑ "Weather Stats". Greater Houston Convention and Visitors Bureau. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- ↑ "Weather Stats". Greater Houston Convention and Visitors Bureau. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

Melosi (2007), p. 13 - ↑ "Monthly Averages for League City, TX (77573)". The Weather Channel. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ↑ "National Climatic Data Center]". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, United States Department of Commerce. 2004-06-23. Retrieved 2006-12-14.

- ↑ "Average Relative Humidity". Department of Meteorology at the University of Utah. Archived from the original on 2006-12-09. Retrieved 2006-12-14.

- ↑ "Monthly Averages for League City, TX (77573)". The Weather Channel web site. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ↑ "Monthly Averages for Pasadena, TX (77573)". The Weather Channel web site. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ↑ Berger, Eric (9 September 2008). "Would a category 3 hurricane surge flood your home?". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 2009-10-15.

- ↑ "Wide Ike and shallow coast mean strong surge". MSNBC. 12 September 2008. Retrieved 2009-10-15.

Houston is buffered by Galveston Island—which sits in the way of the surge—and the bay system

- ↑ Spinner, Kate (31 May 2009). "Hurricane forecasters zero in on threat of surge". Sarasota Herald Tribune. Retrieved 2009-10-15.

Just north of Galveston Island, the Bolivar Peninsula shields Galveston Bay much like Lido Key and Longboat Key shield Sarasota Bay.

- ↑ Official records for Galveston were kept at an unknown location from April 1871 to August 1946, at the COOP station from September 1946 to December 1996, and at Scholes Int'l since January 1997. The temperature record only dates back to June 1874. Therefore, precipitation day normals are not currently available at Scholes Int'l. For more information, see ThreadEx.

- 1 2 "NowData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 9, 2015.

- ↑ "WMO Climate Normals for Galveston, TX 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 9, 2015.

- ↑ "Monthly Averages for Galveston, TX". The Weather Channel. Retrieved 2012-02-08.

- ↑ Samenow, Jason (June 26, 2012). "Record setting heat wave roasts Rockies (Denver), Plains, heading east". The Washington Post.

- ↑ "Station Name: TX GALVESTON". National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2016-07-07.

- ↑ "US Census Press Releases". US Census Bureau. Retrieved 2009-10-14.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ "History of The Port of Galveston, Texas". The Post of Galveston. Archived from the original on 2009-10-21. Retrieved 2009-09-27.

- ↑ "6/23/10 - Galveston to Homeport Both Carnival Magic and Triumph". Retrieved 2010-06-27.

- ↑ "Life's a Trip: New Carnival megaship to call Galveston home". Retrieved 2010-06-27.

- ↑ Nell Newton. "American National Insurance Company". Hoover's. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ↑ "2008 Annual Report." American National Insurance Company. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ↑ "About Moody National Bank." Moody National Bank. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ↑ Laura Elder (2009-09-22). "After year in Webster, United Fire returns to isle". The Galveston County Daily News. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- 1 2 Harvey Rice (2009-09-16). "UTMB coming back stronger from Ike". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ↑ John DeLapp (2011-08-26). "UTMB gets OK to build new island hospital". The Daily News. Retrieved 2011-09-18.

- ↑ Scott Gonzales (2009-08-02). "UTMB emergency room reopens after Ike". The Galveston County Daily News.

- 1 2 Laura Elder (2009-07-07). "Shriners vote to keep isle burns hospital open". The Galveston County Daily News. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ↑ Elizabeth Allen (2009-07-10). "Shriners will keep hospitals open Galveston facility to reopen in a few weeks". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ↑ "Hospitals Listed by Specialty". Shriners Hospitals for Children. Archived from the original on 2009-08-26. Retrieved 2009-10-05.

- ↑ "A Gulf Coast gem is becoming a 'Playground of the South' all". meetingsfocus.com. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- ↑ "Galveston Island - Tour Texas". tourtexas.com. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- ↑ "Historic City, New Opportunities". Galveston Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved 2009-04-13.

- ↑ "Galveston Art Center". galvestonartscenter.org. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- ↑ http://www.guidrynews.com/08November/31908GAC.pdf

- ↑ "Galveston Art Center". galvestonartscenter.org. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- ↑ "About The Galveston Symphony Orchestra". The Galveston Symphony Orchestra. Retrieved 2009-04-13.

- ↑ "Galveston Ballet Home". Retrieved 2009-04-13.

- ↑ "Galveston Artist Residency". galvestonartistresidency.org. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- ↑ "National Hotel Artist Lofts". Artspace. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- ↑ "ES LEvy Home pg". mgaia.com. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- ↑ "The Proletariat". facebook.com. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- ↑ "National Trust for Historic Preservation Announces 2009 List of America's 11 Most Dangered Historic Places". Reuters. 2009-04-28. Archived from the original on January 22, 2010. Retrieved 2009-10-01.

- ↑ "Texas (TX), Galveston County". National Register of Historical Places. Retrieved 2009-10-01.

- ↑ "Galveston Grand 1894 Opera House". City of Houston eGovernment Center. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ↑ "Bishop's Palace--South and West Texas". A National Register of Historic Places Travel Itinerary, US National Park Service. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ↑ Carmack, Liz. Historic Hotels of Texas, Texas A&M University Press: College Station, Texas, 2007. pp. 47–49.

- ↑ "Ashton Villa--South and West Texas". A National Register of Historic Places Travel Itinerary, US National Park Service. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ↑ Judy D. Schiebel. "ASHTON VILLA". Texas State Historical Society: Handbook of Texas. Retrieved 2010-05-15.

- ↑ "Ashton Villa". National Park Service. Retrieved 2010-05-15.

- ↑ "1859 St. Joseph's Church". Galveston Historical Foundation. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ↑ "More About the 1861 Custom House". Galveston Historical Foundation. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ↑ "Galveston During the Civil War". Institute of Nautical Archaeology at Texas A&M University. Archived from the original on September 12, 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ↑ "The Galveston County Daily News". Galvestondailynews.com. Retrieved 2008-10-28.

- ↑ Leigh Jones (2009-03-10). "Island radio station making a comeback". The Galveston County Daily News. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- 1 2 "KHOU History". KHOU.com. Archived from the original on June 11, 2008. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ↑ Lomax, John Nova. "On Da Lingo, Part II." Houston Press. Thursday November 17, 2005. Retrieved on October 26, 2011.

- ↑ Merline Pitre. "Cuney, Norris Wright". The Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

- ↑ Baker, James Graham; Southwestern Historical Quarterly Vol CXIII; April, 2010

- ↑ "Vidor, King Wallis". The Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

- ↑ "Johnson, Jack". The Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

- ↑ Robert E. Baker. "Moody Foundation". The Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ↑ "Aviation". The Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

- ↑ "Tilman J. Fertitta". Forbes. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

- ↑ "Hutchison, Kathyrn Ann Bailey (Kay) – Biographical Information". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

- ↑ "Meet Gilbert Pena". Take Back House District 144. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ R. C. S. Trahair (2004). Encyclopedia of Cold War Espionage, Spies, and Secret Operations. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 267–268. ISBN 978-0-313-31955-6. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ↑ "MLB Player Stats (Matt Carpenter)". Retrieved August 23, 2013.

- ↑ Meyers, Rhiannon. "Jaworski replaces a tearful Thomas as mayor". Galveston Daily News. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- ↑ "Fire Department." City of Galveston. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ↑ "Rosenber Library". Handbook of Texas, Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- ↑ "Rosenberg Library". Rosenberg-library.org. Retrieved 2008-10-28.

- ↑ "About the Rosenberg Library." Rosenberg Library. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ↑ "Statistics, Galveston County". Bay Area Houston Economic Partnership. Archived from the original on June 17, 2008. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ↑ "Galveston County Justice Center." Galveston County, Texas. Accessed November 7, 2008.

- ↑ "Precinct 1." Galveston County, Texas. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ↑ "Welcome to the Galveston County Sheriff's Office Home Page." Galveston County Sheriff's Office. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ↑ "Galveston County Sheriff's Office Corrections Bureau - Jail Division." Galveston County Sheriff's Office. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ↑ Facilities Overview." Galveston County Department of Parks and Senior Services. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ↑ "District 23." Texas House of Representatives. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ↑ "Senate District 17" Map. Senate of Texas. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ↑ "Senate District 11" Map. Senate of Texas. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ↑ "Southern District of Texas, Galveston Division" (PDF). United States District and Bankruptcy Courts. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ↑ "Southern District of Texas, History of the District". United States District and Bankruptcy Courts. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ↑ "Post Office Location - Bob Lyons." United States Postal Service. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ↑ "Post Office Location - Galveston." United States Postal Service. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ↑ Nancy Beck Young. "Galveston Railway". Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ↑ Collette, Mark (July 8, 2007). "Bolivar bridge goes nowhere". The Daily News Galveston County. Retrieved 2013-06-12.

- ↑ Meghan Flynn (2009-08-01). "University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston: Stops for No Storm". Inside Healthcare. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011. Retrieved 2009-10-01.

- ↑ "Defining the Future of Health Care" (PDF). UTMB Office of Public Affairs. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 18, 2014. Retrieved 2009-10-01.

- ↑ "Texas A&M University, Galveston". Best Colleges - Education - US News and World Report. Retrieved 2009-10-01.

- ↑ Rhiannon Meyers (2008-02-06). "GISD hopes magnet school attracts students". The Galveston County Daily News. Retrieved 2009-10-01.

- 1 2 3 "Galveston, Texas Private Schools". galveston.com. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ↑ Radcliffe, Jennifer. "New KIPP campuses have younger focus." Houston Chronicle. March 30, 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ↑ Holy Family Parish Bulletin 02-14-2010

- ↑ Billy Hathorn, "Roy Bean, Temple Houston, Bill Longley, Ranald Mackenzie, Buffalo Bill, Jr., and the Texas Rangers: Depictions of West Texans in Series Television, 1955 to 1967", West Texas Historical Review, Vol. 89 (2013), pp. 106-109

- ↑ Barthelme's original story.

- ↑ Publisher

- ↑ "Galveston's Sister Cities". City of Galveston. Retrieved 2015-02-21.

References

- Larson, Erik. Isaac's Storm, New York: Vintage Books, 2000.

- Hardwick, Susan Wiley (2002). Mythic Galveston: reinventing America's third coast. JHU Press. p. 13. ISBN 0-8018-6887-4.7799766866800-08

External links

- Official City of Galveston website

- Galveston Island Convention and Visitors Bureau

- Galveston Chamber of Commerce

- Dr. J. O. Dyer, The Early History of Galveston, 1916, hosted by Portal to Texas History, University of Texas

- "History of Galveston", Isaac's Storm website, Random House

- "Bio of Isaac Monroe Cline", Isaac's Storm website, Random House

- Historical Galveston Architecture

.svg.png)