GNU

| |

|

Debian GNU/Hurd console startup and login | |

| Developer | Community |

|---|---|

| Written in | Various (notably C and assembly language) |

| OS family | Unix-like |

| Working state | Current |

| Source model | Free software |

| Marketing target | Personal computers, mobile devices, embedded devices, servers, mainframes, supercomputers |

| Platforms | IA-32 (with Hurd kernel only) and Alpha, ARC, ARM, AVR32, Blackfin, C6x, ETRAX CRIS, FR-V, H8/300, Hexagon, Itanium, M32R, m68k, META, Microblaze, MIPS, MN103, OpenRISC, PA-RISC, PowerPC, s390, S+core, SuperH, SPARC, TILE64, Unicore32, x86, Xtensa (with Linux-libre kernel only) |

| Kernel type | Microkernel (GNU Hurd) or Monolithic kernel (GNU Linux-libre, fork of Linux) |

| Userland | GNU |

| License | GNU GPL, GNU LGPL, GNU AGPL, GNU FDL, GNU FSDG[1][2] |

| Official website |

gnu |

GNU ![]() i/ɡnuː/[3][4] is an operating system[5][6][7]

and an extensive collection of computer software. GNU is composed wholly of free software,[8][9][10] most of which is licensed under GNU's own GPL.

i/ɡnuː/[3][4] is an operating system[5][6][7]

and an extensive collection of computer software. GNU is composed wholly of free software,[8][9][10] most of which is licensed under GNU's own GPL.

GNU is a recursive acronym for "GNU's Not Unix!",[8][11] chosen because GNU's design is Unix-like, but differs from Unix by being free software and containing no Unix code.[8][12][13] The GNU project includes an operating system kernel, GNU HURD, which was the original focus of the Free Software Foundation (FSF).[8][14][15][16] However, non-GNU kernels, most famously Linux, can also be used with GNU software; and since the kernel is the least mature part of GNU, this is how it is usually used.[17][18] The combination of GNU software and the Linux kernel is commonly known as Linux (or less frequently GNU/Linux; see GNU/Linux naming controversy).

With the April 30, 2015 release of the Debian GNU/HURD 2015 distro,[19][20] GNU OS now provides the components to assemble an operating system that users can install and use on a computer.[21][22][23] This includes the GNU Hurd kernel, that is currently in a pre-production state. The Hurd status page states that "it may not be ready for production use, as there are still some bugs and missing features. However, it should be a good base for further development and non-critical application usage."[21]

Due to Hurd not being ready for production use, in practice these operating systems are Linux distributions. They contain the Linux kernel, GNU components and software from many other free software projects. Looking at all program code contained in the Ubuntu Linux distribution in 2011, GNU encompassed 8% and the Linux kernel 9%.[24]

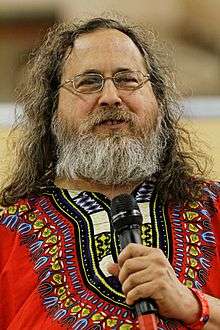

Richard Stallman, the founder of the project, views GNU as a "technical means to a social end" or in other words is a technical avenue to pursue social justice.[25] Relatedly Lawrence Lessig states in his introduction to the 2nd edition of Stallman's book Free Software, Free Society that in it Stallman has written about "the social aspects of software and how Free Software can create community and social justice."[26]

Development of the GNU operating system was initiated by Richard Stallman at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Artificial Intelligence Laboratory as a project called the GNU Project which was publicly announced on September 27, 1983, on the net.unix-wizards and net.usoft newsgroups by Richard Stallman.[27] Software development began on January 5, 1984, when Stallman quit his job at the Lab so that they could not claim ownership or interfere with distributing GNU components as free software.[28] Richard Stallman chose the name by using various plays on words, including the song The Gnu.[4](00:45:30)

The goal was to bring a wholly free software operating system into existence. Stallman wanted computer users to be "free", as most were in the 1960s and 1970s – free to study the source code of the software they use, free to share the software with other people, free to modify the behavior of the software, and free to publish their modified versions of the software. This philosophy was later published as the GNU Manifesto in March 1985.

Richard Stallman's experience with the Incompatible Timesharing System (ITS),[28] an early operating system written in assembly language that became obsolete due to discontinuation of PDP-10, the computer architecture for which ITS was written, led to a decision that a portable system was necessary.[4](00:40:52)[29] It was thus decided that the development would be started using C and Lisp as system programming languages,[30] and that GNU would be compatible with Unix.[31] At the time, Unix was already a popular proprietary operating system. The design of Unix was modular, so it could be reimplemented piece by piece.[29]

Much of the needed software had to be written from scratch, but existing compatible third-party free software components were also used such as the TeX typesetting system, the X Window System, and the Mach microkernel that forms the basis of the GNU Mach core of GNU Hurd (the official kernel of GNU).[32] With the exception of the aforementioned third-party components, most of GNU has been written by volunteers; some in their spare time, some paid by companies,[33] educational institutions, and other non-profit organizations. In October 1985, Stallman set up the Free Software Foundation (FSF). In the late 1980s and 1990s, the FSF hired software developers to write the software needed for GNU.[34][35]

As GNU gained prominence, interested businesses began contributing to development or selling GNU software and technical support. The most prominent and successful of these was Cygnus Solutions,[33] now part of Red Hat.[36]

Components

The system's basic components include the GNU Compiler Collection (GCC), the GNU C library (glibc), and GNU Core Utilities (coreutils),[8] but also the GNU Debugger (GDB), GNU Binary Utilities (binutils),[37] the GNU Bash shell[32][38] and the GNOME desktop environment.[39] GNU developers have contributed to Linux ports of GNU applications and utilities, which are now also widely used on other operating systems such as BSD variants, Solaris and OS X.[40]

Many GNU programs have been ported to other operating systems, including proprietary platforms such as Microsoft Windows[41] and OS X.[42] GNU programs have been shown to be more reliable than their proprietary Unix counterparts.[43]

As of November 2015, there are a total of 466 GNU packages (including decommissioned, 383 excluding) hosted on the official GNU development site.[44]

GNU variants

The official kernel of GNU Project was the GNU Hurd microkernel; however, as of 2012, the Linux kernel became officially part of the GNU Project in the form of Linux-libre, a variant of Linux with all proprietary components removed.[45]

Other kernels like the FreeBSD kernel also work together with GNU software to form a working operating system.[46] The FSF maintains that the Linux kernel, when used with GNU tools and utilities, should be considered a variant of GNU, and promotes the term GNU/Linux for such systems (leading to the GNU/Linux naming controversy).[47][48][49] The GNU Project has endorsed Linux distributions, such as gNewSense, Trisquel and Parabola GNU/Linux-libre.[50] Other GNU variants which do not use the Hurd as a kernel include Debian GNU/kFreeBSD and Debian GNU/NetBSD, bringing to fruition the early plan of GNU on a BSD kernel.

Copyright, GNU licenses, and stewardship

The GNU Project recommends that contributors assign the copyright for GNU packages to the Free Software Foundation,[51][52] though the Free Software Foundation considers it acceptable to release small changes to an existing project to the public domain.[53] However, this is not required; package maintainers may retain copyright to the GNU packages they maintain, though since only the copyright holder may enforce the license used (such as the GNU GPL), the copyright holder in this case enforces it rather than the Free Software Foundation.[54]

For the development of needed software, Stallman wrote a license called the GNU General Public License (first called Emacs General Public License), with the goal to guarantee users freedom to share and change free software.[55] Stallman wrote this license after his experience with James Gosling and a program called UniPress, over a controversy around software code use in the GNU Emacs program.[56][57] For most of the 80s, each GNU package had its own license: the Emacs General Public License, the GCC General Public License, etc. In 1989, FSF published a single license they could use for all their software, and which could be used by non-GNU projects: the GNU General Public License (GPL).[56][58]

This license is now used by most of GNU software, as well as a large number of free software programs that are not part of the GNU Project; it is also the most commonly used free software license.[59] It gives all recipients of a program the right to run, copy, modify and distribute it, while forbidding them from imposing further restrictions on any copies they distribute. This idea is often referred to as copyleft.[60]

In 1991, the GNU Lesser General Public License (LGPL), then known as the Library General Public License, was written for the GNU C Library to allow it to be linked with proprietary software.[61] 1991 also saw the release of version 2 of the GNU GPL. The GNU Free Documentation License (FDL), for documentation, followed in 2000.[62] The GPL and LGPL were revised to version 3 in 2007, adding clauses to protect users against hardware restrictions that prevent user to run modified software on their own devices.[63]

Besides GNU's own packages, the GNU Project's licenses are used by many unrelated projects, such as the Linux kernel, often used with GNU software. A minority of the software used by most of Linux distributions, such as the X Window System, is licensed under permissive free software licenses.

Logo

The logo for GNU is a gnu head. Originally drawn by Etienne Suvasa, a bolder and simpler version designed by Aurelio Heckert is now preferred.[64][65] It appears in GNU software and in printed and electronic documentation for the GNU Project, and is also used in Free Software Foundation materials.

The image shown here is a modified version of the official logo. It was created by the Free Software Foundation in September 2013 to commemorate the 30th anniversary of the GNU Project.[66]

See also

- Access to Knowledge movement

- Free culture movement

- Free software movement

- History of free and open-source software

References

- ↑ "GNU Licenses".

- ↑ "GNU FSDG".

- ↑ "What is GNU?". The GNU Operating System. Free Software Foundation. September 4, 2009. Retrieved October 9, 2009.

The name ‘GNU’ is a recursive acronym for ‘GNU's Not Unix‘; it is pronounced g-noo, as one syllable with no vowel sound between the g and the n.

- 1 2 3 Stallman, Richard (March 9, 2006). The Free Software Movement and the Future of Freedom. Zagreb, Croatia: FSF Europe. Retrieved February 20, 2007. Lay summary.

- ↑ Yi Peng; Fu Li; Ali Mili (January 2007). "Modeling the evolution of operating systems: An empirical study" (PDF). Journal of Systems and Software. Elsevier. 80 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2006.03.049. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 May 2009. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

...we have selected a set of fifteen operating systems: Unix, Solaris/Sun OS, BSD, Windows, MS-DOS, MAC OS, Linux, Net Ware, HP UX, GNU Hurd, IBM Aix, Compaq/ DEC VMS, OS/2.

- ↑ M. R. M. Torres; Federico Barrero; M. Perales; S. L. Toral (June 2011). "Analysis of the Core Team Role in Open Source Communities" (PDF). Complex, Intelligent and Software Intensive Systems (CISIS), 2011 International Conference on. IEEE Computer Society: 109–114. doi:10.1109/CISIS.2011.25. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

Debian port to Hurd...: The GNU Hurd is a totally new operating system being put together by the GNU group.

- ↑ Neal H. Walfield; Marcus Brinkmann (4 July 2007). "A critique of the GNU hurd multi-server operating system" (PDF). ACM SIGOPS Operating Systems Review. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. 41 (4): 30–39. doi:10.1145/1278901.1278907. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 November 2015. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 St. Amant, Kirk; Still, Brian. Handbook of Research on Open Source Software: Technological, Economic, and Social Perspectives. ISBN 1-59140999-3.

- ↑ "GNU Manifesto". GNU project. FSF. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ Raymond, Eric (2001-02-01). The Cathedral & the Bazaar: Musings on Linux and Open Source by an Accidental Revolutionary. pp. 10–12. ISBN 978-0-59600108-7.

- ↑ "GNU's Not Unix". The free dictionary. Retrieved 2012-09-22.

- ↑ "The GNU Operating system". GNU project. FSF. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

- ↑ Marshall, Rosalie (2008-11-17). "Q&A: Richard Stallman, founder of the GNU Project and the Free Software Foundation". AU: PC & Tech Authority. Retrieved 2012-09-22.

- ↑ Vaughan-Nichols, Steven J. "Opinion: The top 10 operating system stinkers", Computerworld, April 9, 2009: "…after more than 25 years in development, GNU remains incomplete: its kernel, Hurd, has never really made it out of the starting blocks. […] Almost no one has actually been able to use the OS; it's really more a set of ideas than an operating system."

- ↑ Hillesley, Richard (June 30, 2010), "GNU HURD: Altered visions and lost promise", The H (online ed.), p. 3,

Nearly twenty years later the HURD has still to reach maturity, and has never achieved production quality. […] Some of us are still wishing and hoping for the real deal, a GNU operating system with a GNU kernel.

- ↑ Lessig, Lawrence. The Future of Ideas: The Fate of the Commons in a Connected World, p. 54. Random House, 2001. ISBN 978-0-375-50578-2. About Stallman: "He had mixed all of the ingredients needed for an operating system to function, but he was missing the core."

- ↑ "1.2 What is Linux?", Debian open book, O'Reilly, 1991-10-05, retrieved 2012-09-22

- ↑ "What is GNU/Linux?", Ubuntu Installation Guide, Ubuntu (12.4 ed.), Canonical, retrieved 2015-06-22

- ↑ "Debian GNU/Hurd 2015 Released - Phoronix". www.phoronix.com. Retrieved 2016-03-24.

- ↑ "Debian GNU/Hurd 2015 released!". lists.debian.org. Retrieved 2016-03-24.

- 1 2 "status". www.gnu.org. Retrieved 2016-03-24.

- ↑ "Debian -- Debian GNU/Hurd". www.debian.org. Retrieved 2016-03-24.

- ↑ "Debian -- Debian GNU/Hurd — Configuration". www.debian.org. Retrieved 2016-03-24.

- ↑ Pedro Côrte-Real: How much GNU is there in GNU/Linux?

- ↑ Stallman, Richard (1986), "KTH", Philosophy (speech), GNU, Stockholm, Sweden: FSF.

- ↑ "ISBN 9781441436856 - Free Software, Free Society: Selected Essays Of Richard M. Stallman - OPENISBN Project:Download Book Data". www.openisbn.com. Retrieved 2016-03-24.

- ↑ Stallman, Richard (September 27, 1983). "new UNIX implementation". Newsgroup: net.unix-wizards. Usenet: 771@mit-eddie.UUCP. Retrieved August 18, 2008.

- 1 2 Holmevik, Jan Rune; Bogost, Ian; Ulmer, Gregory (March 2012). Inter/vention: Free Play in the Age of Electracy. MIT Press. pp. 69–71. ISBN 978-0-262-01705-3.

- 1 2 DiBona, Chris; Stone, Mark; Cooper, Danese (October 2005). Open Sources 2.0: The Continuing Evolution. pp. 38–40. ISBN 9780596008024.

- ↑ "Timeline of GNU/Linux and Unix".

Both C and Lisp will be available as system programming languages.

- ↑ Seebach, Peter (November 2008). Beginning Portable Shell Scripting: From Novice to Professional (Expert's Voice in Open Source). pp. 177–178. ISBN 9781430210436.

- 1 2 Kerrisk, Michael (October 2010). The Linux Programming Interface: A Linux and UNIX System Programming Handbook. pp. 5–6. ISBN 9781593272203.

- 1 2 Open Sources: Voices from the Open Source Revolution. O'Reilly & Associates, Inc. January 1999. ISBN 1-56592-582-3.

- ↑ Buxmann, Peter; Diefenbach, Heiner; Hess, Thomas (2012-09-30). The Software Industry. pp. 187–196. ISBN 9783642315091.

- ↑ Practical UNIX and Internet Security, 3rd Edition. O'Reilly & Associates, Inc. February 2003. p. 18. ISBN 9781449310127.

- ↑ Stephen Shankland (15 November 1999). "Red Hat buys software firm, shuffles CEO". CNET. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- ↑ "GCC & GNU Toolchains - AMD". Developer.amd.com. Archived from the original on 2015-03-16. Retrieved 2015-09-02.

- ↑ Matthew, Neil; Stones, Richard (2011-04-22). "The GNU Project and the Free Software Foundation". Beginning Linux Programming. ISBN 9781118058619.

- ↑ Sowe, Sulayman K; Stamelos, Ioannis G; Samoladas, Ioannis M (May 2007). Emerging Free and Open Source Software Practices. pp. 262–264. ISBN 9781599042107.

- ↑ "Linux: History and Introduction". Buzzle.com. 1991-08-25. Retrieved 2012-09-22.

- ↑ McCune, Mike (December 2000). Integrating Linux and Windows. p. 30. ISBN 9780130306708.

- ↑ Sobell, Mark G; Seebach, Peter (2005). A Practical Guide To Unix For Mac Os X Users. p. 4. ISBN 9780131863330.

- ↑ Fuzz Revisited: A Re-examination of the Reliability of UNIX Utilities and Services - October 1995 - Computer Sciences Department,University of Wisconsin

- ↑ "Software - GNU Project - Free Software Foundation". Free Software Foundation, Inc. 2016-01-13. Retrieved 2016-01-13.

- ↑ "GNU Linux-libre". 2012-12-17. Retrieved 2013-02-09.

- ↑ Kavanagh, Paul (2004-07-26). Open Source Software: Implementation and Management. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-55558320-0.

- ↑ Welsh, Matt (8 September 1994). "Linux is a GNU system and the DWARF support". Newsgroup: comp.os.linux.misc. Retrieved 3 February 2008.

RMS's idea (which I have heard first-hand) is that Linux systems should be considered GNU systems with Linux as the kernel.

- ↑ Proffitt, Brian (2012-07-12). "Debian GNU/Linux seeks alignment with Free Software Foundation". ITworld. Retrieved 2012-09-22.

- ↑ "1.1. Linux or GNU/Linux, that is the question". SAG. TLDP. Retrieved 2012-09-22.

- ↑ "List of Free GNU/Linux Distributions", GNU Project, Free Software Foundation (FSF).

- ↑ "Copyright Papers". Information For Maintainers of GNU Software. FSF. 2011-06-30. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ "Why the FSF gets copyright assignments from contributors". GNU. FSF. 2011-07-15. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ "How to choose a license for your own work". GNU. Free Software Foundation. Retrieved 2012-07-12.

- ↑ Raymond, Eric S (2002-11-09). "Licensing HOWTO". CatB. Retrieved 2012-09-22.

- ↑ "GPL 1.0", Old licenses, GNU, FSF.

- 1 2 Kelty, Christopher M (June 2008). "Writing Copyright Licenses". Two Bits: The Cultural Significance of Free Software. ISBN 978-0-82234264-9.

- ↑ The History of the GNU General Public License, Free Software.

- ↑ "GNU's flashes", GNU's Bulletin, GNU Project, Free Software Foundation (FSF), 1 (5), Jun 11, 1998.

- ↑ "Open Source License Data". Open Source Resource Center. Black Duck Software. Retrieved September 24, 2012.

- ↑ Chopra, Samir; Dexter, Scott (August 2007). Decoding Liberation: The Promise of Free and Open Source Software. pp. 46–52. ISBN 978-0-41597893-4.

- ↑ The origins of Linux and the LGPL, Free BSD.

- ↑ Goldman, Ron; Gabriel, Richard P (April 2005). Innovation Happens Elsewhere: Open Source as Business Strategy. pp. 133–34. ISBN 978-1-55860889-4.

- ↑ Smith, Roderick W (2012). "Free Software and the GPL". Linux Essentials. ISBN 978-1-11819739-4.

- ↑ "A GNU Head". Free Software Foundation (FSF). 2011-07-13. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ "A Bold GNU Head". Free Software Foundation. 2011-07-13. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ "GNU 30th Anniversary". Free Software Foundation. 2013-10-08. Retrieved 2014-12-15.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to GNU. |